Primacy vs Recency of Training

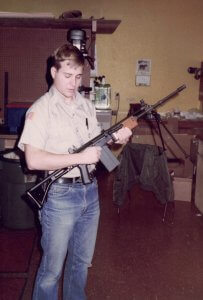

Jason, our assistant machine gunner (standing on Humvee), and grenadier “Jethro,” with his load bearing vest full of 40mm high explosive, ham it up by one of our KC-135s at King Khalid International Airport, during Operation Desert Shield.

Part I:

The Problem

“Any idea what’s going on?” I asked the crew chief. He had almost jumped out of his skin when I walked up behind him and tapped him on the shoulder.

“What the f__k do you think is going on?” he screamed.

He would have screamed, even if he wasn’t on edge, which he clearly was.

He had to yell to be heard over the massive jet noise.

Almost every engine in the world’s largest airborne tanker unit, the 1703rd Aerial Refueling Wing (provisional), was spooling up. Us security treads weren’t in the loop, but we knew something was up, because it was the middle of the night, and bread trucks (crew vans) had come racing up to all the planes. Crews sprinted to the birds, climbed inside, and were cranking them on.

Our KC-135s (Boeing 707s built as flying gas tanks) had been parked, nose to tail, down the side of a taxiway at King Khalid International Airport (KKIA), in Saudi Arabia. Now, they were all “elephant walking,” one behind the other, to the end of the runway which ran parallel to the taxiway, and roaring past us into the night sky.

It was during Operation Desert Shield, the buildup to Desert Storm. Our primary mission at that time was to keep Saddam Hussein’s army from driving south into Saudi. When we got enough manpower and materiel on hand, we would set about evicting the Iraqi squatters from Kuwait.

The Iraqis often made a show of force, or tested our responses, by flying their Mirage and MiG fighters toward the Saudi border. Every time they did, we sent up our fighters to make sure they stayed in their own airspace. The Iraqi AF peeled off when they were painted by the radars in our fighters.

The Israelis had done something similar before their tactically brilliant preemptive strikes on the Egyptian Air Forces that kicked off the Six-Day War. They had flown an air patrol over the Mediterranean, north of Egypt, first thing each morning, for about two years. The Egyptian Air Force responded in kind, every day. Eventually it became a boring routine. The IAF would then go home, dropping off Arab radars as they approached to land. Then the Egyptians would land and drink their morning chai while being refueled.

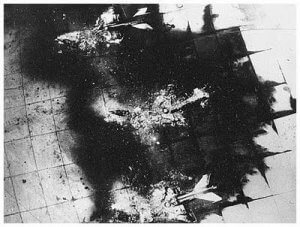

On the morning of 05 Jun 1967, a larger than normal number of IAF aircraft flew out over the Med. As usual, they dropped below radar after flying routine patrol routes. But after losing altitude, instead of landing, they changed course flew toward Egypt at 60 feet above sea level. While the Egyptian pilots were drinking their tea, the IAF flew over and cratered their runways, trapping their planes on the ground. Their strikes were precisely timed and nearly simultaneous.

The IAF spent the rest of the day destroying grounded Egyptian, Syrian, Jordanian, and Iraqi aircraft (which, combined, outnumbered IAF aircraft 3 to 1) from the air.

On 22 Sep 1980, Saddam Hussein had kicked off his invasion of Iran with airstrikes on a dozen Iranian airfields, clearly modeled on (though far less perfectly executed than) Israel’s 1967 air raids.

As I stood on the ramp at KKIA, north of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 10 years later, the Iraqis had used more planes than their usual air patrols, and flew in complete radio silence, an ominous change from their normal routine. Suspecting a possible pre-emptive strike, Central Command scrambled just about everything we had that would fly.

The 1703rd ground crewman I’d plied for information got interrupted by the aircrew in his headset, and went back to the business of getting his KC-135 launched.

BDOC (Base Defense Operations Center) got on the horn and told our grenadiers to upload 40mm into their M-203 grenade launchers. That’s when I knew things were serious. We carried loaded magazines in our rifles whenever we were on post, but we never put live grenades in the ‘203s, except on the range. And those were the blue practice rounds filled with orange talcum powder. Now we were uploading high explosive dual purpose (HEDP) armor piercing grenades.

Difficult to guess what was going through the mind of that megalomaniac (who wound up converting valuable oxygen into CO2 a lot longer than he should have), but for reasons that made sense to him, Saddam decided not to try us on that evening. Eventually, our birds came back to roost, although after that we may have upped the number that were patrolling the skies near at any given time.

