British P1907 / Japanese Arisaka / US M1917 Bayonets

The Short [detachable box] Magazine [fed] Lee – Enfield, or SMLE, was the standard infantry arm of the British Commonwealth armies for the first half of the 20th Century. Unlike the Mausers copied by just about every other military in the world, the SMLE’s locking lugs were in the rear, which may not have helped with accuracy, but certainly made their recesses easier to clean.

Unlike most other bolt action rifles, the SMLE cocked on closing, which made it easier to unlock and about 1/3 faster to cycle (but probably not quite as fast as the Swiss Karabiner Modell 1931, or K-31, straight-pull).

When adopting a bayonet to fit the SMLE, the British looked to the Japanese Arisaka rifle bayonet.

Bayonets were, and still are in many ways, throwbacks to medieval edged weapons warfare. The Japanese had recently “Westernised” many aspects of their culture, rapidly increasing industrialization, and adopting Western style uniforms and armaments for their military, but what peoples had a stronger and prouder edged weapons tradition than the Japanese? They had elevated sword making to high art, and swordsmanship to an almost spiritual quest for perfection.

Being affixed to the underside or side of a rifle meant a bayonet could not have the gentle, highly effective curvature of a katana–lest it sweep up in front of the muzzle and hence, the bullets.

Instead, the Arisaka bayonet’s point swept up till it was practically in line with the (necessarily straight) spine of the blade. There any resemblance to Japanese katana swords ended, as it did not have a tanto type tip, and the blade was fullered.

The same sword-length bayonet would mount on the Japanese Type 38, 96, and 99 Arisakas. So well entrenched was the bayonet in Japanese military doctrine, it could even be mounted to their Type 99 light machine gun (WHB Smith, A Basic Manual of Military Small Arms, 1945, p. 215)

One signature feature of the Arisaka bayonet was a hooked quillion, which is to say a long, forward curving extension of the lower guard (visible in the photo above).

There is some debate about the usefulness of a hooked quillion. Arguably, with practice and an obliging enemy, a Japanese imperial soldier could trap and perhaps even break an adversary’s bayonet (or sword) with a well-practiced and violent twisting motion.

Keep reading to learn about the downsides.

So enamored were the Japanese with the hooked quillion that they even mounted a forward curving quillion directly to the right side of their Type 44 rifles, which had a built-in, folding spike bayonet.

The British copied the hooked quillion, as well as the upswept, almost in-line-with-the-spine tip, and the short-sword length of the Arisaka bayonet in their pattern 1907 bayonets for the SMLE. The pattern 1907 was practically a clone of the Arisaka bayonet.

The hooked quillion of the P1907 got hung up on barbed wire in no man’s land, and theoretically would get hung up on foliage (had there been any left after the constant arterial bombardments of WWI), so they stopped making 1907s with the hooked quillion. Internet sources differ as to whether there was an official order to grind them off of existing bayonets, or whether armorers just did it because it made sense. Either way, it’s rare to find a pattern 1907 bayonet with a hooked quillion today.

The pattern 1907 bayonet in these photos is marked on the right side of the ricasso with a “broad band arrow” (the sides of the arrow mark sweeping down till they are about even with the end of the short shaft), which I understand is a proof mark indicating it has been inspected and found acceptable for government use. Below the broad band arrow are the letter X on the left and the letters OA on the right.

According to a commenter called “marysdad” on the firearmstalk forum (internet forums are dubious sources of information, but are occasionally an enlightening repository of otherwise esoteric oral tradition and lore), the X was a “bend test mark,” indicating the steel was tempered correctly.

Thus, the blade was not easily bent or warped out of shape. This was important because it was long and skinny and, like all bayonets, more likely to be used as a pry bar than for sticking in other men.

The OA indicated it was manufactured at the Orange Arsenal in Australia.

Australian pattern 1907 SMLE bayonets were made at the Lithgow Small Arms Factory in New South Wales from 1913 till 1927. They began making them again in WWII but moved production to Orange (Small Arms Factory number 3) in 1942. If your Aussie 1907 has an MA instead of an OA, it was made at Lithgow. See Worldbayonets.com for more information.

Wilkinson Sword of Great Britain made over 2 million M1917 bayonets during WWI, and over 10,000 during WWII.

The United States made a fixed internal magazine version of the SMLE’s cocks-on-closing action, the pattern 1914 (or P14), under contract for the British. By the time the Communists took over in Russia, freeing the Germans and their allies from a two-front war, the British had lost a third of their able-bodied male population. They didn’t need more rifles so much as they needed more men to carry them.

“There are only two ways left now of winning the war, and they both begin with A. One is aeroplanes and the other is America.”

–Winston Churchill, while British Minister of Munitions in WWI

That’s where we came in. The USA offered up our own young men to stand and even to advance where Frenchmen, Canadians, and soldiers from the rest of the British Commonwealth had fallen.

