Worm was right there with us

Was it bitter then, with our backs against the wall?

Were we better men than we’d ever been before? . . .

And we were smaller then, you see, but soon we gathered like a storm

They don’t understand what that thunder meant at all

–Kris Kristofferson, “Living Legend”

“Worm” was a bedouin.

He looked like a bedouin–almost a Hollywood stereotype of a bedouin.

His face was narrow and pointed with a huge, hooked, hawk nose. But it was his unctuous, ingratiating manner, more than his looks, which caused T-bone to nickname him “Worm.”

I can’t for the life of me remember his real name. Faris, a Saudi warrant officer and our liaison to the King’s Amn (security) forces, had introduced him to us.

Worm worked in our sector, which is to say we worked in his. The area, which we called Echo 14, was the northwestern most on the civilian side of King Khalid International Airport. KKIA was north of Riyadh, in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

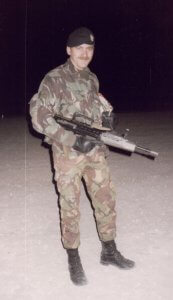

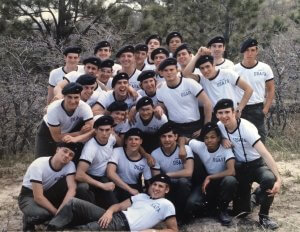

“We” were Fire Team Alpha, Third Squad, of Alpha Flight, 1703 Ground Defense Force (provisional), assigned to the 1703 Aerial Refueling Wing (provisional).

The 1703 AREFW(p) was made up mostly of KC-135 tankers, both A and R models, from various Strategic Air Command (SAC) bases in the US.

We also had EC-135s and AWACS, all based on the Boeing 707 airframe.

We were there, initially, to keep the Iraqis from driving further south into the oil fields of our ally Saudi Arabia. The Pentagon planners called that operation Desert Shield. Later, when we had enough personnel and materiel on hand, Coalition forces kicked the Iraqi squatters out of Kuwait (Op Desert Storm).

We had arrived from cool Wyoming the previous August (of 1990), when the temperatures on the Riyadh flightline were in the upper 120s. I distinctly remember standing 2 or 3 feet away from Sgt Lyle Finch, who’d just come in from the flightline, by the armory window. I could feel the heat radiating off of Lyle, his M60, and his equipment.

Throughout Operation Desert Shield, we had been confined to the King’s side of the airport. He had his own, quite magnificent Royal Terminal, which he was gracious enough to let us use. More importantly, King Fahd had his own runway and parallel taxiway, which our tankers parked on to stay out of the way of the busy civilian side of KKIA.

During Desert Shield, we worked six 12-hour shifts a week. It was actually about 14- or 15-hours, by the time we armed up, held Guard Mount (daily roll call and briefing), convoyed over to the airport, relieved the off going posts and patrols, and later did that in reverse, getting relieved and turning in our weapons at the end of our shift.

Our fire team’s (and much of Alpha flight’s) work days started midnight to noon, but if memory serves that eventually changed to dusk to dawn (I may be mixing up my deployments after all these years). I remember working at night most of the time. The cooler temperatures were nice, especially at first (the Arabian desert got bitterly cold at night that winter).

More importantly, if there were going to be any attempts at infiltration, they would probably be at night. That had been our flight sergeant’s experience during the previous war. Master Sergeant (MSgt, E-7) Mark Galpin, a red faced, red haired bear of a man, had been a young airman in the Security Police at Bien Hoa and Cam Ranh Bay in Viet Nam.

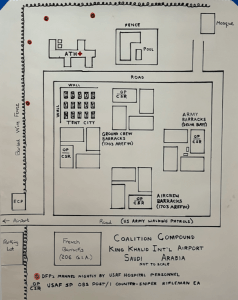

Before the war, we also rotated between various posts, and didn’t always work together as a fire team. Some of my personal favorite duties were rooftop marksman in the 1703 cantonment compound (where the chow hall and most of the enlisted quarters were; see Appendix III), and Ambassador 1, in the Saudi Amn command post, which monitored their state-of the art cameras.

Ambassador 1

Security cameras are commonplace today but back then, closed circuit TVs mated to traversable cameras which could zoom in were quite remarkable. The Saudis had more money than they knew what to do with, so everything they bought–including their security system–was first class.

Ambassador 1 also had the advantage, early on, of being one of our few air conditioned posts. The US Central Security Command post (CSC, known today as a Base Defense Operations Center, or BDOC) for KKIA was in a trailer with a window AC unit, but Ambassador 1 was in the Royal Terminal. The bathrooms were marble with gold fixtures.

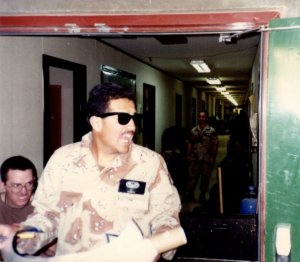

Ambassador 1 was really a job for a Tech Sergeant (TSgt, E-6) or above, and I was only a Staff Sergeant (SSgt, E-5), but I got assigned to it because most guys hated working there. The language barrier was the main reason; racism might also have played a part. I had made some small effort to learn Arabic and tried to think of our hosts as different rather than weird, so I got assigned to Ambassador 1 fairly frequently.

The call sign was just Ambassador initially, but later we also added a liaison to the British, so the Saudi liaison job became Ambassador 1.

As anyone who’s ever been in a language immersion program can tell you, it strains your brain a lot, especially at first. But some of my counterparts enjoyed practicing their English, and I learned the answers to several mysteries a young man wondered about, concerning life in the Kingdom.

For example, “Do you guys really practice polygamy?” and “How does that work?”

Most men, they said, couldn’t afford more than one wife. I wondered how that was possible, in such a wealthy land, but now that I’ve been married for three decades I realize they weren’t talking about money. I can barely keep one woman happy.

Only princes could afford as many as four. I was sternly admonished that one should either have one or three wives–but NEVER two. With three, they said, there were always shifting alliances among the spouses, and a healthy balance of power. A man with two wives was always caught in the crossfire of any family disagreements, would never know any peace.

We did not get into any details about what went on behind closed doors or how that worked. They did admire the photo of my girlfriend (now my wife) I kept in the nametag window of my gas mask pouch.

One other perk of working Ambassador, that I had nearly forgotten till I was speaking with 1703 GDF vet Jeff Jones, was the meals.

Instead of box nasties (in-flight meals) or MREs (“Meals that would even be Rejected by starving Ethiopians”), the TCNs (Third Country Nationals, Sri Lankans, Pakis, or other “Hodgies” imported by the Saudis to do their grunt work) would bring a 6×4 foot tray into the Amn Security Control Center and set it on the floor. The silver platter (wouldn’t be surprised if it was actually silver) was completely covered with rice. Set around inside it were various delicacies, often including chicken or dove.

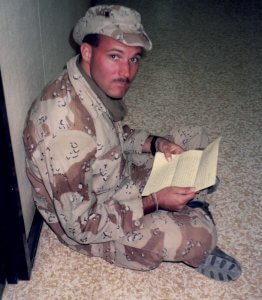

We would sit cross-legged on the floor around the platter, reaching in to grab something, and drinking chai (sugar with a few drops of strong tea in it).

Transitioning to the other side of KKIA

The civilian side had 4 triangle shaped terminals, with numerous gates. The gates, importantly, each had access to underground tanks full of jet fuel. Hydrocarbons were the one thing that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia had in abundance (not takin’ anything from Stormin’ Norman, but Patton and his Third Army could have driven the Nazis all the way to the Urals with that much free gas on hand).

So when the air war (Desert Storm) kicked off, we gave Saudia, the Saudi Arabian national airline, just enough time to push all their aircraft back from the boarding gates before taking over their side of the airport and setting up shop.

Our tankers pulled in, refueled, and pushed back, all day and all night, every day and night.

The previous November, the United Nations had passed UN Resolution 678, giving the Iraqi squatters till 15 Jan 1991 to pull all their troops out of Kuwait. Saddam kept his troops in place up to the deadline and after it.

On the evening of 16 January, we waited outside the CSC while the leadership briefed within. MSgt Galpin came out after the meeting broke up and announced, “This is it, men. We’re going to war.” It was something I’d always expected to hear at some point in my career, but it was still surreal.

Funny, I seemed to remember he’d always referred to us as “boys” before that.

When the war started in the wee hours of 17 January 1991, we kept the same schedule, but went to 7 days a week for several weeks. We had also stopped rotating posts, for the most part, and worked together with the same guys on the fire team and in the same sector. No more Ambassador 1 for me.

