The Smiths

Smith & Wessons were famed for their trigger pulls. The thing that made their double action pulls so smooth and consistent was the flat spring that powered the hammer.

The only Smiths built with a coil hammer spring, that I’m aware of, were the J-frames (see Appendix II for an example of a customized, post-production exception to that rule).

Smith & Wesson Frames

Smith & Wesson made different sized frames. As with cars, several variants were built upon the same chassis. From smallest to largest, those chassis or frames were:

- J-frame: the small snubbies, such as the Model 36 Chief’s Special.

- K-frame: mid-sized, like the Model 10, the most common police revolver of the 20th century.

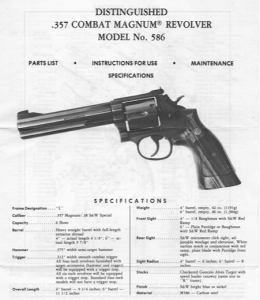

- L-frame: Like a luxury sedan, the Models 586 and 686. Slightly larger around the cylinder than the K-frames, L-frames had grips identical to K-frames.

- N-frame: Smith’s biggest revolvers, capable of handling the .44 mag, .41 mag, and .45 long Colt. Smith’s M1917 of WWI was built in an N-frame. The .357 was developed in N-frames, because the higher pressures would not blow one up.

The grip portion of Smith & Wesson frames came in two basic shapes: square butt and round butt (see below).

Part I

The Scepter of an Officer

Beast

In the summer of 1981, when I went through BCT (Basic Cadet Training, or “Beast”) in Jack’s Valley at the Air Force Academy in Colorado, we qualified on the USAF’s Smith & Wesson Model 15 .38 revolver.

The Model 15 Smith was the standard sidearm of an Air Force officer during the 1960s, ’70s, and most of the ’80s.

“Standard” may not be the correct term, as on any given day, only a fraction of the USAF personnel carried a sidearm.

Handgun – Armed AF Personnel in the 1980s

Security Police were armed 24 / 7 / 365.25, of course. Officers carried sidearms as a general rule; some chose to carry a “shorty” GAU or GUU (predecessor of the M4 carbine) as well. M60 machine gunners sometimes carried a sidearm. Law enforcement specialists, a much smaller subset of the SP career field, carried wheel guns until the M9 came along (see Part III below).

AF OSI Special Agents had carried handguns, including snubbie revolvers, since the agency’s inception. In the 1980s they carried a chopped down GI .45 (see The GI .45: A Classic Single Action Only). Although a friend and classmate’s first job after graduation was as an AF OSI SA, and I wound up spending 2 decades as a federal criminal investigator, such a career was not even on my radar when I went through Beast. Since I went over to the Dark Side, I’ve run into Service Academy grads and other fighter pilots’ brats who wound up in the FBI and the USMS and HSI.

Missile combat crews (MCCs) carried revolvers, 24 / 7 / 365.25, to secure their nuclear ICBM control facilities. This changed in the late ’80s or early ’90s. Spoiler: after they were locked in their capsules for their 24 hour shifts, they took off those fancy MCC “crew blues” jumpsuits you saw in the movie WarGames, and put on sweats or jeans. They buckled their web belts and sidearms on over their sweatpants.

Certain USAF couriers and command post personnel carried sidearms in peacetime.

SAC alert bomber crews did, for at least part of the Cold War. We may assume that on airborne alert missions such as Chrome Dome, where nuclear armed aircraft were constantly in flight, ready to attack the Soviet Union from 1960 to 1968, the crews carried sidearms in addition to hydrogen bombs. Strategic Air Command (SAC) was deadly serious about their biz. When Curt LeMay was in charge, SAC bomber crews even trained on knife fighting.

By the 1980s, though, SAC bomber crews weren’t regularly armed, at least not in the mole holes where they sat on alert, waiting for the launch orders. Col Mario C, a retired Cold Warrior who taught firearms with me at Ft Bliss, wrote:

“I started sitting alert in the BUFF [B-52: Big Ugly Fat, uh, Fellah] in 1984. We didn’t have any weapons on day-to-day alert with us but understood that they might be given to us if tensions heightened . . . I do remember that the Officer in Charge at the Wing command post carried a snub nose. Anyways, you can’t trust those crew dogs with guns.

“I started sitting alert in the BUFF [B-52: Big Ugly Fat, uh, Fellah] in 1984. We didn’t have any weapons on day-to-day alert with us but understood that they might be given to us if tensions heightened . . . I do remember that the Officer in Charge at the Wing command post carried a snub nose. Anyways, you can’t trust those crew dogs with guns.

Interestingly, I did get to carry a snub nose revolver once for an alert generation exercise. When we brought up a bomber for alert status, we had to escort the sealed CMF (Combat Mission Folder) box that contained our mission profile and the “tickets” that launched us. At least one crew member had to be “armed” when carrying the box to the jet and two crewmembers had to be near the box at all times. Being the youngest member on the crew at the time I found out why my crew sent me to get the weapon. When I went to the armory to check out the snubbie, I signed for, and was issued the weapon, a shoulder holster, and a sealed bag of six bullets. I was told that I was not to load the weapon and I was to carry the bullets in my flight suit pocket . . . of course my first thought was why was I carrying this thing if I couldn’t even load it. My second thought was of Barney Fife. Hence the reason my crew got a laugh out of me having to carry an unloaded weapon with bullets in my pocket.”

It should be noted that while the USAF has explicit instructions regarding how each “ground weapon” is to be loaded, commanders often take it upon themselves to institute more restrictive rules. Some of these involve the absolute requirement to prevent discharges on aircraft in flight, but most are due to the commander’s own ignorance of small arms handling. Commanders’ fear of a career limiting “Aw, sh–!” by their insufficiently trained troops exceeds their fear that those troops will be killed by enemy action. Coalition Forces Land Component Commander (CFLCC, or “see flick”) rules prohibiting the chambering of ammunition in sidearms contributed to the deaths of several airmen in a gunfight in Kabul on 27 Apr 2011; see Dual Arming: Replacing the Bayonet with a Pistol towards the end of the Bayonets article for details. But, getting back to the 1980s,

Military Airlift Command (MAC) cargo crews operating in some areas were armed for anti-hijack purposes. If the plane was going to remain overnight at an insecure airfield, MAC usually brought along security troops to guard the plane while the crew was “resting” in a local hotel bar. MSgt James M was a security policeman at Travis AFB, a major west-coast MAC “hub” serving the Pacific, in 1985 -86. They carried Smith Model 15s in a shoulder holster when guarding C-5s overseas. Modern “Ravens” escorting Air Mobility Command aircraft are now dual armed with rifles and pistols.

Pilots flying combat missions carried a sidearm, although it was of limited utility if they were shot down. In the ’80s, Smiths (including Navy Victory Models) probably flew over Beirut, Panama, Grenada, and a few other undeclared and undisclosed locations.

Aircrew Sidearms in the Cold War

My goal in attending the AF Academy was to become a pilot, and indeed the vast majority of those who graduated in my age cohort (mid 1980s) did end up in pilot training.

Before Daesh made a habit of burning captured pilots alive, most aircrews considered surrender preferable to going down in a hail of gunfire, even though our POWs in North Vietnam had been tortured mercilessly. Many were tortured to death.

In the 1950s, my father had flown F-86s with Robinson Risner, one of the bravest men (among many brave men) I ever met, in the 50th Fighter Bomber Wing in Europe.

Colonel Risner described the pre-mission process for pilots in the Vietnam war:

“After a cup of coffee and a doughnut, we picked up our guns out of the gun locker. Most of us had .38 Combat Master Pieces.”

