Grip, Hold, and Stance

What’s the difference, when they matter, when they don’t, and why you must have several in your repertoire.

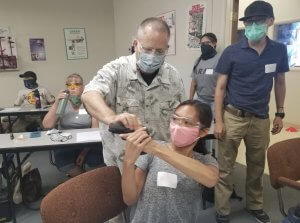

Some of this was written for the training summary of our 10 Oct 2020 Pistol fundamentals class, specifically addressing aspects of grip, hold, and stance that we covered that day. This version of that narrative has been substantially expanded to encompass most of the major schools of thought regarding how to hold a pistol.

Training summaries are written for our alumni, but we’re posting this publicly in the Intel section to give everyone who visits this site the opportunity to get a broader background on what we train and why.

First, a few definitions and concepts:

Below line of sight fire: Shooting from bent elbow / retention positions, usually at close contact range, where the sights cannot be used.

Bent elbow fire: Shooting with the gun-side elbow bent, usually for retention purposes. Could be angled down (in retention) or up (to prevent shoot through issues). A type of compressed hold.

Beyond line of sight fire: Shooting from an angle where the sights are not on a line between you and your threat. Below line of sight fire is one type of beyond line of sight fire. In beyond line of sight fire, the gun may also be at or above eye level. With pistols, this could be reaching around a hostage’s head to for a contact shot on the hostage taker, or reaching around your spouse who is rolling around on the floor in the clinch with a home invader. With long guns, beyond line of sight fire can be with the stock over the shoulder, say when scanning over the lip of a dumpster in clearing operations. With either, it could be reaching across to shoot down through a windshield (say, you were putting away the shopping cart when a guy jumps in your car and is about to drive off with your kids).

Bladed stance: Standing with your support side toward the target, as if snowboarding or riding a skateboard. Preferred in some martial arts. Before rifle plate body armor was common, police academies taught the bladed field interview stance, a way to keep one’s strong side hip holster away from suspects when talking with them on a street corner.

Bore line: An imaginary line running down the center of the barrel and out the front of the gun. We use the term primarily to illustrate concepts when referring to exterior ballistics, what the bullet does after it leaves a barrel (the trajectory, another invisible line, is an arc that starts along the bore line at the muzzle and drops off from there). A rearward extension of the bore line runs through the firing pin channel in the middle of the slide and out the back of the gun. When discussing Grip and Hold it’s important to remember that the higher the bore line is above the hands holding the pistol, the more leverage the recoil will have to flip the pistol up after it is fired.

Brewing fight: A fight where you have some prior indication that trouble may be coming. Brewing fights may initially involve deception on the part of the perpetrator. If you read the signs correctly, you have time to be more proactive when the fight is brewing.

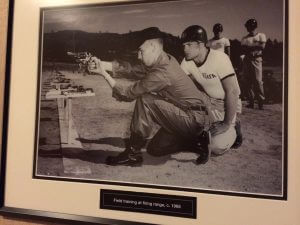

CATM: Combat Arms, Training, and Maintenance. Air Force small arms instructors and repairmen–the “Red Hats.” Formerly SAMTU (Small Arms Maintenance and Training Unit). For many years it was its own career field; kids who shot well in basic training might be recruited into SAMTU / CATM to teach other Airedales how to shoot, without ever having used or carried firearms outside a firing range. In the 1980s there was a push to make CATM training more “tactical” and less marksmanship oriented; to which many CATM instructors replied, “As soon a you give ME some tactical training, I’ll be glad to pass it on.” For that and other reasons, in the 1990s, the Air Force made previous experience in the Security Forces (to at least a 5 skill level) a prerequisite for assignment to CATM (I believe it recently converted back to a separate career field, one recruits can get into right out of basic training). About that time, the name was shortened to simply CA, although they still repair firearms in addition to teaching and qualifying USAF personnel to carry guns. Not to be confused with what the Army calls “combat arms:” combat troops such as infantry, armor, and artillery.

Center Axis Relock (CAR): A bladed, close range shooting system developed by Great Britain’s Paul Castle. As the body pivots around one’s vertical center axis, you re-lock your support hand further around the front of your gun hand.

Clinch: A fight at grappling distance. Like freeways, often used in conjunction with “the,” e.g., ” . . . when in the clinch.” Spelled with an e (“clench”) in some of the literature.

Close contact distance: Within two arms’ reach of your opponent (about 2 meters). Where most crimes, and most pistol fights, take place. Given that bad guys use deception to get closer, or can put on a sudden burst of speed to close the distance, close contact holds should be used within 3 meters.

Compressed hold: Shooting from something other than full arm extension. A continuum, from moderately bent elbows to one handed retention holds by the ribs.

Contact weapon: An instrument, such as a knife or club, that requires proximity, permitting direct contact between the weapon and the recipient, to injure.

Flash fight: A fight that starts before you realize you are in a fight. Your initial actions in a flash fight are reactive, rather than proactive.

Grip: How your hand(s) interface with the pistol. Alternately, when naming the parts of a pistol, the grip or grips are the part of the pistol frame that your hand holds, usually containing the magazine well.

Gun hand: The hand attached to the finger that pulls the trigger. Usually, but not always, your “strong,” or dominant, hand.

Hold: How your arms and hands work to control recoil. Most recoil is perceived after the bullet leaves the barrel, so recoil control has nothing to do with marksmanship. It is, however, important to speed up follow-on shots. Since almost all bad guys require multiple pistol hits before stopping their aggression, rapid follow-on shots can be very important.

Point shooting: Aligning the pistol with the target using arm or body indexed methods, rather than the sights. The pistol is almost always brought up into the line of sight between the shooter and the target, but the eyes are focused on the target.

Sighted fire: Aligning the pistol with the target using the sights. Happens most of the time on the range, but only rarely in an actual fight, for multiple reasons. Sighted fire is essential at longer ranges, or when the target is small (for example, ankles under a car), or in some hostage situations.