About sunrise, when the war had still not commenced (it would not, till the following January), BDOC told us to download the ‘203s.

A grenadier named Chris, whom we all called “Jethro” (as in “Jethro Bodine” the Beverly Hillbilly) opened up his M203, without sticking his hand underneath to catch the extracted round.

He dropped a live HEDP grenade on the concrete right behind Jason, our driver and assistant M60 gunner.

The grenade hit the ground hard enough to dent the ogive (the rounded front). EOD (explosive ordnance disposal) troops had to make it go away.

‘Thro had been victimized by his Primacy of Training.

Primacy of Training

Primacy of Training can be good or bad, but more often than not, it’s the latter.

Simply put,

PRIMACY describes the methods you learned first, or have practiced the most, or both.

Recency of Training

In contrast, RECENCY, as one might expect, is how you did it the last time (or the last few times) you tried it.

Right after you learn to do something a different way, or learn to operate a different weapons system, the new method will stick in your short term memory. But until we’ve practiced that method more than we practiced the first, or worked with that new weapon more than we worked with the old one, or if it’s simply been too long since our most recent Recency, we often revert to our old ways under stress.

I believe it has to do with how our neural pathways are established. When we first learn something completely different–driving a car, for example–the methods are inscribed on a blank slate. A brand-new file folder is created, and stuck in the filing cabinet of our brain, if you will. Different variations on that theme (driving in snow, for example) become subroutines of that program, more papers stuffed in the same folder.

Example 1: Stick vs Automatic

I learned to drive on my parents’ manual transmission (“stick-shift”) cars.

With a stick shift, as most of us old geezers know, there are three foot pedals. The one on the right, familiar to all of us who drive, is the accelerator (the gas pedal; the car’s equivalent of an airplane’s throttle)–just the same as with an automatic transmission. The one in the middle is the brake. The brake pedal is in more or less the same place as the brake on a 2-pedal automatic. Usually the brake of a stick shift car is narrower, to make room for the third pedal.

The far left of the three foot pedals is the clutch, which when pushed down disconnects the transmission from the engine, so you can shift gears smoothly.

You work your way up through the gears while accelerating. You can also work your way down though the gears while decelerating, though it’s not required. Down (or up) shifting gives you much more direct input, and conceivably better control, as each gear prefers a certain speed range. You can even use the engine to slow the car, a process called “engine braking,” although it is not required (and not permitted for big diesel rigs in certain areas, to reduce engine noise). Engine braking puts more wear and tear on your engine, and less on your brakes (which are easier and cheaper to replace), but you might want to stay in a lower gear coming down a steep mountain road, since doing that puts less wear and tear on the engine than ramming into a guardrail or flying off a cliff would.

The general rule with that clutch pedal is “Down fast, up slow.” Sort of like we get our pistol out of the holster fast, but then slow down on the trigger as necessary.

“Riding” the left hand pedal half way up causes slippage (and thus wear) of something we called the clutch plate (the interface between the engine and the transmission), but just hopping off the clutch pedal causes the car to lurch, so you rolled off of the clutch smoothly–like a trigger press. But you always came down on the clutch fast, so as not to unnecessarily wear that clutch plate.

All of which sets the stage to say that as you approach an intersection with a light that turns red, in a stick-shift car, one might correctly get into the habit of slamming one’s foot down on the left hand pedal quickly, and coasting to a stop, braking as necessary.

For me, that habit was formed by Primacy of Training. It was what I learned first in my parents’ cars, and until I bought a car of my own, it was the way I had driven the most.

When I was a starving college student, 4 of my friends and I each pitched in $120 and bought an old beater. It had rolled off a GM assembly line in the early 1970s. That big hunk of Detroit iron had an automatic transmission.

Because there was no need to make room for a non-existent clutch pedal, the brake pedal was extra wide. The Detroit engineers wouldn’t want any drivers to miss the brake in an emergency.

Most of the time, at first, I did just fine with the automatic transmission. It is, after all, simpler to operate. Requisite habits for driving an automatic became my Recency of Training (the way I had done it most recently).

But sometimes, when I came up to a light that just turned red, I would slam my left food down on the clutch that wasn’t there, hitting the brake instead.

That’s Primacy of Training.

I don’t do that any more. I’ve been driving automatics (mostly G-rides) almost exclusively for decades now. Since then, my Recency of driving automatics has overtaken my Primacy of subconscious habits for driving a stick-shift. Indeed, I’ve driven automatics so often, methods for driving automatics have become my (newer) Primacy of Training, the habits I revert to under stress–even on those rare occasions when I’m driving a stick.