The Eddystone

When the US entered WWI in 1917, we were woefully unprepared to arm the growing number of American soldiers with our standard issue M1903 Springfield. US plants re-chambered their existing P14 barrel production from .303 British to the American standard .30-06 (the thirty caliber cartridge adopted in nineteen aught six).

The resulting .30-06 rifle was designated the US M1917 (not to be confused with the M1917 Colt revolver, or the M1917 Smith and Wesson revolver, the M1917 trench knife, the M1917 bolo knife, or the M1917 bayonet). Many M1917 rifles were made at the Remington Arms factory in Eddystone Pennsylvania, and so are sometimes called Eddystones (as the M1903 is often called the Springfield).

This American Enfield had really nice rear sights in a distinctive, high sided mount, plus a curved, very ergonomic bolt handle. Although Gary Cooper shot blanks through a Springfield M1903 (and a German Luger) in the 1941 film Sergeant York, the real Alvin C. York laid waste to the Huns with an M1917 (and an M1911 pistol) during the 08 Oct 1918 action that won York the Medal of Honor.

The bayonet for the M1917 was also, naturally, called the M1917 bayonet. Apart from the mortise, the slot for mounting it to the rifle, the M1917 bayonet was virtually identical of the British pattern 1907, which was itself an Arisaka bayonet clone.

Close Combat in the Trenches

The rifles of the First World War could hit a helmet poking over the lip of a trench several hundred yards away, but for trench raiding, closer quarters weapons were the order of the day (or more often, night).

E-tools

Erich Remarque said that the Germans preferred shovels (entrenching, or E-tools) to bayonets for trench raiding on the Western Front of WWI. See Entrenching Tools in Close Combat for details.

Knobkerries

The British had learned in the school of literal hard knocks–specifically, the Anglo-Zulu war of 1879–that something like a medieval mace (in principle, if not in construction materials) was an effective head-bashing tool. An impact weapon, even a pick axe handle, could be used on a drowsy German sentry as effectively as the Zulu iWisas had knocked British skulls out of their pith helmets in SE Africa.

The Blokes called the short, knurled ended African clubs knobkerries. The knobkerrie name stuck, even to the (often homemade or locally manufactured) clubs Tommies used for raiding trenches in WWI.

US M1917 / M1918 Trench Knives

The M1917 and M1918 “knives” were thin spikes with triangular cross sections. The were only good for stabbing, although there was a stirrup-like knuckle guard that wrapped around the wooden handle from the guard to the pommel, which could ostensibly be used as de facto “brass knuckles.” If you punched with the knife in hand, it would protect your knuckles while hitting the other guy harder than your fist.

The spikes were thin and often broke when submitted to torsional stresses, rather than longitudinal thrusts and withdrawals. In the real world, people who are stabbed in a fight may be turning or twisting away or fighting back, which requires a robust blade.

“Weapons should be hardy, rather than decorative.”

–Miyamoto Musashi, A Book of Five Rings

US 1918 Mark 1 Trench Knife

The Mark 1 was a set of “brass knuckles” or “knuckle dusters” with a thin, stiletto blade. According to Wikipedia the blade was patterned after the French Couteau Poignard Mle 1916 dit Le Vengeur (loosely translated, “Knife-Dagger, Model of 1916, for Vengeance). Various versions of the Mark 1 knife were issued to our troops for close combat while taking an enemy trench. Most arrived too late for WWI, but were issued in the early years of WWII.

The Mark 1 had a conical (spiked) pommel. The concept behind a conical tip is to focus all the kinetic energy in one point. These are frequently seen today in the auto parts section of stores, usually on a small hammer-like device for smashing one’s way through auto glass if trapped inside (be sure to strike the corner of the glass, not the middle). On a trench knife, the intended use was fracturing / penetrating skulls with “hammer” strikes, moving toward the pinkie side of your palm, opposite the direction you would move to thrust the blade tip first into someone.

The Mark 1 looked fearsome, but had several drawbacks:

- They were poorly balanced, with most of the weight in the bronze handle (some later versions / replicas had aluminum handles).

- While the blade was not as thin and flimsy as the M1917’s triangular spike, the blade’s ricasso narrowed near the guard, which was a weak point.

- They did not lend themselves to rapidly switching holds, from, say, a hammer grip to an ice pick grip. One advantage of edged weapons is (or, in the case of the trench knife, should be) that they can be multidirectional.

Trench Brooms

The Americans preferred a specific weapon for sweeping enemy held trenches: the pump-action riot shotgun. Specifically, the M97 and the M12.

The trench shotguns used in WWI were adapted to fit the existing M1917 sword bayonets–a somewhat intimidating combination.

