MSgt Marion L. “Butch” Rupert Jr.

29 Apr 1950 – 24 Dec 2018

His parents named him after his dad. I don’t know why he preferred to be called Butch. He was a Master Sergeant (MSgt). He drove an old yellow and white Chevy pickup.

Butch was the Superintendent of the Francis E. Warren AFB Combat Arms, Training, and Maintenance (CATM) section.

When the Army uses the phrase Combat Arms, they are referring to the big three at the pointy end of the spear: Infantry, Cavalry / Armor, and Artillery. When the Air Force uses the term, it means small arms, or as they say, “ground weapons.” CATM were the “red hats” who ran the firing ranges.

MSgt Rupert was also the shooting coach of our Olympic Arena (Missile Combat Competition) Security Police team. OA was a Strategic Air Command competition between the various nuclear missile wings.

Butch was very even-keeled. He was the opposite of flamboyant. Nothing seemed to flap him.

He knew his business.

Not even A1s

In the 1980s, the USAF was still issuing original M16s (not M16A1s or A2s), with iron sights. They had very few of the modifications, such as enhancements to the extractor spring, considered essential for reliability today. Those upgrades occurred in fits and starts over the years, as shortcomings in the original AR15 design, and fixes for them, were discovered. Our rifles didn’t even have forward assists–although some of ours had been repaired with replacement upper receivers that had the raised bump where a forward assist would be; apparently they had been milled after the forward assist became standard on the M16A1.

I was a rifleman by trade. Security specialists were the infantry of the Air Force. I thought I knew a lot about M16s.

In my own defense, I knew a lot more about them than most of my peers, because I was what one ATFE friend calls a “stroke.” A stroke is a person who really gets into guns. Besides, I had read a lot of military history, including the works of SLA Marshall, who was less than charitable toward the M16.

“Fifteen yards beyond where Keller lay,” Marshall wrote in West to Cambodia, “his own [M16] rifle jammed. (Hunter, a graduate mechanical engineer from Georgia Tech, despised this weapon.)” Indeed, that entire book, published in 1968, was full of examples of M16s having stoppages in the middle of fire fights.

And it was only one of many sources I’d read disparaging the AR series, at least before they worked the bugs out. One periodical I read in 1982 quoted an un-named Czech arms manufacturer as having written “It is a sad fact that nation with such great firearms tradition has selected such poor weapons [M16A1s] for its armed forces. . . Motherland of great J. M. Browning deserves a better rifle, I think.”

See Bayonets in the EFK category of this website for more information about the M16’s growing pains.

Sometimes, old guys know stuff

As our command-wide competition neared, Butch told us we would not be cleaning our rifles in the week before the match. “They actually shoot a little tighter when they’re dirty,” he said. He meant dirty from carbon, not mud or dirt.

My hand immediately shot into the air. I was obsessive with firearms maintenance. I literally wore out guns by cleaning them more than necessary.

“I’m not worried about dropping a point because my rifle isn’t accurate enough,” I objected. “I am worried about dropping 5 points when a pop-up goes down while I’m trying to clear a jam.”

“They’ve done tests,” Butch replied, “and as long as it’s well lubed, these things will fire thousands of rounds.”

“Maybe,” I started, “but if you talk to somebody who was in Vietnam–“

“I was . . . in Vietnam,” Butch replied, slowly and succinctly.

“Yeah. Well, if you talk to somebody who was in the Army in Vietnam–“

“I was . . . in the Army . . . in Vietnam,” he said, even more slowly.

I decided to shut up and color.

That was the only time he ever mentioned his Southeast Asian service, in my presence. I later found references to it in his obituaries.

It was not unusual for people who’d done an enlistment or two in the Army or Marines to cross over to the Air Force once they started having families.

It’s never been a secret that USAF enlisted personnel have nicer accommodations than officers in other services.

When former soldiers and Marines enlisted in the “Airedales,” many were assigned to the Security Police (now called Security Forces) or CATM (then a separate career field from the SPs), two of the closer USAF analogs to their previous skill sets.

Butch was one of those.

MSgt Rupert taught me a lot about the rifle, about marksmanship, and about staying calm under pressure.

He was also the first instructor I remember who used the heuristic technique of placing a finger over the student’s trigger finger, so they could learn by feel the way he wanted them to pull the trigger. I’m sure he didn’t invent that, but I learned it from him.