Example 2: Different Weapons Systems

As with different makes and models of cars, the levers and controls and even the way different pistols operate can vary. Sometimes enough to require a different manual of arms.

My first two duty handguns were revolvers (both 4″ Smith and Wessons: the Model 15 and the 586). My first semi-auto duty pistol was the M1911A1. I carried it at work when I was a range officer at a civilian firing range from ’84 to ’86. It was my off-duty pistol after that.

As most of you know, that venerable GI .45 has an external manual safety. I carried it in Condition 1, “cocked ‘n’ locked,” with the hammer back and the external manual safety up / on, as I believe John Moses Browning designed it to be carried (see Alert Carry Conditions for more info).

I practiced presentations, getting that M1911A1 out of the holster and into action, as often as possible. I thumbed down the safety as I was pushing the pistol to arm extension.

From the mid-’80s to the mid-’90s, that M1911A1 was my “go-to” pistol, the one I carried and practiced with the most.

After I made the manual of arms for that GI .45 habitual, the number of times I forgot to press the thumb safety off / down during the presentation (out of literally thousands of “reps,” according to my shooting practice logs for that time period), could be counted on one hand. When I did, I would drop for some pushups, to reinforce not forgetting it (see Getting Iron for the Bullhorn God to learn more about positive and negative reinforcement in small arms / tactical training).

Starting in the mid 1990s, I carried a series of other duty pistols on a daily basis. In chronological order, they were:

- Ruger P94DAO in .40

- Glock 19 in 9mm

- Beretta 96D in .40

- Heckler & Koch USP-C in .40

- SIG P229 DAK in .40

- Glock 17, 19, and 26 in 9mm

When I was in uniform, whenever possible, I carried long guns–especially on hot calls–making my duty sidearm my backup. More often than not, after I became a plain-clothes special agent, I also carried a J-frame Smith and Wesson revolver, or a Glock 26, as a backup.

What did all of the handguns I carried on duty after 1994 have in common?

NONE of them had an external manual safety of any kind.

I loved my M1911A1; still do. In the early ’90s, I took it to Gunsite for API 250 and won the “man on man” shoot-off with it. It was thinner, felt better in my hand, and was easier to hide under a concealment garment off duty than a Beretta 96D.

But I had to stop carrying it.

Why?

Because after extensive practice with a pistol lacking an external manual safety, I noticed a disturbing trend: I would sometimes forget to thumb down the safety of my M1911A1.

My Recency of Training on “slick slide” systems lacking an external manual safety had, through enough repetitions over time, become my Primacy of Training, supplanting the Primacy I had achieved with the M1911A1 from ’85 to ’95.

This lent credence to advice firearms guru Max M had given me:

“Treat your go-to pistol like a jealous lover, forsaking all others–especially till you have mastered it.”

It was a corollary to another observation Max had made:

“Beware the adversary with only one gun; they might know how to use it.”

Example 3: Different Holsters

John Bianchi, a former LEO and founder of the very successful, eponymous holster manufacturing concern, posited a one gun, one holster dictum he called “Bianchi’s Law:” find a pistol & holster that works for you, and then stick with it.

“It has been my observation that the average person needs to try about three different rigs and guns before the right combination is discovered.”

–John Bianchi, Blue Steel and Gunleather, p. 64

Or, as Omar C, a fellow armorer in my Army ‘Guard artillery battery, told me one drill weekend, regarding a young lady he danced with at a nightclub,

“As the evening wore on, I became disenchanted with her.”

Most serious gun owners have a box full of holsters they tried but found somehow lacking along the way. It stands to reason (duh, you’ll think when you read this) that any time you change holsters, you will need considerable practice to become accustomed to a new draw angle, or any changes in retention devices.

Even a LACK of retention devices, where one was there before, can throw you off under pressure, delaying your draw, thanks to Primacy of Training.

Either way, you will likely continue to bobble the draw under pressure, until you’ve practiced the presentation enough with the new holster for your Recency to become your Primacy. Right after you’ve practiced with the new holster you’ll be fine, but if you don’t practice for a while, watch out.

Whenever you strap on a gun and holster, it’s a good I idea to (slowly, smoothly, carefully) practice a few presentations–in a safe direction with your finger off the trigger–especially (but not only) if its a newer holster, gun, or combo. That way, if anything bad happens after you step out the door, you’ll have front-loaded some Recency with the rig you’re actually wearing, to overcome any Primacy you had with a previous gun / holster combo.