Stance: What your feet, legs, and torso are doing when you shoot. When most people say the word “stance,” though, they often use it to include aspects of hold and grip as well. CAUTION: The word “stance” implies “stand,” as in one place, which may be a bad idea in a fight.

Support hand: The hand that does not need to be on the pistol. Usually, but not always, your “weak” or non-dominant hand.

Tang: The curved upper rear portion of a pistol’s frame or lower receiver, just below the slide. Not to be confused with the tang of a knife, which is an extension of the blade that fits into the grip allowing the grip to be attached to the blade.

Target focused shooting: Keeping both eyes open, focused on the threat, rather than any part of the pistol. Likened to throwing a ball at a basketball hoop–you look where you want the ball to go, rather than at the ball, as you do it. Essential in point shooting, but also best when using reflex sights such as the Trijicon RMR.

GRIP

Grip, again, is how your hand(s) interface with the pistol.

When two-handed pistol shooting became the norm, a few different grips and holds were tried. For example, in 1973’s Live and Let Die, you can see Roger Moore as 007 holding his gun hand WRIST with his bent-elbow support hand to steady his aim. This did not remain popular for long. Among other things it worked better with revolvers than it did with semi-auto pistols. The slide of semi-autos reciprocates back over the shooting wrist rapidly enough to cut the thumb of a hand holding that wrist.

When the USAF first taught me to shoot the Smith and Wesson Model 15 in 1981, a “cup and saucer” grip was encouraged.

Now, we discourage cup and saucer (resting the gun hand ON the palm of the support hand), as it does little to control recoil. C&S simply gives the gun hand something to bounce off of. Instead, wrapping the support hand around the front of the gun hand is the current state of the art.

Ideally, your grip is high up on the pistol, with the web of your gun hand thumb in contact with the tang, the curved back part of the grip just below the slide. Every action has an equal and opposite reaction. The force that pushes the bullet out of the barrel also pushes back on the case in the chamber, along a line (the “bore line”) running through the center of the barrel and back through the slide. The closer your hand is to that bore line, the less leverage the recoil will have to flip your muzzle up.

With a semi-auto pistol, it’s very important to have both of your thumbs on the same side of the handgun. Wrapping your support hand thumb around the back can get it in the way of the reciprocating slide. This can cut your hand, but more importantly can also induce a stoppage. “Stacking” your thumbs like in this picture works well for most people with most pistols.

Sometimes right handed people with stacked thumbs accidentally bump the slide catch up during recoil. If that is a persistent problem with your hands / pistol combination, you might want to place your gun hand thumb outboard a little onto the support hand thumb. If your pistol has an external manual thumb safety, you could rest your gun hand thumb on the safety, and the other thumb on top of that.

In a perfect world, when all of us would have big enough hands, your grip should find the slide of the pistol in line with your forearm. That makes it easier to point naturally at our threat, whether we are using the sights or not. With some pistols (for example the Beretta 92 / 96 series, including the M9), people with smaller hands may have to come at the grip from 5:30 (or, for lefties, 6:30) rather than 6 o’clock, in order to reach the trigger.

Grip may or may not matter. Consistent grip is very important in competitive shooting, and it can be very useful in proactive situations where marksmanship is paramount. An example would be if you are NOT being directly targeted (the bad guy is currently shooting at someone else) and you need to take out an active shooter some distance away. That’s when all the fundamentals, including grip and stance, can make a difference.

In reactive situations, attaining a perfect grip may not be your highest priority. Maybe your spouse got the pistol knocked out of his or her hand wrestling with the bad guy, and you are snatching it off the ground for a very rapid close range shot. Don’t stop to analyze your grip. It will be what it will be.

THE MOST FUNDAMENTAL PISTOL FUNDAMENTALS

Regardless of your theological outlook on Jesus of Nazareth, who was a very real person mentioned in historical documents from the early first millennium, you will probably understand his philosophical wisdom in distilling the entire Law of the ancient Hebrews into “Love God” and “Love your neighbor.” Similarly, pistol marksmanship can be distilled into “Align the pistol with the target” and “Press the trigger in a way that does not disturb that alignment.”

Everything else is merely nuance.

A proper two handed hold on the pistol can help you do that, and can also help you control recoil for rapid follow on shots, but it is only one part of your shooting platform, and one part of a much bigger picture.

If you are talking on a cell phone to the 911 operator when the bad guy suddenly rallies, or you are half-dragging your wounded spouse, or carrying your young child with that support arm, where you might otherwise be placing your support hand on your pistol is irrelevant.

We spend a lot of time on grip in Fundamentals clinics, because grip is, well, fundamental. But don’t fret if your hands are shaped slightly differently, or your pistol is too big or too small for your hands to hold it exactly the “textbook” way we do.

STANCE

As Warlizard Tactical instructor Michael G points out, “stance” implies “stand,” which may or may not be the thing to do in a gunfight. All fights begin as ambushes. If you are the ambushee, exiting the kill zone (getting off the X) takes priority over return fire, or even getting your gun out (if you try to draw and then run, you WILL be shot; instead, run NOW and then start your draw). When you get around to returning fire, it may be from a full sprint and therefore approximate at best, at least at first (keeping in mind that your are ALWAYS responsible for the final resting place of every bullet that you launch).

Ideally, if you are standing in one place, your weight should be slightly forward on the balls of your toes, rather than your heels, with a slight flex to your knees, to help you manage recoil in rapid shots. Again, that only applies if your feet are stationary.

WHAT IS YOUR STANCE TELLING HIM?

Most communication is non-verbal, and communicating with defensive display of a firearm is no different. Leaning back away from the pistol (using your torso to cantilever it up) conveys the message “A stiff breeze would knock me over. Don’t worry about this gun; I’m afraid of it, actually. Go ahead and rape me.” An aggressive, forward stance with weight on the balls of your toes says “You don’t want any part of this. I can, and I will. Go rape someone else.”

