Bayonet Origins, Effects, and Exploits

Hunting Origins

From what I’ve read, bayonets (knives or spikes mounted to firearms) were first developed as a backup for hunting in the 1600s, the age of slow-to-recharge and unreliable ignition muzzle-loaders.

If a hunter wounded a wolf, panther, or wild boar, for example, and the animal charged him before the hunter could reload, a long pokey edged weapon mounted to the front of the firearm could possibly keep the hunter alive and in business.

The original bayonets were mounted by stuffing their narrow hilts (handles) IN to the muzzle of the firearm. Theoretically, this could be done a lot faster than ramming another charge all the way down the barrel, followed by a round ball, and then putting more powder in the pan. If the animal closed too quickly, the bayonet could be used in-hand, like a sword or knife, but if on the musket the hunter had a little more reach to stay clear of claws, tusks, horns, and fangs.

Pole Arms & Fear of the Cold Steel

During the middle ages and the renaissance, foot soldiers used a lot of pole arms: spears, pikes, and halberds (like a spear with a hook or axe on it).

A farmer might’ve been too poor to afford a horse or armor, but he found that the pruning hook he used on his lordship’s apple trees was also a useful tool for unhorsing an enemy knight. The halberd and the pike became effective means of evening the odds against cavalry.

When muskets began to dominate the battlefield, the long bayonet was a way to convert a slow-loading, but also long, muzzle-loader into a field expedient pike, and for mostly the same anti-equestrian reasons as the original pole arms.

Troops often stood stoically against (or even marched into) volley after volley of round musket (and later, badminton shaped Minnie) balls. The sound of gunfire–even black powder gunfire–is terrifying, but the projectiles usually could not be seen in flight, even when their effects were blatantly evident.

Almost nobody, though, stood up to a bayonet charge.

I believe our inherent fear of edged weapons comes from the fact that claws and fangs were viable threats when our DNA was being patterned. Unlike, say, instinctive fear of snakes, gunfire has not been around long enough to be part of our genetic memory.

Demoralizing Effects of Bayonets

General George Patton spoke of the psychological effect of glittering steel coming to explore your guts. More than most, Patton understood what Napoleon was talking about when he said that moral (mental) factors are far more important than actual physical conditions in combat.

- “It’s the cold glitter of the attacker’s eye, not the point of the questing bayonet, that breaks the line.

- It’s the fierce determination of the driver to close with the enemy, not the mechanical perfection of [the] tank, that conquers the trench.

- It’s the cataclysmic ecstasy of conflict in the flier, not the perfection of his machine gun, that drops the enemy in flaming ruin.

- Yet, volumes are devoted to armaments; and only pages to inspiration.

It lurks invisible in that vitalizing spark, intangible, yet as evident as the lightning–The Warrior Soul. The fixed determination to acquire The Warrior Soul, and having acquired it to either conquer, or perish with honor, is the Secret Of Victory.”

–George S. Patton, Jr, 1926

Patton’s words above were quoted by Charles M. Province in Patton’s One-Minute Messages, a book I read to my kids at bedtime.

Bayonets in the American Civil War

In his handout for our Thunder Ranch Old Rifle class, Clint Smith noted that even in the American Civil War, when rifle reloading was a time-consuming challenge, only 1% of the KIAs were killed by bayonets. The following elaboration is from page 29 of Jack Coggins’ Arms and Equipment of the Civil War:

“The bristling points and the glitter of the bayonets were fearful to look upon as they were leveled in front of a charging line, but they were rarely reddened with blood.”

–Confederate General John Gordon

“. . . Corporal Selby killed a rebel with a bayonet there, which is a remarkable thing in battle and was spoken of in the official report.”

–Oscar Jackson, in his Colonel’s Diary

Only 6 out of 7302 wounded during Grant’s Wilderness campaign were listed as having been injured with a bayonet or sword. Be wary, however, of survivorship bias when analyzing such statistics.

But lethality is only one measure of a weapons system’s effectiveness. With a psychological weapon like the bayonet, it may not even be the most important criterion.

Milliken’s Bend

There were some–excuse the expression–pointed exceptions to the novelty of bayonet use during the Civil War. For example, there was a minor fracas at a place called Milliken’s Bend on the Louisiana side of the Mississippi. It was only small in relative terms; each side “only” had about 1500 men, far bigger than a rumble between rival gangs. Compared to the attack on the nearby Arkansas Post, where a garrison of 5,000 Confederate defenders was overwhelmed by 30,000 Federal troops, backed by a flotilla of Union gunboats, Milliken’s Bend would seem almost a skirmish, regardless of how big and important it must have seemed to every single participant who was there when it was happening. And compared to the siege of nearby Vicksburg, the fight over the minor Union Supply Depot at Milliken’s Bend, when most of the supplies had already been moved, might seem strategically unimportant.