For the next few months, the duration of Desert Storm, Fire Team Alpha’s call signs were

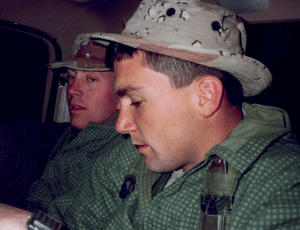

- E-14 (“Echo Fourteen”): Me, the fire team leader, armed with an M16 and my limited wits

- E-14A (“Echo Fourteen Alpha”): Sergeant (Sgt, E-4) Robert C. “Chris” Williams, aka “Jethro,” armed with an M203 grenade launcher mounted to his M16

- E-14B (“Echo Fourteen Bravo”): Sgt David A. “T-bone” Tenorio, armed with an M60 general purpose machine gun and an M9 pistol

- E-14C (“Echo Fourteen Charlie”): Airman First Class (A1C, E-3) Jason T. “Jase” Bilyeu, our assistant machine gunner and driver, armed with an M16

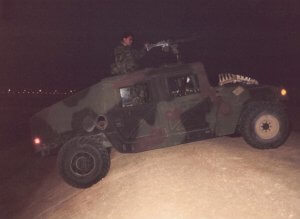

All four of us blundered into Worm’s patrol area in a Humvee (High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle, HMMWV).

Worm drove a Suzuki Samurai, or something very similar to it. He was always solo, although a Saudi warrant officer would sometimes come around for their equivalent of leader’s post checks.

One of their warrants spoke English well, and early on I asked him about Worm’s beard.

“Your men will have to shave those off,” I said, “if their gas masks are to do them any good.” They had facemasks, the most important part of chemical agent defense, although as far as I could tell they did not have complete chemical ensembles, the charcoal impregnated suits we wore.

The warrant patiently explained that the men wore their beards to honor Allah.

“Yes, but surely God would not want them to die horrid deaths,” I countered. Saddam had gassed his neighbors the Iranians and his own people with Tabun and Mustard and probably also Sarin. We were fairly certain that when the SCUDs began falling, they could be bringing chemicals with them.

The warrant even more patiently explained that they would rather die horrid deaths than to offend Allah by removing their beards. I learned to admire both the courage and the faith of our Amn counterparts. Indeed, the two are inexorably intertwined.

“Fear is having no faith.”

–Ken Good, quoted in Tiger McKee’s The Book of Two Guns, p. 47

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was concerned enough about Saddam’s WMDs (weapons of mass destruction, including chemical agents) to issue a promise few doubted “the Iron Lady” had the resolve to keep: If any WMDs were used on British coalition troops, she would not hesitate to nuke Bagdad. She left office on 28 Nov 1990, a month and a half before the war began, but thankfully, Saddam didn’t end up challenging her successor John Major’s resolve, or George H.W. Bush’s, by using his WMDs on us.

I’m also grateful for the considerable restraint exercised by the Israelis, even after Saddam launched SCUDs on Israel. By trying to goad Israel into the conflict, Hussein was trying to drive a wedge between us and our Arab coalition allies. It didn’t work. One of my high school classmates, Nancy Ben-Asher, was in Tel Aviv while the SCUDs were dropping. Unlike us, she hadn’t signed up for that.

We patrolled randomly around sector Echo 14, which was not too large for foot patrol but large enough that being away from our rig might find us quite literally flat footed and unable to respond quickly to any trouble that came up on the other side of our area. Accordingly, we almost always stayed in or near the Hummer.

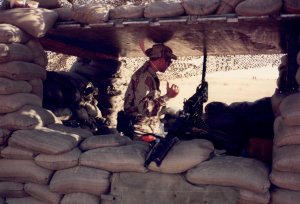

There was a large rectangular hole dug in about the middle of sector E-14. I think it was there to store fuel bladders or perhaps the start of excavation for an underground tank. The Coalition forces at KKIA, which included Aussies, Brits, AnZacs, and French as well as us Americans, were for some reason forbidden from digging into the King’s soil, but that hole was already there.

It was just deep enough that we could park hull down, which afforded some protection for our unarmored Hummer. It would allow T-bone’s hog (M60) in the turret to lay grazing fire in all directions (although we would naturally be circumspect about directing the 7.62x51mm, which had a maximum range of 3725 meters, back south toward our own aircraft).

The rectangular Hole was oversized for a 4-man fighting position–a few vehicles could maneuver around within it–but we could easily defend it on foot. Should it be attacked from the north and then get flanked from the east, for example, we could displace a rifleman or grenadier from one side to another without exposing him to direct fire from either side, because the Hole was deep enough.

It had no overhead cover to protect us from indirect fire, be that mortars from the huge wadi (dry gully or riverbed) that ran north of the airport, or SCUDs from Basra.

The Hole was somewhat steep sided. Our Hummer could easily climb out of it.

But the first time Worm visited us in the Hole, he got his Samurai stuck trying to get out. He got high-centered on the rim. We tried to push him over the top but the best we could do was to push him back in. He tried once more, faster this time, but no joy. Stuck again.

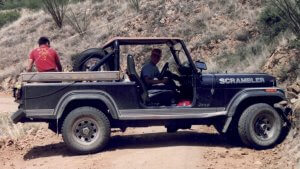

I owned a Jeep Scrambler back in the ‘States, and had actually read the manual for it, which included some four-wheel driving tips.

Through hand and arm signals, I convinced Worm to let me drive his rig out of the hole. I took the bank at about a 45-degree angle. This allowed the chassis to stay high as the front left and right rear tires pivoted over the rim, rather than the middle of the chassis trying to clear the rim with both front tires out of the hole and both rear tires on the bank.

I drove around in a circle, back into the hole, and delivered the Samurai to Worm, as if to say, “Now you try it.”

He did, easily cresting the ridge, and returned again and again, faster and more confidently each time, grinning from ear to ear. After that, we were fast friends, though I only knew about 7 words of Arabic.

About that time, T-bone started calling him Worm. It was alright as a reference between us–it was a mnemonic descriptor–but Dave called him that to his face, or spoke about him using that name when he was there, as if he wasn’t.

I thought it was rude at best, and dangerous at worst. I was certain Worm knew more English than he let on, and although he was only armed with an MP5, those H&K submachine guns were murderous enough at close range.

One thing soldiers do when they meet with allied soldiers is to show each other their weapons. Most of us thought the Saudi MP5s were quite sexy. We had all seen the Christmas movie Die Hard, and I remembered May of 1980 when real SAS commandos had stormed the Iranian embassy at Princes Gate in London with H&K MP5s.

Worm never stopped smiling at us, though. And he was far from the only one on the receiving end of Dave’s rapier wit. T-bone teased everybody to their face, including me.

Because I almost always wore my flak vest and helmet, Dave called me “EEALT”: the “Ever-Elusive American Land Turtle.”

We all called Chris “Jethro,” ’cause he could be dopey at times, like “Jethro Bodine,” the Beverly Hillbilly. Even his mom called him that, Chris claimed.

Sgt Charlie Gibson, with a nose almost as big as Worm’s, was “Snuffleupagus,” after the furry elephant-like character on Sesame Street.

SrA (Senior Airman, E-4) Jeff Parrish, with his gigantic jaw, was known to all as “Chin.”

No person, race, gender, or creed was immune from Dave’s burning wit. He could get away with it, too.

For one thing, T-bone was a combat vet. He’d been on a “boondoggle TDY” (a supposed-to-be laid back, in-the-rear-with-the-gear temporary duty assignment) at Albrook Air Force Station in Panama on 20 Dec 1989, when Operation Just Cause went down. Howard AFB saw little action in that one, but Albrook felt a lot of heat.

Combat vets got cut more slack in the military than those who had not yet “met The Elephant.”

Besides, people still had a sense of humor in the early ’90s. Political correctness was only beginning to reach its pernicious fingers around the throat of our freedoms of speech and thought. Americans could speak their minds in those days much more freely without fear of censure.

In terms of skin color, the US armed forces had for decades been among the most integrated workforces in the world (though it was still almost exclusively a heterosexual male occupation in the early 1990s). We still had (and have) a ways to go, but we reveled in our diversity, instead of trying to hide it, or to blame race for all our problems as many who are fixated on identity politics seem to now.

A Native American of the San Fellipe Pueblo between Santa Fe and Albuquerque (one of his parents was from the Taos Pueblo), T-bone referred to himself as a Red man and an Indian. “As soon as anyone finds out you’re Indian,” Dave later told me with a sense of wonder, “they instantly love you. People are funny.”

Dave told the greatest stories. He spoke of being stationed in Hawaii, and hanging out in hotel bars near the airport. He claimed to have successfully picked up on Australian flight attendants (we still called them “stewardesses” in those days) by convincing them he was Hawaiian and could give them a tour of all the good spots known only to the locals.

