Getting Iron for the Bullhorn God

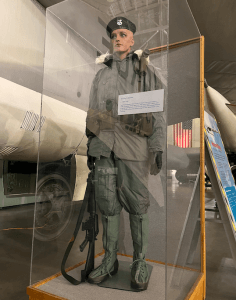

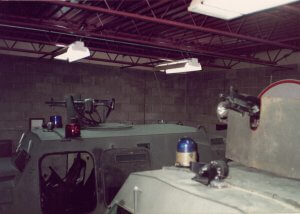

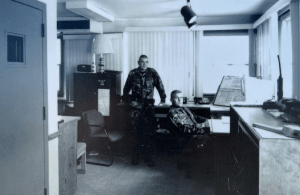

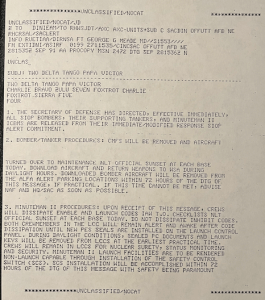

SMSgt Ferguson firing a ComBloc PKM during OpFor training at Ft Carson

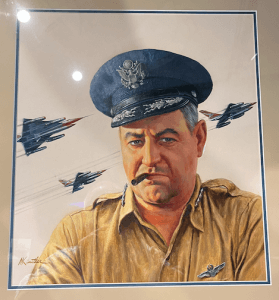

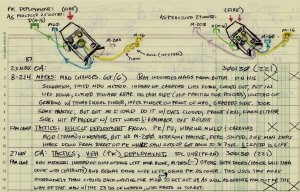

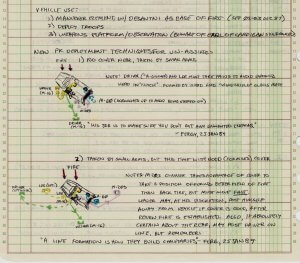

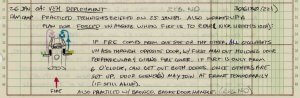

MSgt (later Senior Master Sergeant, or SMSgt) Ferguson was the superintendent and coach of our Olympic Arena team, during the 1988 and 1989 seasons.

To understand how SMSgt Ferguson’s story intersected with mine, you must first know a little bit about Olympic Arena. OA was a command-wide competition between the various Strategic Air Command (SAC) missile bases.

SACumcised

The Cold War (1945 – 1989) was, as Eric Schlosser pointed out, the single longest period of peace between Europeans in recorded history. I always intended to be on the front lines of the Cold War, facing down the Evil Empire across the Wall by day, and drinking Bitburger Pils in German gasthouses (or Guinness Stout in British pubs), by night.

Instead, I wound up on what the USAF calls the Northern Tier: the vast regions of North America’s plains that were home to SACs ICBM (intercontinental ballistic missile) and bomber / tanker fleets.

Work on the Northern Tier could be grim. It was not entirely unlike serving in the Night’s Watch in the HBO series Game of Thrones.

Earlier in my career I’d been advised, quite wisely, that if they told you your next base “had great hunting and fishing,” that meant you were screwed.

My flight sergeant from Desert Storm told me that when he was a young airman he volunteered for duty in Vietnam, just to get away from Grand Forks, his northern tier SAC base, halfway between Fargo, North Dakota and the Canadian border. He’d been pulling close-in sentry on a nuke-loaded B-52 when they got stranded on the aircraft parking ramp by a snow storm.

Minot AFB, also a few miles from the Canadian border in North Dakota, was the ultimate Northern Tier base. “Why not Minot?” asked the rhetorical question known throughout the Air Force. The inevitable response was “Freezin’s the reason.”

To which the “Rough Riders” stationed at Minot might reply that, like the blue button on my hat says, “Minus 41 degrees (Fahrenheit) keeps out the riff-raff.”

It wasn’t just the extreme weather of the windswept northern plains that made working for SAC such a depressing chore. Norway gets cold, too, but the Air Force attaché at our embassy in Oslo probably had much better morale than most folks on the Northern Tier.

Mostly, it had to do with the nuclear mission.

The ICBM Mission

The ICBM Mission

. . . kinda sucked, compared to, say, the tactical fighter mission.

Our fighter pilots train hard, in case their skills are ever needed. An A-10 pilot doesn’t want to kill the crew in an enemy tank. But if she does, she at least has the consolation of knowing that some American GIs are more likely to go home to their own families. SOMEBODY in that fight will be happy she did her job, and did it well. Besides–and I can tell you this from personal experience–there are few things more fun than high angle strafe.

For ICBM launch crews, NOBODY, especially not them, will be happy if they end up having to do their job. It might safely be argued that their job is to be so good at what they do, such a credible deterrent, if you will, that they NEVER have to do what they constantly train to do.

This poem pretty much sums up what it’s like to be a missileer on an ICBM combat crew:

In vacant corners of our land,

off rutted gravel trails,

There is a watchful breed of men,

who see that peace prevails.

For them there are no waving flags,

no blare of martial tune,

There is no romance in their job,

no glory at high noon.

In an oft’ repeated ritual,

they casually hang their locks,

Where the wages of man’s love and hate,

are restrained in a small red box.

In a world of flick’ring colored lights,

and endless robot din,

The missile crews will talk awhile,

but soon will turn within.

To a flash of light or other worldly tone,

conditioned acts respond.

Behind each move, unspoken thoughts,

of the bombs that lie beyond.

They live with patient waiting,

with tactics, minds infused,

And the quiet murmur of the heart,

that hopes it’s never used.

They feel the loving throb,

of the mindless tool they run,

They hear the constant whir,

of a world that knows no sun.

Here light is ever present,

no moon’s nocturnal sway.

The clock’s unnatural beat,

belies not night or day.

Behind a concrete door slammed shut,

no starlit skies of night,

No sun-bleached clouds in azure sky,

in which to dance in flight.

But certain as the rising sun,

these tacit warriors seldom see,

They’re ever grimly ready,

for someone has to be.

Beneath it all they’re common men,

who eat and sleep and dream,

But between them is a common bond,

of knowledge they’re a team.

A group of men who love their land,

who serve it long and well,

Who stand their thankless vigil,

on the brink of man-made hell.

In boredom fluxed with stress,

encapsuled they reside,

They do their job without complaint,

of pleasures oft’ denied.

For duty, honor, country,

and a matter of self-pride.

–Captain Robert A. Wyckoff, Missileer *

AF pilots affectionately refer to the missileers as “Coneheads.” Tom Cruise will never star in a movie called “Top Missileer” (or, for that matter, “Top B-52 Radar Navigator”).

Nuclear Deterrence

Many people, even some of those who are part of our nation’s ICBM and SLBM (submarine launched ballistic missile) forces, have a hard time wrapping their brains around the concept of nuclear deterrence. But it’s not entirely unlike you, as an armed citizen, when a grisly looking dude with a knife approaches your family. You point your gun at him and tell him to go away. You don’t want to kill him, but you damned-sure will, if he forces you to.

If the look in your eyes tells him that’s true, it’s more likely he will leave, and you won’t have to shoot anybody. You’re not trying to change him, or his way of life, or to nation build. You just want him to say to himself, not today, and to go away.

PRP: the Personnel Reliability Program

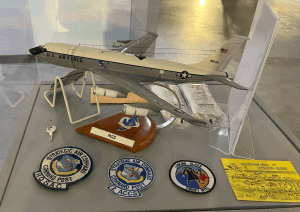

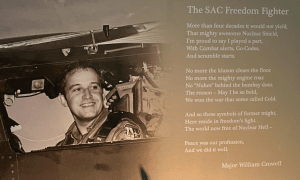

The emblem of the Strategic Air Command had a fist in a gauntlet, holding lightning bolts and an olive branch. SAC’s motto was “Peace is Our Profession.”

Because the stakes are so high with thermonuclear devices, mistakes were not tolerated in the Strategic Air Command. There was an unauthorized SAC patch you might encounter from time to time (but never where the commander could see it). Instead of lightning bolts and olive branches, the mighty Mailed Fist of SAC held a scrotum. The scroll along the bottom read,

To err is human; to forgive is not SAC policy.

All personnel who were even remotely involved with nukes were enrolled in the Personnel Reliability Program, or PRP. There were psychological tests. Commanders had to personally interview each of their personnel. Even Treads like me had to have a Secret clearance.

If you got flagged under the PRP, you were suspended from duty. A parking ticket or minor moving violation might not jam you up with the PRP, but just about any other involvement with the law would. Certain medications could knock you off. Even Tylenol would. Consequently, AF docs prescribed ibuprofen for just about every condition, from broken bones to pregnancy. Of course, numerous medical maladies (including those) would also knock you off the PRP.

The zero-defects, checklist mentality of SAC jobs became a grind after a while.

At flying bases, the maintenance types could say “We generated X number of sorties (flights) this month” (or “this quarter” or “this fiscal”). There was a small UH-1 Huey helicopter detachment supporting each missile wing. Ours was Detachment 10 of the 37th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron (the 37th ARRS had flown Jolly Green Giants out of DaNang in ‘Nam). But if anybody else on base generated a sortie–an ICBM sortie–something was seriously wrong. In other words, if you did your job right, there was not much to do, and very little to report.