— (sic), The Passing of the Night, p. 7

Colonel Risner was shot down in an F-105 about 10 miles north of Thanh Hoa, North Vietnam. He was trying to get untangled from his chute, radio, and survival pack when he heard someone approaching from the other side of a rice paddy dike.

He drew his revolver and cocked it, but when he peered over the top of the levy, he was staring down the muzzle of a rifle. Risner’s sidearm was pointed up in the air at about 45 degrees, and he was being surrounded by other North Vietnamese. It’s doubtful he could even have taken a single enemy with him, much less escaped–so he dropped his revolver in the mud (Risner, The Passing of the Night, pp. 8 – 12).

Robbie spent seven and a half years in the Hanoi Hilton. Rodney Knutson also served as POW, but before he was captured, Rodney had to shoot back (see below).

Names of Different Smith Models

Smith & Wesson had previously designated its models with the frame size, the caliber, and a name. Even after they started using simple model numbers in 1957, the brand name (like Combat Masterpiece) stuck.

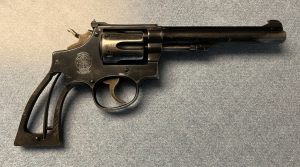

The Model 15 started out as the K-38 Combat Masterpiece. Meaning, a K-frame .38 Special, with particular features, such as a 4″ barrel and a ramped front sight (see below). A similar gun, offered with longer (6″ and 8 3/8″) barrels, and a squared-off Patridge front sight, was called the K-38 Target Masterpiece (later designated the Model 14).

If a Smith & Wesson was different from other Smiths in major ways, it got its own Model number. Once a Model was in production, minor changes in manufacturing methods or features earned the newer version of each Model a dash number (e.g., 15-2, 15-3, etc). See Model 15 Variants below for specifics of the Model 15 dash numbers.

USAF Handguns Before the Model 15

M1911A1

The USAF Air Police (“Apes”) had previously carried M1911A1 .45s (and / or M-1 carbines, depending on their posting). The M1911 and M1911A1 were commonly known as the “GI .45.” GI stood for “government issue.” Although Colt held the patent and made a civilian version called the Government Model, M1911A1s had also been made in WWII by Ithaca, Remington Rand, and even Singer Sewing Machine (the latter are quite rare). The M1911 series is one of the more copied and imitated pistol designs on the planet. I’m almost certain my father was issued an M1911A1 when he flew Mustangs in the Korean war.

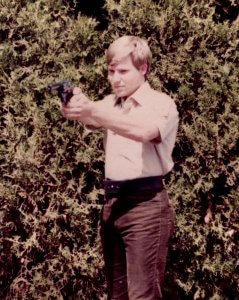

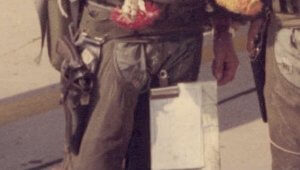

Dad and his crew chief, Corporal Matthews, by their Mustang, “The Loganberry Lancer,” FF-962, probably at Taegu AB, Korea. That looks like a GI .45 strapped to the 1Lt’s hip, with a double mag pouch on the left side.

D Flight, 45th Tac Recon Sqdn, by a F-51 Mustang. L to R, my father, Bill Zalinski, Herd Harding, Tom Rutherford, Jackie R. “Doug” Douglas. No sidearms in this hero shot.

Another shot from my dad’s Korean war photo album. Don Pickell (or Pickerell), center, clearly has a GI .45 (note lanyard loop on mainspring housing and empty mag well) in his shoulder holster, along with a double magazine pouch. No telling what Doug (left) has, but Petree on the right appears to have a GI .45. Note three different holster / belt combinations.

The 1911A1 was a heavy piece of shootin’ iron.

Colt and Smith M-13s

In the early 1950s, the Air Force requested a lightweight revolver with a 2″ barrel for aircrews. Colt produced one with an aluminum frame and barrel, which the USAF designated the M-13. Smith & Wesson produced a K-frame round butt, based on Smith’s Model 12. The aluminum cylindered Smith was, curiously, also designated M-13.

The aluminum M-13s had an unfortunate tendency to come apart when fired (see M41 in PGU-12/B below).

M-13s were only in service from about 1953 to 1959. I’ve read sources saying the AF adopted the Smith Model 15 in 1956, and others saying ’62, but I’m sure the USAF had a replacement handgun for aircrews when they retired the M-13s.

Suppressed High Standard

U-2 pilots flying secret high altitude reconnaissance missions on the edge of, and into, Soviet airspace in the late 1950s & early 1960s carried a High Standard .22 with a sound suppressor. According to U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers (and author Curt Gentry),

“The pistol was especially made by High Standard. It was a .22 caliber and had an extra long barrel with a silencer on the end. Although rated Expert in the service, I was out of practice and tested it periodically on the range. While the silencer obviously decreased the velocity, it was far more accurate than I had expected. Not completely silent, it was quiet enough that if you were to shoot a rabbit you could do so without alerting the whole neighborhood. Only .22 caliber, however, it wouldn’t be a very effective weapon of defense.” (Operation Overflight, p. 46)

Smith & Wesson Model 56 Snubbie

According to GunAuction.com, the Air Force procured 15,205 Model 56 revolvers in 1962 and 1963. The 56 was a K-frame .38 with a 2″ heavy barrel and adjustable sights. The thickness of the barrel seems to have been the major difference between a 2″ Model 56 and a 2″ Model 15. Some of the Model 56s may have been issued to OSI agents, although according to the snippet on GunAuction.com, they were procured for aircrews. I’ve never (that I remember) examined a Model 56, but according to descriptions on gun auction sites (56s are rare and command high prices) the back strap (metal part of the grip) of a Model 56 was smooth, except for the US marking. The back strap of a Model 15 had vertical grooves to grip your palm and keep it from twisting around in your hand.

USAF Adopts the Combat Masterpiece

Sources I’ve read say the Elite Guard at Strategic Air Command (SAC) headquarters, Offutt AFB Nebraska, were the first in the USAF to order the Smith & Wesson Model 15s. Before long, Model 15 Smiths were issued Air Force-wide for APs (renamed SPs, Security Police, in about 1966), missile combat crews, and aircrews.

Smith & Wesson Model 15s had the following features:

- Most if not all USAF Model 15s had a 4″ barrel. Starting in 1964, Smith also made a 2″ version of the Model 15 (see Variants below).

- A rib running down the top of the barrel. This rib was standard on thinner Smith barrels after 1946. The rib had grooves running down the length of its top to reduce glare as one visually acquired the sights. The thicker “bull” barrels also had a ribbed flat top, but it was like a squared-off part of the barrel. The rib on our Model 15s (and other thinner barreled Smiths) was like the top of a train’s rails; it had a T-shaped cross section.

- A rear sight adjustable for windage and elevation

- A ramped, “Baughman quick draw” front sight. The ramp was slightly harder to focus on than a squared off, Patridge type sight (not a problem when my eyes were younger), but ostensibly it would not scrape up a bunch of leather clearing a holster in a hurry.

Model 15 Variants

Below is a time-line of Smith & Wesson Model 15 production, with dash variants. Once a dash number change occurred, that feature or production method remained, even on subsequent dash numbers, unless otherwise noted.

- 1949: K-38 Combat Masterpiece (4″ only) introduced

- 1957: Name changed to Model 15 Combat Masterpiece

- 1959: Model 15-1, extractor / ejector rod changed to left hand thread. This kept it from unscrewing as the cylinder rotated (see below).

- 1961: Model 15-2, changed cylinder stop and trigger guard

- 1964: 2″ barreled Model 15-2 introduced

- 1967: Model 15-3, different rear sight adjusting screw

- 1977: Model 15-4, cylinder arm (crane) modified

- 1982: Model 15-5, trigger mechanism modified. Smith & Wesson stopped pinning the barrels of all its revolvers in 1982.