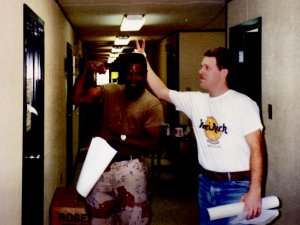

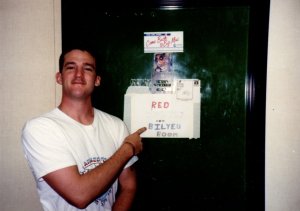

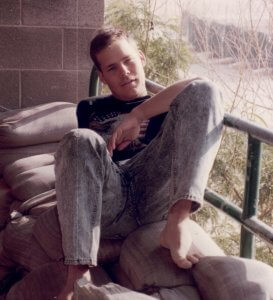

Dave, Chris, and Jase lived in the same room adjacent to mine (I bunked with the other fire team leaders from third squad) and two doors down from the armory (which was adjacent to my room on the other side). Because Jason pronounced his last name, Bilyeu, like the color blue, they put a sign up on the outside of their door:

Speaking of Reds, our first Alarm Reds (incoming fire alerts) had happened the month before the war began.

SCUD launches were first detected when a satellite would pick up the heat bloom of a launch. A few minutes into the SCUD’s ballistic flight, it would be high enough above the horizon to be detected by land-based radars in Turkey and on JSTARS battlespace management aircraft flying over Arabia. Long enough into its parabolic trajectory, it could be painted by sufficient telemetry to guesstimate about where it was going to land.

JSTARS had downlinks to CentCom, Central Command in Riyadh, but some of the older missile launch detection systems (satellites and radars in Turkey that had been initially placed to track launches out of the USSR) sent their information around the world to NORAD, the headquarters of the North American Aerospace Defense command in Cheyenne Mountain outside Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Information about the SCUD launches and subsequent telemetry would be sent up the North American chain of command, over to CentCom in Tampa, Florida, and thence to Riyadh and down our chain to us. By the time a better idea of there the missiles were headed bounced around the world, 8 or 10 minutes had passed.

By that time, the SCUD was about at its destination.

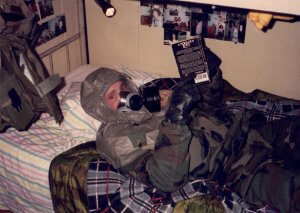

So rather than waiting to see where it was headed, they put us in Alarm Red as soon as a launch was detected. This helped because it took a little bit of time to don our chemical ensembles.

When I had grown up on AF bases, they tested the alarm speakers on Fridays at noon. The siren would spool up, but it would be a steady tone. That was the signal for a peacetime emergency, like a tornado or hurricane.

The signal that we were being attacked was a wailing noise that rose and fell and rose and fell again. I’d never heard an “air raid siren” (except in movies like The Battle of Britain), till Desert Storm. To this day, when I hear a rising and falling alarm noise on TV, the hairs stand up on the back of my head.

On 02 Dec 1990, Saddam’s rocket boys had test fired a SCUD. I awoke from a sound sleep in the barracks to the sight of “Chin” in full chemical ensemble, screaming “Incoming! Get your shit on!”

They test-launched another about an hour later, so we jumped into our gear again. We found out later that both missiles had landed in an opposite corner of Iraq, and never left Iraqi airspace.

We had to jump into our chem gear again on 21 Dec 1990 when Israel test fired a Jericho missile.

On Christmas morning, Saddam again launched a SCUD that landed in Iraq, and we jumped into our gear.

The next day he tested his longest range SCUD yet, the al Hussein (also Anglicized al-Husayn). Again we donned our chemical gear.

Throughout the war, we wore our charcoal infused chemical suits, less the mask and gloves. When we got an Alarm Red, we would throw on our masks, then pull on a poncho over everything. The Iraqis had something called “Dusty Mustard,” a granular dry chemical agent that could work its way through our chem suits. The ponchos allegedly would shield our suits from Dusty Mustard, at least a little.

We had upgraded from MOPP (Mission Oriented Protective Posture) level 2 (GCE, Groundcrew Chemical Ensemble jacket, pants, and boots) to MOPP level 4 (MOPP 2 plus mask, poncho, and gloves) for six different Alarm Reds after the war began, from 17 through 20 Jan 1991.

Each time we saw and heard no incoming. After about 40 minutes or an hour, they would give the “All Clear” signal, and we would downgrade to MOPP 2 (or what we euphemistically called MOPP 2V, for ventilated, unzipping to let the sweat out).

Nothing had ever come of it. We got a little more lackadaisical about it each time we jumped into our gear, only to be given the “all clear” a few minutes later, when the SCUDs landed somewhere else (like Dhahran or Israel).

Then came what would later be known in the annals of air defense as the Battle of Riyadh.

After midnight on 21 Jan 1991, about nine SCUDs were launched toward Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Toward us.

I say “about” because no one is actually sure how many. In extending the range of the al Hussein SCUD, the Iraqi rocket scientists had added a fuel section that weakened the SRBM structurally. That made each al Hussein tend to break up on re-entry and became 3 or more inbound objects. “Our screens lit up with all these missile fragments that were coming at us,” said Col Thomas Smith, in command of the Air Defense effort for Riyadh.

Even with their recently upgraded ABM (anti ballistic missile) software, the Patriot radars could not tell which part was the warhead, which was a motor, and which was a mostly empty (but still dangerous if it fell on you) fuel tank.

Consequently, they fired at everything falling out of the sky. 32 Patriots–almost the entire on-hand inventory of 36 (3 batteries of 3 launchers each, 4 missiles loaded in each launcher)–rose into the sky from the batteries defending Riyadh (ours at KKIA, one at an air base in Riyadh where our sister flight from Warren AFB was stationed, and one at an oil refinery on the south edge of town) that night.

We were in the Hole when we got that Alarm Red. As we bailed out of the Hummer and started climbing into our gear (somewhat without enthusiasm), Worm pulled up and climbed out of his Suzuki. He walked over to where we were struggling to get our ponchos on over our masks and suits.

The air raid siren was blaring.

In any language, Worm’s eyes and tone of voice said “What the hell’s going on?”

I was about to pull the hood of my poncho around the filter and face piece of my MCU-2/P gas mask when we heard loud BOOMs from the southwest. They came from the opposite side of the huge international airport, but we still felt as much as heard them.

The noise took me back, suddenly, to 1972 . . .

. . . when I was a 10 year old at an “open house” at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. We were watching the launch of a surface to air missile. I had been expecting something like the Saturn V Apollo launches I’d seen in the previous few years: a continuous, roaring sound, as the missile slowly left the pad and accelerated as it went up.

But, suddenly, BOOM!

And it was gone.

One moment it had been sitting there, upright, on the ground; the next, there was just a column of smoke from its exhaust reaching straight up, high into the sky.

Two decades later, at about 0113 hours on 21 Jan 1991, I was still holding the head opening of my poncho open with my fingertips, about to work my masked head, filter first, through that tiny hole. Peering out of that hole, holding it open with my fingers on each side, I turned toward the source of the noise: the Patriot battery on the opposite side of the airport.

Then came the WHOOSHes! and the flames.

Two Patriot missiles arced up across the airport and then went vertical over our Hole.

Explosions, like white thumbprints in the sky, flashed and were gone.

Directly, I mean directly, over our heads.

I looked at Dave.

Dave looked at me.

I pulled my poncho the rest of the way on–with somewhat more enthusiasm than I had previously been displaying–and looked at Worm. His eyes were as wide as mine.

My first responsibility was to my fire team, but here was this human being, this comrade in arms, with no mask on and no suit. For all we knew, Sarin could have been raining down from the sky at that very moment.

I grabbed Worm by the arm and dragged him to his Suzuki patrol vehicle.

I shoved him into his driver’s seat, leaned in across his lap, turned off the heater fan, and flipped the lever to recirc (recirculate cabin air, rather than taking in fresh air from outside).

I rolled up his window and slammed his door shut.

He raised a hand, jabbered loudly in Arabic, and drove off–at an angle–out of the Hole.

Then I turned to my fire team. We mounted up, and drove around looking for debris. Bits of SCUD (or Patriot) on the runways or taxiways could easily be sucked up by the KC-135Rs huge, low slung, high-bypass ratio turbofans, so it was important that we find any FOD (foreign objects) on the tarmac.

We came to find out that the Iraqis had far more SCUDs, and far more mobile launchers, than our intelligence had initially estimated. They had gotten quite adept at hiding them under overpasses and in neighborhoods and at moving them as soon as they launched. They’d had plenty of practice during the War of the Cities with Iran.