Example 4: Different Grip Angles

As a firearms instructor, every time my agency switched handguns or rifles, I had to oversee “transition” training to the new system.

We seemed to get a new duty gun every 5 years or so. They were always sold to the G as being good for 10 years and 10,000 rounds. Baby agents would shoot theirs several thousand times at the academy, and then we shot them every quarter, often more. Even if they didn’t wear out or break (the Beretta, for example, was not designed to be shot frequently), new people with different tastes in guns would be promoted to the top slots in the firearms procurement biz every few years.

When surveyed over their morning coffee, or around the water fountain, personnel in armed organizations have two favorite guns: the one they used to be issued before the current model, and the one they’re going to get next, as soon as the budget is approved. Nobody ever seems to like the duty gun they are issued at the time.

Firing any handgun is, to a certain extent, practice for every handgun. Mostly we just had to get used to a different type of trigger, or differing weight and length of trigger pull. Sometimes the slide catch would move around between guns (the SIG, especially, was farther aft than on most of the other pistols).

Each new pistol had peculiarities. The H&K USP-C, for example, could get jammed up by lefties pushing in on the pivot pin (H&K called it the slide release “axle,” around which the slide catch rotated), from the right side, with the right thumb, while firing. (The USP-C was not unique in this; you could do the same thing, say, with a Star BM.) We developed ways for lefties to hold the gun that avoided that, and how to fix it if it happened.

Usually there was little problem in shooting passing scores on the qualification courses with the latest and greatest pistol (though some of the fatter pistols, or those with heavier trigger pulls, could be problematic for officers with smaller hands).

Where we would see Primacy of Training rear its ugly head was on “stress courses,” during rapid, close range fire.

For a long time after we transitioned to a new handgun, the rapid fire CQB groups would move up or down a few inches, very consistently between agents. If Wendy hit 4″ high, so would Rob and Lakeisha. When we went to a different pistol again, they might all print a few inches low instead.

This only happened when they were blasting away fast, close enough to hit the target without looking through the sights.

Why was easy to determine; indeed, to predict. Laying one pistol over the other, it was clearly visible that each had a different grip angle. If you laid the grips as closely as possible across one another, the slide of one pistol would point a little up or a little down compared to the other one.

When hard-pressed for time at close range, the agents would rely on the “muscle memory” (Primacy of Training) they had developed with their hands around the previous pistol–rather than the sights–holding their palms at the same angle as required for the old pistol (if they had practiced with that one long enough).

The cure? A lot of SIGHTED dry practice with the new pistol (that “jealous lover” thing again), till your Recency with the new pistol overcomes your Primacy with the last.

3 Case Studies

If you’re still reading this, you have a much higher than average attention span. To reward you, here are are a few more examples of skirmishes in the war between Primacy and Recency.

Case Study 1: Patient Movement

Throughout October 2021, ICSAVE (Integrated Community Solutions to Active Violence Events, a non-profit I volunteer for) taught Public Safety Integration (PSI) to cops and firefighters in Rio Rico, Arizona.

As the world saw on 9/11/2001, firefighters will run into a burning, 110 story skyscraper that is about to collapse, even after the one next to it has, over and over again until it does, to save lives.

But bullets are way too scary–at least for their bosses.

At Columbine, and again at the Pulse Nightclub, victims inside bled to death while EMS waited, hamstrung by local policy, for police to clear the entire complex, to make absolutely sure there weren’t any other ballistic threats.

Immediately after Columbine, police changed their tactics with active killer events. Now, police Contact Teams (also called “hunter – killer” teams) will take tremendous risks “pressing the threat,” moving rapidly to the sound of gunfire / screams, into the Hot Zone (also called the Direct Threat Zone). Their one goal is to stop the killing (Uvalde was an exception, not the rule).

Along the way, those police Contact Teams pass Warm (Indirect Threat) Zones, where the killer(s) have left wounded victims.

PSI teaches LE and EMS to form Rescue Taskforces (RTFs), combined teams of cops and medically trained first responders, to move into the Warm Zones to stop the dying. The police protect the EMS personnel while EMS begins to triage and treat the wounded.

The afternoon of the first day was mostly skills stations. Among other things, we taught them various patient movement techniques, like this one I stole from the Secret Service folks.

And this one, which enables you to walk forward, and even frees up a hand on the rescuer nearest the victim’s feet.

And even this one, we called the “King Tut,” which is good for rough terrain / long distances (many hands make light work), but not so good going through doorways.