Ironically, the much larger siege of Vicksburg, which would ultimately be the final nail in the coffin of the Confederacy of the West and would propel Ulysses S. Grant not only to command of the Union Army but to the Oval Office, was the reason the Milliken’s Bend battle happened at all. Texas troops were trying to raid supplies and to cut at least part of the noose that was tightening around Vicksburg, the largest remaining Southern port.

Milliken’s Bend was so unimportant to the Union Army when the Texans attacked on 07 June 1863, it was mostly manned by third string benchwarmers: recently liberated former slaves. They were issued older weapons and had not even had much time to train with them. Their inaccurate fire and inefficient reloading failed to stop the Rebels from reaching their first line of defense, a breastwork on top of a levee.

But then . . .

“The African regiments being inexperienced in the use of arms, some of them having been drilled but a few days, and the guns being very inferior, the enemy succeeded in getting upon our works . . . Here ensued a most terrible hand to hand conflict of several minutes duration, our men using the bayonet freely, and clubbing their guns with fierce obstinacy.”

–US Brigadier General Elias Dennis

Even the Confederate Commander, Brigadier General Henry McCulloch, concurred with Gen Dennis’ assessment, saying the Black men fought with “considerable obstinacy.” The ferocity with which the previously untested Black soldiers fought surprised Whites on both sides who had previously underestimated them, including the Federal 23rd Iowa Infantry, veteran soldiers who fought alongside them.

The Blacks at Milliken’s Bend had several cogent reasons to fight hard.

- For one, they had limited terrain for withdrawal. Their backs were to the Mississippi River. I am a fairly confident swimmer, but that stream is a mile or more across. I wouldn’t want to try it, especially with enemies on the bank shooting at me.

- As former slaves, only recently liberated, they had no reason to love men who had rebelled to preserve the institution of slavery.

- The Confederates had a policy of returning captured slaves to their former masters. Slave owners in Louisiana, as a general rule, were known to be the most egregious when it came to mistreatment of their human chattel. That’s where the term “Sold down the river” comes from.

- The Rebels also had a policy of killing any slaves found committing “insurrection” by bearing arms against their (former) masters. White Northern officers who incited Blacks to insurrection, by arming and leading them in battle, were also subject to execution.

For these, plus at least 1500 individual reasons, the defenders of the Union Depot at Milliken’s Bend fought at close quarters with bayonets and buttstocks like banshees. The 11th Louisiana Infantry (African Descent), in particular, gave up hardly any ground, even when the other Union troops, Black and White, were being pushed back to the second levee.

The carnage of the close range, fixed bayonets fight was extreme, even by Civil War standards. The Union suffered 492 losses (1/3 of their troops) at Milliken’s Bend:

- 119 Killed in Action

- 241 Wounded in Action

- 132 Missing in Action. At least some of the MIAs, Blacks and their White officers, were later learned to have been executed after capture.

The vast majority (427) of the Union casualties were of African descent.

The Rebels lost 185, but the disparity in casualties tells only part of the story.

I once lost a boxing match to a Golden Gloves champ. It was an epic beating, but he won by decision, not KO. He was pummeling me so frequently and severely that in the third round, the ref took me aside. “You sure you want to go on with this?” he asked. I asked only where the enemy could be found, since both of my eyes were nearly swollen shut. I wound up on a soft diet for a couple of weeks.

That Golden Gloves guy ran into me later and said he greatly admired the way I hung in there, even though I was taking a savage thumping.

Likewise, Southerners grew to respect the courage of Black troops under fire, and their savagery in hand-to-hand bayonet combat. More importantly, their performance at Milliken’s Bend so impressed White Northerners than many dropped their objections to Colored troops, which led the way to greater Black recruitment by the Union Army.

Regardless of how many were stuck with bayonets at Milliken’s Bend, the way those former slaves wielded them changed the course, if not the outcome, of the war.

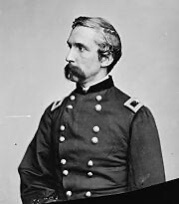

Little Round Top

It’s possible that a single bayonet charge altered the course of the American Civil War.