As time went along, we got smarter about how we responded to the SCUDs. We posted a liaison with the British (Ambassador 2). The Bloke chain of command had fewer intervening levels of bureaucracy, so they got the word a few minutes before we received official notification through our own chain that there was inbound high explosive attached to unguided rockets. Of course, to say so would be bypassing our own chain of command, a no-no. His code phrase on the radio for incoming was “75, 75, 75” which told us all we needed to know.

After 22 Jan 1991, instead of donning our complete chemical ensembles first, we would race to the nearest culvert or bunker with overhead cover. A piece of SCUD (or Patriot) falling on you would probably kill you, whether or not it was tainted with poisonous chemicals.

Then, and only then, we would make sure we were completely suited up in MOPP 4. Most of us had our gloves on by the time we got there. Jason, our driver, had to play catch-up.

One of my greatest concerns after we adopted the “race to the nearest hole and jump in it” TTP (tactic / technique / procedure) was that we would be bunkering down during a SCUD attack when sappers would launch a coordinated ground assault on our base. Fortunately the bad guys never capitalized on that bunkered down vulnerability.

Till we figured out the rough patterns in the timing of their SCUD attacks, it seemed like I would always have just filled my canteen cup with some MRE coffee when the Alarm Red would come, and the siren would blare its haunting rising and lowering moan. If I didn’t want it in my lap while Jason played Dukes of Hazzard with our Hummer, I had to pitch my Lifer Juice out the window.

We got our hot water at a Fire / Crash / Rescue outfit on the edge of our area. It was run by retired firefighters from the UK. Seemed like most of the fire fighters were Korean and Filipino TCNs, but Blokes ran the shop.

Britts like their “brew” (tea), and they had a teapot. We would frequently stop at the fire station to boil some water for our MRE coffee or hot chocolate.

Eventually, the attacks tapered off a little, and seemed to arrive on a schedule.

“Wanna roll by the fire station and get some coffee?” one of us would suggest.

“What time is it?” I would ask. “Half past midnight? Naw, let’s wait till after the Zero One Hundred SCUD attack.” Of course, it was never really that regular, but acting like it was made us feel like old pros.

When we’d roll up to the fire station after the All Clear was given, our nerves were still a little on edge. I’d pour the hot water into my tin canteen cup, with just a little bit of tremor in my fingertips.

The Chief of the fire station was the oldest guy I remember seeing at KKIA. He looked ancient to me, but in retrospect, he was probably about the age I am now. He would sit at his desk (I seem to recall huge picture windows behind him), smoking a cigarette. Nothing seemed to flap him.

“Mind if I ask you a question, sir?” I ventured after one of the nightly SCUD scrambles.

“Please,” he replied, motioning for me to take a seat.

“Well, it’s just that–Don’t these SCUD attacks bother you? You seem totally at ease. Is it that you’ve grown fatalistic, because most of your life is behind you?” (Before I turned 60 myself, the 60s seemed near the end to me).

He smiled at the assertion. “Well, you see, Yank, I was a boy of 14 when Hitler’s V-2s were falling on England.

We would get 5 or 6 [V-2s] at a time raining down on us. There was no warning. One moment you’d be bicycling down the road, and the next, buildings would be falling down around you.

We didn’t have any Patriots to intercept them [he pronounced the “Pat” of Patriots like “Patrick”]. So this is really quite mild by comparison.”

From Sep 1944 to Mar 1945, 1,115 V-2s had rained down on the UK, killing 2,754 and maiming 6,523 severely. 1,524 V-2s fell on Antwerp and other targets in Europe, killing hundreds more.

Sitting across the desk from that fire chief at KKIA, who had been a combat veteran at age 14, I thought it was a pretty sad commentary on humanity that half a century later we hadn’t advanced as a species beyond lobbing ballistic missiles at the other guy’s population centers. The Iraqis and the Iranians had shot SCUDs at each other in the War of the Cities, Mar – Apr 1988. The Soviets had fired SCUDs and Frogs at the Afghans. More recently, starting in 2015 (seven decades after Hitler’s V-2 attacks) Houthis, aided by Iran, have been launching SCUDs and other missiles at Saudi Arabia.

Actually, not even missiles. Although its flight path is parabolic, technically making it a “short range ballistic missile” (SRBM), the SCUD, like the V-2 it was copied from, lacked internal guidance. It was basically just a rocket. All the aiming took place before launch.

If I recall correctly, the SCUD had a CEP (circular error probable, the radius inside which half the warheads would fall) of 500 meters. There was a 50% chance that a SCUD would impact inside a circle a click [kilometer] wide around its target. Useless for, say, taking out a command bunker, but useful to sow terror when aimed at an area target like a city–or an airport full of tanker jets.

There were also several field hospitals set up at our base. Not to hide legitimate military targets (the aerial refuelers that supported our air campaign) behind the red crosses on the hospital tents, but because the proximity of the runways to the hospitals was essential for aeromedical evacuation of the wounded from the front, and trans-shipment to more definitive care at better hospitals in-theater and farther to the rear (like Ramstein, Germany).

SCUDs aimed at the airport terminal were as likely as not to hit any one of several hospitals. The inbound SCUDs cared little more about the medical facilities than they did about the fact that we had females working at KKIA. Congress still hadn’t permitted females to serve in so-called “direct combat roles,” but the SCUDs did not differentiate. Yet another example of the disconnect between DC’s perception and reality.

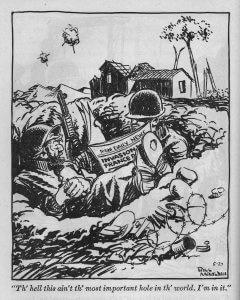

Stormin’ Norman Schwartzkopf described the SCUD as a tactically “insignificant” weapon, and perhaps he was right. But years before, in a military history class I took, one of the questions on the final was “What was the most important battle of the Civil War, and why?” I had prefaced my answer with “To the participants, the most important battle is whichever one they happen to be in at the time. However, in terms of its effect on the outcome . . . ”

“To a soldier in a hole, nothing is bigger or more vital to him than the war which is going on in the immediate vicinity of his hole.”

–Bill Mauldin, 45th Infantry Division cartoonist in WWII

Our sister flight from FE Warren AFB in Wyoming had stayed in Riyadh to guard the airbase there when we moved north to KKIA. One of my troops from before the war was proned out, taking shelter under his patrol vehicle when a nearby SCUD impact blew the windows out of his truck.

His hair turned grey after that.

He was a square jawed, handsome young man. That salt ‘n’ pepper hair made him appear more mature than his youthful face. I understand the combination made him quite popular with the ladies after the war.

Eventually, the SCUD attacks tapered off. They picked up again in February.

On 25 Feb 1991, a SCUD slipped to the side of a Patriot battery’s defensible “footprint” and landed on a barracks in al Khobar, a suburb of Dahran in Saudi Arabia. The 500 kg warhead killed 28 Americans, including Army Reserve Specialists Christine L. Mayes, Adrienne L. Mitchell, and Beverly S. Clark: women who were directed by Congress to avoid combat roles and stay safely “in the rear with the gear”–which is just where they got killed. That SCUD maimed 98 more Americans.

We almost never saw the inbound SCUDs. They came in fast, several times the speed of sound, from the edge of space. Usually, our only direct evidence of their existence was their scattered parts that would be found laying around when the sun rose the next day. I do remember watching one (or part of one; possibly a fuel tank) burning, high and to the southeast of us, as it tumbled over and over out of the sky after being hit by a Patriot.

That verse in the Star Spangled Banner about “the rocket’s red glare” has never meant the same to me since.

To this day, whenever I see somebody wearing the intercepting arrows of the 11th Air Defense Artillery Brigade, especially if the patch is on the right (combat) sleeve, I go out of my way to buy them a drink or a meal. Those Patriot missileers saved all of our butts.

We still saw Worm from time to time out there, but after that first bad night, the so-called Battle of Riyadh, he must have found a place to seek shelter as well. Never figured out where he went.

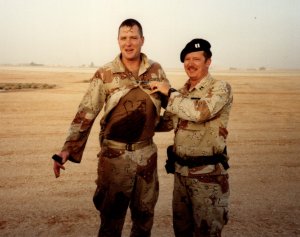

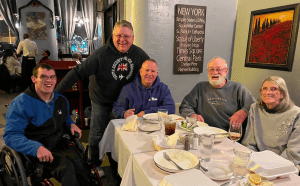

I’ve completely lost track of Jethro . . .