All the more so in the Security Police groups. At least the Communications squadron types could say, “I fixed three broken radios today.” What could the sky cops (also called sky pigs, for SPs, or Security Police) say? “My flight had 10 missiles at the start of my shift. Nobody stole any of them on my watch.”

Frankie’s Rocket Ranch

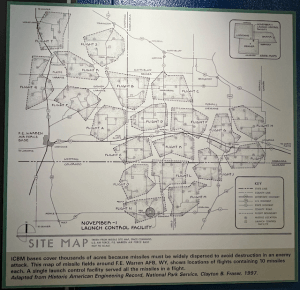

I lucked out, being stationed at Francis E. Warren Air Force Base in Cheyenne, Wyoming, on the balmy southern shores of the Northern Tier. FE Warren AFB, originally Fort DA Russell, had been an Army Cavalry post before the Air Force existed. President Lincoln established the post to protect a railroad crossing over Crow Creek, which ran right through the base.

There were roughly 1100 cops–by that, I mean badge wearing, gun toting Security Police men and women–in the 90th Security Police Group at FE Warren. Most of the time, most of them were not actually at FE Warren, but rather scattered throughout our enormous missile field, which covered SE Wyoming, western Nebraska, and NE Colorado.

It took so long to get to the missile sites–some were several hours away from the main base–that we would stay out there for three days and nights, then come back on the fourth day. The Missileers downstairs pulled 24 hour shifts in their launch capsule. Unless a bad snow storm hit, in which case all bets were off.

It took so long to get to the missile sites–some were several hours away from the main base–that we would stay out there for three days and nights, then come back on the fourth day. The Missileers downstairs pulled 24 hour shifts in their launch capsule. Unless a bad snow storm hit, in which case all bets were off.

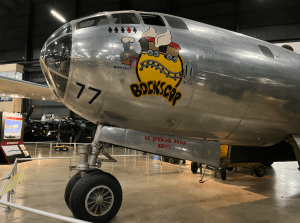

To build and maintain morale, SAC got some special dispensations. The bomber and tanker crews were allowed to paint (relatively tasteful, pre-approved) nose art on their planes, to remember their WWII heritage. I met an all female tanker crew with a painting of Fabio, the broad-chested romance novel cover model, on their KC-135.

This very feminine tanker pilot stands next to Nordic Thrust, with masculine nose art inspired by Frank Frazetta’s painting “Dark Kingdom” (which also wound up on the cover of Molly Hatchet’s Flirtin’ With Disaster album).

The ICBM bases had Olympic Arena, also called Missile Comp, short for Missile Combat Competition.

The Ferguson Weight Loss Program

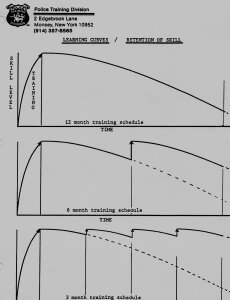

The Olympic Arena training season lasted from roughly December through May of the next year, when the competition was held at Vandenberg AFB in Lompoc, California. Competitors were relieved of other duties so they could focus completely on preparing for the competition.

As with the International Olympics, there were several different disciplines.

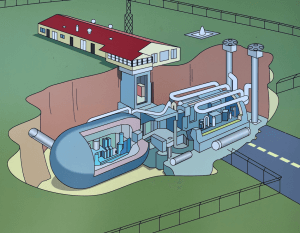

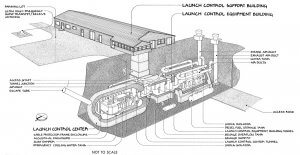

Missileers, for example, competed against missile crews from the other bases. Their part of the competition was Top Secret, and took place in a launch capsule simulator.

The Comm Squadron teams competed against Comm troops from other bases. In their competition, they would be given a piece (or several pieces) of broken communications equipment, and graded on how well they trouble shot and repaired it.

There were also missile maintenance teams, missile handling teams, and Facility Managers competing. FMs maintain the equipment at the Launch Control Facilities (LCFs).

The Security Police teams competed in three different ways:

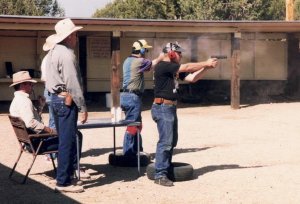

- A biathlon type live fire shooting match, where we ran, shot, ran some more, shot some more, etc. We primarily shot M16 rifles, but also M203 grenade launchers and M60 machine guns, at pop-up targets.

- One or two tactical exercises. These scenario-based exercises used MILES, the Multiple Integrated Laser Engagement System (see below). OpFor (Opposing Forces, playing heavily armed terrorists seeking to gain control of a nuclear weapon) were select members of the SAC Elite Guard out of SAC HQ at Offut AFB, Nebraska. The Air Force sometimes called OpFor role players or pilots “Aggressors.”

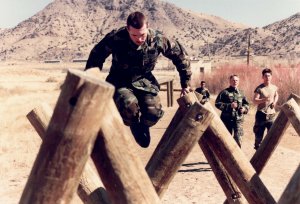

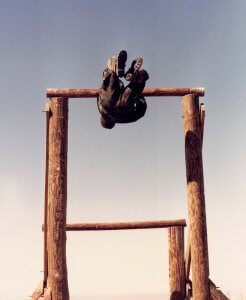

- A 1.5 mile long obstacle course. SAC called it a “confidence course.” I was confident that, each time I ran it, I would be wishing I was somewhere else, doing anything else, before it was done.

OA Tryouts

Of the 1100 Sky Cops in our group, only 11 to 14 would be selected for the team. 14 out of 1100 sounds pretty exclusive (it was), but in fairness, only one or two hundred SPs, if that many, actually tried out.

Everybody knew that training up for the comp would be no picnic, and not everybody was interested in putting out that much effort for no change in pay. Much easier to sit on a couch at a launch control facility (LCF) in Nebraska, staring at Baywatch till an alarm went off at a missile site (LF, or launch facility).

I had my reasons for trying out.

Part of it was the family business. My father had been on the 50th Fighter Wing gunnery team when he flew F-86s in the mid 1950s. They won first place in the USAFE (United States Air Forces in Europe).

Mainly, for me, though, it was the opportunity to train to a higher standard–and for the free ammo. I got to shoot easily 10 times more bullets (and 20 times more blanks) in any one of my three seasons as an OA competitor than most SPs got to shoot in their entire careers.

The initial selection process was mostly physical (how many pushups / pullups / situps you could do, how fast you could run, etc.), combined with an examination of your shooting scores (recorded on AF Forms 522), and perhaps peer or commander evaluations. At least, that’s how it was my first season, Dec ’86 to May of ’87, when our coach was MSgt Cole. For some reason, they called it Olympic Shield in ’87.

The following year, when SAC went back to calling it Olympic Arena, SMSgt Ferguson took over the team. MSgt Cole had been professional, if informal. SMSgt Ferguson’s approach was somewhat more involved. After reviewing our 522s to see what our previous shooting scores were, SMSgt Ferguson had us shoot for score as part of the tryouts. Just ’cause you were on the team before, or shot well when it didn’t matter, didn’t make you a shoe-in this year.

As with on the street, it was how well you could perform on demand that counted.

During tryouts for the following (’89) season, SMSgt Ferguson even introduced tactical skills and field leadership evaluations as part of the selection process. He would give us NCOs (non-commissioned officers, or sergeants) a handful of troops and an objective to seize. “The traffic cone in that open field over there is the Resource” (the nukes were called “Priority A Resources”). “It’s been taken by an unknown number of bad guys. These men are your fire team. You have 10 minutes to take it back.”

He graded us on how quickly we came up with a plan, how good our plan was, how we communicated the plan to our troops, and how well we implemented it. Different NCOs had different levels of tactical acumen, but most of the above were basic NCO leadership skills we’d all trained on.

Of course, there was a twist.

Unbeknownst to the NCOs trying out, SMSgt Ferguson had instructed some of the junior troops on our fire team to NOT do what we told them to do, or to do it wrong.

The tryouts took place at the base “Fam Camp,” which was along Crow Creek. That was about the only part of FE Warren AFB, which was on the high plains, where there were any folds in the terrain or brush to hide behind. Vandenberg AFB, where the competition would take place, was on the coast of California, and had plenty of such terrain features.

It being December in Wyoming, Crow Creek was mostly frozen over. I split my team into two elements and ordered them to move up each side of the creek toward the resource.

One young airman steadfastly refused. “Un-uh. I’m not going to do it.”

“Not going to do what?” I asked. It’s not unusual to have to clarify orders when a subordinate does not understand instructions, but outright refusal was completely unheard of. It’s not like I was asking him to shoot civilians in a ditch at Mỹ Lai. I didn’t know Fergy had put him up to it.

