Baron von Steuben and Well Regulated American Volley Fire

Most Americans believe we won the Revolutionary war by sniping at the Redcoats from behind trees and boulders.

Not true.

Our troops did a lot of that, especially in the opening days of the war, when we were losing. Such so-called “guerrilla” tactics were little more than a nuisance to the British, one of the most professional armies in the world at the time. Distance and logistics played a large part, as did our eventual alliance with the French, but we did not begin winning till our rag-tag army learned to fight like professionals.

Volley Fire

In the 1700s, and well into the 1800s, that meant close-order drill and volley fire.

Most of my schoolteachers knew little of battle. Some were WWII, Korea, and / or Vietnam vets, but many of them had stayed in college as long as possible, specifically to avoid the draft, and wound up with advanced degrees only useful in academia.

My history teachers who fell into the latter category sneered at what they called “Gentleman’s Battles,” two armies standing in lines and firing at one another. That’s because they didn’t know what they didn’t know, and they tried to picture that through contemporary eyes. In the modern era of the rifled bore, bullets go where they are aimed, so “an army marches on its stomach”–because (as Firesign Theater pointed out) when they stand up, they get shot.

But the “Brown Bess” and other smoothbore muskets of the Revolutionary War era were slow to load, and incredibly inaccurate. Just as a pitched baseball does not fly in a straight line, there was no way to predict where that non-stabilized lead ball would go at any distance after slinging out of a non-rifled bore.

Even with 2 – 3 decades after our Revolutionary war to advance metallurgy and manufacturing methods, smoothbore muskets of the Napoleonic era were “not notably accurate beyond the length of three cricket pitches,” according to military historian Michael Glover:

“Most battles were decided by the musket which threw a ball weighing about an ounce and was inaccurate at more than eighty yards. Twenty drill movements were required to load and fire each shot and the practicable rate of fire was three or four rounds a minute. The musket was discharged by a flintlock which misfired once in seven rounds in dry weather. It was unlikely to fire at all in heavy rain. Only an exceptional flint would fire more than thirty rounds, after which it had to be changed.

With such a weapon the only way to stop an advancing enemy was to draw up the troops shoulder-to-shoulder and fire repeated volleys. In this way some of the musket balls were bound to find a mark among the enemy who, for the same reason, would also be shoulder-to-shoulder. Given equal discipline and morale, the advantage would go to the side which could bring the most muskets to bear and could fire the most volleys.”

—The Peninsular War 1807 – 1814, pp. 9, 31 – 32

Incidentally, in case you find yourself on Jeopardy, a regulation cricket pitch is 66 feet.

Rifled barrels did exist during the American Revolution, but they were far fewer than smooth bore muskets, and took twice as long to reload.

Simply put, the only way to hit anything with the smooth bore muskets used by both sides during the Revolutionary war, or to keep up any significant volume of fire, was to fire in volleys with your comrades, then reload while those who had been behind you stepped up and fired their volleys.

Without training, shooting and reloading with five foot long, muzzle-loading muskets around other people would be dangerous slapstick at best. At worst, it would get you and your teammates killed.

“. . . among close-packed groups of men equipped with firearms, one’s neighbour’s weapon offers a much more immediate threat to life than any wielded by the enemy.”

–John Keegan, discussing “friendly” fire the evening of Waterloo, in The Face of Battle (p. 193)

To get the timing and critical positioning right, soldiers needed to practice close order battle drill extensively.

Volley fire was the 18th Century equivalent of the modern assault rifle, which is intended to produce a large volume of fire to keep enemy heads down as soldiers advance upon (“assault”) an enemy position.

If you want some idea of the effectiveness of volley fire, watch the movie Zulu–although that portrayed a century later, with rifled breechloading Martini cartridge guns, in the desperate defensive battle at Rorke’s Drift. Rorke’s Drift was a small, vastly outnumbered (<150 Brits vs 4000 or so Zulus) mission station in Natal, on the border of Zululand.