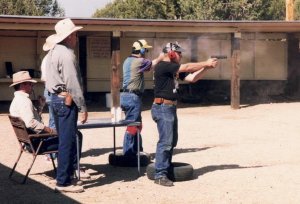

Which of these stances says “don’t mess with me” better?

The aggressive stance of this shooter in the purple shirt is a bit overboard, but you are much more likely to deter aggression with something akin to that, than with the passive stance in the photo above it.

HOLDS

Holds are what you do with your arms. Where your legs are and what they are doing can affect the way you hold the pistol. What you do with your hands also affects what you do with your arms.

Your grip, your hold, and your stance combined make up what we call your shooting platform.

The two most common ways of holding the pistol with two hands have been Isosceles and Weaver, although Center Axis Relock (CAR) is gaining popularity.

ISOSCELES

Both arms are held out equally, more or less straight, forming an isosceles triangle with your chest. Your belly button points straight at the target.

Because your “support” (weaker) hand will be wrapped around the front of the pistol grip, an inch or two ahead of your “dominant” / “strong side” / “gun side” hand, it helps if your support side shoulder is an inch or two forward. To facilitate this, it can help if your support side foot is at least a few inches ahead of your dominant side foot.

Because the arm position lacks leverage, Isosceles depends in large part upon a forward leaning stance to control recoil. We will get into other aspects of Isosceles (see Isosceles Makes a Comeback below), after we give you a hold to contrast it against: Weaver.

WEAVER

The support arm is bent, with the elbow DOWN. The gun arm is straighter (how straight it is has morphed over time; see below). The support hand pulls the gun arm back into the dominant shoulder like the stock of a rifle. The gun hand pushes forward against the pull of the support hand to create isometric tension. This tension is the raison d’être of Weaver.

I had first heard about Weaver from my friend (and later ATF agent) Scott S in the late ’70s or early ’80s, but I didn’t understand its principles or the reasons behind it until I worked at a pistol range from 1984 to ’86. There, I took intro and intermediate level Defensive Pistolcraft courses taught by a Gunsite grad. Weaver was part and parcel of Jeff Cooper’s Modern Technique of the Pistol, which was the methodology taught at Cooper’s Gunsite ranch (see API below).

When I went back on active duty as a Security Policeman in the AF, they were still teaching Isosceles.

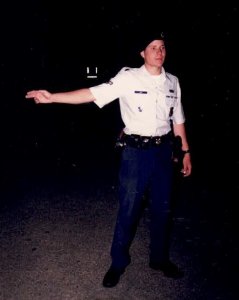

On 28 Aug 1986, I asked my USAF small arms instructor if could shoot my issued .38 revolver from a Weaver hold. She didn’t know what “Weaver” was. Two years later, Weaver became official USAF pistol doctrine.

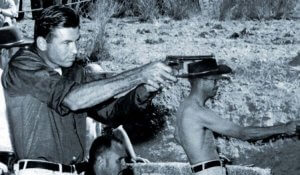

Here I am directing traffic with “”Gorman,” my issued Smith & Wesson Model 15-3 revolver (sn K870537), ca 1986. Dump pouches to the right of the SAC belt buckle contained 6 PGU-12/B cartridges each, in Bianchi zip strips, in addition to the 6 in the gun.

PGU-12/B was a USAF proprietary cartridge. The projectile was a 130 grain FMJ, like M41, only pushed deeper into the case with a heavy roll crimp over the ogive. This resulted in +P or even +P+ velocity, with commensurate recoil, but was easily controlled by a Weaver hold (when the CATM instructors let me).

“MODIFIED” WEAVER

In order to understand what people mean by Modified Weaver, you should know a little about the history of your art, especially in the 20th Century.

Pistols were originally one-hand guns used to keep cavalry riders from being unhorsed. Riders held the reins in the other hand. On 02 Sep 1898, cavalry Lt Winston Churchill, who found himself up to his thighs in Ansar (“Dervishes”) in the khor (arroyo) at Omdurman during the charge of the 21st Lancers, fended them off with his broom handled Mauser:

“Then, and not till then, the killing began; and thereafter each man saw the world along his lance, under his [saber] guard, or through the back sight of his pistol…”

–Winston Churchill, The River War

A lot of things happened in the pistol world over the next sixty years, primarily in the realm of crouched “point” shooting. We will address those methods under ONE HANDED SHOOTING below. For now, let’s just say that even policemen were taught to shoot handguns almost exclusively one handed, unless the threat was a long ways away, as recently as the early 1970s.

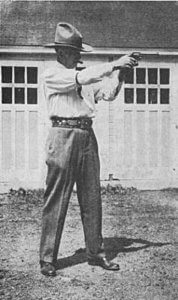

One historical tidbit germane to this part of the discussion is that in 1930, John Henry FitzGerald published a book called Shooting. On page 363 of that book, “Fitz” can been seen in a bladed, bent support elbow stance we now call the “Weaver” (Cassidy, Quick or Dead, pp. 78 – 79). However, that hold was not widely known until the 1960s & ’70s.

One historical tidbit germane to this part of the discussion is that in 1930, John Henry FitzGerald published a book called Shooting. On page 363 of that book, “Fitz” can been seen in a bladed, bent support elbow stance we now call the “Weaver” (Cassidy, Quick or Dead, pp. 78 – 79). However, that hold was not widely known until the 1960s & ’70s.

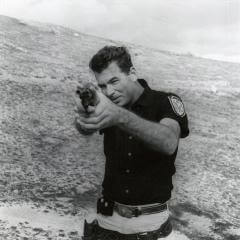

Jack Weaver was a Los Angeles County Deputy and competitive shooter who arose to national prominence as a shooting champion in the late 1950s. But it was his exploits, or should I say his shooting style, in the “Big Bear Leatherslap” action pistol matches of the 1950s and early ’60s that made his name a household word in the pistol shooting world. Weaver shot with BOTH arms bent, although the support arm was bent more, in order to lock his revolver into a vise-like grip between his 2 opposing hands. He was the first ever to win the Leatherslap match using two hands, in 1959.