“I’m not crossin’ that creek. I, uh”–he fished around for a plausible excuse–“I could fall through the ice.”

“Listen,” I said, somewhat flabbergasted, “I wouldn’t ask you to do anything I wouldn’t do myself.” I ran back and forth across the frozen creek a few times, to show him it would hold his weight. “See? Now get your ass over on that side of the creek and move out.” Can’t remember if I added “or I’ll kick it over there,” but I know I was thinking it.

He sheepishly complied. In retrospect, I think he was as uncomfortable not following orders as I had been to have mine refused.

“We follow orders, or people die. It’s that simple.”

–Jack Nicholson, as “Col Nathan Jessup,” in A Few Good Men

Later, as we made our way up the creek, I heard a crunching noise, and a splash. I looked back and saw that he had indeed fallen through the ice (Crow Creek was only about knee-deep at that point). I felt bad for the guy. I also felt bad that part of me wanted to smirk.

By my third season, I’d fallen though that ice more times than I could remember. It was chest-deep in some places. We trained in and around Crow Creek all winter; it was the only place there was any concealment. “Surf’s up,” we used to say, on our way to the creek.

SMSgt Ferguson wanted us to bring ALL our gear, every day, so we could change our training plans at a moment’s notice. Our other team motto became “Semper Gumby:” always flexible. One of the wives made our team a “Surf Crow Creek” T-shirt with Gumby on a surfboard, rifle strapped across his back.

The first year SMSgt Ferguson selected me for the OA team (in November ’87, for the April ’88 competition), he told me he picked me because I couldn’t run.

I was confused.

“You run all wrong,” he said. “You run on your toes, instead of your feet landing flat or even heel-toe. Any normal person would quit after a few miles. But you just keep going. If we can teach you to run correctly, we might have something.”

I took it as a compliment, of sorts.

“The clock is ticking, and as of now, we are keeping score.”

–Michael Ironside, as “Jester,” in Top Gun

Making the initial cut was only the first phase of the battle. The team had 11 – 14 cops so we could have some depth to the bench. It was not unusual to lose a few to injuries along the way (people had actually broken their necks and died on the obstacle course). Of the 12 or so who got onto the team, only 7 would eventually make the Primary team that competed at Vandenberg. The others would be Alternates, second-string benchwarmers. I wound up as an Alternate my first (’86 – ’87) season.

Making the initial cut was only the first phase of the battle. The team had 11 – 14 cops so we could have some depth to the bench. It was not unusual to lose a few to injuries along the way (people had actually broken their necks and died on the obstacle course). Of the 12 or so who got onto the team, only 7 would eventually make the Primary team that competed at Vandenberg. The others would be Alternates, second-string benchwarmers. I wound up as an Alternate my first (’86 – ’87) season.

The Primary team wasn’t selected till some months into the training season, so in essence, every single day was a tryout.

“The only easy day was yesterday.”

–Navy SEAL motto

It was always very physical, but the first several weeks were one continuous “smoke session.” Or maybe it all was, and our bodies simply became inured to the stresses.

Like lugging that log around. SMSgt Ferguson had us work out with a telephone pole.

Yes, an actual telephone pole.

Great team building exercise, but gets old mighty fast. It was a little more bearable (no pun intended) for me because, as a much younger man, I’d read a book about Darby’s Rangers in WWII. They’d trained with logs, too. That was the sort of conditioning I’d signed up to get, but was all too rare in the modern military–even in the Security Police, the Infantry of the Air Force.

SMSgt Ferguson also had us run “the Gauntlet.” We were to make it from Point A to Point B while two NCOs, who competed in trap & skeet, shot at us with MILES lasers (see below for more about MILES).

Those two laid waste to us.

Before the Gauntlet, we called them the Ducks Unlimited Liberation Front. Afterward, we called them the Two-Shot Terrorists. No matter how tiny the opportunity we gave them, they swung through our movement like we were clay birds, and popped off two rounds of M200 (5.56mm blank) ammo quicker than you could blink. They locked us out every time.

When we fought against other, conventionally trained SPs (who had mostly just shot at static targets with live fire), we did OK. But against trap shooters who were accustomed to shooting at rapidly moving targets, we got massacred. The flip side of that coin is, if YOU want to get good at fighting, you have to train against living, breathing targets who do not want to be shot. Prior to MILES, marking cartridges (paint pellets), and Airsoft, the only practical way to do that was by hunting animals, although I had experimented with primer powered cotton balls out of revolvers in the first half of the 1980s.

Sometimes, during the Gauntlet, SMSgt Ferguson would shoot blanks at us himself.

I have a vivid memory of him borrowing my rifle to illustrate a point, and then throwing it back to me. It wasn’t a gentle lob, but it wasn’t malicious. It was just no-nonsense. I was expected to catch the rifle, and I did. I can’t really describe it, but his move both implied confidence in my abilities and exuded confidence on his part. Further, his attitude was that it was no big deal. There is a tendency among Air Force types to treat small arms with kid-gloves, and to treat those who must be armed as Barney Fifes. SMSgt Ferguson tossing me back that rifle “with authority” was exactly the opposite. Perhaps curiously, I found that to be immensely gratifying.

Speed is Life

We learned early that when you’re exposed in the open, “Speed is Life.” Like basketball, it was an endless series of short sprints. Unlike basketball, we did it in body armor, weighed down by ammo and other gear. As time went along, we got a lot harder to kill. But it was exhausting.

I remember coming to my girlfriend Susan’s house after a hard day of training, pretty early on in the season.

I was young and very fit, but I could barely move. We’d been doing PT and immediate action drills outside in the snow all day. She made me a bowl of soup to warm me up. I put my spoon in the bowl, filled it, and tried to raise it to my lips.

Halfway there, the spoon slowed and then stopped. It felt like it weighed 50 pounds.

I held it there, trembling, but I just couldn’t do it with one hand. I reached our with my other hand, grabbed my “strong” hand, and between the two of them, was able to get the spoon to my mouth.

The OA team trained 6 days a week. When it was time to go to work, Sue would send me out the door with a cheerful “Have a good day. Kill all the terrorists.”

A typical day would start with about 2 hours of physical conditioning. Then we’d head to the range and shoot till lunch.

Ferg brought in dietitians to brief us on nutrition, and implemented stricter dietary controls than in previous years. We were, in essence, professional athletes. We couldn’t smoke (not an issue for me) or drink booze, either.

The season wouldn’t officially end till we crossed the obstacle course finish line at Vandenberg, months later. At the culmination of the ’87 season, Technical Sergeant (TSgt) Aubrey C, whose dad had flown with mine in Southeast Asia, requested that someone be waiting at the finish line with a hot dog, a lit cigarette, and a beer.

I was always too busy puking after the O’ course for much of that, at least till after I’d sucked some O2 at the ambulance they had at the finish line.

TSgt Craig S, who was on the OA team during the ’89 season, came to us a heavy smoker. “I’ll fix that,” SMSgt Ferguson told him. And it worked. Craig hasn’t touched a cigarette since then, even after Scud attacks in Saudi, where he was my squad leader.

After lunch, during a typical training day, we’d spend the rest of the afternoon doing MILES exercises.

MILES

The Multiple Integrated Laser Engagement System, or MILES, was a way to do legitimate Force-on-Force HTE (Human Target Engagement) training, decades before Simunition FX and UTM marking cartridges became available as HTE training tools. Real opponents don’t just stand there like a cardboard target does. Any serious student of the craft simply MUST train force on force against living breathing targets that don’t want to get shot, and more importantly, shoot back.

Each participant wore a MILES harness, called a MWLD (man worn laser detector) in place of his or her load bearing equipment, or LBE. (The Security Police career field had been opened to women in the 1970s, and there were a handful in the 90th SPG; Kristine E. was on the OS team my first year.) The harness was covered, front and back, with several dome shaped laser receptors. There was also a crown-like band of miles receptors that fitted around your helmet.

An infrared laser bolted to the barrel of your rifle or MG. It had a microphone in it, activating the laser each time it heard a blank being fired. It shot two beams: a laser and a cone.

If someone hit one of your receptors with their laser, your system would “lock you out.” You’d know because a speaker on your left shoulder would immediately begin broadcasting a loud, high pitched, uninterrupted squeal.

I understand there have been psychological tests that determined the sound of a crying baby is the most irritating noise known to mankind.

Not true.

I changed plenty of diapers raising my kids. The squawk emitted by your MILES harness after you were “hit” was FAR more irritating than a crying baby.

Unlike a crying baby, it was always easy to make the wailing stop. All you had to do was to take the enabling key out of the laser transmitter on your weapon, insert it in its receptacle in your harness, and give it a quarter turn. We called that being “locked out” of the exercise.

We also, as a matter of protocol, took off our helmets and sat on them. That way anybody too far away to hear your gear go off would see that you were no longer among the “living” players in the exercise.

If you got hit by the cone, instead of the pencil-thin laser beam, your harness only beeped. That meant real bullets would’ve been cracking past you close enough to feel the breeze of their passing. If you were getting beeped a lot, you wound up doing what SMSgt Ferguson referred to as “the Beirut two-step.”