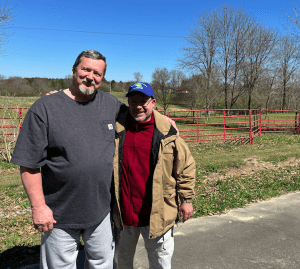

but recently visited T-bone . . .

. . . and Jase.

Even after all these years I still get a warm feeling whenever I reconnect with folks from the 1703 GDF(p).

But if there’s one person in the world I’d like to catch up with, it would be Worm.

I feel more kinship with Worm than with the vast majority of my own countrymen who never served.

For that matter, though I didn’t like them much at the time, I feel more kinship with those poor bastards whom Saddam ordered to launch SCUDs at us–and were quite often pounced upon by Coalition aircraft within minutes of sending their rockets aloft–than I do with these spoiled Antifa hipsters and their ilk, who’ve never heard a shot fired in anger, never known a day of hunger, and yet are filled with loathing for all things this great land has given them. Or with these Boogaloo idiots who claim to be defending traditional Western values from anarchy and mob rule, but many of whom are really just white supremacists.

“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers . . .”

–Shakespeare, Henry V, Act 4

Wherever you are today, Worm, I wish you health, happiness, and enough wealth to afford three wives, regardless of how many you wound up with. Fi Amanillah, rafiq.

–George H, TSgt, USAFR (ret)

Appendix I:

Best — TDY — Ever

The closest I personally came to getting killed over there was in a traffic circle in Riyadh. The second closest we came was when the crew of our KC-135 freedom bird tried (several times) to stick a landing in the severe cross winds of the Azores on the way home.

We were the second Security Police flight to arrive, and the second to leave after the war ended. When MSgt Galpin told us anybody who wasn’t ready to leave by our estimated departure time was going to be left behind, we went into a mad scramble to pack up our gear. It amazed me how much junk we had accumulated in a little over 6 months. That very day I got a gigantic care package from my buddy Max M, who was leading Army patrols in the forgotten DMZ of Korea while the world’s attention was focused on Arabia.

Max’s latest care package was loaded with peanut M&Ms, other pogey bait (snacks), books, and magazines. I gave almost all of that stuff away to the Hodgies who worked with us.

We gave some equipment to our allies or left it for other security flights, but a lot of the more dangerous hardware, like Claymore mines, we blew in place. I’ll refrain here from making any comments about our shameful rout from Afghanistan.

Every boom box at J-1, our barracks, was blasting Motley Crue’s “Home Sweet Home.” The lyrics are kind of inane, and I thought the hair bands of the ’80s were mostly silly, but it sounded great at the time.

Just as a whole host of songs is associated with the Viet Nam era, we had our Desert Storm minstrels and ballads. I read somewhere that Paula Abdul was the most popular singer among the Gulf War troops. Can’t count the number of times Jon Bon Jovi told us he was a cowboy who rode on a steel horse with a loaded six string on his back. I never realized how much “Home Sweet Home” was associated with our Middle Eastern tour till about a year after we got back.

We were riding out to the missile field in a “six pack,” an X-cab pickup with bench seats fore and aft, or perhaps in a Suburban. It took an hour or two to get to even the closest launch control centers, and even longer for most. We spent 3 nights out there and came back on the fourth day, if you didn’t get snowed in. We were always a little subdued on the way out (and tired on the way back). Four of the six of us had NOT deployed to Desert Shield / Storm.

Motley Crue was singing “Home Sweet Home” on the radio, and the four who had stayed in the ‘States had solemn poker faces. I looked over at the other guy who had deployed. He was the grey haired, square jawed guy who’d taken shelter under his truck when the SCUD landed nearby. Listening to that Motley Crue song, he was wearing a shit eating grin from ear to ear, and nodding slowly. Subconscious, Skinnerian operant conditioned response. Like Pavlov’s dogs salivating when they heard the bell.

To this day, that song makes me bust into a smile.

During a recent visit to his home, Jason and I reached a consensus: despite its many hardships and hazards, Op Desert Shield / Desert Storm was the single best TDY (temporary duty assignment away from one’s home base) either of us ever had in the Air Force.

Why was it a great TDY? Six reasons:

FIRST of all, the jefes were more a lot more concerned about mission accomplishment than they were about nit-noy rules. That was quite a change from the Iron Fist of the Strategic Air Command back home, with its checklist mentality and lack of flexibility.

SECOND, we were blessed to have excellent flight-level leadership.

MSgt Galpin, our Flight Sergeant, was a been-there, done-that, no-nonsense senior NCO who knew what he was about. He was our real-life equivalent of “Gunny Highway,” who had fought in a shooting war before some of us were born. Among his spoils from Viet Nam was a French MAS rifle with a bullet hole through the stock–from the round that took out it’s previous Viet Cong owner.

Galpin had a great sense of humor.

Right after we got to Riyadh in 1990, MSgt Galpin was doing roll call at guard mount. He didn’t know all of us yet, and was struggling with a few of our names. “Lo-BROCK-ee-oh?” Galpin asked.

“It’s Low-BRAY-co,” Sgt Todd J. Lobraico corrected him.

MSgt Galpin was careful to always pronounce it “Lo-BROCK-ee-oh” after that, just for fun.

Before the ’91 war kicked off, we were scouting the civilian side of KKIA, making plans for its defense. As we gazed into a large wadi (a canyon-like arroyo, or dry river bed) on the edge of Echo-14s planned patrol area, Galpin told us, “They could move an entire division down this, and you wouldn’t even see it.”

“I’ll keep an eye on it, Sarge,” I replied.

“You’re not reading me, George,” MSgt Galpin corrected. “I want you to have enough fuel and water in your Hummer at all times to reach the coast, if we get overrun and have to bug out of here.” The Voice of Experience spoke. Galpin had been in ‘Nam during one of the major enemy offensives (Tet in ’68, the Eastertide Offensive in ’72, or the Spring Offensive of ’75, I can’t remember which now).

Capt Terry Morgan, our Flight Commander, was a prior enlisted cop, knew ground defense “from muzzle to butt plate,” and cared a lot more about us and our coming home than he did about his personal performance reports. He’d actually worked for Galpin as an Airman, before he got his commission. When he got selected to lead one of the two deploying flights, Morgan got to choose his own Flight Sergeant–so he picked Galpin, an NCO whose leadership he had experienced from both above and below.

I had issues with some of the decisions made at the group or wing level, but both of our Alpha Flight leaders ran interference and stood up for us.

I’ll count SSgt (later, I heard, Chief Master Sergeant) Ron Parsons, of the 90 SPG mobility section, among the leaders we were blessed to have with us. Parsons was truly the secret to our success, and not just as a logistician, at which he excelled.

One night, an M60 gunner from another fire team was working with us on Echo-14. Each fire team bunked together, so after a while we started rotating days off to one person from any given fire team at a time so they could have a little privacy and a break from each other. The guest gunner was unhappy, and didn’t want anybody else in that Hummer to be happy. He was getting into it with everybody–especially Jason. He was really pushing Jason’s buttons, on purpose, and it was starting to work.

When my best efforts at peacekeeping failed, I requested that SSgt Parsons, who was our area supervisor that night, pay us a visit.

After he locked that acrimony down–he ordered them not to speak to each other at all if they couldn’t say anything civil–Parsons pulled me aside, and taught me some things about leadership that I’ve never forgotten. He said that if there’s discord on the team, it’s the leader’s fault for letting it happen. I’ve tried to put that, and other things Ron Parsons taught me, into practice since.

THIRD, what we were doing was important. Guarding nukes in Nebraska had been important, but for the most part they guarded themselves, under tons and tons of concrete. The tankers and field hospitals at KKIA were very necessary for the war effort (the tankers ended up being more needed than the hospitals, God be praised), but unlike ICBM silos, both were highly vulnerable.

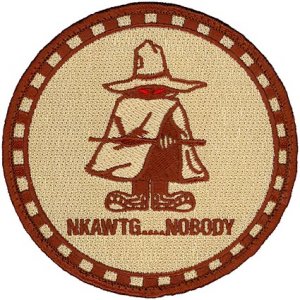

Everywhere around an aerial refueling outfit, you saw murals and morale patches of “the Phantom” (an image parodied from the mascot of the F-4 Phantom II fighter pilots) holding an aerial refueling boom.

The boom was a telescoping fuel nozzle with wings, hanging off the back of a tanker aircraft.

The boom operator, or “boomer,” lying on his or her belly in the back of the KC-135, would literally fly the nozzle of the boom till it was directly over the refueling receptacle on the receiving aircraft, then punch a trigger that would shoot it into the receptacle and lock it in place for the duration of the fuel transfer.