Ray Chapman, one of the founders of the International Practical Shooting Confederation (IPSC), mimicked Weaver’s isometric tension but simplified the hold by firing with a straight gun arm. In 1975, Chapman won the first IPSC Handgun World Shoot in Zurich, Switzerland, with that straight arm, pulled in tight by his bent support arm. Chapman taught that hold at his Chapman Academy of Practical Shooting (I met him there on 26 Jul 1993, when I passed through Missouri), and his hold / stance became known as the “Chapman Modification” of Weaver.

Lt Col Cooper, “the father of modern pistolcraft,” was a prolific writer as well as a WWII Marine Corps officer, historian, competitive shooter, adventurer, overseas security contractor, and founder of the American Pistol Institute (API) on his ranch, more popularly known as Gunsite. When Weaver beat Cooper (and nearly everybody else) 3 years in a row in the Leatherslap matches, Cooper studied what Weaver was doing. Cooper adopted the isometric tension Weaver got from the bent elbow stance into what Cooper eventually called his “Modern Technique of the Pistol,” a formalized system, the pistol equivalent of a martial art.

The Modern Technique differed from other systems, such as Ayoob’s StressFire, as Karate differs from Jiu Jitsu. Which particular systems you choose are not nearly as important as how much you practice them.

Chapman’s straight arm appealed to Cooper, who like most Marines was first and foremost a rifleman, as it essentially converted the gun arm into the stock of a rifle; the support arm pulls this “stock” back into the gun side shoulder. The Modern Technique stresses the isometric tension not between hands or arms but between the support hand and the gun-side shoulder. As taught by API, the gun arm elbow should not be bent much, if at all. In other words, the “Weaver” used by adherents of the Modern Technique is in reality a Chapman (Modified Weaver).

Standing Tall–or Not

Jeff Cooper taught Chapman’s version of Weaver as a “dignified,” standing tall, erect stance. According to Gregory Boyce Morrison’s The Modern Technique of the Pistol, which was edited by Cooper and lays out the essentials of Cooper’s system,

“The legs should appear straight to a bystander, but the knees should be unlocked. . . The back is straight; one leans neither backward nor forward. The head is erect.” (Morrison, pp. 69 – 70)

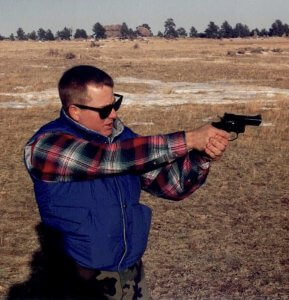

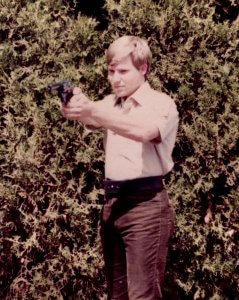

This is what Modern Technique Weaver looks like, under ideal range conditions:

This is what that ends up looking like when somebody is trying to hit you with a rubber crowbar (note the cat-like crouch):

Vis (Power)

One of the tenets of Cooper’s Modern Technique was that all handguns are underpowered, so one should carry the most powerful handgun one can master. For many, and certainly for Cooper, that was the Government Model (M1911 type) pistol chambered in .45 ACP. The bent elbow isometric tension of the Weaver stance gave even a 98 pound female enough leverage to control a GI .45 in multiple rapid follow on shots (that’s not hyperbole; I’ve seen it).

Cooper was hugely influential in the shooting world, and the pistol world in particular. Along with Chapman, he was one of the founders of the IPSC action pistol sport. Cooper felt that unfettered competition was one way to find out what works and what won’t. He later felt that IPSC (and its American branch, USPSA) had drifted too far from its intended purpose–finding out what might work best in a gunfight–and become too much of a gear game (indeed, too much of a game in general). IDPA, the International Defensive Pistol Association, was eventually formed to bring competitions closer back to their defensive roots.

In 1994, my mentor Max M and I spent a few hours in Cooper’s home speaking with him, and drinking his gracious wife Janelle’s tea. Like many in his generation, Cooper had no respect for people who didn’t tell the truth as they saw it, regardless of who it offended. Also, like most Western warriors of the 20th century, Cooper understood and fought against the very real evils of communism. He was willing to tolerate what he viewed as lesser evils (for example, right wing dictators and apartheid) in order to combat it. Although he was a brilliant, principled man, Cooper believed that going to “one man, one vote” too soon in Rhodesia and South Africa would inevitably lead to anarchy and communist takeover. He had the temerity to proclaim that politically incorrect belief publicly. This alienated him from many of his followers and made his writings less popular as time went along, but it should not blind us to his many positive contributions to the art of defensive pistolcraft.

Two Hands

Even Sykes, Applegate, Fairbairn, and other early- to mid-20th century advocates of crouched point shooting were OK with using two hands and sighted fire at distance–on those rare occasions when pistols are used at any significant distance. But Cooper was one of the first, and most influential, to advocate using two hands with hand guns as a default. His influence was so successful that now, we as instructors often have a hard time helping students to shoot handguns with one hand.

API

Cooper wrote many, many books and magazine articles. The American Pistol Institute on his Gunsite ranch was the other reason he had so much influence. There were a few other civilian run shooting schools in the 1970s and ’80s, but API (now known as Gunsite Academy) was the gold standard, and one of the few non-government range facilities in the US that had, for example, an indoor shoot house.

Many of the big names in firearms instruction were at one time Gunsite instructors. Military special forces and law enforcement firearms instructors from around the world trained at Gunsite, and still do. They took API’s influence with them when they taught for their own agencies.