During the pivotal battle at Gettysburg, the “high water mark of the Confederacy,” if the Rebels had taken Little Round Top, they might have been able to flank and therefore “roll up” the entire Union line. Col. Chamberlain, in command on Little Round Top, understood its importance and determined to defend it at all costs. When the 20th Maine troops ran low on ammo, they charged down the hill with fixed bayonets, routing most of the Rebel forces, and ensuring the Union’s victory. How many Rebels they actually stuck with bayonets is not nearly as relevant as that bayonet charge’s effect on the outcome of the battle, and hence, on the tide of the war.

Effectiveness = results, not kills

The Britts were disappointed with the number of Argentine aircraft they were able to down with their complicated and expensive surface to air missiles in the Falklands. However, the presence of their SAM threat forced the Argie pilots to operate at insanely low altitude. Consequently, many of the Argentine bomb fuses did not have time to arm before hitting their targets. The SAMs-launched-to-aircraft-killed ratio doesn’t tell the whole story of their effect on the outcome.

It’s an age-old military axiom that “Nobody stands up to the cold steel.” Most of the time, when the bayonets came on, the other side tended to bug out.

*****

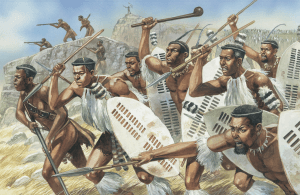

The Anglo-Zulu War of 1879

Like Milliken’s Bend and Little Round Top, the following two engagements in January 1879 illustrate both the usefulness of bayonets when used defensively, and the fearsome effect of cold steel coming to explore your guts.

Isandhlwana

The cold steel which led to this rout was not of bayonets; rather, it was the spear points of Zulus outnumbering the 1200 infantry defenders, plus assorted artillery, horsemen, scouits, and support personnel, about eleven or twelve to one.

The Zulus had some few rifles. Some Zulus were crack shots, but like the native Americans of the same era, they did not have industrial armories for repairs. Ammunition was usually in short supply, so they didn’t waste much practicing, except at living targets (for food or war). The Zulus travelled light and fast. They did not have the huge pack trains that made European armies formidable but slow and cumbersome.

They had some clubs (the British called those “knobkerries”) and throwing spears (asegais), but the preferred tool of the Zulu warrior was the iKlwa, a short, broad bladed stabber. The shaft of that spear was not long enough to balance it for throwing. It needed to be used at smell-his-breath distance, and since it hadn’t been thrown away, it could be used over and over and over.

The British of the 19th Century, like the Americans of the 20th and 21st Centuries, preferred to keep their enemies far away with the “superior firepower” of accurate bullets from rifled bores, along with artillery and rockets (and in the next century, air support). Bayonets mounted on rifles adversely affect accuracy at distance. When thousands of Zulus, in a masse two miles wide, began covering the South African plains to their front and sides, the Red Coats formed in lines, their backs to their camp, the small mountain of Isandhlwana behind it, with their bayonets on their belts, not their rifles.

The (soon to be ovewhelmed) British dismounted cavalry scouts “had no proper bayonets, only a fitting at the end of the short carbines to which a hunting knife could be attached” (Donald R. Morris, The Washing of the Spears, p. 373). What Morris meant was, the short cavalry carbines had short knife bayonets. The Martini Henrys carried by the British infantry had a “proper” 21.5-inch bayonet with a 3-bladed, triangular cross-section.

The British units were formed up with some little distance between them, spread out in a roughly L-shaped line two soldiers deep. Some of the infantry started out with 70 rounds of ammunition per person, but most had 40 to 50, and the Natal Native Contingent scouts at the “knuckle,” the bend of the L which was most exposed to the main mass of the Zulus, only started the battle with five rounds apiece. Each British unit had a quartermaster in the rear standing by with 30 additional rounds for every soldier in their unit–key word, their unit–plus the camp had 480,000 rounds of rifle ammunition in reserve.

Initially, things were going quite well for the Red Coats, but as the battle wore on and the Zulus refused to stop getting closer, ammo began to run low on the line. Quartermasters were at first reluctant to share ammo with anyone who wasn’t in their own unit. Seriously. Why not? Just like today’s Air Force Combat Arms instructors with literally hundreds of thousands of rounds of ammunition in their armory, earmarked specifically for expenditure in training, they had to account for every single round, every single day. Like counting squares of expendable toilet paper. Stupid.

Remember what I said about how “nobody stands up to the cold steel”? On came the broad heads of the iKlwa spears in the strong hands of thousands of angry Zulus shouting their war cries: “uSuthu! uSuthu!”

The British NNC scouts at the corner of the L ran out of ammunition first and fled from the oncoming iKlwas first, leaving a gap in the line 300 yards wide, through which the Zulus poured like a tidal wave. The British units closest to the gap had no time to even mount their bayonets to their rifles before they were taken from the rear. Units farther away fixed bayonets and fought in hand-to-hand combat through the camp to the foot of the mountain, but in the end, only 50-some-odd Europeans escaped the shadow of Isandhlwana alive.