- 1986: 6″ and 8.5″ barreled versions of the Model 15-5 introduced

- 1988: Model 15-6, cylinder arm catch modified. In 1988, Smith stopped producing the 2″ and 8.5″ barreled Model 15s.

- 1992: Smith stopped producing 6″ Model 15-6s.

- 1994: Model 15-7, changes to ejector star and the rear sight.

- 2000: Model 15-7 production terminated.

The USAF had over 100,000 Smith Model 15s, but as of this writing I’m unaware of what years they were manufactured. USAF Security Forces used Model 15s to shoot blanks for K9 training into the 2020s, but I believe the Air Force stopped procuring them in the 1960s or ’70s, so the second half of the bulleted list above did not pertain to the Air Force. Information in the above timeline is mostly from A.E. Hartink’s Complete Encyclopedia of Pistols and Revolvers, pp. 301 – 302.

SAC Cold War veteran Colonel Mario C, who has researched the Model 15s, said that most of the Model 15s procured by the USAF were -3s. I did not record the dash numbers of the Model 15s I shot when I was a cadet at USAFA, but when I went back to USAFA’s Jack’s Valley range to shoot an Excellence in Competition match in 1986, the Smith I shot was a 15-2.

Why the Switch to Left Hand Thread?

The most significant change above was with the dash ones, which pre-dated most if not all USAF Smith & Wesson purchases.

In about 1959, Smith converted all their ejectors to a left hand thread. That may sound really esoteric, but if you know anything about the Smith revolvers and how to keep them running, you’ll realize how important that decision was. The switch was complicated and expensive and doing so across all production lines was not undertaken lightly by Smith’s management.

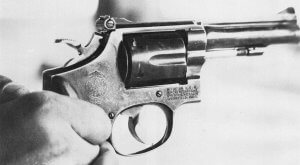

Smith & Wesson cylinders rotate counter clockwise, when viewed from the rear. The cartridge on the top right, from the shooter’s point of view, will be next behind the barrel when the hammer is cocked (either by the trigger or with your thumb). The ejector is the rod under the barrel. Pushing rearward on the ejector, when the cylinder crane is swung out of the frame, pushes on the star under the rims of the cartridge cases, pushing them out of the cylinder.

The ejector rod is screwed into the cylinder from the front. When the rod had a right hand thread, left hand rotation of the cylinder combined with any friction from the pin holding the front end of the rod in place essentially unscrewed it.

It is a popular misconception that revolvers do not “jam.” Wheel guns tend to jam less often than semi-autos, but when revolvers do get stuck they are very, VERY difficult to unstick. When that rod comes loose, the cylinder assembly (the whole train between the front pin under the barrel and the breech face in the back of the frame, which includes the ejector rod and the extractor star) gets longer than the space it fits into. The cylinder will become harder to turn (in double action mode, you’ll notice when the trigger gets really stiff) until eventually it locks up altogether.

Because the cylinder rotates counter-clockwise, when the rod is screwed in with a left hand thread, it comes loose less often and is easier to fix when it does. Holding the rod in place while rotating the cylinder can get you started.

In a fight, one would simply keep pulling through the trigger despite the increasing resistance.

If the cylinder locked up altogether, one would need to switch to empty hands, a secondary weapon such as a knife, or beat him with the revolver. If the bad guy was out of arms’ reach, you could press the right side of the cylinder against something hard that sticks out a little, like a door jamb, while simultaneously pushing forward on the Smith’s cylinder release (see Appendix I for cylinder releases of other manufacturers). Use your palm to push on the left side of the barrel AHEAD of the cylinder crane.

This method could bend a rod or tweak a crane out of alignment, but in a fight we would be less concerned about that than we would be about getting the gun running again, even poorly.

The rod working loose doesn’t happen all that often. The key is prevention: when you pick up a Smith & Wesson, do a little finger-tightness check on the ejector rod. The front end of the rod is checkered (knurled) just so you can do that.

A far more common culprit when revolvers jam is debris under the ejector star. Even a few flakes of unburned powder in there can, again, make the assembly longer than the tight tolerances of the hole in the frame it’s supposed to fit into. Before the fight, being meticulous about brushing out the area under the star is key. During a fight, vigorous, single stroke, downward ejection with your palm over the end of the ejector rod works better to keep the area under the star clear of unburned powder than multiple short strokes trying to get those empty cases out (the USAF trained us to use our left thumbs to push on the ejectors, but that does not generate sufficient stroke when cases are fire-formed to any grit in the chambers, and is less likely to keep unburned propellant from coming out of a case mouth and landing under the star).

The thumb method works most of the time. Most of the time is great on a range but not so much in a fight. Combat Arms (formerly SAMTU, Small Arms Marksmanship Training Unit) mainly taught us how to hit a distant target with small groups in slow fire. I picked up most of my “stress resistant, combat ready” revolver manipulation methods while working at a shooting range from 1984 – 1986 (see Part II below).

We cover those and other tips & tricks in our Lost Art of the Revolver courses.

Training and Qualification

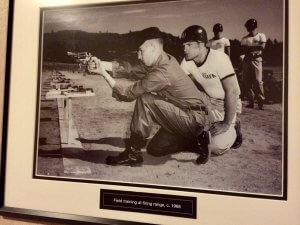

When I joined the AF, the qualification course, like most small arms training in those days, was mostly marksmanship oriented. Time limits were relatively generous. Most of the shooting took place at 25 yards.

The only “tactical” part of the qualification, if you will, was shooting from different positions like kneeling and prone.

I qualified on the first try, but I did NOT score “expert,” even though I had practiced with a friend’s Colt Police Positive revolver the previous spring, and again in the summer before I reported to BCT.

In September & October of 1982, determined to do better, I took an optional Pistol Marksmanship course offered as a USAF Academy PE elective. Our coach was Combat Arms Sgt Larry G. Hadley.

Our first four practice sessions were with Feinwerkbau Westinger & Altenburger .177 pellet (air) pistols, at 10 meters. Our next session was with a .22 target pistol at 50 feet. We went back to the pellet pistol one more session (again, at 10 meters) before graduating completely from the air pistols, moving on to the .22, and then, to the S&W Model 15.

As mentioned above, the AFQC (Air Force Qualifying Course) for the .38 revolver had us shooting from standing, kneeling, and even prone, around both sides and the top of barricades. But ONLY 5 OF THE 40 SHOTS WERE DOUBLE ACTION. The rest of the time it was thumb-cocked, relatively slow fire bullseye shooting.

Not surprisingly after all that basic marksmanship practice, I scored “expert” on a course that was mostly marksmanship oriented.

About that time, the USAF started giving us a ribbon just for passing basic training. I went through basic training twice (once when I enlisted in the reserves, and again a year later at the Air Force Academy), so I suppose I deserved at least one basic military training ribbon–especially since, for freshmen at service academies, basic essentially lasts for most if not all of the first year. But the first “dec” I really earned was the USAF marksmanship ribbon for pistol.

Rodney Knutson and the Smith Victory Model

When I was a third classman (sophomore) at USAFA, I went to a P-40 pilots convention with my father, who had flown Warhawks in WWII. The keynote speaker, Navy Capt Rodney Allen Knutson, was also the son of a Warhawk pilot, but he’d been born earlier, and had been shot down over North Vietnam. Then-Lieutenant (junior grade) Knutson was trying to surrender to an armed villager when a NVA (North Vietnamese Army soldier) ran over, butt-stroked the villager, and began shooting at Knutson.

The beleaguered Lt (jg) dropped to a knee and shot back with his issued .38.

