TacMed Terms

In the movies, if good guys are shot at all, it’s in the shoulder. The bullet misses everything vital. Immediately after the fight, their arm is in a sling, and they are exchanging witty banter with another lead character. Rarely is there any paperwork, nor emergency surgery, nor physical or emotional pain, nor months of physical therapy.

My limited experience with gun battles is, there is a very messy period of cleaning up afterward. Your “tactical” training should prepare you to start addressing injuries before the smoke clears.

Here are some terms you may hear during your tactical medical education.

All images of patients, injuries, or treatments in this article are simulated, unless otherwise noted. Relevant TacMed terms are capitalized for emphasis; we’re aware that’s not grammatically correct. This article is a work in progress; more terms are added as time goes along.

Abrasion–a scrape, like road rash. May lead to infection, and in severe dases, Hypothermia, but usually the greatest danger of Abrasions is staining the furniture.

Active Killer, Active Shooter, Active Violence–often with the words Incident or Event attached, are all variations on a fairly obvious theme. There are some nuances. Often, when the media speaks of an active “shooter,” they may mean a bomber or a madman wielding a bladed weapon, while never missing out on a chance to blame guns for the actions and insanities of people. “Tactical” Medicine–what this glossary is primarily about–often takes place in the general vicinity of the incident while the violence is ongoing, or “Active,” and / or in the immediate aftermath. When we train to practice medicine in that toxic environment, we generally speak of Active Violence, since killers and wannabe killers get to choose what means or combination of means are brought to bear upon the innocent. It should be noted, though, that when a drug dealer is shot during a business transaction, and the victor in that skirmish splits, that scene is no longer “active,” although, again, it is often reported as an “active shooter event” so that you will live in fear of random violence. In fact, despite the headlines, most violence is very directly targeted at specific individuals for specific reasons that make perfect sense to the perpetrators. Your chances of becoming a victim of violence go astronomically down if you are not drunk, on drugs, or involved in the drug trade.

Anatomical Landmark–something on the body (including head, arms, and legs) you can see or feel that will tell you where underlying organs and structures are, or where to perform a technique. For example, when giving Abdominal Thrusts (the Heimlich Maneuver) for choking victims, we place our fist just above the Navel (belly button).

Arterial Pressure Point–The human body has places where arteries cross over bones. Pressure against those points can pinch the artery, reducing its flow.

The Brachial Pressure Points are on the insides of the upper arms, under the biceps. The Femoral Pressure Points are at the top outer corners of the pubic region, about where the Inguinal Folds end (the tops of the V of the groin).

Artificial Respiration–See Rescue Breaths

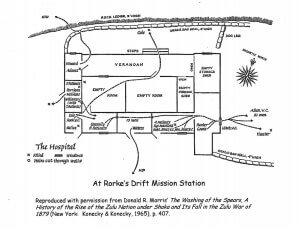

Asymmetric Evacuation / Rescue–a silly name for a very valid concept. If you can’t get to a casualty because the routes are under fire or blocked, it may be possible to get to them, or get them out, by busting through a wall or a window. When Zulus over-ran the hospital at Rorke’s Drift, the doors to most rooms opened only to the outside. Patients and soldiers were able to escape by cutting holes in the walls.

You can do the same by kicking through interior drywall between the studs (which should give you about 16″ to squeeze through).

At Robb Elementary in Uvalde, Texas, the main north-south hallway was a Warm Zone–guns were pointing into it from both sides. Officers evacuated students from the classrooms on either side (except the two the killer had shot up, one of which he still occupied) through the exterior windows.

Auditory Exclusion–a subconscious defense mechanism whereby the brain shuts down auditory input it deems as unnecessary when you are scared to death. People have reported hearing “pops,” or nothing at all, when they were in fact hearing very loud gunfire up close.

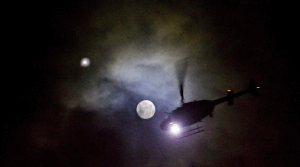

One evening in northwest Tucson, a police officer shot a man who was trying to kill him with a shotgun. He was keeping the bad guy covered and requesting backup. Knowing no other officers were nearby, the officer flying air support landed a helicopter in the intersection behind the officer and ran over to him. When the pilot grasped the officer’s shoulder and asked if he was OK, he responded “Aren’t you flying tonight?” So tunneled in was he on the guy who had just tried to kill him with a shotgun, he had not even heard a helicopter landing yards away.