Day two of the PSI class was almost all scenario based exercises. The owners of the Esplendor Resort in Rio Rico were gracious enough to allow us to use their sprawling facility, which is currently under renovation, to simulate a school attacked by active killers. Numerous students (many JROTC) volunteered to be moulaged victims in need of saving.

In the afternoon, our RTF exercises had an Active Killer role player providing the “stress inoculating” stimulus of rifle fire: full-power 7.62x39mm blanks from an AK with a Hollywood type adapter (which provides more flash and noise than a box ‘n’ plug adapter).

When they were under pressure to rescue a bunch of screaming kids, with very real sounds of gunfire nearby, the RTFs sometimes used the patient movement methods we’d taught them a few days before (recently).

But more often than not, when it was time to move victims into the next room, or down the hall, to a casualty collection point, they resorted to the primary methods they had practiced in the fire service, like this one, which is very similar to how they schlep people onto gurneys.

Or the the aptly-named Firefighter carry.

Or the classic Rhett Butler – Scarlett O’Hara carry.

None of these methods is any better or worse than any other. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses. It was just interesting, to me, that Primacy once again won out over Recency, when there was some pressure to perform.

Case Study 2: Handcuffing

As a DT, or Defensive Tactics (Empty Hands, OC, Baton, and Handcuffing) instructor for my agency, I used to witness the effects of Primacy in the field when we arrested bad guys.

Like all law enforcement methods, handcuffing techniques evolve over time. To my agency’s credit, they did not just change to cave to political correctness. Sometimes, they changed because of officer safety issues, as the bad guys developed and taught ways to defeat our older methods in their criminal research colleges that we call penal institutions.

Out National Firearms and Tactical Training Unit (NFTTU) actually hired a champion cage fighter to Alpha Test various cuffing methods. They settled on the only one he couldn’t escape from during the handcuffing process.

They sent me to our NFTTU at Ft Benning, Georgia, to learn the new method (and other DT stuff; later I went back to train trainers). We brought that method back to the field. We taught it during quarterly training, and again during annual training events like CWST (Criminal Warrant Service Techniques). Most of our special agents had practiced several “reps,” or repetitions, of the latest technique before their next opportunity to put the “habeas grabbus” on a real bad guy.

Federal special agents, also called 1811 series criminal investigators, tend to be a “seasoned” lot. As with their detective counterparts in state and local police departments, most SAs get that job after years working the street (though some are hired right out of college). Many of us, like me, had started out as patrol officers in state / local departments, and / or in the Border Patrol or as Customs officers at the ports of entry. All of us had learned different handcuffing methods at our respective academies, and most of us had seen several “latest, greatest” techniques come and go over the course of our careers.

Federal special agents, also called 1811 series criminal investigators, tend to be a “seasoned” lot. As with their detective counterparts in state and local police departments, most SAs get that job after years working the street (though some are hired right out of college). Many of us, like me, had started out as patrol officers in state / local departments, and / or in the Border Patrol or as Customs officers at the ports of entry. All of us had learned different handcuffing methods at our respective academies, and most of us had seen several “latest, greatest” techniques come and go over the course of our careers.

Few of the bad guys we arrested offered much if any resistance. Unlike local cops, who often catch bad guys in flagrante delicto, we’d had months and sometimes years to build a case against our subjects. Most of them knew it was only a matter of time before we came knocking. When we did, we rolled pretty heavy (not only for the take down, but for the very involved search warrant after the arrest warrant was served).

One actually told us after his arrest that when he saw us through the window as we piled out of the van, he sat on the bed, and woke his wife. He told her not to be startled when we rammed the door, and not to do anything sudden.

You could almost give the handcuffs to that sort of suspect and ask them to cuff themselves.

But occasionally, we got the other kind.

I found, in the field, that when the bad guys cooperated, our SAs had no problem using the new “resistance resistant” method. But if there was any sort of distraction, if the bad guy fought or had to be chased down, when our agents were running on “autopilot” because the situation was so chaotic, just processing all the stimuli took up most of their mental bandwidth, they inevitably resorted to cuffing the way they’d learned at the academy, or the way they’d handcuffed the most people.

That’s Primacy of Training.

With handcuffing, specifically, the first method we learn tends to be reinforced through many repetitions. First, at the Academy, you do it over and over till you get it right. Then you do it over again, till you can’t get it wrong. Then you practice that method more in the field on real suspects. Patrol officers need to handcuff people more often than detectives conducting long-term investigations of “bigger fish.”