1980s: Modern Technique Becomes Widely Accepted Doctrine–and Bladed

The FBI officially adopted Cooper’s Modern Technique in 1982. Although Cooper taught that the feet should be nearly equidistant from the threat, as with an Isosceles (API 250, General Pistol Course, Student Notebook, 1988 edition, p. 7), the FBI, and the other law enforcement agencies that also adopted it, saw that the Weaver’s bent support elbow lent itself to the bladed position taught in police academies as the “field interview stance,” which among other things was intended to keep one’s holster side away from suspects. Weaver was thus modified again and taught that way, very bladed, when the USAF adopted their version of the Modern Technique as official doctrine (at the same time we transitioned to the M9 pistol) in 1988.

Boxer’s Stance (re-) Modifications

A war or two later, when we (re-) discovered that people in fights tend to lower their center of gravity, pull their shoulders up to protect their necks, turtle their heads, and square their hips toward perceived threats with a wide stance in case lateral mobility is suddenly needed, often with a “drive” leg back to keep from getting bowled over onto our backs, we began speaking of a (re-) Modified Weaver which kept the Weaver’s bent support elbow HOLD, but adopted more of a “boxer’s,” hips-squared-to-the-threat STANCE.

Ironically, that’s not too different from how Jack Weaver actually stood, at least in the photos I’ve seen.

I was called up by the Army ‘Guard in 2003, and assigned to the Davis Monthan AFB firing range as a small arms instructor. I taught that (squared off boxer’s stance) Modified Weaver to troops deploying to Iraq and Afghanistan, in contravention of USAF bladed Weaver doctrine. At first, I was met with some pushback, but shortly thereafter USAF Security Forces Center, reacting to input from various sources, began encouraging a “modified” (squared off) Weaver as quasi-official doctrine.

This was because Weaver, especially in its very bladed bastardization, had some downsides. One was that it turned the weaker portion of the issued Interceptor vest, the open armpit, toward the enemy, while angling the rifle plates away.

Another was, if you start out with your support side toward the enemy (bladed), like your feet are on a skateboard, it’s hard to traverse even farther toward that side when his friend flanks you.

More importantly for you, unless you wear body armor, the bent support elbow made Weaver a 3-dimensional, 4 sided shape, rather than a more stable 2 dimensional triangle. Moving the support elbow around in Weaver moves the gun all around. A common error with Weaver is keeping the support elbow OUT, rather than DOWN; elbow down reduces windage errors and improves recoil control. One exception might be if your eyes and hands are cross-dominant. If slightly out (rather than down) the support elbow can pull the pistol across your face to a position in front of your dominant eye.

Diligentia (Accuracy)

Because of all these multiple variables, Weaver practically demands sighted fire. Jack Weaver’s use of the sights differentiated him from his fellow Leatherslap competitors more than his hold did.

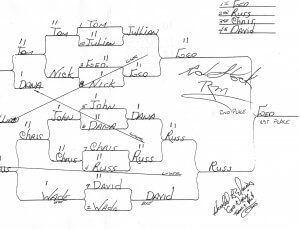

Hundreds tried out for the chance to be in the Leatherslap shoot-off, by putting one shot on a 12″ steel plate at 21 feet, 5 times in a row, from the holster each time (this was more than a decade before Dennis Tueller’s “How Close is Too Close?” tests resulted in the so-called 21 foot “rule” for contact weapon vs. gun). The 16 fastest Leatherslappers then got to shoot off against each other, two men at a time, against a series of balloons, in a single elimination, bracketed shoot-off. There was a lot of “match pressure” in the shoot-off, because not only did you have to be faster and more accurate than the man beside you, you could hear his shots and see his balloons popping in your peripheral vision.

The balloons were also at 21 feet, except in 1963, when 3-time champion Elden Carl convinced Jeff Cooper to move them to 15 feet. Carl was inspired to request the change after he read a LAPD study that found 80% of their law enforcement shootings were within 12 feet of the assailant (“Recollections of a Combat Master,” EldenCarl.com). After that year, the targets went back to 21 feet and stayed there.

Leatherslap differed from other quick draw competitions of the 1950s which inevitably used single action revolvers from old-west style rigs to bust balloons with blanks. The use of blanks necessitated close range to pop the balloons. Cooper’s Leatherslap used live ammo, permitting more distant targets. Any type of handgun (including DA revolvers and semi-auto pistols) was permitted. Increasing the range to 7 – 10 yards separated the men from the boys, but it also artificially created a need for sighted fire.

In 1994, I won the API 250 shoot-off at Gunsite against faster, more skilled shooters with better guns. I had a wartime production M1911A1 with tiny stock sights. Each shooter had to shoot his or her own array (falling steel plates had replaced the balloons of Leatherslap), faster than the opponent shot his. The plates themselves were farther away than assailants in “typical” gunfights (if I recall correctly, one of them was back by the berm), but they were not so much distant as small, about 6 inches in diameter. Like firing head shots on multiple opponents. The bigger, easier to acquire “combat” sights on my competitor’s guns did not work as well against the small, distant steel targets as the tiny sights on my old war horse, so I edged them out–not by shooting faster, but by shooting more accurately.

In other words, four decades after he founded Leatherslap, Cooper’s school was still using targets so small / far away that sighted fire was imperative. Shooting (and watching others) shoot at difficult to hit targets forced Cooper to arrive at the conclusion that sighted fire is necessary, and as if to prove it, small, distant targets were always part of his programs.

Although Cooper gave lip service to muscle memory and shooting in the dark, he taught that his Modern Technique should always be practiced, dry or live, using the sights, with a “flash sight picture” focused on the front sight. He said the sights should be used whenever possible, especially in a fight. Which is not a bad idea, if the bad guy is far enough away that you can safely bring the pistol up between your eyes and him.

MORE THAN HALF THE TIME, HE WILL NOT BE.

That big guy with the machete will probably draw your attention away from that 1/8″ front sight you probably won’t even be able to see in the dim parking garage after hours, anyway (Chiodo, Winning a High-Speed, Close-Distance Gunfight, pp. 56 – 62).