Auditory exclusion does not always happen. I remember distinctly wondering when that auditory exclusion I’d heard so much about was going to kick in, when a bad guy was firing shots with a rifle about 40 yards from us. The sound of gunfire by good guys and bad was painfully loud to me as I ran closer to it.

The significance of Auditory Exclusion in Tactical Medicine is that your patient may not hear your questions or commands when they are still in the Fight or Flight Reaction, if somebody was just doing a pretty good job of trying to kill them. This is on top of any injuries they might have susteined (even in non-violent situations, a semi-conscious patient my be responsive to touch, but not verbal stimuli). You may need to repeat questions, speak louder, get their attention through touch, or use hand and arm signals.

Bad Guy–a term often used in our TacMed training and literature to indicate a Threat Actor. Although it may seem to be a patriarchal leftover of a less politically correct age, we still use the term Bad Guy for several reasons, including:

- Mass murderers are still, almost always, persons with Y chromosomes;

- The term has fewer syllables than “bad person,” which is just silly; and

- Due to common historical usage, “bad guy” is easily recognized and understood to mean a Threat Actor.

Understanding is, after all, a main goal of training and education, so we try not to use too many confusing words. We even create glossaries like this one for words which might be misunderstood. We mean no disrespect to any female or trans mass murderers. If you have two X chromosomes, or you feel like you should, and you go about slaughtering children, we will respect your gender, or chosen gender, while we shoot you in the face. But we will still sometimes refer to you as “the bad guy.” Nothing personal.

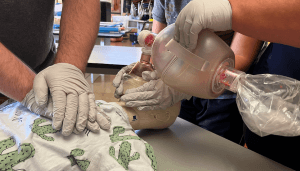

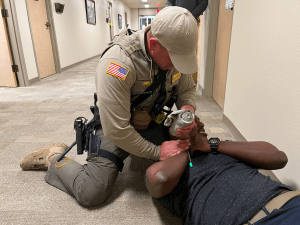

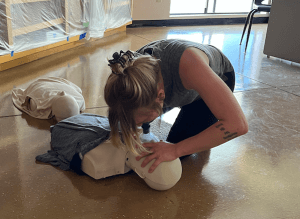

Bag-Valve-Mask (BVM)–A device for giving Rescue Breaths, consisting of a squeezable, semi-rigid bag, a facemask, and a one-way valve. BVMs allow us to put a higher concentration of oxygen into the patient (20+% if using room air, with up to 100% if the BVM is hooked to an oxygen hose) than mouth-to-mask ventilations (about 14% O2). BVMs do not require that you get your face into the other person’s face area, reducing the risk of disease transmission. BVMs are awesome tools but they require specific hands-on training. See BVMs for more info.

Bandage–material (usually cloth) used to affix a Dressing to a wound. Since the brand name BandAid came out, people have often used the term Bandage to mean a Dressing. It’s not a big deal, but for clarity of semantics, it may help to remember this:

- We dress a wound with a Dressing

- We keep the Dressing in place by wrapping the body, limb, or head with bands of material

BATH Assessment–A simplified version of the MARCH algorythm. The BATH acronym stands for:

- Bleeding

- Airway

- Tension Pneumothorax

- Hypothermia

BATH is the order in which we look for and treat injuries. When we scan a downed person for severe bleeds, we start with the legs (place where you can bleed the most THAT WE CAN TREAT) . . .

then the neck and arms . . .

then the torso (front of their chest and abdomen). As we roll them into the Recovery Position to protect their Airway, we check their back for bleeds as well.

Initially, to prevent or slow the onset of Tension Pneumothorax, we slap a (preferably Vented) Chest Seal over any holes between the neck and the navel.

Field treatment of existing Pneumothorax may include Needle Decompression.

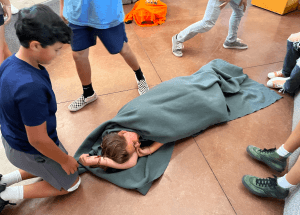

We complete the BATH assessment by wrapping the patient up in a blanket to keep them warm.

Blind Packing–see Wound Packing

Blunt Trauma–the kinds of injuries one gets from a baseball bat, steering wheel, or golf club.