When it’s time for the “roundup” at the end of an investigation taking down a big organization, the lead agent or detective is usually too busy coordinating with the Assistant US Attorney (or District Attorney) assigned to the case, or perhaps interviewing suspects, to actually cuff and stuff any of the players. Usually, a lot of muscle, in the form of patrol officers or perhaps a SWAT / warrant service team, is brought in to do that kind of grunt work. For big federal round ups, we brought in agents from around the country.

So on those rare occasions when a special agent does end up having to arrest someone, it’s no surprise they might not do it the new way they practiced a few times four months ago, and instead revert the way the did it as a patrol officer 2796 times over the course of several years, albeit in the more distant past.

Primacy.

Case Study 3 (back to where we started): M203 Grenade Launcher

So what bit Jethro in the butt? How come he dumped a live HEDP grenade at his team’s feet?

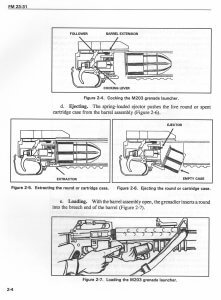

The M203 is somewhat unique. With other weapons systems, the case (empty or still “live”) is pulled out of the chamber by an extractor attached to the breech face (the part that presses up against the back of the case, shutting the chamber like a back door closing). The breech face, in turn, is part of a bolt or slide that moves rearward, pulling the case out of the chamber with it.

With the M203 grenade launcher, the extractor is on the bottom of the breech face. The action (trigger, firing pin, etc) of the M203 sits up against the front of the magazine well on the rifle it’s attached to. It cannot move rearward.

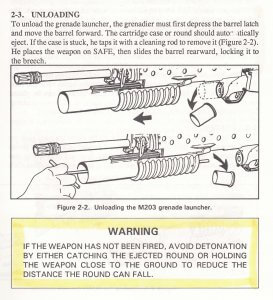

So instead, with a ‘203, the grenadier presses a latch and moves the barrel forward, off the cartridge or empty case.

If you have just fired a grenade, you do not catch the empty case as you move the barrel forward off of (or out from around) it. An empty cartridge case is, after all, nobody’s friend in a fight, so collecting it would be a bad habit to be in.

Contrary to what I’d always been told, there’s no evidence that any of the California Highway Patrol officers massacred at Newhall on 05 Apr 1970 actually collected up brass and put it in his pocket, although Officer Pence was in the process of reloading when he was executed.

No doubt ‘Thro was shown how to unload a live 40mm grenade during the lecture portion of his M203 qualification. It’s on the second page of Chapter 2, “Operation and Function,” in the M203 Field Manual (FM 23-31).

But had Chris ever really practiced that?

Probably not at all. USAF policy was, for very good reasons, “no live ammo in the classroom.” Dummy 40mm cartridges no doubt exist, but I don’t remember seeing any in the 8 years I worked as a Combat Arms (AF small arms) instructor. Jethro’s training did not allow him to achieve what Col. “Slim” Pickens called “safety through competence.”

A truism of adult education states:

I hear, and I forget.

I see, and I remember.

I do, and I understand.

If Jethro had unloaded a live grenade (even a blue-domed practice round), once or even twice, how often was that against the number of times he’d shot a grenade on the range, flung forward the barrel, and dumped the empty casing on the ground, before stuffing in a new one and driving on?

Even if Jethro had (properly) unloaded in the classroom before he went to the range, his range reps became his Primacy of Training.

But wait, you think, how often did he do it? Surely that wasn’t enough reps of either to develop a habit?

I would posit it wasn’t enough repetitions to make either skill reflexive (see below). But if it’s one or two reps versus 30 or 40, the 30 – 40 reps (in Jethro’s case, of opening the ‘203 and letting the empty cartridge case fall to the ground) will probably become the Primacy of Training.

Regardless, it’s just common sense to be careful around live grenades, you think.

Well, true dat.

Chris, God bless him, had many fine attributes.

He was courageous.

He was the only guy we trusted to drive when we went down to Riyadh (indeed, although we got to see the “rocket’s red glare,” I think the closest I came to getting killed over there was in a Riyadh traffic circle).

I love that man, as only a fire team leader can love each member of the crew that helped him or her through The Suck.

But common sense wasn’t Chris’ strong suit. That’s why, by his own admission, his mother nicknamed him Jethro. The brain isn’t fully developed till age 25 or so, and I believe he was south of that.

That kid forgot his own gas mask on–of all nights–the night the war started.

Fortunately, 40mm grenades must be spin armed. The rifling in the 40mm barrel very suddenly imparts a stabilizing rotation to the grenade. When it does, an arming mechanism begins to wind. When the projectile has spun enough times, the fuse will be ready to detonate on impact. Theoretically, the fuse should go “hot” sometime between 14 and 38 meters from the muzzle.