Isosceles Makes a Comeback

Before many agencies got around to adopting the Weaver, successful IPSC competitors were already going back to Isosceles based holds. They endlessly debate the merits of this grip or that grip (some competitors create isometric tension by pressing in from the sides, some press fore and aft, some say 80% of your squeezing should be done with the support hand, etc.) but regardless of the nuances, variations of the Isosceles have dominated IPSC for decades. Isosceles has fewer variables than Weaver, which for most people makes it faster.

The Border Patrol has one of the most deeply ingrained “shooting cultures” of any federal agency I have worked for and / or with (the list is long, but distinguished). When I went through the BP Academy in 1996, they were teaching Isosceles.

To get the “school solution” foot position, the BP Academy instructors had us place the ball of our gun side foot in the instep of our support side foot, then move one foot or the other till they were about shoulder width apart. This placed the support side foot about 4 inches father forward than the gun side foot. Which worked, because even with a locked arm Isosceles, the support hand wraps around the front of the gun hand.

Since the 1990s, Weaver has fallen out of favor in many professional circles, except for die hard Modern Technique fans (like instructors at Gunsite and Front Sight). Sergeant Major (SGM) Kyle E. Lamb, who has forgotten more about killing men with guns and knives and laser guided bombs than I will ever learn, hates Weaver:

“It’s asinine that we even have this discussion, but there are still a few enclaves holding on to the Weaver stance. . . The Isosceles shooting stance was used in WWII by the . . . Founding Fathers of United States Special Forces, yet we have to endure discussion about a stance that was developed to shoot balloons. Enough said.”

—Stay in the Fight!! [a] Warriors Guide to the Combat Pistol, pp. 14 – 15

SGM Lamb uses an old photo of operators training in Isosceles to corroborate this statement. Based on the training manuals I’ve seen, and books I’ve read, and WWII vets (including an actual OSS operator) I’ve spoken with, MOST of the training for just about every allied soldier, sailor, airman, marine, or spy armed with a pistol in WWII was one handed from a crouch, but on those rare occasions when they did train to shoot two handed (if at all) it was prone or in some version of Isosceles, as Weaver would not become well known for another two decades.

SGM Lamb is clearly a subject matter expert, who has killed more than his share of our nation’s enemies, but his justification for Isosceles over Weaver lacks a logical foundation. Lamb’s statement is like saying “If it was good enough for Robert the Bruce, who was a helluva man back in the 13th & 14th centuries, it’s good enough for me!” And whether LA County Sheriff’s Deputy Jack Weaver practiced on balloons or cardboard or steel, you can bet he was deadly serious about being able to shoot the very real, flesh and blood felons he was tasked with apprehending on a daily basis. The men who won Leatherslap before and after Weaver were also police officers.

Celeritas (Speed)

Indeed, although Lamb makes it sound like some sort of parlor trick, shooting at balloons while a man beside you is trying his best to shoot all of his balloons before you can finish yours was the 1950s equivalent of Force-on-Force. They didn’t have Simunitions FX marking cartridges back then.

Most of the men SGM Lamb trained and fought with, half a century after Deputy Weaver worked the mean streets of Lancaster California, were themselves Alpha males among Alphas who could bench press Volkswagens. What works for them may or may not work for you.

SGM Lamb prefers both of his gigantic, protein-enhanced arms to be slightly bent like shock absorbers in his personal version of Isosceles, as one of our students is doing here:

Ironically, that’s almost EXACTLY how Jack Weaver shot–with both elbows bent. One of Weaver’s was just bent a little more.

This photo of Jack Weaver competing in a shoot-off against the guy in the hat is perhaps a bit misleading (just like the media misleads by only showing you part of the video). The Leatherslaps started (as the name implied) in the holster, and in this snapshot Weaver does not appear to be quite at the end of his presentation (draw stroke). Weaver was one of the few Leatherslap competitors before 1965 to bring the gun up as far as his sight line, and in this photo, he’s not quite there.

His opponent, like most, fired from a one handed, bent elbow, below line of sight hold, which made him faster but not necessarily the first to get effective hits. Remember, in order to make the game challenging, the Leatherslap targets were at least 21 feet away (except in 1963). Weaver’s two handed fire with a flash sight picture made him slower but more likely to get effective hits at that distance.

While it may be argued that “only the hits count,” and gunbattles do sometimes occur at extended ranges (I can tell you that from personal experience), the vast majority of lethal encounters occur at 9 feet or less.

Legs and Feet

Lamb keeps his front knee bent over his front foot. This is nothing new. Tom McLinn, a USAF M9 champion who represented Space Command at Peacekeeper Challenge (AF wide cop competition) in the mid 1990s, stood in an Isosceles with a slight bend at the elbows, slight bend at the waist, slightly wider feet, and bent knees. When he stood in one place. In McLinn’s own words, “my forte that earned me top gun was ‘moving and shooting’.” Incidentally, McLinn says that he has since moved on to a more locked out Isosceles arm position, and believes that has made him a better shooter. It works that way for him.

There are two lessons here. First, good guys have shot many, many bad guys from Weaver, Isosceles, StressFire Turret, FBI Crouch, CAR, and Applegate-Fairbairn holds. It doesn’t matter what system you use. What matters is how good you are at it.

I have studied Israeli Krav Maga and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, and dabbled in other martial arts like Russian Systema. If Lee Jun-fan (Bruce Lee) were alive today, even at 80 years old, I have no doubt that he could still beat me to a pulp. That’s not necessarily because Lee’s art, Jeet Kune Do, is better than Krav or BJJ, but rather because Bruce was so much better at his arts than I am with mine.

The second lesson is, what works best in one situation may fight you in different situations. You should have more than one tool in your tool box.

For my own part, I still primarily shoot “modified” Weaver, because I grew up in the Modern Technique and it would take me 20 – 30 years to un-learn it. But I don’t use Weaver exclusively. Here’s why.

All this talk of “stance” is 2-dimensional, square flat range thinking. As Joel of Warlizard Tactical points out, it assumes that the bad guy will always be in front of you, like the targets are on the firing line, that he will stand in one place, like the targets do on the firing line, and that you will always be standing in one place (or at best, sprinting between static firing positions), like you usually do on the firing line. Said it before, and we’ll say it again: if you are standing in one place, you may very well be sucking up incoming bullets.