Naval aviators carried WWII era Smith & Wesson “Victory Model” K-frames (essentially a Model 10 with a lanyard loop on the butt) through Korea, Vietnam, and even Desert Storm. Capt Knutson said he remembered wondering if he was violating the Geneva convention, as Navy pilots carried tracers in their .38s to signal search and rescue from a life raft.

Knutson killed the first NVA, but then was jumped from behind. He shot over his shoulder, killing a second NVA, but was simultaneously knocked out by the muzzle blast of that NVA’s rifle; a bullet fired point blank grazed his nose. Knutson woke up in captivity, and didn’t get home until 1973 (there’s far, far more to his fascinating story, which I’m saving for its own Personal Heroes post).

So even though I planned to do most of my combat shooting with a 20mm electric gatling gun from the cockpit of an F-15, and I knew that making a lot of noise is not generally advisable in Escape & Evasion situations, I learned early on, from one who had been there and done that, that you might be forced to use your issued sidearm. I took handgun skills very seriously.

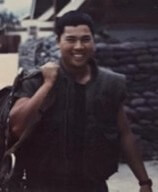

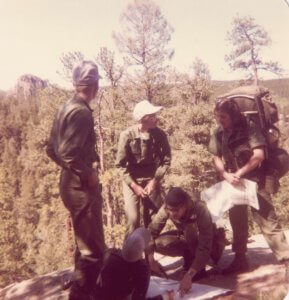

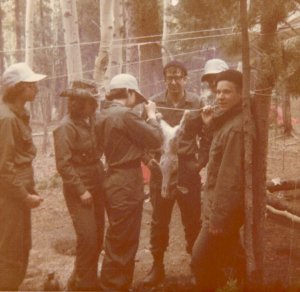

RECONDO / Tactical Leadership Decisions cadre

When I went through the Army’s Primary Non-Commissioned Officer (PNCOC, pronounced “pea-nock”) course, a program also called RECONDO (for RECOnnaissance CommaNDO, or Long Range Rifle Patrol) at Ft Carson in 1983, we trained on long guns and machine guns and LAW rockets and hand grenades and grenade launchers and ComBloc weapons.

But not handguns.

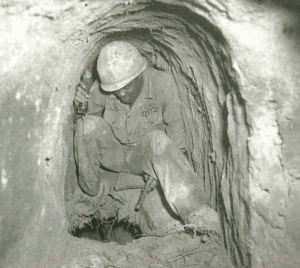

The notable absence of handgun training was not, I think, because we were officer candidates who were already familiar with issued handguns. Rather, pistols were specialty weapons in the Army. The platoon leader might hand one to the shortest, skinniest “tunnel rat” on the patrol before sending him in to clear a tight, dark enemy bunker with an angle-head flashlight.

But perhaps ironically, my Army training led to my first on-duty carry of a handgun outside of a firing range.

Graduating from Army PNCOC authorized us to become cadre on the USAFA Tactical Leadership Decisions (TLD) course.

When we got back to the Academy from Ft Carson that summer, we qualified on the USAF .38 again.

That time, we fired 55 rounds. 15 rounds were for sighting in, as the Model 15 had adjustable sights. If memory serves we shot at targets with oval, B-27 type scoring rings. I did not record the scoring scheme, nor how many were possible, but I’m guessing that 40 were for score, and that the X, 10, 9, and possibly the 8 rings counted as 5 points. Hits in the 7 (or 8?) ring counted as 4 points, and hits in the black outside those oval scoring rings added 2 points to the total. I did record that I scored 148 that time, 2 points shy of the 150 needed for an “expert” rating. I’m guessing the maximum possible was 200 points. 148 (or even 151) out of 200 is nothing to write home to mom about.

As TLD cadre, we needed to be qualified on the .38 because we took turns pulling armed CQ (charge of quarters), guarding the connex that held our M16s, blank ammunition, smoke grenades, trip flares, and other pyro.

I was a young man, and it was the first time that Uncle Sam entrusted me with the use of deadly force.

“Heavy” was a popular term in the vernacular of the day, immortalized by “Marty McFly” in Back to the Future. The heavy significance of that deadly force responsibility was not lost on me.

That Smith Model 15 was just a handgun, and not a very powerful one, at that. But its use or misuse could end the life of a human being. The signs outside the fence said “USE OF DEADLY FORCE AUTHORIZED” for a reason.

Our Air Force Academy instructors had told us that our job as military officers would be the selective and appropriate management of violence. Militaries primarily function by “killing people and breaking their stuff.” Our subordinates might be committing that violence, or we might be committing violence ourselves through the bomb sight of a jet, but our job as leaders was to make sure that the violence du jour was well executed and appropriate to the mission.

Which was all fine in theory, at some nebulous point in the future after we got our commissions, but there, hanging off my hip in Jack’s Valley, was a tangible steel instrument of violence.

It wasn’t so much the instrument itself. I had been shooting other people’s firearms since Boy Scout camp back in ’75. Many of my friends had guns (including AR-15s and M-1 carbines, well before the mass murder of strangers became a peacetime sickness) that were much “cooler” than a .38 revolver. But in my romantic, adolescent mind, when Uncle Sam told me to stand guard with that revolver, and ordered me to carry live ammo in it, it was like the Queen had ordered me to kneel and tapped me on the shoulder with a sword, bestowing upon me the authority to bear arms and mete justice.

When a new CQ took over, our standard practice was for the off going CQ to simply take off the web-belt, holster & all, and hand it to the oncoming CQ. I’m all for minimizing manipulations in the field, but after strapping on the belt, I insisted on pulling the Smith out of its holster, keeping it pointed down, and checking to make sure it was loaded with live ammo. It’s a habit that stays with me to this day. When I pull my EDC (every day carry) pistol from the safe, I check to make sure it’s properly loaded before putting it in my holster.

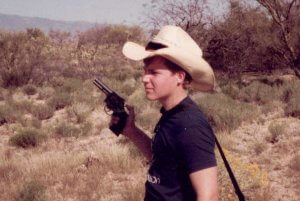

I flunked out of the USAF Academy halfway through my junior year, in January of 1984. I owed Uncle Sugar 2 years of enlisted time, but first I returned to Tucson as an inactive reservist on what they called an “educational delay,” to attend the University of Arizona.

I went to school during the day, and worked nights to pay the rent. Rent and food had not been student expenses at USAFA.

Part II

Private Security

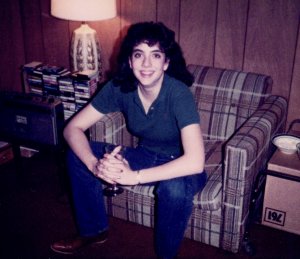

The Sarge: Smith & Wesson Model 586

The first civilian job I got after leaving the Blue Zoo was as a state-licensed, armed guard. I showed up for the interview at Ace Security on 01 Feb 1984 in a suit and tie. The other guy who interviewed at the same time looked like a homeless cowboy. We both got the job.

I paid the Arizona Department of Public Safety $7.50 for the employment license application and ID, and $12.00 for the fingerprints and background check.

Ace did give us some training. We were expected to carry a long, heavy flashlight over our support side shoulder, to block a blow, or strike back, or both, if we were suddenly attacked in the dark. I remember our instructor telling us to push doors all the way open, to make sure there’s nobody hiding behind, and to pause and look around before crossing the threshold. Those habits stay with me to this day.

“A door is like a bottle of fine wine. After it’s been opened, you should let it breathe for a bit.”

–Brad L, Marine, SWAT operator, special agent, and federal firearms / defensive tactics instructor

I applied at Ace because they were hiring, not for the uniforms, although Ace did pride themselves on having the most professional looking security guard duds in Tucson. They were wool, which wasn’t all that fun, even at night. Ace had a contract with a local dry cleaner so we would never show up to work looking like a bag of crushed you-know-whats. We wore neckties (ugh!).