Zulu was filmed with the assistance of descendants of the natives who fought in those remarkable 1879 battles. Although several of the fighting sequences are somewhat cheesy by modern, CGI- and blood squib-enhanced standards, it’s still a great film. It was Michael Caine’s breakthrough role. They don’t write dialog like that anymore. Here’s a period appropriate, realistic sample, from when they’d just received news of the complete Zulu victory at Isandlwana:

Lt. Bromhead: The entire column [annihilated]? It’s damned impossible! Eight hundred men?

Adendorff: Twelve hundred men. There were four hundred native levies, also.

Lt. Bromhead: Damn the levies, man, more cowardly Blacks!

Adendorff: What the hell do you mean, “cowardly Blacks”? They died on your side, didn’t they? And who the hell do you think is coming to wipe out your little command? The Grenadier Guards?

Enter Baron Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand von Steuben

A century before Rourke’s Drift, when what was left of our Continental so-called Army was starving at Valley Forge, Baron von Steuben, a trained and experienced Prussian general staff officer, arrived to lend a hand.

A century before Rourke’s Drift, when what was left of our Continental so-called Army was starving at Valley Forge, Baron von Steuben, a trained and experienced Prussian general staff officer, arrived to lend a hand.

He started out with sanitation, introducing the concept of the latrine, and placed the latrines on opposite sides of the camp (and downhill) from where the food was cooked. Then he drilled our boys in how to move as a unit, how to fire and load in volleys, and how to use their bayonets. Later, von Steuben wrote Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States, our first military manual (that was our Army’s official combat doctrine, more or less unchanged, well into the next century).

Regulations was NOT, as you might otherwise guess from the modern meaning of that word, just rules, like “Don’t poop where you eat.” Regulations was a How-To manual for close order battle drill: how to load your weapon, how to do volley fire.

After the Revolutionary war, the United States practically disbanded the Continental Army, but every town and village had a militia. It wasn’t a paid, voluntary specialty like being in the Air National Guard. Every able-bodied adult male was expected to be part of the militia, ready to respond in the event of hungry wolves, marauding highwaymen, Native Americans who wanted their land back, and other emergencies.

Armed citizens who knew and practiced their Regulations, how to act as a team producing effective volley fire, were considered “well regulated” in the American English of the 1780s.

Does that phrase sound familiar?

Incidentally, during the Revolutionary War era, many towns required that 1/3 of their militia be Minutemen, capable of responding to disorder or emergency in one minute or less.

Well Regulated Shoulder-to-Shoulder Infantry vs Cavalry

Standing shoulder-to-shoulder also helped protect foot soldiers and militia against cavalry charges.

Although we see digitally created horses charge into “shield walls” all the time in action movies, real horses, even well-trained war horses, will not charge at full speed into what they perceive to be a wall. They might jump over men or run between them, but they would pull up short when they come up against riflemen who were drilled (“regulated”) well enough to stand their ground, shoulder-to-shoulder, in the face of such a daunting charge.

Especially if the “wall” was bristling with bayonets on very long rifles

The Demise of Shoulder-to-Shoulder Volley Fire

Close Order drill, as practiced in the 18th and 19th Centuries, is no longer a viable fighting technique.

Volley Fire was still occasionally ordered during the Spanish American War and the subsequent Philippine American War, mostly out of habit (“military change is evolutionary, not revolutionary”). After taking “Kettle Hill” (one of the two lomas de San Juan), Teddy Roosevelt directed his men to “lay down volley fire” across the valley between Kettle and San Juan hill, to keep Spanish heads down in support of Hawkins’ attack on the south end of San Juan. The Roughriders and regulars with Roosevelt lifted their fire as Hawkins’ brigade took their objective. Then Roosevelt, who had to dismount from his horse “Little Texas” at a wire obstacle on Kettle Hill, led troops across the valley on foot to seize the north end of San Juan hill.

Volley Fire was minimally effective then, and would have been useless in the machinegun fire raked No-Man’s Land of WWI. A set of military drill regulations published after the First World War stated:

Fire by volley [now] has limited uses. It is used mostly at military funeral ceremonies to fire the three volleys over the grave of the deceased. Its uses during battle will be covered in the subject of combat principles. The platoon and section are the only units that ever fire by volley in combat.