He showed us methods to slap the trigger (like a skeet shooter with a shotgun) without ganking the sights off, during rapid-fire courses.

I’d been handling AR series rifles for 6 or 7 years before I met him, but Butch was the first to teach me a quick, effective way to clear (the less than common) brass-over-bolt stoppages: lock the bolt to the rear, hold it to the rear with firm thumb pressure on the bottom of the ping pong paddle, and shove the charging handle forward.

MSgt Rupert studied, among other things, the techniques the Russian shooting teams used in the Olympic games. Unlike the Russkis, we weren’t into doping–they took drugs to steady their heart rate–but they also knew some other things about handling match pressure.

Butch on Slingology

All our M16s had the old “pencil” barrels. This made them very light, but the pencil barrels could literally be bent by using them to pry the shipping bands off of C-ration crates.

One of the changes when they came out with the M16A2 (that has stayed with us in the M4s) was to beef up the front of the barrel.

One method used by competition shooters is slinging-in: using the sling around your biceps to form a triangle (that most stable of shapes in construction) between the sling, your upper arm, and your forearm supporting the rifle.

Slowfire competitors sling-in so tightly it hurts, and even wear shooting jackets with sling attachment points. Our biathlon-type shooting match was supposed to represent combat, so a match shooting jacket would’ve been considered “gaming it.” On the other hand, a hasty sling (using the sling as it comes on the rifle, as opposed to a more deliberate loop sling, which often requires taking the sling off its rearward attachment point) is a tool available to any infantryman at a moment’s notice.

MSgt Rupert let us try that–teaching us that slinging in (with even a hasty) too tightly on a pencil barreled M16 would actually change its point of impact considerably.

Shooting jackets also have built-in shoulder and elbow pads. We had flak jackets instead. Those could be problematic, as the flak jackets had collars to protect the wearer’s neck from explosive fragments. They worked fine when you were vertical. The collar of the flak jacket pushed up on the back of the PASGT (“Fritz”) helmet that was adopted in the 1980s, knocking the front of it down over your nose when you were in prone.

Butch showed us that if we tucked the collar of the flak jacket under the shoulder pieces, it would fix that problem.

Mastering the Iron Sights

Butch was an expert in the now-dying art of using “iron” rifle sights.

The front sights of the M16 and the M16A1 had round cross-sections. They were circular when viewed from the top. One of the changes when they came out with the A2 was to go to a squared off front sight, which was crisper and easier to focus on (that change has stayed with us). The M16 sights were also gun metal grey, and sometimes, when worn, were lighter. My eyes were much clearer then, and I could focus on the front sight, but Butch showed us how to make it easier to see.

He used to take a piece of masking tape, fold it in on itself lengthwise, and set it on fire. Then, holding the flaming tape under our front sights, he would blacken them with carbon from the smoke. That black front sight stood in sharper contrast to the green targets we shot at.

Butch had a sense of humor, too. Once, when I wasn’t looking, he also blackened the (already black) stock where I put my cheek. It took me a while to figure out why the others were smirking at me–I had a black smudge on my face, like a chimney sweep from Mary Poppins.

MSgt Rupert taught me where to hold that front sight post when canting the rifle to see through the rear peep, while wearing an M17 gas mask.

That doesn’t matter much when you are shooting scaled silhouettes at 25 meters, because that’s the initial intersection where we zeroed military rifles. But in those days we shot at actual distance. It matters when your target is really at 200 or 300 meters. Instead of going up through your line of sight, over it, and dropping back down through it (assuming no wind), the trajectory of a bullet from a canted rifle goes up through the line of sight, crossing through it at about the initial intersection (just like with a vertical rifle), but then arcs up and over toward the side the rifle is leaning to, from the shooter’s perspective.

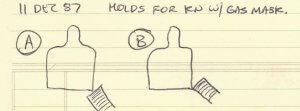

Here’s a sketch from one of my shooting logs. We were training on a 50 to 350 meter pop-up range at Ft Carson. The outlines represent standard, olive drab, E-series human silhouette targets (we called them “green Earnies”); the dark rectangles represent the front sight of “Paullus,” my issued M16. I hit more often with the hold labelled B.

The pop-up mechanisms for targets on Army ranges flipped the target down when they sensed a hit. A near miss over the shoulder, next to the head, of an Earnie would not be registered as a hit, but a low miss skipping the bullet (and rocks / dirt) into the target might; so we held a little low when shooting on Army ranges. Decades later, when I was shooting steel targets at Thunder Ranch, Clint Smith told us that in a real gun battle, it’s better to hit low and skip bullets into them than it is to miss high.