Ace provided the uniforms, but I had to provide my own gun and duty gear. I purchased a 5-cell Maglite flashlight for $25.45, and a Bianchi Model 520 aluminum “Magic Wand” baton (redundant, since I carried the 5-cell flashlight) for $27, directly from Ace Security. They threw in a new flashlight holder and a used baton ring.

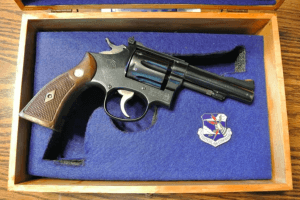

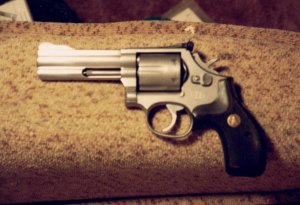

On 14 Feb 1984, I went to the only indoor firing range in town and bought a used, 4″ barreled, Smith & Wesson Model 586 .357 for $250, which came to $267.50 after tax.

I called that Smith Model 586 “the Sarge.”

I also bought a Bianchi 5BHL high-ride, thumb break holster for $47.62, to go on the used Sam Browne belt I already had. The Sarge was an L-frame, slightly larger than a K-frame. They didn’t have any holsters for L-frames; that Bianchi was made for a K-frame, but I used a straw to dab water into the holster in the tight spots (mostly where the full-length underbarrel lug was) and worked the Sarge in and out till it fit just right.

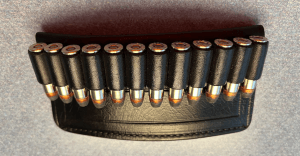

Ace let us carry speedloaders as well, and I did, but we were required to carry some of our spares in belt loops, not so much for “tac loads” (topping off a partially expended cylinder) as for show.

Security, after all, is all about deterrence. You’re not there to catch robbers. You’re there so the robbers will say “Let’s rip-off that other place down the street.”

Not everybody understood what a speedloader pouch was for, nor could the public see what was inside. But a rack of .357 cartridges in loops clearly said “I carry more than just the six in the gun.”

One accessed the rounds from belt loops (back when “access” was a noun, not a verb) by pushing them up from the bottom, rather than trying to claw at the rims with fingernails from the git-go. A true pistolero could pull and load two at a time.

I was working for Ace when I first noticed how bizarrely some people behave around authority figures–if you can call a 120 pound, 5’4,” 21 year old rent a cop in a wool suit an “authority figure.”

I was working at the Grant 5 drive-in theater. A pair of young ladies in a late model hatchback Firebird were causing a ruckus by playing their stereo too loud.

Who plays music while watching a movie? I thought, as I walked over there. Can’t remember if Footloose, Sudden Impact, or Blame it on Rio was on the big screen; there were 4 other screens too. The two ladies, one blonde and the other a brunette, had backed into the space, and were reclining in the back of the Pontiac with the hatch up, leaning against the back of the front seats.

The music was blasting so loud they could barely hear me. “Just, a sec, let me turn down the stereo,” the blonde one said, reaching over the front seat to flip the switch. I explained that the other people watching the movie wanted to hear the movie dialog through the little speaker boxes by their cars.

The darker haired gal was clearly the designated driver.

The blonde was very interested in my gear. She asked to see one of the shiny 145 grain aluminum jacketed Winchester Silvertip .357 cartridges I kept in those belt loops.

I didn’t see any harm in educating the public about what we carry, so I let her handle one. When it became obvious she was more interested in me than my gear, I told her I was flattered, but I already had a girlfriend.

My reluctance to fool around only seemed to encourage the blonde gal in the Pontiac. She was attractive and young and apparently not used to having to work for it. She came onto me like a hurricane. I’d never been a saint but I took relationships very seriously, so despite the fact that I was in immediate post adolescence, I managed to work up the will power to extract myself from her embrace as gently as I could.

I asked for my .357 cartridge back. She dropped it down her shirt and said I was welcome to go looking for it.

I let her keep it.

The vast majority of my security guard shifts were not nearly so interesting.

After I served for a few months as a night watchman at that drive-in, and at an air conditioning vent factory, and at construction sites, and escorted a lot of late evening cash drops, Wendy was perusing the want ads and found something that was right up my alley: I got a job at the same indoor shooting range where I’d bought the Sarge. I clerked evenings at that pistol range for the next two years.

Mortimer: Smith Model 65

Working at the range, I learned how to run a firing line, and a great deal about firearms safety–real safety, that works in the world outside a firing range–that I had not gotten from the USAF or the Army.

Apart from free range time, one of the perks of working there was paying wholesale for my shooting supplies. I showed Wendy how much I loved her by giving her a stainless steel K-frame Smith Model 65 round butt with a 3″ bull barrel and Pachmayr grips. She nicknamed it “Mortimer.”

The Smith Model 13 was essentially a Model 10 bored out to accept the longer .357 Magnum cartridge. The barrel was short–almost too short to burn most of that extra .357 gunpowder–but the extra thickness of the “bull” barrel made it relatively controllable. The Model 65 was simply a stainless steel version of the Model 13. Both had fixed sights.

Mortimer, like the Smith K-frame Models 13, 19, and 66, was capable of firing .357 Magnum. But K-frame operators were expected to most often shoot cheaper and lower recoiling .38 through them. Theoretically, one could break a K-frame shooting full power .357 Magnums through it all the time.

L-frames like the Sarge were slightly larger than the Ks, and capable of handling .357 Magnum on a regular basis.

.38 Special and .357 Magnum

The difference between .38 Special and .357 Mag? They shoot the same bullets; the case of the “Magnum” is just a little bit longer. Specifically, the .38 Special cartridge shoots a bullet slightly larger than 9mm out of a case 29 mm long. The .357 Magnum cartridge is virtually identical to a .38 Special, except that the case is 33 mm long, so it holds more powder, and was designed to reach higher pressures (with correspondingly higher velocity).

In short, .38 is shorter. You can shoot .38s in a .357, but not .357s in a .38.

Shrouded Ejectors and Barrel Lugs

The L-frame had a full length steel lug underneath the barrel, in front of the shrouded ejector. It was Smith’s answer to the elegant Colt Python, minus the Python’s signature vented rib barrel. With both of those pistols, the lug added weight forward, which helped to control recoil. It also looked cool.

“Plus, it has ‘the look,’ which is important.”

–Ian E, former Navy SEAL

Border Patrol legend was that Bill Jordan had requested the ejector of the K-frame S&W Model 19 be shrouded to prevent the ejector from being bent, should an agent need to whack anybody over the head with their revolver.

Most of the N-frames in those days had shrouded ejectors similar to the 19’s, shaped somewhat like the bow of a ship.

Grips

The grip portion of an L frame was identical to that of the K-frames.

The grips that came on the K-frames (and most other revolvers by every manufacturer) were hideously un-ergonomic. If you look at just about any auto pistol, you’ll see that the bottom of the trigger guard rests on the top of the middle finger. That places the trigger finger more or less in-line with the trigger.

But with DA / SA revolvers, the front strap of the grip comes up in a high, curving arc well above the trigger. If the middle finger is up in that gap, the index finger has to reach down and pull sideways, down toward the pinkie, rather than as God intended, toward the wrist and forearm.

The only reasonable explanation I’ve ever read for this–and I don’t know if it’s true–is that because most firing of DA / SA revolvers was single action, the high “sinus” or arched void between the grip and the trigger guard was there to reduce the distance between the middle finger and the thumb of one’s shooting hand, while rocking the revolver back to thumb cock it.

When I thumb cock a handgun–which isn’t often–I use my support side (left) thumb, so I can keep my dominant (right) hand grip where it should be, ready to fire.