Downsides of MILES

MILES had some drawbacks. Photons didn’t penetrate brush as well as real bullets, but they bounced off of truck mirrors and even penetrated bullet resistant armored car glass. Oft times we would get into a “Tom and Jerry” chasing each other around a bush, firing at each other repeatedly 20 feet from one another without effect, before some photons would finally slide through a gap between the branches to lock the other guy out.

Also, with MILES, you were either fully functional, or dead. In reality, many people who are shot don’t stop fighting immediately. My limited experience with real gun battles is that there is a very messy period of dealing with the wounded afterward, something that rarely came up during our OA training.

When we went to the Volant Scorpion Airbase Ground Defense evaluation in Little Rock, the cadre would throw a casualty card on each person whose MILES gear had been locked out. Sometimes they were dead, but usually they required some kind of first aid. The biggest, heaviest guy on that deployment–his name, Swoboda, even sounded heavy–naturally was “neck injury, litter urgent.” We had to haul that massive guy back to our lines while fighting a running gun battle with the Aggressors.

Each of the three MILES components was powered by a single 9V battery–one in the laser transmitter, one in the MWLD harness, and one on the back of your helmet. 9Vs were feeble by modern standards, but at least they were easy to field test with a tongue, to see if they still had any juice.

If you wanted to, you could cheat with MILES by simply leaving the battery out of your harness. But what would be the fun in that? The fact that you could get shot is what made it so challenging. We were all in it for the challenge, to test ourselves, or we wouldn’t have tried out in the first place.

Surely, though, there was somebody somewhere who would be more interested in winning than in becoming harder to kill. Fortunately, there was an easy fix for that. Observer / Controllers could, and frequently did, test your system with their “god gun:” a laser transmitter with a pistol grip and a trigger. The god gun could also resurrect you by resetting your gear.

SMSgt Ferguson carried a god gun. He also carried a bullhorn. I called him, or should I say his amplified voice, “the Bullhorn god.”

Messages from the Bullhorn god

Sometimes, you would get a personal message from on high. If we were doing 3 – 5 second rushes (“I’m up, he sees me, I’m down”) and I let my feet fly up in the air when I plopped back down on my belly, the Bullhorn god said “Don’t get sloppy, George.” Yes, there is a right way to do it, and if your feet fly up like a flag, the bad guy sees just where you are. Or worse, the terrorist catches you in the ankles with the bullets you ducked as you went down.

Of course, the bullhorn was only for when he was far away. SMSgt Ferguson wasn’t afraid to get hands on if necessary. I’d be “low” crawling halfway between a low crawl and a high crawl, and SMSgt Ferguson would set me straight. Stepping on my helmet, he’d say “Low crawl means low.”

Some of you reading this might think that was a “dick” move, but I loved it. I’d expected that kind of training when I joined the military, but only rarely got it.

Besides, he was right.

If you weren’t bulldozing dirt with the down side of your helmet, you weren’t really low crawling. Which meant you were more likely to get that helmet–and its precious contents–perforated by bullets.

You don’t always, or even usually, have to low crawl. Most fights are in urban (or at least built-up) areas, and are up close.

Some soldiers at Ft Hood got shot in the back trying to crawl out of the processing center on 05 Nov 2009; they’d have moved much faster if they’d taken their chances on their feet (see Shooting and Scooting on Your Feet below). Their assailant stayed vertical, and practically stood over them.

My friend and fellow Border Patrol Agent (later Special Agent) Mike R took rifle fire near San Benito, TX. He was in the open, not far from a corn field. He defaulted to the training he got as a Marine Corps boot, and went prone, instead of staying on his feet and bolting for the concealment of the corn field. His assailant stayed on his feet, essentially giving him the “high ground” over Mike’s prostrate, slow moving low crawl. It very nearly cost Mike his life.

We call that tendency to do it the way you learned first or most, whether or not it’s the best thing to do in a given situation, “primacy of training” (as opposed to recency of training–the way you did it more recently). Infantry learn to go prone mostly to protect themselves from explosive threats. When a mortar hits the ground, it digs a little crater. The blast sends fragments and rocks up and out in a wide cone. If you’re low, that stuff might blow over you.

Low crawling might protect you from more distant grazing fire (as opposed to very distant plunging fire) if you’re in an irrigation ditch on the barren, windswept plains of Wyoming, or in a fallow Nebraska wheat field, near one of our ICBM launch facilities.

If you do need to low crawl, in needs to be low. SMSgt Ferguson made sure we understood that.

Time Pressure

Sometimes, the Bullhorn god would make a general public service announcement, like “Don’t bunch up!”

Or how much time you had left before you failed to achieve the objective.

Our exercises usually had a temporal limit. This was partially to make the best use of our day, but mainly to force us to think on our feet and solve problems under pressure.

For example, SMSgt Ferguson would say “You need to keep the Resource out of enemy hands for the next 20 minutes, starting,” (he’d play with his watch like a WWII bomber crew getting a time hack), “NOW.”

Or, “Bad guys have seized that LF,” referring to Uniform 1, the on-base launch facility. It contained an inert missile for the maintenance crews to practice on. “There is, or was, a maintenance crew on site, and the FSC (Flight Security Controller) has not heard from the SET (Security Escort) team since they reported being attacked 8 minutes ago. You have 32 minutes to regain control of the entire site, before the B-plug is all the way down, allowing access to the Resources.”

The 90th Strategic Missile Wing had plenty of those Resources. It was the most powerfully destructive combat unit in the history of man. We had three squadrons of Minuteman IIIs, each capable of carrying three MIRVs (multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles). The fourth squadron had Peacekeeper missiles, each capable of launching 10 MIRVs. Do the math:

The 90th Strategic Missile Wing had plenty of those Resources. It was the most powerfully destructive combat unit in the history of man. We had three squadrons of Minuteman IIIs, each capable of carrying three MIRVs (multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles). The fourth squadron had Peacekeeper missiles, each capable of launching 10 MIRVs. Do the math:

- Each squadron had five flights, which is to say, five launch control facilities (LCFs).

- Each LCF controlled 10 ICBMs, which meant 50 missiles per squadron.

- 3 squadrons of 50 missiles x 3 MIRVs each = 450 hydrogen bombs, plus the squadron of Peacekeepers with 500, meant that all day every day, and all night too, the “Mighty 90” had 950 thermonuclear devices ready to lay waste to our nation’s enemies, just about anywhere on the planet.

And that was just our wing. There were five other Minuteman ICBM wings.

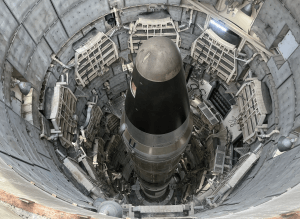

When I first joined SAC, there were still some Titan II missiles, with their single, massive W-53 warhead, on alert. The W-53 had a nine-megaton yield, “about three times the explosive force of all the bombs dropped during the Second World War, including both atomic bombs” (Schlosser, Command and Control, p. 3). The theory behind the W-53 was, if a Soviet command post is buried deep inside a mountain, and you level the mountain, you will neutralize the command post.

The Titans were liquid fueled. The fuel and oxidizer were each deadly poisons, but worst of all, they were hypergolic: they did not need a spark plug. If one molecule of Titan fuel contacted one molecule of the oxidizer, BOOM! Most of the early liquid fueled rockets were accidents waiting to happen. A Titan II blew up in its silo near Damascus, Arkansas on 19 Sep 1980. By 1987, all the Titans had been taken off alert. They were re-purposed as space launch vehicles after the Challenger disaster of 28 Jan 1986 temporarily grounded the space shuttles.

Minuteman and Peacekeeper ICBMs had more stable solid fuel, and there were roughly a thousand of them. Not to mention the Navy’s Boomers (SLBM launching subs), and Tomahawks.

AF GLCMs (ground-launched cruise missiles) and Army Pershing Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBMs) had really terrified Andropov and Gorbachev, so they were going away (see INF below).

Not all Priority A Resources were nuclear weapons; certain command and control facilities, such as Looking Glass, the airborne command post, and of course Air Force One, were as well. But all nukes, regardless of megatons or range, were Priority A Resources.

As the 90th Security Police Group Olympic Arena team, we were only interested in the 1, 3, or 10 Resources in our AOR–area of responsibly–that had, for exercise purposes, fallen (or were about to fall) into the wrong hands.

As the clock wound down, we would get reminders from the Bullhorn god.

“Ten minutes.”

“Five minutes.”

But the Bullhorn god’s most dreaded announcement was:

“Go get me some iron.”

Crow Creek had, over the eons, cut a small riparian valley across the middle of what would become FE Warren AFB. A set of railroad tracks ran along a bluff on the north side of that little valley. If we totally screwed up an exercise, we had to get SMSgt Ferguson some iron by running up the ridge, touching our rifle barrels to the tracks, and running back.

One time, we were a little lackadaisical about putting on our gear. Might’ve been a Monday. As I may have mentioned, SMSgt Ferguson didn’t like wasting a minute of our precious training time, so we spent the next hour or so practicing:

- Putting on our gear.