I named my M16, sn 306130, after the Roman consul who tried to dissuade Varro from giving battle to Hannibal at Cannae. Paullus was my on-duty companion from 1987 through 1992, including my deployment to Op Desert Storm.

During the 1998 Texas Police Games, I canted my issued M14 slightly, to get a more stable position. But I forgot to adjust my front sight hold as Butch had taught me a decade before, and it cost me at 200 meters.

Butch and the M203

Butch also taught me that grenade launchers are fired like recurve bows–intuitively.

By feel.

Like throwing a baseball from left field to third base.

M203 Sighting Options and Effective Range

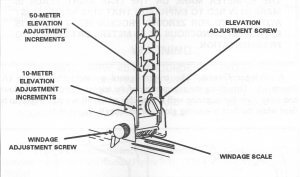

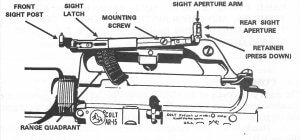

In those days, the M203 40mm grenade launcher had two main sighting systems:

- A more precise, peep and post quadrant sight, and

- A leaf, or “combat,” sight.

The leaf sight had triangular wings coming in from the sides, like rungs of a ladder, in 50 meter increments from 50 to 250 meters.

After estimating the distance to the target, you lined that distance on the leaf sight up with the rifle’s front sight.

The quadrant sight was adjustable out to 400 meters, the maximum range of the system, although the “effective” range of the ‘203, against an area target, was 350 meters. It bolted onto what we called the “Samsonite” (carrying handle) of the M16.

Maximum range is the distance the projectile will travel under ideal conditions. Maximum effective range is the distance you are as likely as not to hit a target.

Specifically, effective range was the distance the so-called “average” soldier could hit the target 50% of the time. For most weapons, that target was a standing green Earnie. When calculating effective range, two types of targets are considered:

- Point, and

- Area.

With a grenade launcher, a point target might be a vehicle, or the window of a building or bunker. The main purpose of a grenade, after all, is to take out people who are bunkered down out of your direct line of sight (we call that being “in defilade“). If the bad guy doesn’t expose enough of himself through the 3rd floor window of a concrete building for you to shoot him with a rifle bullet, you can lob a grenade in through the window and nail him from behind. Against a point target, the M-203 had a maximum effective range of 150 meters.

An area target might be an enemy camp, or a platoon spread out on patrol. You don’t expect to hit any particular enemy combatant, but you hope to at least injure a few of them. A civilian equivalent of an area target was the Route 91 Harvest music festival in Las Vegas, Nevada. The maniac on the 32nd floor of the Mandalay Bay wasn’t trying to hit any specific person on 01 Oct 2017; he was just spraying bullets into the literally captive audience.

Apart from being Satan’s spawn, that murderer in the Mandalay Bay was a lame bastard. Where’s the challenge in hitting anywhere in dozens of acres of real estate?

“I prefer to fight the European armies, but they do not fight as men – they fight as dogs! Men prefer to fight with swords, so they can see each other’s eyes! Sometimes, this is not possible. Then, they fight with rifles. The Europeans have guns that fire many times promiscuously and rend the earth. There is no honor in this – nothing is decided from this . . ..”

–Sean Connery, as the Berber chieftain Raisuli, in The Wind and the Lion

The M433 HEDP (High Explosive Pual-Purpose) grenades we were issued could penetrate 2 inches of armored vehicle, but they also produced fragmentation capable of injuring 50% of enemy personnel with 5 meters of detonation. Hence, the blast radius of an M433 40 mm grenade was 5 meters. As with tossing horseshoes, close sometimes counts.

Limitations are Made to be Pushed

The quadrant sight worked really well when you were trying to put a grenade through the firing port of a bunker. Many grenade launcher firing ranges have a 2′ x 2′ squares representing a window, at ranges out to 150 meters.

The quadrant sight was relatively fragile, though. I did not anticipate it still being there 30 seconds into an ambush, after I had rolled away from my second or third 3 – 5 second rush (“I’m up, He sees me, I’m down”). I made it a habit to leave the quadrant sight off the gun, in a protective pouch, and worked harder on being good with the leaf sight instead.