In about May of 1986, at Camp Bullis, Texas, I was leading a patrol on an exercise. I wanted the troops to spread out a little. I looked left, made eye contact with the closest ones, and signaled the folks on the left with my left hand. Looking right, I held my slab-sided ’16 by the triangle handguard with my left hand, letting go of the pistol grip to signal to the folks on the right. “Always use your left hand to signal,” the SP Academy instructor who was shadowing me told me. “Never let go of that pistol grip with your shooting hand when contact is possible.” By contact, he meant with an enemy.

That sound advice stuck with me along countless trails along the Rio Grande, and when going through many doors serving warrants.

A company called “Tyler’s T-grips” came up with a solution of the arched sinus between the grip and the trigger guard of DA / SA revolvers: a small curving wedge to fill that gap, lowering the placement of the hand on the grip. The T-grip was held in place by two metal tabs that slipped under the grip panels.

The Sarge came with over-sized “Goncalo Alves,” wooden grip panels that filled in that gap. As a general rule, there were two drawbacks to oversized grips:

- Unless they had a divot cut out of the left side, they got in the way of speed loaders, and

- They worked best with oversized hands

Back when just about every cop in America carried a wheel gun, there were lots of companies who did nothing but make more ergonomic grips for revolvers. Some were made out of bone or antler, and others plastic, although most were wood, and some were quite elegant.

Some “target,” or bullseye, shooting grips were large and had a thumb rest on the left side for right handed shooters. Some were set up like that in reverse for lefties. But most of the custom wooden grips out there had the divot on the left side for speed loaders.

Companies like Pachmayr and later Hogue made a fortune producing ergonomic rubberized grips that absorbed some of the recoil. I got a set of Pachmayrs for the Sarge, since my tiny mitts had a hard time wrapping around the oversized Goncalo Alves which came with it.

Rubberized grips are great for shooting. My boss at that pistol range likened their recoil absorption to rubber tires, as opposed to the metal rims of the wooden wheels on a Conestoga wagon. With rubber, you feel fewer of the bumps in the road.

Rubber (or rubberized plastic) grips have two drawbacks for defensive carry:

- If one is carrying concealed, cloth over the grip tends to drag on the rubber, instead of sliding smoothly across it. This makes it easier to tell that one is carrying a gun under one’s shirt.

- If one is in reactive mode, as good guys usually are in gunfights, the hand seeking to grip the pistol does not slide around the grip quite a smoothly until it is in the correct spot, as it should be before drawing from the holster. This slows the draw ever so slightly.

Concealment was not an issue, as I carried openly, on that Sam Browne belt. There was no lawful concealed carry in Arizona in the mid-1980s.

The Sarge Saves Me

During that two-year period, the only between 1980 and 2017 when I wasn’t at least a part-time government employee (I was, instead, a Reservist on inactive status), I had an experience which could have gone very badly were it not for the sudden presentation of the Sarge. The lessons of that day can be found in Stuck in the Second O. I’ll spare you the details here, but I often use that story in my classes to illustrate OODA concepts.

Suffice it to say I learned some very valuable lessons that day. When I had no gun, I had big problems. Three big, hairy, smelly, drunk problems. When the gun came out, my problems went away. Correlation can be a logic fallacy, but I took those lessons to heart. Since then, I’ve made it a policy to be armed whenever possible.

Fortunately, my career gave me license to do just that, even on civilian airliners.

Smooth vs Serrated Triggers

One final advantage of that Model 586 over the Model 15s I’d carried for the Air Force was it had a smooth surface to the trigger. The Model 15 had a “target” trigger, with vertical serrations in the face of the trigger.

Serrations are OK when one is placing the tip of one’s finger on the trigger, shooting slow fire at bullseyes in Single Action mode, as the early K–frames were intended to be fired most of the time.

However, most gun battles occur at conversational distances. For closer range, rapid fire, double action “combat” type shooting, a smooth surface to the front of the trigger allows it to cam around in the crook of one’s first knuckle more easily and comfortably.

I’m sure the execs at Smith & Wesson didn’t mind when smooth faced triggers became the trend, as they were no doubt less time and resource consuming to manufacture than the serrated triggers.

Mon Colonel and the Sarge

My relationship with my father was often somewhat strained, especially in the years after I flunked out of the AF Academy. He was a career fighter pilot who’d flown in WWII, Korea, and Southeast Asia.

I remember being quite proud when I showed him the Sarge. Handling it, he said something like “That’s a big beast, isn’t it?” It was heavier it was than the Smith he’d carried in the cockpit of his F-4 Phantom II over North Vietnam.

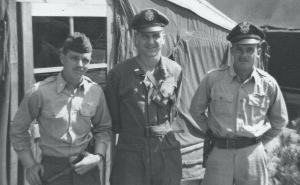

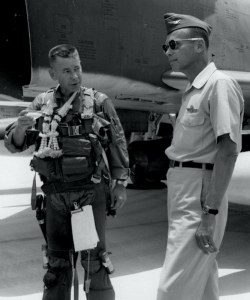

That’s my father, left, standing next to (then) LtCol Arnim L. “Lum” Brantley, 555th Tac Fighter Squadron Ops Officer, probably at Udorn Royal Thai Air Base, shortly before Christmas of 1968. I believe those festive garlands and beer steins were because they both just completed their 100th combat mission over Southeast Asia. I surmise it was their hundredth “counter” because in adjacent photos in that album, they were then stripped of their parachute harnesses and survival gear and blasted with a water hose. Then three Thai ladies peeled their wet flight suits off of them (right there in front of God and everybody). They donned emerald green “party suits” festooned with insignia including “Yankee Air Pirate,” “SA-2 Flight Examiner,” and the coveted “North Vietnam 100 Missions” patch, before being paraded around the flightline on a bomb jammer (loader, used in this situation as the 20th Century USAF equivalent of a triumphal chariot), with much fanfare and revelry. As the old beer ads used to say,

“Now, it’s Miller time.”

The Sarge was the first handgun, indeed the first gun, I ever owned. Having it strapped to my side at work, and showing it to my father, made me feel like a full-fledged citizen, like a warrior–things I had rarely felt before in mon Colonel’s presence.

Physically, my father was not a tall man, but he was always larger than life to me. He’d commanded the AF’s famed 555th “Triple Nickel” fighter squadron in combat, and was later a wing commander. He had a body like Rick Moranis, but a voice, and a command presence, like Darth Vader.

I gave my father some ammo for Christmas, with a promise to take him to a firing range, but we never went shooting together, ever.

I learned from that. I take my family shooting.

Trading Up to the M1911A1

In ’85, I swapped the Sarge for a surplus GI .45 like the kind my dad carried over Korea.

I’ve never regretted making that swap. I loved that Smith 586, but I certainly couldn’t afford to buy an auto pistol on the salary I was making at that firing range.

I’ve also never regretted marrying my wonderful spouse of three decades plus. But like looking at an old prom picture of the person you dated in high school, I still sometimes smile with pleasant nostalgia when I remember that Model 586.

Part III

USAF Security Police Sidearm

Smith & Wesson Model 15, again

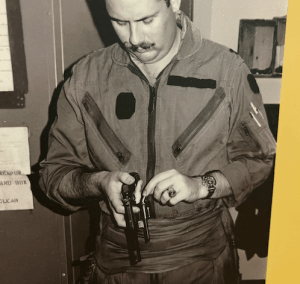

In 1986 I went back on active duty as an enlisted USAF Security Policeman. My first assignment was as a gate guard at a SAC nuclear missile base. We carried the Smith Model 15 revolver during entry point and traffic control duties.

I named my issued Model 15 “Lieutenant Gorman,” after the well-meaning but ineffective platoon commander from Aliens.