Refueling in midair is a challenging, slightly dangerous set of maneuvers for all participants. It was even more dangerous at night, in bad weather, when the aircraft are laden down with bombs and sluggish to respond, or if there are a lot of other aircraft around. A confluence of all those conditions existed on the first night of the war–plus, nobody was using their formation lights.

The complicated aerial refueling dance is one thing that makes our Air Force capable of striking anywhere in the world, and it is magnificent to behold. In the opening sequences of the film Doctor Strangelove, director Stanley Kubrick set aerial refueling footage to waltz music.

Underneath the Phantom mascot, with his boom, was written “NKAWTG . . . Nobody.”

Nobody Kicks Ass Without Tanker Gas.

Nobody.

Flying tankers wasn’t glamorous, but it was absolutely essential to the war effort. As the A-10 pilots liked to say,

“You can shoot down all the MiGs you want, but if you return to base and the lead Soviet tank commander is eating breakfast in your snack bar, Jack, you’ve lost the war.”

Saddam’s tanks weren’t much of a threat to our flying tankers, so far “in the rear with the gear” (at least not after the first few months of Desert Shield, when enough soldiers and Marines had arrived to block them). We were about 300 miles from Kuwait.

In the unlikely event we had to face off against armor, or had to take out what would later be called a “technical,” or had to re-take one of our own bunkers, each of our Humvees had a compliment of LAW (light anti-tank weapon) rockets.

But with their soft underbellies full of fuel and complex gas-turbine engines, our KC-135s were certainly vulnerable to sabotage and small arms fire from sappers and insurgents.

Who was there to stop that?

We were.

The 261 security police men and women of the 1703rd Ground Defense Force, provisional.

Along with about 70 French commandos of the 206th GIA . . .

. . . 30 British policemen of the 26th Squad, RAF Regiment . . .

. . . and 35 Kiwi (New Zealand) air police.

Like every Security Policeman (now every Security Forces troop) at every airbase knows, if the base does get threatened or (God forbid) overrun, we would be the last out.

The View from the Top

I was qualified on the ’60 and would man the machine gun from time to time, just for a change of pace.

I remember one night when we convoyed from Juliet One (our barracks and armory) to KKIA for change-over; I was riding in the gunner’s hatch. Just after we rolled through Golf One (the main gate), the convoy split, traveling diverging tangents like the top of a Y. Half went to guard the King’s side of the airport, and our half went to guard the civilian side. The lead vehicle went left, the one behind it right, the one after that left, and so on. Not a complicated maneuver, but it looked very well orchestrated–magnificent, even–as each rolled off the hard top and began kicking up a dust trail across the desert, clearly visible in the moonlight.

As I bounced along in that Hummer’s top hatch in my flack vest and helmet, wind in my face and dust goggles over my eyes, watching the convoy bifurcate with the feed cover of that powerful hog under my palm, a belt of 7.62mm hanging out of the feed tray, I felt part of something much bigger and far more important than myself.

Mine ears have felt their pounding throb, a hundred thousand strong

A mighty airborne legion, sent to right the deadly wrong

But now it’s only memory; it only lives in song . . .

—Air Corps Lament (to the tune of The Battle Hymn of the Republic)

THE FOURTH REASON that TDY was good for me was personal. It was like a reunion with classmates I’d known at the Air Force Academy. See Appendix II for details.

THE FIFTH REASON was the outpouring of support we got from all corners of our society, from the president to the poorest taxpayers. My favorite “To any soldier, sailor, airman or Marine” letter was just a piece of blank paper with lipstick smooch prints from the tellers at a bank.

We also got letters from WWII vets in nursing homes. Those were quite humbling, as their losses and trials had been staggering in comparison to our cakewalk.

“I will, however, tell you just one thing about the war, my first story and my last. I was asked by some American friends to search out the grave of their son near Bastogne. I found it where they told me I would, but it was among 27,000 others, and I told myself that here, Niven, were 27,000 reasons why you should keep your mouth shut after the war.”

–Actor David Niven, when asked about his experiences in WWII

Our commander in chief had been shot down in the Pacific during WWII. Lt (jg) George Herbert Walker Bush bailed out of a burning Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bomber. Both of his crewmates were killed. He floated around in the ocean for some time, wondering whether the Japanese or the sharks were going to get him first. Unlike Lyndon Johnson, who micro-managed the Viet Nam war from the Oval Office, Bush wasn’t about to play silly games with our lives. Bush gave his military leaders a clear achievable mission–evict the Iraqi squatters from Kuwait–and gave us troops what we needed to do it.

Viet Nam vets congratulated us for turning around our losing streak. Praise from ‘Nam vets was also quite humbling, for different reasons. First, they’d had to fight with both hands tied behind their backs, due to stupid rules of engagement. Our generals had been lieutenants in Viet Nam, and weren’t going make the same mistakes again.

The other reason support from the ‘Nam vets was so humbling is because they had been treated like pariahs when they got home. The American public treated us like gods when we came back–we got parades–in part, I think, because the Baby Boomers who were running the show by that time felt guilty about having spat upon the ‘Nam vets.

Our Security Police group commander back at FE Warren, Col Chris Gugas, also provided as much support, logistical and otherwise, as possible. He ensured we got to trade our ancient M17 gas masks for the latest MCU-2/Ps.

Col Gugas also signed for brand new, and quite expensive, Phrobis M9 bayonets with wire cutters to replace our older, and less multipurpose M7s (see Bayonets).

After we got home, he gave us time off that wouldn’t be charged to our leave accounts. “I don’t want to see any of you for a month. Just let your orderly rooms know where you’ll be,” Col Gugas said, “in case this thing heats up again and we need you back.”

He had walked in with a brown cardboard box under his arm, and set it down without mentioning it. “In the old days,” he said, “I’d have had a drink with you guys. But that sort of thing isn’t allowed now.” When he walked out, he left the mysterious box. Curiosity got the better of us. Inside the box were enough plastic cups for all, and a bottle of fine Scotch. MSgt Galpin led us in a toast before we scattered to see our loved ones.

Support from the friends, family, and random members of the public was awesome. I got letters from folks I’d barely spoken to in the decade since high school. But nothing meant more to me than support from my lady.

My girlfriend–who has since become my wife of 33+ years–wrote to me EVERY SINGLE DAY I was deployed. We had been dating long distance for 3 years, and she was going to join me in Wyoming when she graduated from college in December of ’90. But I’d been in Saudi for over 3 months by then, and had no idea when (or even if) I’d return. She sent me a photo of her in her cap and gown, with a note on the back: “Now who’s waiting for who?“

THE LAST REASON it was such a great TDY was that every member of that 44 man flight had been hand-picked for competence and motivation.

On 02 Aug 1990, I’d been on duty as a Flight Security Controller at Charlie One, a Minuteman III ICBM launch control facility east of Harrisburg, Nebraska. The news was showing video of Iraqi tanks rolling through the streets of Kuwait City. I had done a 6th grade report about Kuwait during the first oil crisis (in 1973), so unlike many watching that broadcast, I’d actually heard of that tiny country and had some idea of where it was.

The desk phone rang. It was the 90th Security Police Group’s assistant mobility NCO. “Hey, H,” he asked, sounding a little hard-pressed, “is your Chem Warfare up to date?” meaning: had I taken the annually required training on defense against chemical attack sometime since August of 1989?

“Pretty sure,” I replied. “You’ll have to check with the back-office weenies at 89 MSS” [specifically, the 89th Missile Security Squadron Training NCO, who kept track of stuff like that and scheduled things like recurring firearms qualifications or Chem Warfare or Laws of Armed Conflict training] “to be sure. Why do you ask?“

“No reason. Gotta go. Bye!” He hung up.

I looked back at the tanks on the TV screen. It didn’t take long to put 2 and 2 together.

The 90 Security Police Group was tasked with sending two 44-man flights to support what would initially be dubbed Desert Shield. The two commanders had, between them, 1100 gun-toting security policemen to choose from.

Many times, when asked to send people TDY, a squadron will fess up with its slackers and troublemakers.

This was different. We could very well be going to war. Col Chris Gugas, formerly a B-52 pilot in Southeast Asia and then commander of the 90 Security Police Group, gave the two flight commanders carte blanche to cherry-pick whomever they wanted.