Although vehicles were, strictly speaking, “point” targets when lobbing grenades from a launcher, our grenade range at FE Warren AFB had small, deadlined (kaput) armored personnel carriers (I believe they were M114 APCs), as targets out to about 400 meters.

Just because Field Manual 23-31 said the max effective of an M203 was 350 meters for “average” soldiers, didn’t mean that had to be MY max effective with it.

Butch encouraged us to push beyond what was expected.

When I became a federal law enforcement firearms instructor, I followed Butch’s example. We qualified out to 25 yards with our pistols–but I occasionally had our agents hitting things at 50 – 100, just to show them they could do it if they needed to.

40 mms are like baseballs

Once, when MSgt Rupert was running me through an M203 course, I did OK shooting through the “windows” at closer distances, but couldn’t hit the farthest APC using the leaf sight. At that distance, you had to look at the rifle’s front sight over the top of the leaf sight, guesstimating how much higher another 50 meter increment would be. The bird cage of the flash suppressor might even block part of your view, requiring you to mentally superimpose the image of the target area from your non-dominant eye onto the image you were seeing (or not seeing) through the sights.

To complicate matters further, it was a typically windy Wyoming day, and that big, fat, slow moving (250 feet per second) 40mm grenade got pushed around by the wind like a paper boat.

I just couldn’t connect with that farthest APC.

Butch stood beside me, patiently, through missed shot after missed shot.

Finally, he grabbed me by the arms and moved me around, still standing beside me, not even looking anywhere near a sighting system. He just looked downrange at the APC. After he had me adjusted where he wanted, he held me still and said simply, “Pull the trigger.”

We hit it.

Pushing the limits of the rifle

One staple of military small arms training was to memorize and be able to spout off a bunch of esoteric but mostly useless facts about the rifle. For example, our M16s weighed 6.35 pounds empty, but 7.76 pounds with a fully charged (loaded) standard capacity (30 round) magazine inserted. Who cares? It weighed as much as it weighed. (It was designed to be lightweight, but today’s shorter M4s weigh nearly as much as a WWII M1 Garand with all the crap they hand off of them these days.) It got heavier as the day grew longer.

We had to memorize, as if it were Gospel, that the maximum range, the farthest it would throw a bullet at optimal trajectory, was 2653 meters. But what if there was a headwind, or tailwind? What if the ammo was hot, resulting in higher velocity and (combined with hot air) less wind resistance? That number may have been an average. The less precise “About 1.6 miles” would’ve been easier to visualize than “2653 meters.” But they never told us why it was important that we knew even an approximate max range.

Butch was not into spouting, or hearing us regurgitate, esoteric facts. If he brought up max range at all, it would’ve been something like “If there’s a school within a mile and a half of you, you need to be careful where you point that thing, because the bullet from an accidental discharge could fly that far.” (We called them “accidental” discharges back then; now we use the more accurate term negligent discharge.)

One M16 “spec” that meant more to us was maximum effective range. That was the distance at which the so-called “average” soldier could put half (no more, no less) of their bullets into a green Earnie target, anywhere on the target–even just creasing the edge.

For the M16, max effective was 460 meters.

But Butch wasn’t about training “average” riflemen. He put a white paper picnic plate on a green Earnie at 500 meters. We each shot a single standard capacity (30 round) magazine at it. After we had all shot at it, Butch asked us to guestimate how many hits were on the plate (not just on the green Earnie). The person who guessed the closest got dinner on Butch and MSgt Ferguson, our Olympic Arena coaches.

Butch often had us “call” our shots. What happened right before the trigger broke determined where the bullet went on the target, and an experienced rifleman should be able to tell about where it went before going downrange to look at the target. In this case, based on how we felt about the shot, we tallied our estimates of which were good shots, on the white paper plate, which were merely adequate (anywhere else on the green Earnie), and which we shanked off the target altogether.

Even though the “average” rifleman could only put half the shots from an iron sighted M16 anywhere on a full-sized human silhouette at 460 meters, Butch had us putting a significant portion of our shots on a pie plate at 500.