—Infantry Drill Manual, p. 121

Nail 1 in the Coffin of Volley Fire: Rapid Fire

Earlier, in the 1840s, Texas Rangers pursuing Comanche raiders had difficulty reloading their muzzle-loaders from horseback. They made the mistake of dismounting and forming lines, often to do volley fire, sometimes forming square on the open plains, and sometimes firing from cover such as a riverbank. While the Ranger volley fire was more effective than not firing in volleys, the mounted Comanche riding around them could fire 20 arrows from horseback, even shooting behind them, in the time it took the Rangers to fire 3 or 4 shots from their muzzle loaders. Further, the dismounted infantry had difficulty hitting the widely dispersed Comanche warriors who were moving at a gallop across their field of fire, rather than straight at the Rangers. The Plains Wars led directly to the adoption of the revolver, which could deliver multiple shots from a moving horseback before needing to be reloaded.

These days, rifles are self-loading, and reloads take seconds instead of half a minute.

The rapid fire revolution, first with revolvers, then breech loading cartridge guns, then magazine fed, manually operated turn-bolt action rifles, then semi-auto pistols and rifles, then selective fire (semi- or full-auto) rifles and machine guns, meant you didn’t have to shoot at the same time as the buddies in your rank to maintain a relatively high volume of fire. “Fire at will,” meaning whenever you have an enemy in your sights for a brief moment, took the place of firing simultaneous volleys upon command, whether you have a viable target or not.

Nail 2: Accurate Fire

The second nail in the coffin of Volley Fire was the rifled bore. Spin-stabilized bullets pretty much go where they are aimed. Standing close together means that bullets fired in your direction are going to hit somebody.

“. . . every time you salute the captain you make him a target for the Germans. So do us a favor, don’t do it. Especially when I’m standing next to him. Capice?”

–“Pvt Caparzo,” Saving Private Ryan

Soldiers maintain some distance between themselves now, if they have room. “Extended Order” (as opposed to Close Order) has been the battlefield rule since World War I. Even while grudgingly accepting the occasional necessity for volley fire, the manual quoted above (and below) states that volleys may be shot “in any firing formation,” including the then combat-mandatory Extended Order (i.e., spread out in a skirmish line).

But you should still learn to work and fight in close proximity to your loved ones, unless you live in a mansion or an open field. “The Wave” and other drills to raise your subconscious awareness of your muzzle direction are essential if you are going to work with a gun out in close proximity to other friendlies.

Why Marching Drill Lingers

Our present regulations are based upon our latest experiences in the [First] World War, as well as upon all previous experiences. They have stood the test of time and have proven sound. The importance which they attach to discipline, precision and thoroughness, are based upon thousands of years of experience in training men for war. Therefore, let us have confidence in and closely study the regulations.

—Infantry Drill Manual, 12th ed (1928), Ch XXVIII, “Hints to Drill Instructors (the Regulations are Sound),” p. 211

Heloderm Range Safety Officers Terence and Martin rode to battle in mechanical conveyances. Taylor “rides” his engine of war to battle from the other side of the planet, every day. But marching as a unit is still one of the first things we learn in basic training, regardless of your branch of service.

Why?

It’s not just ridiculous adherence to meaningless tradition (although I thought so when they did it to me). It’s so you learn how to operate as a team. Basic trainees, NCO leadership school attendees, ROTC students and service academy cadets learn how to march and then (with the exception of the basics) take turns giving commands to their marching classmates, as a means of learning how to follow, an essential prerequisite of learning how to lead.

Von Steuben and the Why

Von Steuben found teaching Colonials quite a challenge. According to P. Lockhart, von Steuben wrote in his diary:

“In Europe, you say to your soldier, ‘Do this’ and he does it. But I am obliged to say to the American, ‘This is why you ought to do this,’ and only then does he do it.”