Rorke’s Drift

. . . was a resupply point, a Christian missionary’s church, and hospital about a day’s ride back from Isandhlwana, manned by about 120 troops. The Zulus, weary from battle and from covering so much ground at a run, but determined in their desire to expel the foreign invaders, pursued those fleeing Isandhlwana to Rorke’s Drift. The Zulus had 1200 more rifles than they started with, and for a change, a wealth of ammunition.

In the Biblical account, King Saul offered David the use of his own sword, one of the finest in the land. But David chose to take on Goliath with the sling he had grown up usning, and trained with every day when he was seeking lunch or just bored watching sheep.

The Zulus brought their recenlty acquired, slightly used rifles to Rorke’s Drift, and shot many of them, but as with David, the iKlwa remained the extension of their hand they had trained with practically from birth. To use their iKlwas, they had to get within stabbing distance.

The stabbing worked both ways. Bayonets were used as frequently as iKlwas, even within the close confines of the hospital.

The British fought a strictly defensive battle at Rorkes Drift, and lost a lot of men, but held the final redoubt, even though the hospital was burned to the ground along with many of the patients. To this day that battle is considered a “textbook” defensive action. It is studied at Sandhurst and West Point. You can get the gist and feeling of the battle watching the movie Zulu (from which I got these photos of Red Coats), even though the movie got several minor details wrong.

The most unsung hero of the battle, on the British side, was the commisariat officer who suggested using mealie bags to build barricades. The road- and battle-weary Zulus attacked Rorke’s Drift till they thought they got their “Stay out!” message accross to the red-coated imperialists.

Sadly for the natives, the other British columns invading Zululand learned from Isandhlwana and Rorke’s Drift, and didn’t fare as poorly in the long run.

World War II: The Pacific

One notable exception to the “nobody stands against cold steel” rule is when the defenders have no place to go. In the Pacific (especially in the earlier years of WWII), the Japanese “Banzai!” charges were legendary, but failed to accomplish their goal of retaking the beachhead. The Marines stood their ground against the Japanese bayonets for two reasons:

- First, because they were Marines.

- Second, unless you could swim all the way back to Hawaii in your gear, or at least back to where Jeff Cooper and his boys were on their ships sending naval artillery over your head, retreat from the beach was not much of an option. Some soldiers of the overrun 105th Infantry regiment actually did swim from Saipan to offshore destroyers on 07 Jul 1944 (see below).

The so-called “Banzai charge” (Americans called it that after hearing the Japanese battle cry “Tennōheika Banzai!“) was an official part of Japanese military doctrine, but it had been more effective in the 1930s against Chinese troops with their bolt action rifles, than it was in the 1940s against the more rapid fire American BARs, M2s, .30 MGs, Thompsons, Garands, and M1 carbines.

The last major bayonet charge, Clint Smith noted, was on Saipan on 07 Jul 1944. It was a Hail Mary, all-hands-on-deck move. Several thousand Japanese, almost every single member of the surviving Japanese garrison, including walking wounded and even civilians–some armed with little more than sharpened sticks–charged the US troops in the wee hours of the morning. Hundreds of Marines and US Army soldiers were killed, and some American units were overrun, but virtually the entire Japanese force was wiped out. Most of the remaining Japanese on Saipan killed themselves by jumping off cliffs, rather than surrendering–despite impassioned pleas broadcast by American linguists on loudspeakers, in Japanese, that they would not be harmed.

The 4th Marine Division and the Army’s 27th Infantry Division bore the brunt of that massive bayonet assault. Google Private Thomas Baker, Capt Benjamin Salomon, and Lt Col William O’Brien to learn more about what it was like on the receiving end.

A handful of Japanese soldiers, including Capt Sakae Oba, who had lead from the front with a sword during the massive Banzai attack, escaped and evaded into Saipan’s interior, where he continued a guerrilla harassment campaign until months after the war ended.

Korea

On 07 Feb 1951, then-Captain Lewis J. Millett, who’d received a battlefield commission in WWII, saw that one of his platoons was pinned down by intense enemy fire from atop Hill 180 (now on Osan Air Base, South Korea).

To save them, Millett led two other platoons on a bayonet charge and took the hill, killing 50 Chinese (40% of them by bayonet). Millett was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Col Millett, who died on 14 Nov 2009, also served with the Rangers / Special Forces in Vietnam. His colorful exploits fall into the realm of “you can’t make this stuff up,” and are too numerous to list here.