In extremis, if a bad guy jumps into a trench 5 meters from you just as your rifle runs out of ammo, I suppose you could thump him in the solar plexus with a 40mm and hope it doesn’t have time to spin arm. It would be like getting hit with a baseball from a major league pitcher, and would probably take at least a little wind out of his sails. You might have to follow through with some rapid muzzle strikes or butt-strokes. But you would need to call EOD after the fight to clean up the UXO (unexploded ordnance).

The arming mechanism is intended to keep the grenadier from blowing everyone up with a negligent discharge into, say, the inside of a bunker or vehicle.

Or when dropping the cartridge on the ground, as ‘Thro had done. There was a very awkward silence after that sickening thud.

Part II:

Solutions

The only thing harder than learning a knew skill is unlearning an old one

How do we keep Primacy of Training from being a bad thing?

First, we can train right, right from the start.

- Research methods that actually work in the field under stress

- Learn those methods first, and then practice them the most

- Take the time and trouble to do it right, rather than good enough

- Avoid “square, flat range” training scars that are counter-survival in the real world

According to the International Association of Law Enforcement Firearms Instructors,

it takes between 2000 – 4000 repetitions of a psychomotor skill to make it reflexive.

“Reflexive” means done automatically, immediately, without any thought, in response to a stimulus like getting shot at.

The more complex the skillset is, the more repetitions it takes. The more you have practiced it, the more “reps” it will take to overcome a bad or outdated habit and program a new one.

But, who has time to do anything 4000 times?

As with getting in 10,000 steps a day, it’s not as hard as it sounds.

20 GOOD dry presses a night gives you a hundred every week, even if you take the entire weekend off.

52 weeks a year means you can take two week-long holidays and still get in 5000 reps a year, just doing 20 a night during the week.

“A man’s got to know his limitations.”

–Clint Eastwood, a “Dirty Harry,” in Magnum Force

Another thing you can do to compensate for a Primacy / Recency imbalance is to understand and accept it.

Here’s an example of when I decided to just go with it.

Max is one of my oldest and best friends. When his dad died, I flew down to be with him.

When I asked if there was anything I could do, Max requested that I not to go to the funeral. Instead, he asked if I would mind watching his house. At the time, a popular burglar TTP (tactic / technique / procedure) was to read the obituaries and hit the house of the deceased during the funeral, when likely, nobody would be home. Devious–smart, even–but there’s got to be a special place in Hell for people who would do that.

Many gun owners have a safe; Max and his dad needed a vault. Although his collection was physically protected, Max felt an obligation to society to keep his serious hardware out of the wrong hands. Hence, my armed guard assignment.

Max took me into the gun room to select any gear I might need. I had not flown down with a rifle, but one should usually have a long gun for serious social work.

“Never bring a pistol to a gunfight.”

–Steve Wheeler, Officer Survival Instructor

I felt like a kid in a candy store. Seemed like there was at least one of everything in there, even an IMI Galil, one of my all-time favorites.

“I’ll take that M16A2 over there,” I told him, though I was still fondling the Galil. His M16A2 was the closest thing Max had to the rifles I’d carried and trained on.

“I’ll take that M16A2 over there,” I told him, though I was still fondling the Galil. His M16A2 was the closest thing Max had to the rifles I’d carried and trained on.

“I thought you preferred the Galil,” he replied, noticing the admiring way I caressed the Israeli rifle, as I casually practiced a few snaps to the shoulder with it.

“I do,” I said. “But if anything happens, I’ll be shooting an M16, whether that’s what’s in my hand or not.”

The ancient Hebrew King David understood Primacy of Training, even when he was still a grunt.

After he volunteered for a dangerous but strategically vital mission, his King, Saul, tried to outfit David with the best gear available.

Then Saul dressed David in his own tunic. He put a coat of armor on him and a bronze helmet on his head. David fastened on [Saul’s] sword over the tunic and tried walking around, because he was not used to them.

“I cannot go in these,” he said to Saul, “because I am not used to them.” So he took them off. Then he took his staff in his hand, chose five smooth stones from the stream, put them in the pouch of his shepherd’s bag and, with his sling in hand, approached the Philistine.

–1 Samuel 17: 38 – 40

While I and others of my faith believe the rock David used to dispatch Goliath was perhaps the first recorded use of a precision guided munition, there’s no doubt that his full time job (shepherd) afforded young David plenty of time (and, as far as lunch was concerned, incentive) to practice with his sling. As Chris Taylor points out, “That was not the first smooth stone that David had ever slung.”