In those days I was a huge proponent of the .45 ACP over all other cartridges. Like the hapless Space Marine Lt in that movie, I expected my issued .38 (sn K870537, 90th Security Police Group armory rack number 92), with its jacketed round nosed ammo, to have good intentions, but perhaps to be ineffective in a fight.

.38 vs Polar Bear: Not a Good Idea

I had attended SERE, Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape school, in 1982 (we pronounced the acronym “sear-ee” back then; these days, the kids call it “sear”). We spent just over a week in the woods of Sailor Park, CO, at 10,000 feet ASL, and about half a week in a mock POW compound WSW of Jack’s Valley–plus numerous lectures and exercises beforehand.

During the SERE Arctic Survival lecture, they told us about some of the great stuff you can get from a dead polar bear, like food and fuel and fur garments. Then we were discouraged from stalking or being anywhere near one. The instructor told us:

“If you plan to use your issued .38 to take down a polar bear, be sure to file off the front sight first.”

Getting nothing but bewildered “deer in the headlights” looks from us students, he continued, “That way it wont hurt as much, when he shoves it up your ass.”

.38 vs Polar Bear: A Case Study

Later, I took a Revolver to Auto Transition Instructor course from Peter Tarley (formerly of the USAF OSI), who showed us a news article about one of NYPD’s finest, Patrolman Charles Dlugokecki.

In New York on June 5, 1971, an idiot jumped the rail and stuck his arm through the bars into the Polar Bear exhibit at the Central Park Zoo. Thankful for the snack, the bear began munching his hand.

Officer Dlugokecki ran to the scene of the commotion and fired a warning shot into the air (probably not a good idea in NYC, but possibly required by policy at the time). He was probably using a Colt Metropolitan Mark III or a Smith Model 10, both of which were .38s authorized by NYPD in 1971. The bear responded by chewing the idiot’s wrist.

Dlugokecki fired another warning shot, but instead of letting go, the bear chomped his way up to the stupid idiot’s forearm.

The officer interrupted what was clearly a case of natural selection in action by firing a single .38 slug into the left side of the bear’s chest. The bear let the idiot go, staggered over to an adjacent fence, and died (“Bear Killed to Save Man Who Put Arm Into Cage,” by Martin Gansberg. NY Times, 06 Jun 1971).

NYPD issued round nosed ammo at the time; NYPD did not convert to hollow points until 1999, and was the last major metropolitan police department to do so (Massad Ayoob, “The Dangers of Over-Penetrating Bullets,” Gun Digest, 19 Apr 2012).

I have a hard time feeling sorry for idiots who break the law and get hurt in the process. The only victim I see here is the bear, who was probably as domesticated as polar bears can be. Like most cops, Officer Dlugokecki was upset that the idiot had forced him to take a life. He issued that jackass a summons for feeding the animals.

The main lesson here:

Even a moderately powered .38 may do, if you put it in the right place.

USAF’s PGU-12/B

With the USAF .38s, I didn’t know how good I had it at the time. Due to Geneva Convention concerns, we weren’t supposed to carry hollow points. Even though we were securing a Stateside nuclear ICBM base, we were deployable to foreign wars, as I experienced in person shortly after we transitioned from the Smith & Wesson to the Beretta M9 (see Worm Was Right There With Us). The laws of armed conflict prohibit arms and ammunition “designed to cause unnecessary suffering.”

Which is asinine, because:

ALL weapons and ammunition are designed to cause unnecessary suffering.

Some are just more effective than others.

The USAF has since issued “controlled expansion” (fancy word for hollow point) ammo in certain situations, especially Stateside.

But back then, being stuck with round nosed jacketed “ball” ammunition did not mean the USAF had to leave it at that. The Air Force adopted a special high velocity cartridge, designated PGU-12/B.

The Air Force previously had another proprietary .38 Special cartridge, the 130 grain, jacketed round nose M41. It had even less power than standard .38 Specials, as it was designed to not blow up aluminum M-13s.

After adopting the much sturdier Model 15, USAF had the manufacturers shove a 130 grain jacketed round nose projectile deep into the cartridge case. They crimped the case mouth over the ogive (rounded shoulder) of the bullet till only the top 1/3 stuck out, giving the cartridge a stubby, “uncircumcised” appearance.

This literally over-the-top crimping not only compressed the powder charge. It also held tighter to the projectile just a few nanoseconds longer, allowing the pressure to build up more before the bullet broke free and jumped into the barrel.

This resulted in higher (+P or even +P+) velocities, and probably beat those K frame Smiths up a bit, although I’m unaware of any catastrophic failures caused by our always training and qualifying with that “full house” PGU-12/B ammunition.

Active AF Retires the Model 15s

In 1988, us active duty Sky Pigs traded in our Smith Model 15s for brand new Beretta M9s.

By that time, I’d promoted out of the Gate section and was, for the remainder of my first six years with the Security Police, a rifleman by trade. I only drew a handgun on days I was assigned an M60 machine gun (during Ops Desert Shield & Desert Storm; if memory serves Stateside SP ’60 gunners didn’t draw a pistol), or during special courier type details. We would also, occasionally, assign pistols to those guarding M16s in training exercises, for the same reason as when I was on the TLD before: to keep live rifle ammo from sneaking in with the blanks.

I didn’t end up carrying the M9 full time till I went back into the Security Forces career field as a guardsman & reservist in this century. See upcoming post The Berettas for info about the M9s.

SPs were Arming Category A: armed all the time as part of their duties. It took a while for the M9s to filter into the other arming categories (B, armed in wartime, like pilots) and C (only armed in certain situations). In Operation Desert Storm (1991), F-15E pilots still flew with issued Smith Model 15 revolvers (Smallwood, Strike Eagle, p. 120), although some got away with carrying privately owned weapons like Glocks (p. 88). Our leadership ordered us to only carry issued weapons when we deployed to Desert Shield / Storm, but even at that we were relatively well armed.

Part IV

Aeromedical Evacuation Crew Arms

S&W Model 15 . . . yet again

In 1992 I got off active duty the second time, transferred to the Air National Guard, and cross-trained into the flight medics performing AeroVac (aeromedical evacuation) on C-130Bs (and, later, C-130H-3s). The Wyoming Air National Guard was still issuing .38 revolvers to deploying aircrews for counter-hijack duty (and to medics on the ground in combat zones, like Somalia, for protecting the patients), so I got to qualify with the Smith & Wesson Model 15 once or twice more before the ‘Guard, too, transitioned to the M9.

In the Air Guard, we almost never carried pistols on Stateside missions. I rarely saw them unless and until we were qualifying.

I “Guard bummed” my way through the remaining 2 years of my 14 year college career, which culminated in a 4 year Bachelor’s in Justice (don’t judge me; only 6 of those 14 years were full time). As an aircrew member, we got to fly a few times a month, in addition to our one weekend a month and two weeks in the summer, which (along with VEAP and my devoted spouse’s full time employment) paid for both the mortgage, school, and my off-duty ammo habits (which were high volume, but cheap in per-unit terms, in those days).

Part V

Off Duty Wheel Guns and Backups

The Tools of Professional Pistoleros

I was a full-time rifleman by trade from 1988 to 1992 (see Getting Iron for the Bullhorn god), and again during an active duty call-up in 2008. For the most part, from 1996 on, I was paid to be a pistolero. I carried a succession of semi-automatic pistols as my primary duty guns at work. I carried a long gun whenever I could when I was patrolling the Rio Grande (see Backing Up Beaker), and when serving warrants as a special agent (see The Evolution of Police Long Guns), but handguns were my constant companions on and off duty. From 1996 on, I even carried pistols on commercial aircraft.