They hand-selected people who had:

- previous combat experience (like T-bone, SSgt Scott Christensen, and SrA Ed “Corky” Hunter had the year before in Panama, and MSgt Mark Galpin decades before in Viet Nam),

- been laterals from the Army and Marines (like Ron Bradshaw, who’d been in Army artillery, and Mike Cloud, former USMC scout-sniper),

- served previous tours in Europe or Korea (like Scottie Christensen and SSgt Jeff Jones), and therefore had extensive training in defensive countermeasures against chemical attack,

- received additional Airbase Ground Defense (ABGD) training (as several of us, including A1C Carlos “Macho” Camacho, had gotten at Volant Scorpion in Arkansas),

- been members of the FE Warren Emergency Services Team (the base SWAT team, including SSgts Tracy Huff and Steve Pre’tat), and

- those of us from the Olympic Arena missile combat competition teams (including A1C Mike Sullivan, TSgt Craig Smith, A1C Jason Bilyeu, SSgt Doug Lineen, and me).

Maybe not the best of the best, but certainly among the top 10% of the group, at least when it came to airbase ground defense. TSgt Nick Liberti, who came over as a replacement later, had also been on Olympic Arena.

And just about all of us–especially Galpin and Morgan–had a sense of humor, which made even the worst of times more tolerable.

It wasn’t always sunshine and roses. When you work with the same people, all day, every day, for months on end, folks sometimes get on each other’s nerves.

But to this day, I love each and every one of those guys we deployed with. I wouldn’t have wanted to be anywhere else, with anybody else.

Appendix II: USAFA Reunion in Riyadh

I had flunked out of the Air Force Academy in ’84, and wound up enlisted in the Security Police. Most of my classmates became pilots or navigators on aircrews. I rarely ran into any of them at FE Warren AFB, which was a missile base and didn’t even have an active runway.

Many of my age cohort went into the tanker biz, and the 1703rd AREFW(p), the largest tanker outfit in the world, brought many of them together from all over. Here are a few of the ones who stand out most in my old feeble mind:

Deo

Deo Lachman was a fellow “preppie” from the USAFA Preparatory School class of ’81.

I did not have the grades to get directly into USAFA. The Air Force Academy has a prep school for people like me, and also for athletes, prior enlisted people who’ve been out of school for a while, and minorities who might not have had access to as many educational resources as people from more privileged social strata. “Preppies” are an even smaller, tighter-knit subset of the small, tight knit society that are Service Academy alumni. Deo and I spent 10 months together at the prep school, trying (and ultimately succeeding, where 60% of the preppies did not) in earning admission to the Academy itself.

Deo pronounces his name “DEE-oh,” but of course I couldn’t resist singing “DAY-oh, DAY-ay-ay-oh,” like the lead-in to Harry Belafonte’s “Banana Boat Song,” whenever I greeted Cadet Candidate (and later, Cadet and then Lieutenant) Lachman. I was privileged to sing that intro to him again in the chow hall at KKIA, and even to fly with Deo on a KC-135 incentive ride or two.

The (Blue? Straw? Ras?) Berrys

One of my squadron mates in the 31st “Grim Reaper” cadet squadron was Brian Berry. Brian was a thin, bookish looking guy, but appearances can be deceiving. Brian was what we called a “RECONDO stud,” having been through the Army’s exchange cadet program at the 4th Mech Infantry Division’s Primary Noncommissioned Officer course, called PNCOC (“pea nock”). PNCOC was also called RECONDO, because they taught long range reconnaissance patrol (RECONnaissance commanDO) techniques as a vehicle for teaching leadership. Army RECONDO grads were eligible to become instructors on the USAFA Tactical Leadership Decisions course, and most of us did.

I hadn’t seen Brian since January of ’84. One day in Saudi I came out of my barracks room, which was adjacent to our Security Police armory, and standing there in line I bumped into what appeared to be Brian in an Army captain’s uniform.

The Captain rank was right–Brian was two classes ahead of mine at the Academy. The face was Brian’s. The name tag said Berry. What was with the Army uniform?

On rare occasions, a service academy grad will seek and obtain a commission in a different branch of the military. It is possible, for example, to graduate from West Point as a 2Lt in the Air Force or an Ensign in the Navy, but such cross-commissionings are rare, notable, and usually on a one-for-one exchange basis with the other Service Academy. I had been to Brian’s commissioning ceremonies and had not remembered him cross-commissioning. So startled was I to see him thus, I even forgot military protocol and rather than addressing him as Captain Berry I blurted out, “Brian?“

“You know my twin brother?“

No shi–fooling. I actually ran into Brian’s twin brother on the other side of the planet. If memory serves, he was assigned to our Patriot battery.

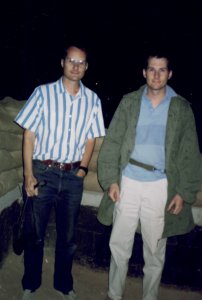

Brian was somewhere in that fracas as well, and came to visit his brother and me one night when I was pulling rooftop marksman duty. Brian was passing through on his way to somewhere Stateside.

I was loathe to give my undeveloped film to local developers, for fear some fifth columnist might use my tourist pictures as a source of intel about our base. Brian took several of the rolls I had on hand and held onto the photos for me till later. Many of the shots you see in this article were developed at Brian’s time and expense, for which I will ever be in his debt.

Kelly

Kelly Michels was another of my squadron (and class) mates from USAFA. He was flying KC-135s, and we spoke as frequently as our separate career paths would allow.

Rae

Rae Anne Noyes was also in the USAFA class of ’85. Although we were both in 4th Group, on the west side of Sijan Hall, she was in a different squadron and we didn’t know each other well.

We did wind up with our arms around each other on several occasions–but not romantically.

Or hitting each other. We were in the same Phys Ed classes.

At 5’4″ and barely 120 pounds, I was the only guy there who was even close to Rae’s weight class, so the coaches had us sparring against each other a lot in Wrestling and Boxing. I can’t remember if we paired off against each other in Judo. I do remember that she consistently defeated me quite soundly in Racquetball.

Rae wound up in the KC-135 biz, in the 1703 AREFW(p), so I saw her occasionally in passing.

Appendix III: The Cantonment Area

Foreigners living in Saudi Arabia often live in compounds, where they can practice their own ways (crucifixes, halter tops, shorts) without interfering with the social mores or Sharia law practiced outside their compounds throughout the land of the Two most holy Mosques.

When we arrived in Saudi we took over a series of buildings set aside for TCNs: the Pakis, Sri Lankans, Filipinos, (dot) Indians, Koreans, and other third country nationals the oil-rich Saudis imported to do most of their grunt work. Gradually, we fortified it with fences and barbed wire. As I said, we were not allowed to dig into the Kingdom’s most holy soil, but there was a solution to that: fence posts in portable concrete footers.

About a year after the war, I got off active duty and cross-trained as an aeromedical evacuation crew member in the Wyoming Air National Guard’s C-130 outfit. One of my additional duties was making sure that our flight nurses and other AECMs kept up their small arms qualifications. Although Wyoming is in Free America, where most everybody has guns, firearms are somewhat antithetical to those who practice medicine. Most of our personnel were nurses, paramedics, and EMTs in their civilian careers.

I drew this poster from memory and used it to show my fellow AECMS that during the 1990 – 91 Gulf War, personnel of the Air Transportable Hospital (ATH in the upper left corner of this diagram) had to man (and wo-man) their portion of the perimeter–with M16s–each night. Their defensive fighting positions (DFPs, which were also LP/OPs, listening and observation posts) are marked with orange circles in this diagram.

I include it here for historical reference.

North is at roughly 7 o’clock in this diagram. The airport was east (left) of this cantonment area, or housing compound. Our own barracks, J-1, was north of this compound (below this diagram) as were the trailers housing the GDF Group commander (and, if I recall correctly, key staffers), but we secured this compound as well as the airport and our own barracks.

Several of the cinderblock buildings had wrap-around balconies. The French, accustomed to places where the other guys hate them, hung chain-link fence from their roof and balconies. That would have forced the shaped charges of RPGs to go off prematurely, before striking the building itself. We sandbagged the balconies at J-1, in case we had to fight from there.

The ECP, or entry control point, was of course manned by Security Police.

Eventually, we had more people than we had housing, so there were tents set up in the SE (top left) corner of the compound. Can’t remember if they were GP mediums or the newer temper tents. We held our guard mount briefings before each shift in a GP medium tent outside J-1. There’s a funny story about how we moved that tent “the Galpin way.” The Air Transportable Hospital–one of several military hospitals around the airport–was a series of temper tents strung together.

Some of the aircrews were housed at a hotel south of the airport. I got over there once to make a brief long-distance call to my honey on a pay phone; it cost me over a hundred dollars.

I don’t remember where the chow hall was, but it was somewhere in that compound. Once, in what would now be termed sexual harassment (but was received with a smile at the time), Gil Chavez led a group of guys in a Top Gun Officer’s Club-like chorus of

“Oh baby, you

You got what I need

But you say he’s just a friend

You say he’s just a friend”

. . . for a lady he admired in that chow hall.