Jim Cirillo, who would know (he survived at least 17 gun battles), said that in a flash fight, getting your gun out is not your first priority. If you move FAST, perpendicular to the incoming fire, it’s much harder to hit you.

WHAT IF THE THREATS AREN’T IN FRONT OF YOU?

As Michael of Warlizard Tactical points out, Weaver fights you if the bad guy is off to your gun side. Weaver can actually help pull your gun arm toward the support side if the bad guy is to that angle (to 9 o’clock, for a right handed shooter)–that is, if your version of Weaver didn’t already start in a bladed stance. If you’re bladed, you’re already shooting toward your support side by default, and shooting farther toward your support side would be problematic.

Below, Instructor Greg G moves to stack his cardboard opponents, pivoting to engage the targets on his left after hosing the closer target (if you want to know why, take one of our Managing Multiple Assailants classes). A Weaver hold helps pull his gun hand toward that side.

Isosceles is more stable in both directions through a limited range of motion, say 10 o’clock to 2. This works great for IPSC / USPSA competitors, who often traverse but get penalized if they come close to the “180 degree safety plane.” Isosceles will certainly take you farther toward your gun side than Weaver.

Mas Ayoob, in his StressFire system (adopted lock, stock, and stance by the US Army about the time the Air Force was adopting Weaver; see FM 23-35, Combat Training with Pistols and Revolvers, dated Oct 1988), compared Isosceles to a tank turret. His “Turret” stance had Isosceles arms, hips squared to the target, and a drive leg back like Pablo of WLTac prefers.

Even Isosceles has limits traversing to either side. Beyond that range of motion to the gun side, say to 5 or even 4 o’clock for a right handed shooter, NO TWO HANDED HOLD WILL SERVE YOU. ONE HANDED IS SIMPLY THE WAY TO GO after that point.

Counterclockwise from the top, beyond 9 o’clock or so (again, for a right handed shooter), even Weaver isn’t enough. If you’ve been driven off the road, your engine is wrapped around a palm tree, your feet are pinned under the dash, and a Sinaloa Cartel member is approaching from your 7 o’clock (in what, I’m sure, would be a case of mistaken identity), your only salvation will be an even more bladed hold, e.g., Paul Castle’s Center Axis Relock (aka CAR).

CENTER AXIS RELOCK (CAR)

British Detective Paul Castle taught CAR as a complete system, to the exclusion of other methods. It brings the gun in tight to the user, which is often useful for retention in double-decker busses, “tubes,” and other crowded European settings.

Heloderm teaches CAR as a niche technique for angles past 90 degrees to the support side.

Like a Weaver on steroids, CAR is VERY bladed, and uses isometric, fore-aft tension to control recoil. This is especially important, because in some CAR holds, the pistol is mere inches from your nose, as the slide reciprocates.

CAR uses different holds, starting with “CAR High” (which is not high) across your chest (shooting past your support side elbow) for retention, and moving upward and onward from there, not toward Churchill’s “broad sunlit uplands,” but rather toward “CAR Apogee,” something resembling a very bladed Weaver, for longer range shots. “Combat High” is a search technique, conceptually the equivalent of the Modern Technique’s “Guard” position.

CAR High

CAR Extended

CAR Apogee

Re-locked GRIP

The main thing that differentiates CAR from Weaver is GRIP. The support hand palm, rather than the fingers, are in front of the gun hand fingers, pulling back. What you do with your support hand fingers and thumb is not really that important (I didn’t get a chance to meet him in person, but before he died, I sent Castle an email asking what to do with your thumb and fingers, and he replied that it didn’t matter; the tension of the palm is what controls the muzzle flip).

It IS important in CAR to keep your gun arm wrist locked. This makes the pistol roll slightly inboard in CAR Combat High, Extended, and even Apogee. This enabled Castle, who had problems with double vision, to aim through the sights using only the eye on the side the pistol was on; his nose blocked the other eye from seeing the sights. When you are shooting at close range threats chasing you across a parking lot, you can actually sight down the top corner of the slide, rather than through the sights (course notes, Fight Focused Concepts Point Shooting Progressions and Force-on-Force Gunfighting, 31 Jul – 01 Aug 2010).

There are other aspects of the CAR system. For example, Castle recommended always firing 4 shots, then re-assessing the situation (Castle used high capacity 9mm GP-35 pistols; compare that to Cooper’s Modern Technique, which recommends 2 shots from the 7+1 shot .45 Government Model carried by “real men,” before assessing if a head shot is necessary). However, many of those aspects are not germane to this discussion of Grip, Hold, and Stance.

ONE HANDED PISTOL HOLDS

These days, we tend to see one handed shooting as an emergent compromise. Maybe you are holding a flashlight or a baby in the other hand.

Maybe your other hand is wounded, like Deputy Jennifer Fulford’s was. But for most of their existence, pistoleros didn’t need those excuses. The handgun was intended to be shot one handed.

Until the 1960s, the handgun was just that: a hand gun, not a handS gun. Gunfighters in the Old West almost always fired it with one hand. They used bent elbow fire when they shot under a Faro table, and in other close quarters situations.

Until Jack Weaver won in 1959, and for 6 years after his historic ’59 win, the Leatherslap champions all shot one handed. El Cajon Police Officer Elden Carl, who defeated Weaver in 1960, ’61, and ’62, believed that if the Leatherslap shoot-off had moved to a more “street likely” 15 yards or less, one handed point shooting would still be a predominant pistol method trained today.

My biggest disappointment with the 1963 Leatherslap was that the 15 foot man against man shoot-offs were not made permanent. If they had continued, perhaps one-handed point shooting would have survived, resulting in more options for the shooter, and in [the] case of police officers possibly fewer suspects dying by mistake. The reason I say this is because while using a two-handed pistol hold, it is difficult to see effectively when you are looking at your forearms, wrists, clasped hands, pistol and sights. It also is more difficult to run fast and be able to point in multiple directions if necessary.