- Getting some iron.

- Taking off our gear.

- Repeating the previous three steps.

There may have been some pushups, that perennial character building tool, thrown in between steps 3 and 4 for good measure.

We always moved with a purpose after that.

To this day, when I catch myself dilly-dallying too long on any given task, I still hear the Bullhorn god’s voice, saying “Don’t make a career move out of it.”

SMSgt Ferguson was tough. The toughest I ever worked for.

“I don’t mind being called tough, since I find in this racket it’s the tough guys who lead the survivors.”

–Curtiss E. LeMay, the definitive SAC Warrior, when he led the 305th Bomb Group (from the front, in the lead B-17) during WWII

But SMSgt Ferguson was not some heartless bastard, although I must’ve thought so once or twice when we were doing wind sprints.

Far from it.

He cared more for us than just about every other leader I ever worked for, before or since. You could tell that by the way he looked out for us. The other way I knew he cared was when one of us got hurt.

Like most coaches, he was apt to tell you to “run it off” if you were in mild pain. Sometimes, one of us would get seriously injured (if it’s between you and a log on the O’ course, the log will win). SMSgt Ferguson usually maintained a tough exterior. He was far from humorless–he often made sardonic jokes and cracked a smile–but usually he wore a military leader’s poker face.

When Brad fell off an embankment during an exercise and broke his leg, though, Ferg looked like a little boy whose puppy had just been run over.

Positive Reinforcement

SMSgt Ferguson was a huge believer in positive reinforcement. There’s a common misperception out there, among trainers without a background in behavioral science, that “positive reinforcement” means some kind of yummy reward.

Not necessarily so.

In BF Skinner’s Operant Conditioning, “positive reinforcement” means something happens as an immediate and direct result of a behavior. For behaviors we want to encourage, it’s a good thing. But if the behavior is something we want to eliminate from our habits, the positive reinforcement can be a very unwanted consequence. (In contrast, negative reinforcement is when something does NOT happen as a result of your actions; it can be something you wanted to happen or something you dread.)

In BF Skinner’s Operant Conditioning, “positive reinforcement” means something happens as an immediate and direct result of a behavior. For behaviors we want to encourage, it’s a good thing. But if the behavior is something we want to eliminate from our habits, the positive reinforcement can be a very unwanted consequence. (In contrast, negative reinforcement is when something does NOT happen as a result of your actions; it can be something you wanted to happen or something you dread.)

SMSgt Ferguson’s positive reinforcement methods stay with me to this day. Even now, when I’m dry practicing, if I press the trigger a little too soon, before my sights are exactly where they need to be, or if I forget to wipe off the safety doing a left-side snap (presentation of the rifle from the left shoulder), I’ll drop for a few pushups. Not for the workout (which I can certainly use), but to program my brain not to do that.

Cardio is Key

We often trained on the obstacle course at Kirtland AFB in New Mexico. The O’ course was a few miles from our billets on the main base. Once, we ran through that O’ course late in the afternoon of the day before our weekly day off (the Lord rested on the seventh day, and so did we). SMSgt Ferguson loaded up our gear in the van, but not us. “See you topside,” he said, meaning back at the cantonment area of the main base. We could jog back or run back, but the sooner we got back, the sooner we could start our one-day weekend.

Running–fast–is one key to staying alive when bullets are flying. We ran often. The team would run 5Ks and 10Ks and participate in relay races around FE Warren’s gigantic Argonne Parade Field.

On occasion, SMSgt Ferguson drove us about 24 miles west of Warren AFB on Happy Jack Road, depositing us near the shore of the Granite Springs reservoir in Curt Gowdy State Park. Granite Springs Road, from the lake back up to Happy Jack Road, was about a mile long. It wasn’t particularly steep, but it was all uphill. We ran to the entrance, stretched, and got back in the van for the ride back to base.

Sometimes, we’d run out to and around the base lakes, which were on the north side of FE Warren.

Once, we were doing a formation run out to the lakes in all our gear (helmet, flak vest, LBE, magazines, ammo, rifle, gas mask, combat boots, etc). We were quite used to running in our gear. SMSgt Ferguson drove out there ahead of us in his pickup truck, and was waiting with his bullhorn when we got to the lakes. As we turned to go around the lakes, he raised the bullhorn to his lips.

“Gas, gas, gas.”

In the military, when a command is really important, you repeat it three times. “Eject! Eject! Eject!” or “Breach, breach, breach” (the latter meaning “bust the door in”).

“Gas, gas, gas” means there is a known or suspected (or, for training purposes, simulated) chemical contaminant in the air, so we had to don our M17 gas masks. Putting on the mask was a two-hand job, and it had to go on under your helmet, so we took turns handing off our helmets and rifles to the teammates next to us, while we ran, till we all had everything on.

Cheyenne, Wyoming is over a mile up, at 6000′ above sea level. The air was rare enough already. We were all quite accustomed to that as well. But then to draw what little there was through a mask filter as we ran felt like you were fighting for every single O2 molecule. (Three years later, when we were dodging Saddam’s nightly SCUD attacks in Saudi, I was grateful for every moment I’d had to grow accustomed to working out in that mask during the Ferguson Weight Loss Program.)

After we wound our way around the lakes, and turned the corner to run back to the main base, SMSgt Ferguson was still standing there.

“All clear,” spake the Bullhorn god.

In war, “All clear” is the signal meaning the electronic sniffers have tested the air. The litmus paper has not turned colors, and we cannot detect any lethal chemicals in the area. When the Bullhorn god said it, that meant we could take off our masks, a procedure requiring almost as much teamwork and coordination while running as putting the masks on had.

Only then, as we ran, it felt like somebody was standing over you with an air compressor forcing air into your lungs. Man, it felt good.

It was totally spontaneous. One of us sang out “Sooome tiiimes . . .” and everybody else automatically chimed in:

” . . . all I need is the air that I breathe . . .”

To me, at the time, it sounded better than the Hollies’ rendition which had been on the charts in ’74.

Afterward, SMSgt Ferguson told us the joke about a Marine who was beating his head against a brick wall. When his Gunny asked him why, he replied, “Because it feels so good when I stop.”

The Warbletones

Speaking of covers of hit songs, the 90th Strategic Missile Wing had an awesome missileer garage band named “the Warble Tones,” after a particular noise they might hear in the launch capsule. I’m guessing they did a lot of practicing down in that hole, because they were really good. Their cover of “Can’t You See” was, to my ears, better than Marshall Tucker’s.

When we were at the competition, at Vandenberg AFB in California, the Warble Tones could be heard some evenings at the Officer’s Club. They had a T-shirt, “Warble Tones World Tour ’89,” with the outlines of Wyoming, Nebraska, Colorado, and California on it.

The War Room

SMSgt Ferguson was not some mindless brute. Far from it. He studied military history voraciously.

I could listen to him talk about the Romans and their magnificent war machine for hours.

His father had fought in the Pacific during WWII, and left him two Japanese katanas. One still had the hilt, grip and pommel. The other had only the blade and the tang, the extension of the blade which would have fit into the handle, if it still had one. He wound up giving the latter to a friend. Subsequent research revealed that his complete sword was produced during WWII, but the one he gave away turned out to have been passed down through a Samurai family for hundreds of years (if I recall correctly, that one has since been returned to the Japanese family).

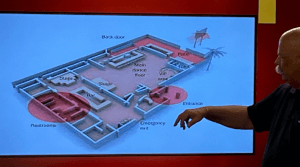

The Cop Shop, or headquarters, of the 90th Security Police Group was in building 34, the old base hospital built in the early 1900s. It was full of old Buffalo Soldier memorabilia from when Warren (as Ft DA Russell) had been a cavalry post. SMSgt Ferguson got us a room in the basement of the Cop Shop, just down the hall from the armory. It was our team’s ready room and headquarters. We called it the War Room.

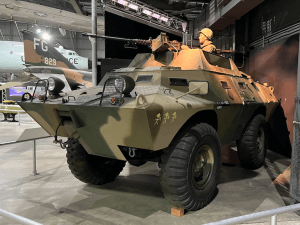

SMSgt Ferguson believed that a warrior must have an appreciation of terrain. The war room had a sand table–a wide, shallow, open topped wooden box at about waist level, full of sand, with toy soldiers, and toy tanks (we worked extensively with an armored car the USAF called a Peacekeeper; not to be confused with the MX “Peacekeeper” missile, or with SPs, who were often referred to in USAF literature as “Peacekeepers”). We used the sand table to plan, and to learn about how terrain affects our responses to situations.

Decades later, a former infantry / retired police officer named Brian K was running us through church security scenarios. The Army MOS, military occupational specialty designator, for basic infantry is 11B, pronounced “Eleven Bravo.” Or, in the gallows humor of a grunt, “eleven bullet stopper.” Brian usually had direct answers to students’ questions, but every once in a while, he would respond with a question.