–The Drillmaster of Valley Forge: the Baron de Steuben and the Making of the American Army, quoted by the Dolan Consulting Group

Without von Steuben’s contributions, we might be His Majesty’s* subjects to this day. His influence lives on in other ways (not just when Ferris lip sync’ed “Shake It Up Baby” during a Chicago Von Steuben Day parade). The Baron teaches us how to be good instructors, even now.

“Any trainer who isn’t giving you the why really isn’t helping you at all.”

–Jeff Gonzales, former Navy SEAL

When you teach a skill, make sure you have a better answer for “Why?” than ” ‘Cause that’s how we did it in the __________.”

Make sure the skills you choose to teach fit both the environment your students are training for, and the skill levels they can attain in the limited time allotted for training with that team.

Baron von Steuben’s reasoning made its way into drill regulations published a century and a half later:

The American likes to know the reason for everything that he is required to do. Blind obedience, the belief that it is not his place to “reason why,” is not characteristic of the best type of soldier. There is a reason, and a good reason, for every movement prescribed in the regulations. If the instructor will explain these reasons he will win the confidence and support of his men. They will take pride in performing movements exactly as prescribed when they appreciate the reason, and the progress of the instruction will be rapid. They will seldom ask questions, and the instructor must anticipate and answer the unspoken question, “Why?”

–Infantry Drill Manual (12th ed, 1928), p. 213

Baron von Steuben’s Legacy

For many years, Americans in many towns celebrated “Von Steuben Day” in mid-September (the baron was born on 17 Sep). The holiday was big especially among German Americans, and had an “Oktoberfest” feel. It’s still celebrated in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago (although they skipped 2020, for COVID isolation).

Many Americans have short attention spans and even shorter memories. Most of those ogling Miss German America during a Von Steuben Day parade neither know nor much care about what von Steuben did for us. Fewer still understand how “well regulated” became part of our constitutional lexicon, or what it really means.

But the baron is making somewhat of a cultural comeback on another front. Friedrich von Steuben preferred the company of men. While there is no conclusive evidence that he was (he lived way before children were required to decide and declare their sexuality in elementary school), it is possible, perhaps even likely, that von Steuben came to America, at least in part, to escape persecution for being homosexual. Gays in uniform can look to von Steuben as, potentially, one of America’s first LGBTQ+ military heroes.

For many years, the very definition of American was someone ether forced out of their own country, or dragged away from it by indentured servitude or slavery. The USA is a nation of immigrants, most of whom sought a better life than they could find at home.

Even if von Steuben hadn’t contributed immeasurably to our mutual independence, the fact that he came here seeking his own, the right to be left alone to govern his own affairs as he saw fit, made that Prussian general as American as one can get.

–George H, Lead Instructor, Heloderm LLC

Epilogue: The Return of Volley Fire

Volley Fire came back in the 1970s, though not in its original, advancing, standing shoulder-to-shoulder form. The “Simultaneous Shot” technique is now used by police or Spec Ops snipers to take out several hostage takers at once.

The unit later designated GIGN successfully used a simultaneous volley to take out all but one hostage taker during the Loyada school bus rescue of 04 Feb 1976 (see Bus Takedowns).

Israel’s Yamam counter-terrorism commandoes used a simultaneous volley to take out terrorists aboard the “Mother’s Bus” on 07 Mar 1988.

More recently, on 12 Apr 2009, SEALS fired a simultaneous volley to take out the Somali pirates holding Captain Phillips hostage.

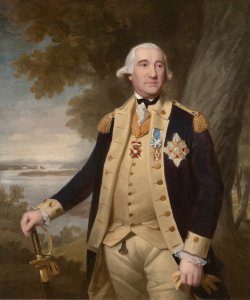

Most of the material in this article was taken from the protected post RSO Instructor Development 19 Dec 2020, in the Alumni Only section of this website. Featured image of Baron von Steuben is from the National Park Service (NPS.gov).

*When I first wrote this article, it was Her Majesty’s subjects. Rest in peace, Queen Elizabeth II.