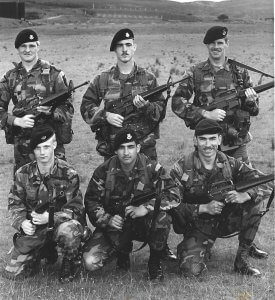

These security policemen from AF bases in England got to shoot at 300 – 500 meters on the range behind them in a teambuilding competition against British RAF Regiment riflemen. The British SA80 bullpup rifle had an optic, the SUSAT (Sight Unit Small Arms, Trilux), but the M16s had iron sights, so the Blokes took off their SUSATs and shot with irons to make it fair. With the exception of competitors and designated marksmen / snipers, few service personnel outside the Marines shot outside of 400 meters in the 1980s, and few do today. Butch gave us such opportunities.

Did you get a good look?

Butch’s affect was completely deadpan.

Our GPMGs were Vietnam era M60s. The ’60 borrowed its feed mechanism from the German MG42 of WWII, and its operating mechanism from the German FG42. It weighed 23 pounds.

The “hog,” as we called it, only fired full auto, but it had a low cyclic rate. Butch could consistently squeeze off single shots, hopping off the trigger before the second shot, but most of us didn’t have The Force flowing through out trigger fingers like Butch did, and could only get it down to 2 or 3 shots per.

Of course, it wasn’t made for that. We were supposed to fire 6 to 9 round bursts, and usually did.

Each hog came with at least one spare barrel. Every few hundred rounds, the AG (assistant gunner) would swap out the M60’s barrel to keep it from overheating and wearing out the rifling.

One day we were firing the hog at the DOE Central Training Academy’s pop-up (Duelatron) target range, on the back side of Kirtland AFB in Albuquerque. Butch, our shooting coach, and MSgt Ferguson, our team coach, were standing by, stoically watching us nailing the pop-up targets.

The pair of crusty older NCOs stood like statues, just like in the photo at the top of this article.

After the first few hundred rounds, we swapped out the ’60 barrel as per SOP. But MSgt Ferguson must’ve been looking away, and we must’ve done it very quickly. The AG (assistant gunner) set the old barrel down, using the thick asbestos mitten that came with the spare barrels, because it was scaldingly hot.

After a few more belts of ammo, MSgt Ferguson was concerned we were going to melt the barrel on the hog. He reached for what he thought was a cold, unused barrel and picked it up–with his bare hand–to hand it to the A-gunner. Of course, it burned him severely.

But MSgt Ferguson wasn’t about to admit to such a massive pooch-screw in front of the troops. A leader must maintain a certain aplomb. He stood back suddenly, wincing only slightly, and endeavored to continue looking at us shooting the pop-up targets as if nothing had happened. Ferguson never made a sound. MSgt Rupert appeared not to have noticed.

After a few minutes, still continuing to “play it off” as if nothing had happened, MSgt Ferguson dared to glance down at his reddened palm.

When he did, Butch said, in his slow, deadpan drawl, “You get a good look at that ’60 barrel?”

“I’ve seen ’em before,” MSgt Ferguson replied.

Ready to Go

I knew my days to learn from MSgt Rupert were limited when I was on the phone at his desk.

Kids, there was a time when phones were in fixed locations. The receiver, a banana shaped thingee with a speaker for your ear and a microphone for your mouth, was attached by a chord to the rest of it, so you had to stay near where it was plugged in.

The upside, if any, was that you never forgot where you put the phone.

Anyway, I needed to make a call, and he wasn’t at his desk, which had a phone, so I parked myself in Butch’s chair. During the call, I needed something to write on, so I fished around for some scrap paper. There was a 3M Post-it notepad (then a newfangled product, which had only been around since about 1980) in a prominent location on MSgt Rupert’s desk. “That’ll do,” I thought, pinching the telephone receiver between my shoulder and my ear, and grabbing a pen.

The top Post-it already had a number written on it. Probably old data, but just in case it meant something to somebody, I peeled it off and stuck it next to the pad, preparing to write down what I needed on the next Post-it.

It also had a number on it already.

As did the next. And the next.

Every single Post-it in the pad had a number on it.

It was easy to establish a pattern. The number on the top Post-it was something like 327. The next one down was one less, 326. And so on.

Butch had less than a year to go until retirement. 327 (or whatever it was) days, in fact. But who’s counting?

Butch was outstanding at his job. He might even have loved it (one must, to be as good as he was at it). But when it was time to go, he was ready.

I started writing this homage to him before I realized he was no longer with us. As I researched him on the internet, I came across his obit.

MSgt Marion L. Rupert was an artist. The finely honed skills of the riflemen on our team were his works of art.

God rest your soul, Butch. Thank you for your wisdom and patience, sir.

–George H, Lead Instructor, Heloderm LLC