“Do you want the cop answer, or the eleven bullet stopper answer?” Brian would ask. “A cop would say ‘It depends on the totality of circumstances.’ A grunt would say, ‘It depends on the situation and the terrain, sir‘.”

SMSgt Ferguson’s appreciation for terrain has stuck with me all these years. As a student and teacher of officer survival and personal protection, I often visit locations where gun battles have taken place. I’ve found I have a much better idea of what went on, and why, if I can just look at the ground it happened on (or sometimes, the room it happened in).

My wife calls it my “Morbid Tour of Death.” When possible, I interview the people who were there when things went down.

In the OA War Room, we watched VHS tapes of previous competitions, or military exercises, or real combat where such footage was available.

One audio recording SMSgt Ferguson played for his troops was of a USAF SP security controller in a bunker in Vietnam. The base was being attacked. He kept broadcasting and relaying instructions calmly, even when the VC could be heard beating on the door. Finally, as they breached the door, he said that all posts and patrols were no longer to receive instructions from that command center, as it had been overrun. I was told he was killed when he let go of the radio mike, took up his rifle or sidearm, and fought them at close quarters.

Modern students of weaponcraft don’t appreciate that the advent of the cell phone camera (and police dash / body cams) has given them exponentially more video of actual gun battles to learn from than we had back then.

We also trained on radios, security checklist procedures, practiced handcuffing, and got briefings from various subject matter experts. SMSgt Ferguson himself would often lead the lecture. We were encouraged to pipe in with our own perspectives on lessons learned, or better ways to do things.

From notes I took on 30 Jan 1989, entitled “Ferg on . . . NCO duties vis-a-vis Leadership, Followership, and Teamship:”

Leadership

- If in charge, be in charge

- Take the initiative

- If you make a mistake [in my notes it was written “step on your dick,” but I’m that was my own shorthand, rather than verbatim from SMSgt Ferguson’s lecture], admit it

- Trust

- Always do your best, and set the example [here, in my notes, I referenced a Rommel quote below, that I’d learned as a Doolie at the Air Force Academy; it was my favorite of all the aphorisms on leadership we’d had to memorize]

- Always look for the better way [here, I referenced another SMSgt, Gerald A. Norton, who’d done his best to mold me into something Uncle Sam could use; he always told us to Work smarter, not harder. I also referenced the “First Rule of Fencing” I’d learned from my USAFA Fencing coach: If it doesn’t work, try something else.]

- Don’t be afraid to correct.

“Be an example to your men, in your duty and in private life. Never spare yourself, and let the troops see that you don’t, in your endurance of fatigue and privation. Always be tactful and well mannered, and teach your subordinates to be the same. Avoid excessive sharpness or harshness of voice, which usually indicates the man who has shortcomings of his own to hide.“

–Field Marshall Erwin Rommel

Followership

- When the exercise is underway, do what [you are] told; save debate for later.

- If you know something has to be done, do it–don’t wait till later. [Decades afterward, when I was training with our SRT (SWAT) team, we called that “Initiative Based Tactics“–asking yourself what needs to be done, but isn’t being done yet, and doing it.]

Teamship

- The team is everything.

- The team has / will develop its own personality; [but] it is NOT a democracy. [These days, we call that personality an “organizational culture“]

- Win or nothing.

That last wasn’t just for the Olympic Arena competition, and it wan’t just Alpha Male competitiveness. It’s a common theme in the military, where the fate of your troops, or perhaps even your nation, hangs in the balance.

When I went through Basic Cadet Training (abbreviated BCT, but pronounced “Beast”) in Colorado Springs, there were 10 squadrons. I was in Alpha squadron. There were numerous metrics by which they graded all the squadrons, “racking and stacking” them from best to worst every week. Alpha, nicknamed “Aggressors,” took an early lead, earning honors for best squadron several weeks in a row.

Then, one week, we took second place. I didn’t think second out of ten squadrons was too bad.

Boy, was I wrong.

Our cadre chewed us out for an hour. “There is no ‘second place’ in the Fulda Gap. Do you understand?!?“

The Fulda Gap, for those of you youngsters who never heard of it, is a German plain, prime tank terrain through which the Soviet armored spearhead was expected to thrust into West Germany.

“The conventional war scenario in Western Europe revolves around Warsaw Pact armored formations. Outnumbered and outgunned on the ground, NATO must stem a communist advance with tactical airpower: airplanes and helos equipped to kill tanks. In the midst of a continuing battle for general air superiority, tactical aircraft will fight at low level, drawn to battle by the approach of enemy armor. Toss in mobile flak and SAM batteries, plus shoulder-mounted antiaircraft weapons, and you’re in for a real slugfest: high intensity, short duration, extremely lethal.“

–A Barrett Tillman quote I wrote down in 1984

The same principle applies to you, in your personal protection journey. Bill Jordan, a famed Border Patrol pistolero of the 1950s and 60s, wrote a classic book every serious defensive handgunner should read, called No Second Place Winner.

The Wisdom of the Saints

SMSgt Ferguson was huge on military aphorisms. Apart from maps, the walls of the war room were decorated with framed quotes by generals such as Patton, and theorists like Sun Tsu and Clausewitz.

Ferg had a sense of humor, too. One of the quotes was

“War, children, is just a shot away. It’s just a shot away.“

–Mick Jagger and Keith Richards

We actually had a hard time driving nails into the walls of the War Room. Turned out they were lined with lead; it had been the hospital X-ray room back in the day.

Was OA Worth It?

Olympic Arena wasn’t just about raising morale, although, as team members, we were authorized to wear the Missile Comp patch on our uniforms thereafter. I was personally quite proud of my time on the teams (and still am, in case you haven’t noticed).

Nor was OA just an excuse for colonels to get together with colonels from other bases that they’d been stationed together with as lieutenants–although that did happen. There was a great deal of revelry, fanfare, and team building with other bases at Missile Comp.

It was also there to build a sense of community and teamwork throughout the ICBM force. We each started with a number of hat pins from our own base; in the evenings during the comp there was a brisk hat pin trade between SAC warriors from the different bases.

Acceptable Losses

We were all expendable pawns.

The first time I’d been shot during a MILES exercise was only a few seconds into an ambush, during RECONDO training in ’83. I never saw the guy that got me (they were all guys, then). I sat on my helmet and contemplated the loss. I have only one life to lose, and it can be over that quick. I took death seriously, one might even say deadly seriously, for someone my age.

During a tabletop Command and Control exercise my sophomore year the Air Force Academy, I’d chosen to send an A-10 to attack a pair of T-72 tanks that were about to overrun an American platoon, instead of having the A-10 first clear the way by taking out a mobile ZSU-23/4 antiaircraft cannon that had rolled into our battle space.

They rolled the dice. The A-10 got shot down.

I had to draft a letter of condolence to the fictional A-10 pilot’s fictional wife. That forced me to think about the responsibilities of combat leadership.

The captain running the exercise explained that my intentions of rescuing the hard-pressed platoon with CAS (close air support) may have been noble, but I wasn’t just gambling with another man’s life by not waiting to secure a safe environment for our birds to fly over. Not only were the A-10 pilot’s kid’s going to grow up fatherless, but now our side was down one more precious aircraft, and a very hard to replace pilot, for the duration. And all the platoons they might have rescued in the future were going to suffer for it.

In war, command decisions can have tsunami-sized ripples.

But OA, years later, was not a real conflict. It was a competition. The worse that would happen was that some colonel might not get to put the Blanchard trophy in his office. If the time allotted for the exercise was winding down, one might get in the habit of using his troops, including himself, as pawns, sacrificial lambs, as diversions, so one of the other teammates could re-secure the Resource. It was more realistic, and far more complicated, than “capture the flag” played by boy scouts, but not entirely unlike it.

While I never thought of my troops as expendable during subsequent wartime deployments, I do remember running down a road that real rifle bullets had just bounced off of, during a gun battle in South Texas. I was thinking, quite clearly, This is stupid. We’re not doing 3 – 5 second rushes. I expected to get shot at any second.

The real bullets did not deter me, even though I knew better than to do it the way we were doing it. Our people in the kill zone needed help, and we were racing there as fast as we could. I’d been shot so many hundreds (perhaps even thousands) of times by MILES lasers, getting shot at no longer concerned me all that much.

Don’t get me wrong: I was, in fact, concerned. I would even go so far as to say the situation had my undivided attention. But SMSgt Ferguson (and many others) had trained me to respond to ambush so many times before, I was not terrified to the point of inaction. Because of my training, I was able to do my job.

In 2023, I spoke with a volunteer EMT who had run out to assist when a pickup truck crashed into a concrete ditch across the street from her business. She and her coworkers were driven back into their building when the driver pulled out an AR and began shooting at them.

“No amount of training can prepare you for that,” she said.

My heart was heavy for her and the predicament she found herself in, but I’m not sure I agree with that supposition. I’d heard such statements before. They are usually made by the untrained, or those with minimal training, or by those who were trained, but not for the situation they found themselves in (specifically, sudden violent assault). It’s likely that as an EMT, she had never trained to respond to being ambushed by one of her patients.