Vietnam

Hand-to-hand combat, with knives, bayonets, entrenching tools, and even 5-gallon gas cans, was not entirely uncommon in Vietnam.

When US forces were on the offensive, the Viet Cong (VC) and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), collectively called “Charlie” (from the phonetic for VC, Victor Charlie) preferred to break contact, as any good guerrilla should in the face of an enemy with superior fighting strength.

“But on those rare occasions when we could pin them to a fight,” Army Special Forces SFC Gogurt told me in 1983, “they knew we had the artillery and the airpower, so they got real close, so we couldn’t use it on them.”

“That wan’t any fun at all,” he added.

When Charlie was on the offensive, it usually started with stealth. They used sappers to breach the defenses and infiltrate our outposts and fortified hamlets, most often at night.

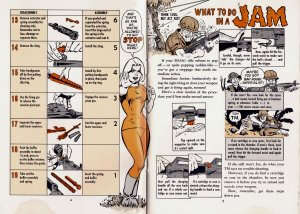

The brand-new M16 rifle had many reliability issues–due to changes in gunpowder, it’s direct gas impingement system, underpowered extractor springs, and the fact that Colt marketed it to the government as never needing cleaning, so the originals were sent out into the muddy jungles, river deltas, rice paddies, rubber plantations, and dusty highlands without complete cleaning kits (Clint Smith said all he got was a rod for the bore), or even maintenance instructions.

Disastrous under-maintenance led to harmful-over maintenance during the early ‘Nam era, as constant detailed disassembly of the lower receiver, pushing the steel pins in and out of the aluminum frame, enlarged the pin holes. Trigger and auto sear pins would suddenly fall out during fire fights (refer to Edward C. Ezell’s Great Rifle Controversy for more about the M16’s growing pains).

If the enemy is 50 meters away and your rifle quits, that’s bad enough. If he’s in the same hole with you when that happens, it’s worse. Here’s one example.

On 21 Jan 1968, Sgt Mykle E Stahl was running a mortar section on Hill 861, an outpost protecting Khe Sanh. The Gunny was dead, the First Sergeant was dying, and the Company Commander was too wounded to continue leading the Marines on the hill. The burden of command fell to 1Lt Jerry N Saulsbury, who despite his lack of infantry experience (he’d washed out of pilot training), rose to the occasion and acquitted himself well.

ALL Marines are riflemen first, and whatever their specialty is second.

Fortunately for the remaining Marines on Hill 861, Saulsbury had men like Stahl working for him.

Stahl, a Texan from Abilene, was already wounded by shrapnel when he saw that the leading trenches of their outpost were being overrun. Too close for his mortars to help, he moved forward and leapt into those trenches to rescue the wounded Marines there, facing off against 3 NVAs. One of the NVAs wounded Stahl (again) with a bayonet. Stahl’s M16 jammed, but he managed to kill 2 of the Charlies. Another Marine killed the third NVA.

Stahl “traded up” to an AK dropped by the NVAs and cleared the rest of the trench, killing 3 more NVAs, capturing 3 others, and re-taking a bunker. Despite being wounded a third time, Stahl then manned a .50 cal until the attack was repulsed.

As the mechanical reliability of the M16 (and then M16A1) was improved in fits and starts, the Army printed DA Pamphlet 750-30, a comic book designed to educate the GIs about how to get and keep their “Mattel Toy” up and running.

It was blatantly sexist and moderately racist (note the buck-toothed Charlie advising the Imperialist Yankee to check his ammo), but it was also humorous, informative, and caught the attention of the mostly adolescent GIs. The only mention of bayonets in DA Pam 750-30 was advice to use your M7 bayonet to cut .30 cal patches in quarters, if you couldn’t get any 5.56mm patches to swab your bore.

Falklands / Malvinas

According to Max Hastings & Simon Jenkins (The Battle for the Falklands, pp. 302 – 05), as the Scots Guards began their final assault on Mt Tumbledown, the Argentine 5th Marine Infantry Battalion met them with machine gun fire and snipers with night vision scopes. Major John Kiszeley determined to break the deadlock with a bayonet charge.

“Are you with me, 15 Platoon?” he yelled. The troops responded with a resounding . . .

Silence.

He repeated the question, even louder. One soldier replied “Aye.”

Another said, “Aye, sir, I’m f___ing with you as well.”

Turned out, the only thing scarier than facing cold steel is to BE the ones doing the bayonet charge. Especially uphill.

They took the summit, but at great cost to both sides. Kiszeley shot two Argentine soldiers and killed another with his bayonet.