BorSTAR–Border Patrol Search, Trauma and Rescue. The USBP equivalent of USAF’s pararescue.

Bulky Dressing–is more or less what it sounds like. Before wrapping a burned or broken hand, you can place a roll of gauze in the palm of that hand to keep it in its natural shape. You can wrap a doughnut or pyramid of material around an Impaled Object to stabilize it. If you don’t have any bulky gauze, you can use cloth, for example a rolled or wadded t-shirt.

BVM–See Bag-Valve-Mask

Cardiac Tamponade–see Pericardial Tamponade

Cardio-pulmonary Resuscitation–see CPR

Care Under Fire–Somewhat limited TCCC protocols for treating patients in the Hot Zone, while you are taking incoming. There are only a few things you can do, because your priority in the Hot Zone is winning the fight. You are authorized to perform a few medical interventions, like putting on a tourniquet, because if you’re bleeding out and you wait till after the gunbattle ends to treat it, it’ll be too late. Called Direct Threat Care in TECC.

Casualty—TCCC word for a wounded person (usually, but not always, a wounded allied soldier or enemy combatant, but sometimes a civilian caught in the crossfire). Called a Patient in TECC.

Casualty Collection Point (CCP)–In a Mass Casualty Incident (MCI), it’s a good idea to collect the bodies of those still living somewhere safe near (but not in the middle of) an evacuation route. This enables medics to be less spread out, to prioritize care and evacuation of the most needy (Triage), and to consolidate their gear for distribution as needed. Litter bearers can bring supplies into the CCP and then take patients out, bringing more supplies when they return for more patients.

During large, involved MCIs, you may need several CCPs, but establishing CCPs should NOT be a priority for the first medical teams to enter the Warm Zone. Rather, treat life threatening conditions you find as you go, and move on to the next victims. If you can move them quickly to a safer location please do, but do not park and play over them treating non-life-threatening injuries or preparing them for transport.

An example of what the first rescue teams to reach the patients should NOT do at this stage is applying a pressure dressing over a packed wound, which will be a great idea later on, when we’re ready to Transport them. Rather, assign a bystander, if any, to apply pressure over the packed wound and move on, seeking more victims who are bleeding out and need more immediate attention. Subsequent teams can start collecting patients into CCPs, conducting secondary assessments for things the first teams might have missed, applying pressure dressings, and packaging patients for Transport.

In tactical situations, the CCP must have its own dedicated security element. After establishing security, the very first thing your protectors must do is come up with a game plan: what will we do when (not if) this Warm or Cold Zone turns Hot? Who will stay and who will go if we spot a Bad Guy nearby?

CAT (Combat Application Tourniquet)–A lightweight, compact tourniquet that uses Velcro. During the GWOT (Global War on Terror) the US Army adopted the CAT as its officially issued tourniquet. The main advantage of the CAT is that the material is stiff enough that it easily makes a loop that stays more or less open, which makes it one of the easiest tourniquets to put on yourself one-handed, in the event your opposite arm gets injured.

The windlass of the CAT is plastic, and has been beefed up from the original versions. Real CATs are made by North American Rescue. Be wary of cheap knock-offs you can find on eBay and other internet shopping sites. The knock-offs may or may not break the first time you try to use them.

Central Nervous System (CNS)–The brain, brain stem, and spinal cord. Hits to the CNS have the greatest likelihood of resulting in the immediate incapacitation of your assailant. CNS hits may not be necessary with rifles or shotguns, but they may be the only thing that stops the fight in a timely manner when all you have to fling at the bad guy are pistol bullets, which are relatively underpowered.

The body is essentially a life-support system for the brain. Other than making the sure the patient’s brain continues to get oxygen and nutrients long enough to get them to a hospital, the most important part of the CNS we are concerned with in prehospital medicine is keeping the nerves in the neck from getting damaged (see Cervical Spine Stabilization below).

Cervical Spine Stabilization–Keeping the head in-line with the rest of the spine to reduce the risk of paralysis. The cervical, or “C-spine” vertebrae are in the neck. C-Spine Stabilization can be very important, if, say, the casualty was injured by a bomb blast that threw her up against a wall. If, on the other hand, he suffered Penetrating (stabby pokey shootey type) Trauma (injury), the bullet or knife either hit his spine or it didn’t. If it missed, you probably don’t have to worry too much about the C-spine. If the bullet hit one of the vertebra in the spine, the damage is probably already done.