During the transition period to a new pistol, be circumspect about which of the two–old, or new?–you choose to carry today. Right after a serious practice session with your latest projectile-launching companion, it’s probably a good idea to carry that one, because of your Recency of Training. But if it’s been two weeks since you’ve worked out with your new one (shame on you), you should still carry your old pistol, because of your Primacy with it.

Incidentally, Max’s dad lived well off the beaten path, on the outskirts of town. During the funeral, a car full of obvious gang-bangers pulled into the driveway. When they saw me in the kitchen window, they drove off.

In Sum

Heloderm starts new shooters with bent elbow retention fire–because you are much more likely to need that than full arm extension. By the time most people take “advanced” close range training, the potentially fatal full arm extension habit is already cemented into their subconsciousness by Primacy of Training.

We also try to get students moving as early as possible.

Those are only a few examples of how we strive to make your Primacy of Training right, right from the git-go.

Do your level best not to practice doing things wrong, at least till after doing them right has become habitual.

–George H, lead instructor, Heloderm LLC

*Appendix: About Those Tracers . . .

Stateside, we only carried M193 55 grain “ball” (spitzer boat tail) 5.56x45mm in our M16s. When we deployed to Saudi, they issued us tracer, and instructed us to load our M16 magazines (which, unlike Stateside, we did not turn in to the armory at the end of the shift) with a 1 to 5 ratio of tracer to ball.

That was in the century before zero-parallax reflex optics (“red dot sights”) were available to the common grunt. Our iron sights were not glowing tritium. Theoretically, a tracer now and then helps you hit at night.

It also helps the bad guys zero in on you.

That wasn’t my objection to having them in all of my mags, though. At first, we worked half day shifts, from 12 to 12 (later, our flight worked sunset to sun up). When it was hot outside, we hung out in the shade of KC-135s, 707 passenger jets converted to airborne gas stations. The bottom 1/3 of every fuselage was full of jet fuel.

If we got into a firefight on the flight line, using AGE (aircraft generating ground equipment), Hummers, or KC-135 tires for cover, I didn’t think it would be prudent to go blasting away under all that kerosene with tracers.

Saddam had used the Tu-22 Blinder against Mehrabad International Airport in Tehran during his previous (Iran – Iraq) war. King Khalid International Airport, north of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, was 500 – 600 miles from bases in Iraq, well within the Tu-22’s 3000 mile operating range. There was a wall of F-15s (and other fighters) on constant air patrol over northern Saudi Arabia.

If the Iraqi pilots got through those, the Patriot surface to air missile battery we eventually had at KKIA would probably have made short work of them. I saw what Patriot SAMs did to incoming SCUDs, which are much faster and harder to hit. The Tu-22 could fly supersonic, but the SCUD comes in at Mach 4.

But if any of Saddam’s bombers got through those screens, I could see no better use (indeed, hardy any justifiable use at all) for those tracers, than to throw up a hose of 5.56mm for an Iraqi jet to fly through. Shooting tracers one after another on full auto is a great way to wear out your barrel, but if it helped to take down a low-flying enemy bomber, I figured it would be worth it.

Fortunately, I never had to find out.

Selected Sources

John Bianchi, Blue Steel & Gunleather (Beinfeld, 1978).

James A. Bill, “Morale vs. Technology: The Power of Iran in the Persian Gulf War,” chapter 15 (pp. 198 – 209) of The Iran – Iraq War: The Politics of Aggression. Farhang Rajaee, editor (University Press of Florida, 1993), esp p. 199.

W. Seth Carus, Ballistic Missiles in Modern Conflict (Center for Strategic and International Studies, 1991). A revised and expanded version of his previous work, Ballistic Missiles in the Third World.

Richard Hallion, Storm Over Iraq: Air Power and the Gulf War (Smithsonian, 1992). p. 156.

Chaim Herzog, The Arab-Israeli Wars: War and Peace in the Middle East, from the War of Independence through Lebanon (Random House, 1982), esp. p. 161.

Michael Peck, “How Israel’s Air Force Won the Six-Day War in Six Hours,” The National Interest (02 Jun 2017).

Mike Wood, Newhall Shooting: A Tactical Analysis (Caribou Media Group, 2013) esp. pp. 56 – 58. The most thorough, and most thoroughly researched, work I have read on the 05 Apr 1970 gunbattle. Incidentally, if you’ve ever been to the Magic Mountain amusement park, you’ve driven right past where that shooting took place.