I stopped carrying wheel guns at work, except as backups or when clothing options prohibited the concealment of a larger auto (see J-frame Snubbie BUGs below). While many, many bad guys have fallen to six-shooters, even this inveterate wheel gunner had to admit that they are mostly outdated gunfighting technology. I find it amusing that the types of revolver I once bought because I couldn’t afford a semi-auto are now boutique items, retailing for 2 – 3 times the cost of a Glock. Older, pinned barrel Smiths command especially high prices from collectors.

Revolvers have some advantages, especially for older people with arthritis or other issues that make it difficult for them to operate the slide on a semi-auto. Revolvers are far easier for the weak handed to manipulate (load / unload). There is usually enough leverage for even those with weaker hands to thumb cock a revolver.

While this does not make for very rapid or high volume fire, it certainly helps those same weaker handed people to pull the trigger (single action trigger pulls tend to be smooth and light). The noise of the hammer thumb-cocking, which I once heard around a corner in a house at 0200, may also give a potential opponent pause.

Cops work nights, weekends, and holidays. Many of us who carried auto pistols for a living still had a revolver or two around the homestead for our spouses to use for bumps in the night, while we were away saving the rest of the world.

Square Butts and Round Butts

There are oodles of different revolver grips out there, but each must fit onto the grip portion of the frame. Smith frames with squared bottom edges to the grip are called Square Butts, and those that have rounded bottom corners, well–you guessed it.

Generally, the smaller and more concealable the revolver, the more likely it is that it will have a round butt–but not always. The first revolver my wife shot was a tiny square butt J-frame Smith Model 31-1 in .32 S&W Long. Her father had died; they lived out in the country, and her mom decided they needed something for protection.

The back bottom corner of a square butt pokes out, making it harder to conceal, so square butt J-frames are relatively rare.

Anybody who would be interested enough in their snubbie to buy aftermarket grips for it, probably would get a round butt in the first place, so aftermarket square butt grips for J-frames are hard to come by.

Round butts are generally easier for smaller hands to wrap around, but sometimes they are counter-productive. Pressing the bottom of the palm against the lower rear corner of the grip provides leverage for those with weaker hands to hold up the front of the gun.

Almost all the Smith L-frames had square butts. Smith & Wesson made a custom–no pun intended–Model 686 with a round butt for the US Customs service, and some few round butt L-frames wound up marketed to civilians. Great gun by all accounts, and easier for smaller agents to get their hands around. But that lug up under the barrel was heavy and hard to hold up.

When I first went to FLETC, the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, I had a classmate named AJ who was a Tejano by birth, but a ragin’ New Orleans Cajun by upbringing. As we negotiated the different hairpin turns on the racetrack during the pursuit (EVO: Emergency Vehicle Operations) course, AJ would have his left hand on the wheel, and his other hand on the radio mic, requesting an “am-boo-lance.” Before FLETC, AJ hadn’t spent much time in a gym, but he was the fittest agent in our class, as he’d grown up lifting stacks of 2x4s and swinging hammers whenever he wasn’t in school. He worked at his father’s construction business.

AJ’s bride and mine were both very attractive. They used to turn quite a few heads when they went out to eat or shop in the lower Rio Grande Valley.

AJ had a Smith Model 686 (L-frame) that his lady was having difficulty mastering, and I was a firearms instructor, so he requested my assistance.

I told him her issues could probably be cured with grips that fit her hands well. I brought over several different square butt grips that I assumed would fit his L-frame Model 686, for her to try.

That was when I discovered that their Smith was one of those rare CS-1 type round butt 686s. It had very small Pachmayr grips that did not cover up the back strap. Plus, it had a 6 inch barrel, with that full length underbarrel lug.

She had very long, thin fingers. There simply wasn’t enough grip, especially in back, by the base of her palm, for her to lever up the front of that long barreled, heavy lugged L-frame.

When he asked if I had diagnosed the issue, I said “The problem is, she has a little round butt. I mean, I like it–it feels great in my hand–but there’s just not enough there to hold on to . . .” It took me a second to figure out why the veins were beginning to bulge out on the side of that rowdy ragin’ Cajun’s neck.

Unfortunately, grips for round butts won’t usually work with square butts, and vice versa, even if they are for the correct sized frame.

J-frame Snubbie BUGs

Periodically throughout the 21st Century half of my career, I did carry small J-frame Smiths as back-up guns (BUGs) while on duty.

J-frames and BUGs in general are a study unto themselves, so I’ll catch you up on them in their own article. Thanks for wading through all of this. ‘Til next time,

–George H, lead instructor, Heloderm LLC

Appendix I:

Fun revolver facts: Releasing the cylinder

- On a Smith & Wesson, as well as smith clones like the Astra, push FORWARD on the cylinder release latch.

- With a Ruger, you push IN on the latch.

- With a Colt, you pull BACK on it.

- With some versions of the Korth, the cylinder release is a lever next to the hammer.

- With Dan Wessons, the lever is on the crane, and you press DOWN on it.

Appendix II:

PPC Smiths

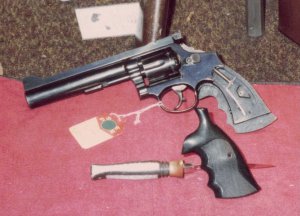

Before Action (IPSC / USPSA) competition became mainstream, the closest thing most cops got to practical shooting competition was NRA PPC: Police Pistol Combat matches.

PPC was essentially a glorified qualification course. There were lots of skill level categories, so just about everybody walked away with some sort of medal, trophy, or ribbon.

There were different categories of firearms as well. Just as there is nothing “stock” about a racing “stock car,” people came up with all kinds of modifications to give them an edge in PPC comps. PPC rule books got into the weeds of which modifications to your pistol put you in which category.

PPC was supposed to be practical, which is to say, tactical. Like you would shoot your duty gun on the street. When revolvers ruled the law enforcement roost, double action only was the practical / tactical order of the day. It was assumed you would have neither the time nor the inclination to thumb cock your revolver in a fight.

However, PPC included some barricade shooting at distance, and at distance is where the single action option of a selective DA / SA revolver really shines.

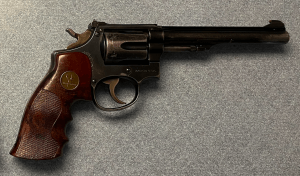

This PPC revolver, which I’m guessing started life as a K-frame Smith, has had the standard Smith flat hammer spring removed and replaced with a coil spring. The hammer spur has been removed.

The only reasons I can think of for those modifications are, because the tension of a coil spring “stacks” noticeably the more it is compressed, the coil spring enables the competitor to set the handgun up for a single action pull, without cocking the pistol. The missing hammer spur is a specific reminder that the competitor would have difficulty thumb cocking.

Pulling the trigger, the competitor can feel that coil spring stack, till it is about to break. The shooter then pauses, refines the sight picture, and then gently squeezes off a short-stroked trigger pull like a single-action shot.

Theoretically, a person in a fight will be in too much of a hurry to be staging the trigger like that, except for distant shots where precision is extra important.

If it is, say, for a well-considered head shot on a hostage taker, with a duty revolver, one could simply thumb cock and keep the finger off the trigger till the shot becomes necessary. Most duty shooting being of a more immediate necessity with less precise marksmanship demands, one would normally plan to roll through the trigger consistently and as rapidly as one could in a controlled manner.

But the person buying a revolver with a 6″ bull barrel and a huge rib with extra mondo high visibility sights and a screw in the back of the trigger to prevent over-travel is clearly getting it to compete with, not for practical street carry.

Some handgun modifications improve its ability as a fighting tool. Many custom handgun modifications are unnecessary. Some are even counterproductive. Most are more effective for bragging about than they are for giving you any sort of edge. At least, not the kind of edge you could get if you simply invested the same amount of money in more training ammunition, and practiced with it, instead.