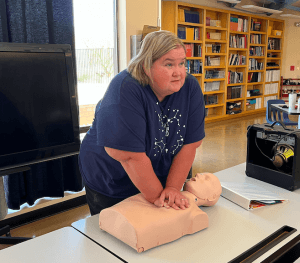

Chest Compressions–The most important part of CPR. Filling in for a non-working heart by squeezing the heart between the sternum and the spine.

The goal of Chest Compressions is to keep the brain and other vital organs alive until the heart can be Defibrillated (usually with an AED, Automated External Defibrillator).

Chest Seal–see Vented Chest Seal

Command of Execution (see Preparatory Command)–The second command. The first command tells us what to do, the Command of Execution tells us to do it NOW. For example, the LIFT of “Prepare to lift, LIFT.”

Comorbidity–a separate disease process that adds another nail to one’s coffin. Usually, Comorbidity refers to sicknesses. For example, a lung cancer patient who also has cirrhosis of the liver.

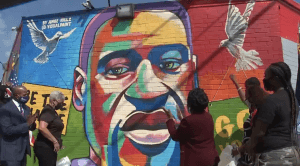

In the TacMed world, we sometimes use Comorbidity to refer to external, traumatic, or self-inflicted contributing factors. The tragic case of George Floyd was a series of compounding Comorbidities.

Internal Comorbidities:

- Severe heart disease, including blockages of his coronary arteries and enlargement of the heart

- Fentanyl and methamphetamine onboard

- Panic attack. Although the causes of panic attacks are Pychosomatic (in one’s head; for Floyd it was brought on by the realization that he was going back to jail), the effects of panic attacks are very real, including a bounding heartbeat and shortness of breath. This shortness of breath occurred before they even got him near the police car, and caused him to say “I can’t breathe” over and over.

External Comorbidities:

- Prone position, which has been know since the 1990s to cause Positional Asphyxia

- An officer kneeling on his torso, contributing to his Positional Asphyxia

- An officer kneeling on his neck / between his shoulder blades, which did not affect his airway, but could have slowed the flow of one carotid artery, each of which supplies about half of the blood to the brain

- His head was near the exhaust of a running automobile

It’s probable that no single one of the above factors killed him (the officer kneeling on his neck also breathed the same exhaust and did not die, but he was a little farther from it). The combination of the above comorbidities became a landslide that his body could not survive.

While the officers had zero control over his internal comorbidities, and had a duty to restrain him, they could absolutely control the way they restrained him, and to a lesser extent, where they restrained him. He may have been hard to move but it would have been easy to shut off the engine, and hence the exhaust. Rolling him into the recovery position might have made it easier for him to get up and run away but would also have made it easier for a man saying “I can’t breathe” to breathe. Sitting Floyd up would have relieved the pressure on his torso and made if easier for him to breathe while he was conscious. After Floyd lost consciousness, they could have started CPR, or (if he was still breathing) rolled him into the recovery position.

Controlling those external comorbidities might have saved his life. We can adjust our tactics and treatments to prevent or at least reduce similar incidents in the future. For more detailed analysis, see A Case Study in Comorbiditiy.

Compensatory Shock–When the body is severely injured, it can fight back for a while. If the patient is losing blood, for example, the arteries can constrict to keep the blood pressure up. Most of the time, the body can compensate for about an hour. We call that “The Golden Hour.” Eventually, they start to lose the battle and Decompensate.

Confined Space (in rescue)–An area, such as the inside of a tanker truck’s fuel cells, where there is limited room for rescuers and their equipment, the entry is perhaps too narrow for standard gurneys, and / or there is limited oxygen / ventilation. Confined Space has a different meaning when fighting; see the Glossary of Gunspeak.

Contusion–a bruise. Usually indicated by discolorations, but Contusions can be internal, and not visible from the outside. They are often accompanied by swelling.

Contusions of the brain can be dangerous because when fluids rush to those tissues to assist with healing, the swelling brain is trapped in the hard skull and can get crushed.

CPR (Cardio-pulmonary Resuscitation)–A series of life saving rescue skills primarily geared toward keeping a person alive after their heart has stopped. The most important of these techniques is Chest Compressions.