The effectiveness of training, I think, depends on the type, quality, and quantity of your training.

Time and again I have seen and personally experienced incidents of trained people, myself included, following their training to the letter (for good or ill) in emergencies. SMSgt Ferguson trained us a lot, and well, for the specific missions we were to perform.

Disparity of Resource Allotment

The time, treasure (read that ammo) and effort they invested in training a dozen, about 1%, of our group’s 1100 cops for the Olympic Arena competitions might have been spread around more. The disparity became embarrassingly obvious when some (not even all) of our team were tasked with being Aggressors (sort of like Richard Marcinco’s Red Cell) for a WSA Response Force (RF) / Quick Reaction Force (QRF) exercise.

The WSA was the base’s nuclear weapons storage area. It had a fairly robust Response Force on hand, with vehicle mounted patrols outside and inside the wire, a sensor operator in a centrally located tower, a manned, hardened entry control point, and two fire teams protected in a hardened facility, capable of sallying forth in armored vehicles with machine guns and grenade launchers.

Other cops on base could be called upon to respond as a mobile reserve, or QRF.

During the exercise, it took the handful of OA competitors only a few minutes to wipe out virtually the entire WSA RF, and the QRF.

Were the OA OpFor superheroes with magical powers? No. They had simply trained for combat, hard, 6 days a week, for half a year. And they’d been taught by the best.

Here’s how they did it.

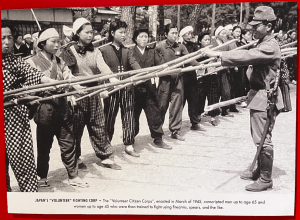

SMSgt Ferguson had studied, and learned from, USAF bases that had been attacked in the previous war (Vietnam). At Bien Hoa, for example, the Charlies rocked a USAF bunker mercilessly with Rocket Propelled Grenades. The shaped charges of RPG rounds were big and bulky, like a diamond on a stick, and a grenadier could only carry so many. Heavily seeped in Communist doctrine, the Viet Cong (and their North Vietnamese Army allies) believed in sharing everything. They would have one soldier (or more) with an RPG firing tube. Every other soldier in the outfit would carry two Rocket Propelled Grenades. As they pressed forward toward the wire to form the sapper / assault team, they would walk past the RPG grenadier’s position, and drop off grenades for the grenadier to fire. He wound up with a whole pile of them, enabling him to fire continuously, in rapid succession, throughout the assault.

Two decades later, in Wyoming, the OpFor were given a limited number of blanks for the exercise, partially to conserve resources, but also to stack the odds in favor of the WSA Response Force. SMSgt Ferguson directed one OpFor Aggressor to be the Designated Distractor. The Distractor bunkered down somewhere bullet (and photon) resistant, like a culvert. Every member of the ambush / assault teams donated one of their own magazines to the distractor, so he wound up with a pile of mags to keep him in business.

Then the OpFor assault teams, knowing how the response force would deploy–they, too, were SPs–set up ambushes along routes we knew the WSA RF would take.

When the exercise kicked off, the Designated Distractor opened fire on the WSA–specifically, on Alarm Response Teams (ARTs) that rove around the interior, and the Security Response Team (SRT) that patrolled outside the wire. With all his extra magazines, the Distractor was able to keep up a steady volume of fire.

In accordance with their general orders, the SRT and ARTs

- Detected the Attack, and

- Sounded the Alarm.

They were mostly taken out before they could get to step 3, Reacting to Defend.

Which was to be expected.

ARTs and SRTs were in “soft” vehicles. They spent most of their day-to-day lives doing mundane tasks like running chow to / from the Entry Control Point (ECP), or relieving troops who smoked so they could step outside the gate and take a cigarette break (the WSA was a smoke free area). Sounding the Alarm was step 2, not step 3, because they were not guaranteed to live long enough to do all three, and getting the cavalry on the way was far more important than any effect their own small arms would have on the outcome of a determined, pre-planned assault on the WSA.

Hearing the SRT and ARTs’ cries for help (and the approximate location of the Designated Distractor), the Alert Fire Teams (AFTs) sallied forth from their hardened AFT Facility, in their bullet-resistant Peacekeeper (“PK”) armored cars. All except for the M60 machine gunners, who, in accordance with standard doctrine, were sticking their soft bodies (in flak vests and PASGT helmets) up out of the top hatches.

The gunners hanging out of the turrets soon located the Designated Distractor. His whole mission in life, after all, was to be seen and heard. As they prepared to rock his world with their machine guns, the gunners in the turrets were drilled through the ears–or should I say through the MILES on their helmets.

OpFor assault teams had set themselves up perpendicular to the route the Fire Teams would inevitably take to engage the Designated Distractor. Since the top hatches of the PK armored cars had zero side protection, taking out the M60 gunners was easy, and almost inevitable (see Tactics Laboratory, Lesson 1, below).

The WSA Fire Teams had not spent hours and hours learning how to dismount the PK in a matter of seconds, closing the armored doors behind them, as we had (Tactics Lab Lesson 3 below). And instead of using the armored vehicle as a vehicle or mobile bunker, staying buttoned up and firing from the ports, they got out. Dismounted infantry support is essential, but when they did, they did not obey the Antelope Principle of always having one person assigned to watch their back, and left the rear doors open. The OpFor easily wiped them out with fire from the sides and rear quarters.

There were still 2 – 4 Security Policemen (that term includes women) from the WSA RF left alive:

- If s/he stayed low, the Alarm Monitor in the hardened control tower could avoid the MILES laser photons that would pass through the windows.

- The Entry Controller, in the hardened Entry Control Point, was safe because, like the SPs of the RF, the OpFor was the lightest of light infantry; they had no LAW rockets, mortars, or RPGs. The HEDP (High Explosive Dual Purpose) rounds carried by the M203 gunners of both sides might penetrate the walls of the ECP, but for safety reasons, the Air Force wouldn’t let us shoot even talcum powder filled practice grenades at each other during force-on-force exercises.

- If the Searcher who worked in the Entrapment Area (search pit) adjacent to the ECP was smart enough to bunker down or fall back into the ECP at the onset, she or he might not have been hearing the irritating noise of their locked-out MILES harness.

- The RF had a flight sergeant / RF leader, who usually spent most of his time in his office within the ECP, writing the next week’s duty assignments. I’m not sure where he led from during the exercise. If he chose to use the ECP as a command bunker, he could very well have still been alive. I’m guessing that, knowing the exercise was imminent, he chose instead to be doing a “post check” up in the Alarm Monitor’s control tower, which would have afforded him a commanding view of the situation.

Don’t lose sleep over the “fallen” members of the RF. Even if terrorists had wiped out the RF completely, the bad guys would not have had automatic access to the nukes. There were three concentric rings of hurricane fence and concertina wire surrounding the WSA. The buildings in which the nukes were stored were hardened, locked tight, and manned by maintenance troops with shotguns.

Besides, help–the QRF–was on the way.

In real life, it could take an hour or more to spool up a QRF manned by “back office” Building 34 personnel and younger, single sky cops who lived in the converted cavalry barracks on base. For this exercise, the QRF was already spun up, armed up, and jocked up in flak vests, helmets, and MILES gear, waiting at a staging location for the scheduled assault on the WSA.

SMSgt Ferguson had given us guiding principles, rather than rigid doctrine. One of those principles was to “Defend the resource away from the resource.” We weren’t linemen defending a quarterback in football. We had small arms that could reach across hundreds of meters. Instead of “shielding,” which would only draw fire toward those precious resources we were trying to protect, we chose to dominate the terrain around the resource, denying opponents the chance to approach it (see Lesson 2, Ambush Response: Blocking Rather Than Shielding below).

As OpFor, the OA team used those same principles to deny the QRF access to the WSA.

I wasn’t there for that one, and I don’t know if the QRF also went after the Designated Distractor, or if, since most of the RF were out of action, the QRF felt it was their duty to “repopulate” the WSA.

The ECP was designed to limit access and channelize the approach of suicide bombers with VBIEDs (vehicle borne improvised explosive devices). Trying to get into a storage area designed to keep people out would be time consuming, and mobility limiting, at best.

Whether the QRF chose the latter, the former, or to split their forces and attempt both, the OpFor did them even dirtier.

After easily taking out the M60 gunners in the top hatches, the OA OpFor “swarmed” the QRF’s Peacekeeper Armored cars. When enemy troops are too close for those inside to see or shoot them through the firing ports, they are in what we call “dead space,” and cannot be engaged (except by running them over). But they can stick their own muzzles in through any open firing ports and do a number on anyone inside (Lesson 3 below).

The QRF was destroyed, to a man.

Some of the 90th SPG leadership had been watching the exercise, and those who were not immediately responded to preside over the disastrous aftermath. SMSgt Ferguson could see it was not going to be a high point in the career of MSgt Brubaker, who had led those defending the WSA (which was too bad; I had worked for Brubaker, and he was a good, hard working guy). SMSgt Ferguson ordered the OA OpFor not to gloat or to high-five. Instead, they were to gather up their gear, act like quiet professionals, and RTB–return to Building 34.