According to Hastings & Jenkins (p. 299), and also Anthony H. Cordesman & Abraham R. Wagner (The Lessons of Modern War, Vol. III: The [Soviet -] Afghan and Falklands Conflicts, p. 285), Argentine soldiers also fell to bayonets on Mt. Longdon. See Appendix I for a controversy about bayonets on Mt. Tumbledown.

Iraq

On 14 May 2004, an unarmored convoy of Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders was ambushed by Shia insurgents not far from Basra in southern Iraq. It was a combined IED, mortar, rocket, machine gun and other small arms attack. Two of the British vehicles were disabled in the KZ (kill zone, or the X) of the ambush.

Soldiers of the Princess of Wales’ Royal Regiment (PWRR) rushed to their aid–and rolled into a classic, L-shaped ambush themselves.

The first Mahdi Army trenches were about 200 meters away.

Sgt David Falconer ordered the following men to fix bayonets and follow him:

- Sgt Chris Broome

- Private John-Claude Fowler

- Private Anthony Rushworth

- Private Matthew Tatawaqa

- Lance Corporal Brian Wood

They advanced in staggered rushes, straddling first one trench, then another, killing about 28 of the insurgents in fighting that became hand-to-hand. Three of the UK soldiers were wounded, but the other insurgents fled or held up in a bunker (till it was destroyed by a responding British tank).

Afghanistan

Corporal Sean Jones of 1st Battalion, Princess of Wales’ Royal Regiment, was on patrol in Helmand Province when his unit was ambushed by Taliban. They made it to a water-filled ditch, but were pinned down from three directions, surrounded by open terrain. It was just a matter of time before they were going to be wiped out, one by one.

Jones ordered three men with him to fix bayonets, and ordered two others to lay down covering fire, before sprinting over 80 meters of open ground.

I never did a bayonet charge, but once, near San Benito, Texas, I ran about 70 meters towards a shooter with an AR-15 who was gunning down my fellow cops, on a road that bullets had just bounced off of. Time did not seem to slow down, and I experienced zero auditory exclusion. In fact, the rifle (and returning pistol) fire was painfully loud. I did, however, experience spatial distortion: it seemed like my destination was a thousand meters away. It wasn’t till I went back later that I realized how short the distance really was.

It was over 10 meters farther, with easily three times the incoming fire, and it must’ve seemed like a hundred more, for Cpl Jones and the other men of 1 PWRR. Yet their gallant rush was so unexpected, it took the Taliban entirely by surprise. The Tallies bugged out. Jones was later awarded the Military Cross for his actions.

Dual Arming:

Replacing the Bayonet with a Pistol

In 2001, when I ran the arms room for Alpha Battery, 1/180 Field Artillery, AZ Army National Guard, we had over a hundred rifles, and several M60s, M203s, and M2s.

We had only ONE pistol: the commander’s Beretta M9.

For most of the previous century, the Army (and Marines) considered pistols officers’ scepters of office, or specialty weapons (for, say, a machine gunner to defend the emplacement if it is flanked and overrun).

In the first two decades of this century, however, the concept of “dual arming” has gained traction. More and more units are arming front line grunts and jarheads with pistols as well as rifles or MGs.

When I deployed in 1990, the Air Force let me carry a rifle and a sharp pointy thing every day. I only drew a pistol when I worked certain posts, was in plainclothes “downtown” (out on the economy), or carried the hog (M60).

When I deployed in 2008, the Air Force let me carry a rifle, a pistol, and a sharp pointy thing. Every day.

Yet, almost NO military training teaches our troops how to fire a pistol from the clinch, or how to retain it when it’s out of the holster. Hopefully, that will change. But that’s not even the main problem.

The hardware, whether its a rifle, a pistol, a bayonet, or all three, is just an accessory to the software. Our programming is what’s lacking.

The Air Force issued me close-quarters weapons, but every year, during computer based Anti-Terrorism (AT) training, I was specifically taught NOT to wrestle over a pistol that was stuck in my face, and rather instructed to surrender to the Tango because of his “superior firepower” (direct quote from the AT training system, telling me why I got it wrong–again–by answering I would wrestle him over the gun; the test was multiple choice, and “I would off-line it, control it, poke him in the eyes, execute a standard Krav Maga disarm, and insert it in the Tango’s rectum” was not one of the available answers).

On 27 Apr 2011, a green-on-blue occurred in the Air Command and Control Center (ACCC) at Kabul International Airport. One of the Afghan pilots we’d trained, and issued a pistol to, walked into the ACCC and gunned down 7 “armed” USAF personnel, plus an unarmed Army contractor, at close or contact range.