CPR is not indicated when the patient looks like Swiss cheese. Nor is CPR usually our first choice in MCIs. There are exceptions. On 27 July 1996, during the Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia, when the bomb went off in Centennial Olympic Park, two people died. One was Alice Hawthorne, hit in the head by shrapnel (a 3″ masonry nail). CPR would not have helped her. The other fatality was a news cameraman, Melih Uzunyol, who ran over there and suffered a fatal heart attack. CPR was absolutely indicated for him, although performing it might have kept you from treating the other 111 people who were injured in the blast. CPR has a lower chance of success than, say, putting a tourniquet on a severely bleeding limb.

Dead Space–An area that cannot be seen and / or engaged with direct fire. In kinetic situations, it’s a good idea to drag your patient into some dead space–preferably behind some cover (something solid that will stop a bullet), but at least out of sight (and hopefully, out of mind), before treating their injuries.

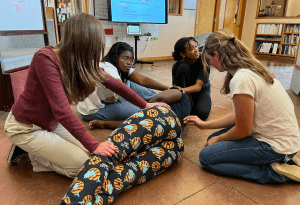

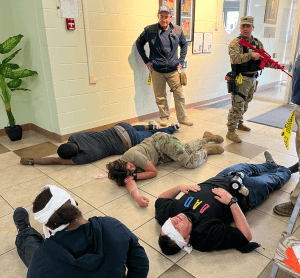

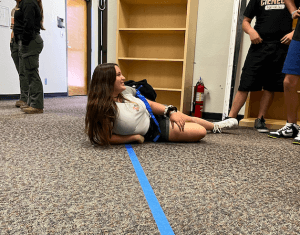

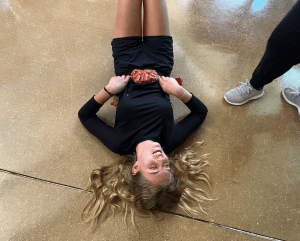

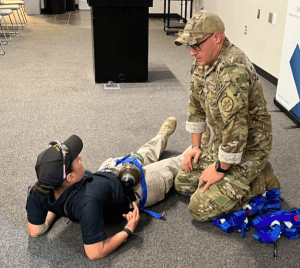

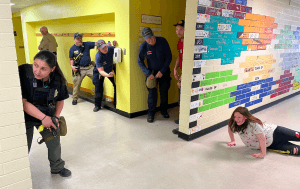

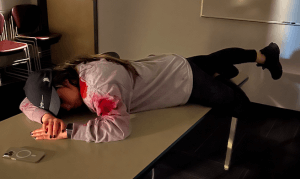

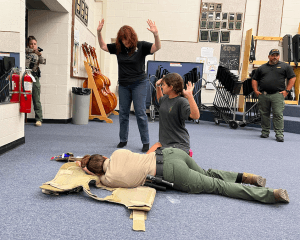

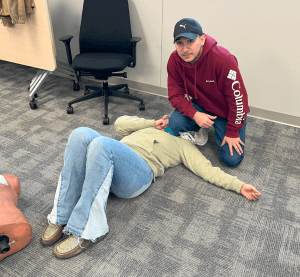

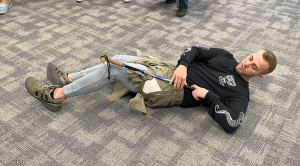

The portion of this classroom to the right of the blue tape on the floor cannot be seen from the windows by the door. The portion to the left of the tape can. Students who had treated this “injured” role player left her head and shoulders (and one of their own backs) exposed to observation or targeting from outside the classroom, by not moving her completely within the dead space before administering first aid (the blue tourniquet) to her “wounded” arm. Dead Space in this context could also be thought of as “a safe location” or “a position of cover,” although it may not protect you from fire through the walls. Image from an Active Shooter Workshop for educators, put on by Pima regional School Resource Officers (SROs), assisted by ICSAVE.

Decompensatory Shock–When the body systems begin to fail, unable to keep up with blood loss or temperature loss of lack of oxygen, the body’s ability to keep up (Compensate) eventually runs out of steam. When this begins to happen, medics may say the person is “crumping,” “crashing,” or “circling the drain.” Decompensatory Shock is truly shock. Compensatory Shock is about to become Decompensatory Shock, if we don’t fix the problem.