The Enduring Legacy of the Trench Broom–and the M1917 Bayonet

The Winchester Model 1897 shotgun had first seen active service in the Spanish American war and the Philippine struggle for independence which followed. The range of buck (and bird) shot is limited to about that of a pistol, but it hit a lot harder. In thick jungles and tall elephant grass, long range shots were not common. It was not unlike elk hunting.

When I was first a rifleman by trade, and later when I was a park ranger, I lived in Wyoming.

When I was first a rifleman by trade, and later when I was a park ranger, I lived in Wyoming.

Elk hunting is the national sport of Wyoming, and several other Rocky Mountain states. I’ve hunted elk up in the black timber of the Snowy Mountains, and the Wind River range, and in Northern Arizona.

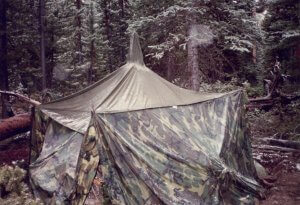

The pinewoods in the Savage Run wilderness were packed so densely that I once stepped a few feet out of camp to relieve myself, turned around, and couldn’t see our tent (it didn’t help that everything we used was issued equipment, in either OD green or woodland camouflage adopted for warfare in NATO Europe).

It’s said that an elk hunter either sees her quarry half a mile away, cresting a ridge across a canyon, or she stumbles upon an elk in the black timber, almost close enough to touch it.

That mirrored my experience elk hunting. Mostly, I didn’t see them at all, although I snuck within 22 meters of a medium sized bull elk with a bow in the pinion pines of Arizona. He stood broad-side to me, with water glistening majestically off his cape in the early morning sunlight. It would have made for a perfect shot–if I hadn’t drawn a cow tag that year instead.

Stumbling across you quarry almost close enough to touch them was often my experience hunting men in the thick, single canopy jungle lining the banks of the lower Rio Grande Valley. I was sometimes within feet of smugglers or smugglees–I could even smell them in the dark–but could only see them through the foliage by shifting my focus in and out, or by lighting up a flashlight to see a sudden splash of color–a red or yellow or blue jacket–through the green.

Jungle warfare in the South Pacific of WWII, and later in Vietnam, must’ve been something like that.

The difference was, I went home after my shift, showered, and dried out. Not so much with our GIs in the Pacific.

The close nature of the foliage–in the Pacific, Vietnam, and the Lower Rio Grande Valley–often called for close range weapons. See The Evolution of Police Long Guns for a story about my partner Travis Attaway, who was carrying a shotgun as we were laid-in by the Rio, when a smuggler stepped off the trail, and nearly stumbled over the top of him.

I’m sure there were some shotguns in WWII’s European Theater of Operations (ETO), but you don’t see too many pictures or read much about shotguns in the ETO. The WWI trench brooms made their real comeback–replete with M1917 bayonets–in the closely packed jungles of the Pacific Theater.

In the 1960s, the sons of WWII vets found themselves in Southeast Asian jungles. They had M16s, M14s, M79 grenade launchers, radios to call in airstrikes–and on rare occasions, dad’s (/ grandpa’s / great grandpa’s) Winchester M12 shotgun.

Not all of Vietnam is jungle, and most soldiers were issued rifles for reaching across rice paddies. The shotgun’s effective range was only about 35 meters. But there is a time and a place and a season for everything . . .

Thick vegetation was not the only reason Vietnam battles were often fought danger close. Like elk, the Charlies were either far away, breaking contact, or, knowing we had superior airpower and artillery, they got really close, so it couldn’t be used on them without endangering our own troops. A shotgun might be useful if enemy sappers leaped into your trench, mortar pit, or command bunker.

As the war in Southeast Asia escalated, old M12s were pulled out of storage and new shotgun manufacturing contracts were awarded. According to Leroy Thompson, shotgun toters in the USMC preferred the Winchester M12, the Special Forces preferred the Ithaca, and the USAF SPs preferred the Remington 870.

Rather than design a new bayonet, procurement officers ordered M1917s to be made according to their original specs, which somebody still had on file somewhere.

The main changes were plastic grip panels and a dull grey parkerized finish on the ‘Nam era M1917s. The ‘Nam ’17s also had two pins running through the guard and the tang of the blade, something not found on earlier M1917s.

General Cutlery of Fremont, Ohio and Canadian Arsenal Ltd of Ontario, Canada made sword-length M1917 bayonets in 1966 – 67.

Thus, as with the M1905 bayonet designed for the M1903 Springfield, the bayonet designed for the Eddystone rifle of 1917 was still in service in 1967 (and beyond), decades after the rifle it was designed for was rendered obsolete.

Later, US shotguns were modified to accept the same M7 & M9 bayonets that fit the M16 rifle.

–George H, lead instructor, Heloderm LLC