Most of those in the other rooms (outside the ACCC) who heard the shooting feared a suicide bomber and fled the building.

Only two who were in an adjacent room pulled their Berettas, chambered their top rounds, and went to the aid of their brothers and sister in the ACCC. Captains Bradley and Nylander made contact with the turncoat in the hall, and engaged him with pistol fire. They mortally wounded him, but one of them (Capt Nathan Nylander) was killed in the process.

Why didn’t ALL of the armed personnel who were in the building go to the aid of their ambushed comrades, or at least bunker down and wait to ambush the bad guy when he came into their workspace?

Mainly because they assumed the attacker had explosives. But also because they thought of it as their workspace, not their battle space.

It’s not a matter of courage. If they were wanting of courage, they wouldn’t have volunteered to be liaisons to the Afghan Air Force outside secured US compounds.

The bad guy started with one pistol. Six of the Air Force personnel in the ACCC had pistols. So did just about everybody else in the building. “Superior firepower” my ass. Improperly cultivated Warrior Souls.

I’m not speaking ill of any of the dead. All USAF personnel in the building were forced by stupid policy to carry their pistols half-loaded, in Condition 3 (nothing in the chamber). The one good guy in the ACCC with a rifle had recently arrived in country, and had yet to be issued any ammo for it–but he carried the rifle, just the same.

Their commanders had physically disarmed them, so they became mentally disarmed.

The KIAs were surprised, by a person they knew and perhaps even trusted. It’s also possible there was collusion by the other Afghans in the ACCC; there was certainly passive inaction on their part (none of the Afghans in the room were killed). The third investigation found no evidence of collusion, but I don’t know how many of the Afghans who had been in the ACCC they were given access to, or interviewed. According to one officer I interviewed who worked that mission, the Afghan witnesses were transferred to remote locations immediatey after, and the OSI investigators had little or no access to them.

I am calling out:

- Everyone in the chain of command who made or tolerated the stupid policy of carrying a partially loaded (or completely unloaded) pistol in a war zone, in direct contravention of their troops’ training (they were taught to draw and fire with a round in the chamber); and

- the people who created, approved, and implemented their white flag waving AT training. We need to be instilling the will to combat, not programming them to surrender to Islamist extremists who will not show them the tender mercies that Col Klink and Sgt Schultz gave to Hogan and his Heroes in that fictional television show.

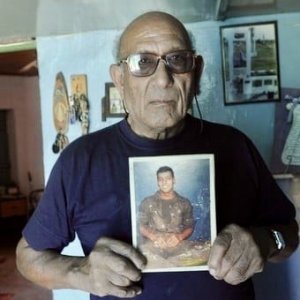

This photo is of Anwar Tarawneh, the widow of Jordanian pilot (and Sunni Muslim) Moaz al-Kasasbeh (his face is on the sign behind her). Captain al-Kasasbeh was shot down, captured, and burned alive by the godless savages of daesh near Raqqa, Syria.

Although the third investigation into the Kabul ACCC incident found “no lack of warrior ethos,” and that investigator was privy to more of the facts than I was, I cannot agree, based upon my contemporary experience as an AF small arms trainer, and the end results.

I guess it depends on your definition of “warrior ethos.”

If “warrior ethos” consists of being brave enough to expose yourself to great risks outside the wire (and in the air) in “the graveyard of empires,” where many of the same peoples who’d fought off the Soviets, the Brits, and Alexander the Great’s Macedonians hate you and want to kill you, they had it.

If “warrior ethos” means being technically competent at your job, your own particular cog in the giant war machine that is the US military, those air (and OSI) warriors had it in spades.

But if “warrior ethos” means readiness, being “switched on,” willing, and able to engage in close quarters mortal combat on an instant’s notice, any they had started with was programmed out out of them by our bullshit training, and the fact that their own commanders clearly felt that the weapons we issued them for only that purpose were more dangerous to them than to our enemies.

So even if they were all Audie Murphys, we stacked the training and equipment odds against them.

Bayonet Assault Courses are one way (of several) to develop that warrior ethos.

The Army Throws in the Towel on Bayonets

The Bayonet Assault Course was dropped from Army basic training in about 2010.

Bayonet training is relatively inexpensive (compared to, say, live-fire marksmanship training) but the powers that be deemed there were too many other competing demands for the basic recruits’ time. Gotta squeeze in all that important sensitivity training somewhere. Besides, they argued, hardly anybody ever actually uses a bayonet as a bayonet.

That line of thinking entirely misses the point.

As far as I know, bayonet training has not made a comeback in the US Army, at least not in basic training for all soldiers. It may still be a part of some infantry courses.