I remember an Army sergeant telling me I should remove the magazine from my M16 in the chow hall. I had just come down from a rooftop and was still on duty, only in a different place. I told him that as soon as they changed the Air Force regulations requiring me to have a charged (loaded) magazine in my weapon while on duty, I’d be happy to comply with his request.

The OP / CSR (observation post / counter-sniper rifleman) location most desired by the guys, at least during the day, was the southmost (top of the diagram), on the ground crew barracks across the road from the pool. There wasn’t much scenery, though, as it was what we called a “sausage fest.” The vast majority of the troops in-theater were men.

At night, my personal favorite OP / CSR was the Army barracks, as they always had a pot of coffee on downstairs, and I would occasionally head down to their charge-of-quarters desk to tank up on lifer juice. I remember apologizing to somebody on the top floor in case I kept him up at night pacing back and forth on his roof. He told me he slept better hearing me up there, knowing an armed guard was watching over them.

There were breezeways between each of the four buildings, and a central “quad,” or courtyard, in each group cluster. There were command trailers in the courtyard of the Army barracks for Delta Battery (now, after watching Col Smith’s interview, I think they were for all the Patriots in the Riyadh area) of the 11th Brigade, 43rd Air Defense Artillery. I remember seeing civilian contractors and uniformed 11th ADA troops going in and out of them; perhaps Col Smith was there as well.

My least favorite OP / CSR duty was on the barracks building that had an AF admin / finance / comm / HQ unit in it. There were lots of antennas on the roof that I was sure were irradiating my internal organs. I tried to stay on the opposite end of that roof while I was up there.

There was a recreation hall that we shared with the other TCNs, somewhere between this cantonment area and J-1. I remember watching a fascinating Saudi-approved documentary about how shoes are made in there. Prime entertainment.

There was also a gym. I’m not much of a gym-rat, but I tried to work out now and again. We had a few “corn fed boys” with power-lifter bodies, like Doug Lineen and “Corky” Hunter, who worked out all the time. One of the memories that sticks with me is of the undernourished Sri Lankans staring at them in awe as they did pull ups.

Appendix IV:

1703 GDF(p) or 1703 AREFW(p) Reunion

Chances are, if you’re reading this, it’s either because you were there, or somebody you love was, or you need to get a life. Just kidding. But it’s probably a whole lot more interesting if it takes you back to the day.

For those of you who were there, we should have a reunion sometime. Tracey Huff has been trying to put together a cop group reunion, but other than trying to establish a contact list, we haven’t made much progress. Please reach out if you are interested. There is a facebook page for the whole wing.

Epilogue: A Birthday Present–and the Ultimate Sacrifice

I got called up as a reservist in 2008 and sent to Kuwait. By that time I was, ironically, back in the Security Forces (I was a firearms instructor at a Combat Arms firing range, but I deployed as a “straight leg” cop). I was stationed at Ali al Salim AB, west of Kuwait City. The aircraft shelters there still had big holes in the tops that were punched by Coalition bombs during the ’91 Gulf War. There was also a wall with multiple pockmarks from bullet holes, where, local legend had it, the Iraqis had lined up Kuwaiti prisoners and shot them.

Several times, our Kuwaiti hosts had us over for dinner. We dined in posh homes, and on rugs in almost equally posh tents–the well-to-do Kuwaiti equivalent of a picnic. I drank chai with less well-to-do bedouins who herded camels in the desert around our base and throughout the Saudi-Kuwaiti trans-border region, towing their trailer, which looked like a gypsy caravan on gigantic tractor tires, with a Toyota pickup truck.

All-in-all, the Kuwaitis were very gracious hosts. Every single one I met had a father, an uncle, or a brother who was killed during the Iraqi occupation. As with any other society, there were those with differing opinions–one of the 9/11 hijackers was a Kuwaiti–but the ones that I spoke with loved Americans. We were there supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom, and during the course of OIF our troops up north sometimes found it necessary to shoot back at Iraqi insurgents. As far as our Kuwaiti hosts were concerned, killing Iraqis was the Lord’s work.

Back here in the ‘States, my family has an old globe. It still has a “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics,” “Yugoslavia,” and “Czechoslovakia.” There are two Germanys, but only one Sudan.

On my 61st birthday, my son gave me a gift of recognition.

He pointed to Kuwait on the globe, and said, “See this? It still says ‘Kuwait,’ thanks to you.”

I had never thought of it that way. What he said really got me in the squadron patch. I thanked him for saying so, then added, “Me and about half a million other Coalition troops” . . . most of whom lived and worked in much worse conditions, and took far greater risks, than we did at KKIA in ’91.

As did those boys and girls in Somalia, and the Afghan / Iraq wars which followed ours.

Like many of us 1703 vets, Todd Lobraico later went into civilian law enforcement. He also wore the blue beret of the Security Police (subsequently renamed Security Forces) for many more years in the Air National Guard. I heard he made Chief.

Todd Lobraico’s son, TJ Jr, followed his father’s footsteps into the Security Forces. He served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Sadly, TJ was killed in a gun battle outside the wire of Bagram Air Base, Afghanistan.

We all made some sacrifices in our careers, but Todd Senior gave more than all the rest of us combined.

“I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of Freedom.”

–Abraham Lincoln, in a letter to Lydia Parker Bixby, 21 Nov 1864

Select Sources

In refreshing my memory and bouncing it off of recorded histories, I made use of the following sources of information:

Atkinson, Rick. Crusade: The Untold Story of the Persian Gulf War. Houghton Mifflin Co, 1993.

Carus, W. Seth. Ballistic Missiles in Modern Conflict. Center for Strategic and International Studies, 1991.

Hallion, Richard P. Storm over Iraq: Airpower and the Gulf War. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992.

Mauldin, Bill. Up Front. The Word Publishing Co, by arrangement with Henry Holt and Co, 1945.

Mills, David R. 1703 AREFW “A” Flight FE Warren AFB. Dave Mills was 2nd Squad’s leader, and quasi-official flight historian. He compiled a series of primary sources (for example, portions of our Security Police “blotter”) into a booklet outlining the Alarm Reds we went through, dates of significant incidents, names of the people on that deployment, etc. It has been my go-to source for information about what happened locally to us, when.

Reaching Globally, Reaching Powerfully: The United States Air Force in the Gulf War. No author is listed for this 58 page white paper published in September of 1991. It was handed out at the Red River Valley Fighter Pilots Association (“River Rats”) reunion in 1992.

Smallwood, William L. Strike Eagle: Flying the F-15E in the Gulf War. Brassey’s, Inc, 1994.

Smith, Thomas E. “Our Screens Lit Up”: Shooting Down SCUDs During the Gulf War. The West Point Center for Oral History. Interview videotaped 29 Apr 2022. Smith graduated from the USMA in 1971 and commanded the Patriot batteries around Riyadh. Although the launchers were also located in Riyadh proper and south of town, the command center for all three batteries was at KKIA, so we and Col Smith “sure as hell chewed some of the same dirt,” as Clint Eastwood said in Heartbreak Ridge. The first hour and 15 minutes of this video deals with Col Smith’s experiences as a cadet at West Point and with his career before Desert Shield. The most relevant parts of Col. Smith’s story to this one occur between 1:20 and 1:45 in the two hour and twelve-minute video.

Sturkol, MSgt Scott T. “20 years after operations Desert Shield, Desert Storm: Vets say tanker contribution ‘is what made the air war work’.” amc.af.mil, 10 March 2011. I did not read Sturkol’s article until 2026 (well after I initially drafted Worm’s story). When we served in Saudi, we were told our unit, the 1703 AREFW(p), was the largest operational tanker unit in history. The tanker vets quoted in this article make the same claim about the 1709th, which operated out of Jeddah. The 1709th operated 76 aircraft, manned by 126 aircrews (the crews need to sleep; the planes don’t) and 2,000 maintenance personnel (don’t know if that number includes the cops who guarded them). All the numbers actually fluctuated during the buildup and the war (one KC-135 had 2 engines–on the same wing–ripped off by turbulence during the war; the crew managed to land her, but she probably wasn’t “operational” for the duration), so both claims may have been true at one point or another. Further, throughout the buildup, the war, and after, SAC used its tanker fleets to suppement MAC’s transports, so tankers were flying in and out of bases all over the region, all day, every day.

Stuteville, Joe. “Riding Out the Storm.” American Legion magazine (Vol. 130, No. 6), June, 1991, pp. 28 – 31 & 66 – 67, especially pages 30 – 31.

Much love back H! Very few days go by without thoughts of those months.

Siff