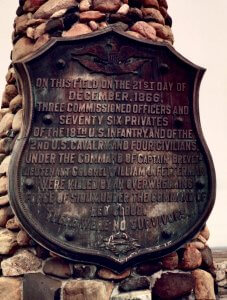

The lessons of that day were not new. A century before, on 21 Dec 1866, in that Wyoming territory, Red Cloud chose representatives of the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Lakota to act as Designated Distractors, luring Capt Fetterman and his troops away from the support of Fort Phil Kearny, and into an ambush that wiped them out to a man.

Nor did it end there. A few short years after that WSA exercise, Russian armored columns were devastated in the close confines of Grozny.

But saddest of all was that no member of the OpFor was ever, to my knowledge, asked what tactics enabled them to accomplish such a feat, and how the WSA RFs / QRFs could adapt to prevent such a disastrous occurrence in real life.

Tactics Laboratory and Dissemination of Lessons Learned

Ostensibly, Missile Comp was supposed to be a laboratory for testing new and better ways to accomplish our mission. For the cops, that meant small unit tactics. The OA competitors would then return to each of the squadrons they’d been drawn from, and (theoretically, at least) put those lessons learned into action.

In that, we had mixed results. Here are some examples of things we figured out through the trial and error of constant force on force training, and the ways those lessons were shared with the rest of our career field (or not):

1) Exposed Turrets are Deathtraps

We learned early on that an M60 machine gunner in the turret of a Peacekeeper armored car might be fine below the rib cage, but the rest of him or her was going to look like Swiss cheese within seconds of enemy contact. The turret had some cover in front, and a little from the hatch in back, but in the real world threats are all the way around, and the gunner is really exposed from the sides.

Not only was the gunner going to have a closed-casket funeral, but (perhaps more importantly), we were then going to be down our most powerful and intimidating weapon. Not to mention losing the use of the assistant gunner, who in real life would be trying to patch the gunner’s holes, or getting shot himself trying to take over the gunner’s job.

After OA, when I went to the WSA as a fire team leader, I had my machine gunners place their “hogs” in racks inside the Peacekeeper armored cars, rather than in the pintle mount on top. I figured if the bad guys were really far away, in only one direction, it would be easier to put it up there than it would be to pull the gun (and the gunner’s brains) out of the turret, if that were not the case.

My plan, instead, was to use the armored vehicle as a bullet resistant taxi, to get the gunner and his or her assistant to a useful position of cover (we had bunkers at various points around the WSA). I got that plan directly from the endless hours SMSgt Ferguson had us working with the Peacekeeper. It became our flight’s standard practice in the WSA for short while.

Then, one day when I wasn’t there to explain why, a new group commander inspected the WSA’s Alert Fire Team Facility and was unimpressed that the guns were not up in the turrets. Back up they went.

Something similar occurred when I went to Saudi for Ops Desert Shield and Storm. We did just fine when we were only a few rapidly deployable flights of 44 SPs. But eventually, as we became a group (the 1703 Ground Defense Force, Provisional) a “command element” arrived and took over.

Command insisted that the M60s be in the turrets of our unarmored Hummers. I brought up our OA experience, that practically every single time the gunner stuck his head up out of that turret he got it shot off, to my chain of command. They listened patiently and then directed me to put the gun up there anyway. I did, but then instructed “T Bone,” my M60 gunner, not to go up there and use it unless I specifically ordered him to. T Bone was to grab our compliment of LAW rockets instead.

I think part of the reason the command types liked the guns up in the turrets was because it looks bad-ass. Let’s face it: security is more about looking prepared (for deterrence) than it is about being prepared (for fighting).

Also, a gunner (or tank commander) who sticks their head up & out of that turret has far better situational awareness they can pass on to their buttoned up crew mates (that is, for as long as they are alive).

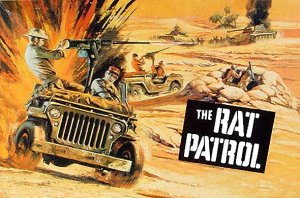

But the main reason, I think–and perhaps I’m being cynical here–is that the commanders of the 1980s had grown up watching The Rat Patrol.

We didn’t pay in blood to ignore those lessons about turrets lacking wrap-around protection till Afghanistan and Iraq. Then we paid quite heavily to relearn them. By then most of the guys I’d learned them with had retired.

In Ops Enduring and Iraqi Freedom, body armor had improved from mere fragment protection (the flak vests we wore in the 1980s) to the Interceptor vest, which could stop real (pistol) bullets. The heavy ceramic plates of the Interceptor could stop rifle bullets fired from directly in front or behind, but were useless for rifle threats from the flanks.

2) Ambush Response: Blocking Rather Than Shielding

If you are reading this, you are probably a Protector.

If you and your loved one(s) get accosted by a mugger with a gun on your way home tonight, your natural inclination, as a Protector, may be to say “Get behind me!”

That instinct–and it is an instinct–is hard-wired into Protectors. As with breathing, the system is issued with that firmware already installed. The instinct to put our loved ones behind us was programmed into our genetic memory when the threats we faced were fangs, claws, and sharp sticks.

But think about that.

Bullets, which have only been around for about 500 years, may or may not go through you. If you get into any sort of ballistic exchange, putting your loved ones behind you only serves to draw fire toward them.

You’d probably improve their odds if you have them get away from you, while you do whatever it takes to gain and keep the bad guy’s undivided attention.

We came to a similar conclusion, on a slightly larger scale, during Missile Comp.

The scenario for one of our OA tactics exercises (during the competition, at Vandenberg) was a nuclear convoy under attack.

MIRVs need to be swapped out, inspected, and maintained periodically. When a nuke went from the WSA to a launch site, or back, it was loaded into a tractor-trailer rig called a PT (Payload Transporter) van.

The PT van was very similar the 18 wheelers you see shuttling goods around on the highways, except that the tractor was painted dark Air Force blue, and the outside of the trailer had trapezoidal skirts to fold down over the open top of the silo.

To swap out a warhead, they would drive the PT van across the top of the launcher (the massive, polygonal concrete door could easily handle the weight of the tractor trailer rig). With the wheels parked on either side, and the skirts let down to cover the opening (for privacy from Soviet spy satellites), they would pull the door out from under the semi-trailer, which had trap doors on the bottom. They would lift the nose cone off the missile with a hoist inside the trailer, and swap out the MIRVs, the “payload” of the missile (hence the term, “payload transporter”).

Several vehicles escorted the PT van.

The convoy commander sometimes rode in his own vehicle, and sometimes rode with the deputy US marshal.

The marshal’s job was to run interference with the local populace, if necessary. The SPs had zero law enforcement authority off base, but somewhat god-like jurisdiction wherever the nuke was. Deputy USMs, of course, have law enforcement authority that is generally recognized throughout these United States and its territories.

There was a scout vehicle miles ahead of the convoy, looking for trouble, and a trail vehicle miles behind. Theoretically, the trail vehicle would be too far back to be caught in the kill zone of a convoy ambush. They could then direct responses and could flank any ambushers, like Brian Chontosh later did in Iraq.

There was an armed fire team in a helicopter escorting the convoy They kept an eye on things from above, and could be set down wherever the convoy commander needed them most (Dave Gordon, one of my squadron mates from the AF Academy, was killed, along with his right seater and 3/4 of the SPs in the Airborne Fire Team, when their Huey crashed escorting a nuclear convoy out of Ellsworth AFB on 29 May 1986).

Fire teams in armored Peacekeepers rode immediately in front of and behind the PT van.

If you are ever ambushed in a vehicle, your best bet will probably be pressing firmly upon the right hand pedal, to exit the kill zone of the ambush as soon as you can.

If your unarmored vehicle becomes incapacitated in an ambush–if it no longer moves–your best bet is to get out of and away from that flak magnet as soon as you can.

In 2012, after one of our special agents was killed, and another wounded, during a roadblock ambush in Mexico, my agency convened a conference of law enforcement firearms instructors to study ambush response. We hired the Tier 1 Spec Ops operators of JTM to advise us. They called a non-moving, unarmored vehicle a “death box.”

I’ve seen civilian law enforcement vehicles that looked like Swiss cheese after cops were ambushed. A ’72 Pontiac might be somewhat resistant to gunfire–the voice of personal experience speaks here, as well–but modern plastic bodied cars, not so much.

On 18 July 2020, a trucker used his 18-wheeler in a 3-hour Mad Max rampage in Ohio. He was driving the wrong way, westbound on the eastbound side of I-275, when a Cincinnati PD SWAT sniper took out his engine with a .50 caliber BMG round.

That’s one way to stop an 18 wheeler. As SPs in Peacekeeper armored cars, running nuclear convoys, we were more concerned with being stopped ourselves. Rifles chambered for the .50 BMG round were few and far between in the ’80s. We figured the bad guys would use stolen LAW rockets, or smuggled RPGs, or perhaps a stolen M2 heavy machine gun to take out our armored cars.