–Elden Carl, “The Big Bear Leatherslap’s Finest Hour,” TopGunMotorcycles.com

Fairbairn, Sykes, and Applegate

In the first half of the 20th century, two men who supervised the Shanghai police made a study of pistol craft–having, as they did, ample opportunities to examine gun battles. Shanghai was a rough town, and many of the criminal element were practiced in the martial arts of their various nationalities.

W.E. (for William Ewart) Fairbairn was the NCOIC of Musketry for the Shanghai Municipal Police. Eric Anthony Sykes was a Remington rep who joined the SMP and eventually ran the SMP Sniper’s Unit. Sykes and Fairbairn determined, among other things, that when startled or in a state of heightened anxiety, people crouch like cats.

Like many great discoveries, this tendency to lower the center of gravity in anticipation of trouble was found by accident. Reviewing the scene of a nighttime gun battle the following day, they observed a clothes line across an alley their officers had moved through. It was at about face height for most of their multi-national officers, yet none of them had noticed it the night before, in the dark. That’s because the cops had instinctively crouched as they went through.

Sykes and Fairbairn combined a crouch with bent arm shooting at contact range (roughly, inside of two arms’ length), for retention. This was later adopted by the FBI and given their three letter name: the “FBI Crouch.” Legendary Oklahoma lawman and FBI Special Agent Delf “Jelly” Bryce survived at least 19 gun battles; photos show him using the FBI crouch.

Sykes and Fairbairn combined a crouch with bent arm shooting at contact range (roughly, inside of two arms’ length), for retention. This was later adopted by the FBI and given their three letter name: the “FBI Crouch.” Legendary Oklahoma lawman and FBI Special Agent Delf “Jelly” Bryce survived at least 19 gun battles; photos show him using the FBI crouch.

My initial USAF handgun training still retained some elements of the FBI Crouch. When I attended more advanced, Weaver based, civilian schools, my instructors poo-pooed bent elbow fire and bent knees as an inaccurate and outdated throwback to less enlightened times. But that’s because almost all of our training in the 1980s emphasized marksmanship, the ability to hit with small groups at distance, as the be-all and end-all of firearms skill.

What most of us didn’t realize at the time, although it was even true back then, is that 54% of all police officers killed are within two-arms’ reach of their assailants (see the Distance versus Death graph on pages 41 – 44 of Chiodo’s Winning a High-speed, Close-distance Gunfight). Heloderm Instructor Ken S fired from a bent elbow hold in something not unlike an FBI Crouch–with a knife through his support hand–when he shot a man who was trying to kill him in Ft Worth, Texas.

Fairbairn and Sykes combined a crouch with a locked arm held downward at about a 45 degree angle while searching (their equivalent of Weaver “Guard” and CAR Combat High).

When a target was found outside of close contact range, the straight locked arm was brought to the line between the shooter’s face and the target, and fired almost as soon as it got there. Both eyes were open, focused on the threat (note the blue painter’s tape over the sights in these photos).

The support hand was out, which looks goofy when one is standing but happens naturally, kinesthetically, as a counterbalance when one is jinking back and forth to avoid being shot.

Initially, Sykes and Fairbairn taught that the pistol should be held along the body’s centerline, with the gun hand wrist bent back slightly to point the gun at the target. In it’s more refined versions, their method has the grip in line with the forearm. The pistol is held straight up and down, not canted (as it is in slow fire bullseye shooting) so that the long axis of the target–a standing man–coincides with the bounce of the pistol. Use a convulsive “death grip,” rather than the “firm handshake” grip taught in marksmanship based schools, because it controls recoil more effectively in one handed shooting.

While this method is not accurate enough to consistently hit A-zones or pull off head shots at 25 meters in an IPSC match, it is accurate enough to put rounds in a man at the ranges where most pistol fights take place, and lightning fast. It was simple enough be taught to German speaking school teachers and plumbers recruited as spies and about to be dropped behind enemy lines, in a matter of hours.

Sykes and Fairbairn taught these methods to allied forces, particularly commandos, spies, and saboteurs, in WWII. American Rex Applegate went through their training and taught those methods to US forces. They shot prone at 30 yards. At 20 yards they used the “long range standing position” (essentially an Isosceles). Most of the time they shot closer and used what they called “orthodox” one armed, crouched holds.

Their story, and those of the brave men and women they trained, is fascinating. The best and most thorough examination I’ve seen of the development of modern pistolcraft, and the Sykes Fairbairn methods in particular, is William L. Cassidy’s Quick or Dead. A more concise examination can be found in Col Rex Applegate’s and Michael D. Janich’s Bullseyes Don’t Shoot Back. Lou Chiodo, a world-class trainer who convinced his agency, the California Highway Patrol, to adopt Sykes Fairbairn point shooting methods, outlines them in Winning a High-speed, Close-distance Gunfight.

Chiodo told me that while their accuracy did not improve, officer survival (and conversely, wounded / stopped bad guys) went up when CHP adopted those methods. They traded precision for adequate accuracy (read that “more effective return fire”), far faster. In Chiodo’s version, the support arm comes up to protect the head as a default.

One Handed Training Options

Heloderm teaches one handed shooting in several contexts:

- As part of Night Fighting classes, when using hand held flashlights.

- As part of Compromised Positions courses, as a response to being wounded in one or the other arm.

- In Running and Gunning classes, to engage threats at extreme ranges of motion to the non-gun side. One handed shooting is acually MORE accurate (or less inaccurate), when running at a full sprint, than two handed fire.

- We plan a dedicated Point Shooting class, where we will cover Sykes Fairbairn methods and other target focused shooting, in the first half of 2021.

So, young grasshopper, which grip / hold / stance is best? That’s exactly right: “It depends . . ..”

–George H, Lead Instructor, Heloderm LLC