–George H, lead instructor, Heloderm LLC

*****

Appendix:

Who stabbed Marine Dragoon Galarza?

In 2014, The Guardian told the tragic tale of Falklands War vet Gordon Hoggan, who had been assigned to the 2nd Battallion of the Scots Guards.

Like many (BUT FAR FROM ALL) combat vets, Hoggan had some issues. He was haunted by his memories of the war, and had, for a period of time, been homeless.

One of his worst experiences, he said, had been stabbing an Argentine soldier in the neck with his bayonet.

The way Hoggan remembered it, he had approached the mouth of a cave on Mount Tumbledown and encountered two Argies within. He tried to shoot them, but at that moment his L1A1 SLR (Self-loading Rifle, their version of the FN FAL) quit. Reporters always say “it jammed,” but it may have simply run out of ammo without Hoggan realizing it. According to multiple Iraq tour (and US Army Ranger) Max M, “It’s impossible to count over 5 in a firefight,” and in the dark, Hoggan might not have noticed. When his SLR didn’t go “Bang,” Hoggan said he switched to plan B and gave the Argentine Marine the cold steel.

I don’t remember the Guardian mentioning the fate of the second soldier in the cave.

Hoggan said he took the helmet of the soldier he’d bayonetted as a war trophy (kinda morbid, but got to admit it’s more martial than the manufacturer’s plate off a Leyland AmBus). Decades later, he wished to bring some closure for both himself and the loved ones of the Argentine Dragoon he’d killed, by returning the helmet to the Marine’s family.

A touching human interest story, and it fit with the nearly universal media narrative that war breaks the souls of all participants, making them all, at best, future drug addicted homeless vets, and at worst, ticking time bombs who can go batshit crazy at any lone wolf moment.

PTS, not PTSD

The fact that the vast majority of veterans, while occasionally remembering the horrors they faced, return home to lead healthy, productive lives continuously escapes newscasters and script writers alike. The “Greatest Generation” that defeated Hitler, Mussolini, and Hirohito not only fathered all those baby boomers; their peaceful, productive labors propelled the US economy to heretofore unknown heights.

In September, 2021, before presenting at a Church Security conference, I had the privilege of seeing David Grossman speak, in person, for the second time. LtCol Grossman, a former Army Ranger and West Point Psychology professor, is a world-renowned expert on (among other things) the effects of combat on the human psyche. Grossman said that many war veterans experience post-traumatic stress (PTS), but only a small percentage develop PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

In little more than one generation we’ve gone from failing to acknowledge that PTSD exists to thinking that everyone in the military has it. I’m not sure which lie is a greater disservice to our veterans.

Probably the latter.

They appreciate our gratitude. They neither want nor need our pity.

Journalists from the Argentine news organization Clarin tracked down the family of the dead Dragoon, whose story was real enough. His name was Jose Luis Galarza, and he was assigned to the Argentine 5th Marine Infantry Battallion on Mt Tumbledown. He had been killed in the mouth of a cave he and another Marine had been using for cover.

Galarza’s story was even tied to that of an Argentine national hero, Petty Officer Julio Saturnio Castillo, who left his own cover to defend his two troops in the cave, and shouted some harsh words to the English before he was gunned down.

After The Guardian ran Hoggan’s story, though, several soldiers who’d been on Mt Tumbledown said it couldn’t be true. For one thing, Hoggan’s unit had not been ordered to fix bayonets before the final push to take the summit. There’s nothing to prevent a soldier deciding on his own to mount a bayonet on his rifle. It was dark, so how would others know? But in any event, they said, Hoggan’s unit hadn’t been near where Galarza and Castillo fell.

Actually sticking enemy soldiers with bayonets is so very unusual, every single known incidence is likely to have been thoroughly documented in after action reports (AARs). Apparently programmed by Hollywood to believe combatants get bayonetted all the time, the Guardian reporters didn’t corroborate Hoggan’s story with any official reports that I’m aware of.

Then again, not every event in wartime winds up on paper. Maybe Hoggan did exactly what he said, or maybe he’s been telling a comrade’s story for so long, he actually believes it’s his own.

I don’t even know for sure whether Galarza died of a bayonet thrust to the throat or the far more common high velocity lead poisoning (or steel shrapnel). There were way too many dead on both sides and the Brits, who were once again in possession of the islands when the smoke cleared, may have had “neither the time nor the inclination” to conduct thorough autopsies on every fallen soldier, sailor, airman and marine–even their own.

One thing is clear: Galarza died for his country and his family’s honor, and somebody killed him.