Defibrillation–stopping a quivering (Fibrillating) heart, so it can start beating again the proper way (top to bottom). Usually done with an electrical shock sent through the heart by a Defibrillator.

Diaphragm–a bell-shaped muscle attached to the bottom of our rib cage. When the Diaphragm contracts, it flattens out. This expands the volume inside our chest cavity, creating negative pressure in relation to the air outside, drawing air into our lungs. When the diaphragm relaxes, it returns to its larger bell shape, pushing air out of our lungs. Because the diaphragm is attached to the bottom of our rib cage, you should apply an Occlusive Dressing, preferably a purpose built, Vented Chest Seal to any Penetrating Trauma between the neck and the navel.

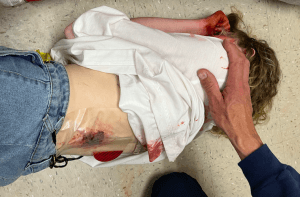

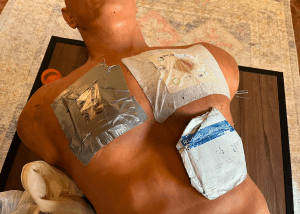

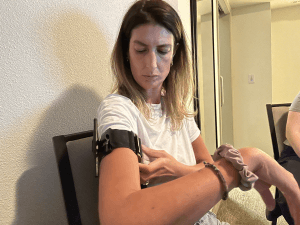

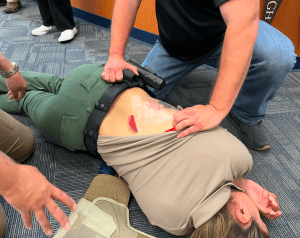

Imagine a flat, two-dimensional plane running through this patient at the bottom of her ribs (about the narrowest part of her waist). Since everything north of that plane may be lung cavity, we place a Vented Chest Seal (like the red-tabbed NAR HyFin Vent on her left side) over any GSWs or stab wounds above her belly button.

Direct Pressure–our “Go To” for bleeding control. Direct pressure is easy to explain and delegate to the less trained in an emergency. “Push hard right there, and don’t let up.”

Direct Pressure works better on limbs, junctional areas, and in the pelvic region than elsewhere on the body.

Pushing too hard on an abdomen or chest can make it difficult for the patient to breathe, and more importantly is not likely to slow, much less stop, serious bleeding from those areas.

Firm but NOT HARD pressure is OK on an abdomen or chest, say with a washcloth, to keep the carpet from getting stained.

Direct pressure to a head can actually hurt the patient if there is a brain injury with a compromised (cracked) skull. An injured brain needs room to swell without crushing brain tissue. One thing that saved Gabby Giffords’ life was the fact that her skull was compromised in two places, allowing the damaged tissue to swell (Dr. Peter Rhee, Trauma Red, p. 180).

Probably the best way to apply direct pressure is with a knee or shin. That frees up the rescuer’s hands for other tasks, and is much less fatiguing.

Directed Packing–See Wound Packing

Direct Threat Care–The TECC equivalent of TCCC’s Care Under Fire. The medical protocols are virtually identical; the main difference is, in TECC, your main goal while taking fire is to stop the threat. This can be accomplished by isolating, containing, or neutralizing the bad guy(s). In TCCC, the main goal while taking fire is to defeat the threat, which is almost, but not quite, the same thing. See Care Under Fire for the few recommended Hot zone medical interventions.

Doff–To take something off, like gloves, other Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), a biohazard suit, or a chemical ensemble. For most PPE, there is a specific way to remove it without contaminating yourself in the process. As opposed to Don.

Don–To put something on, specifically PPE. Don protective gear BEFORE you need it, and leave it in place. As opposed to Doff.

Dressing–what we place directly against the wound. As opposed to a Bandage (see), which holds the Dressing in place.

EDC (Every Day Carry)–What you have on you on a more or less daily basis. It might be handgun, and / or a folding knife, and / or a cell phone, and / or spare magazines, and / or house keys, etc. Your EDC should include a tourniquet and compressed gauze. If you only have room for one item, a 3″ wide Ace wrap can be used to form a field expedient tourniquet or even to pack a wound.

An Ace wrap is not the ideal tool for either job, but it can do both, as well as wrapping a sprained ankle or strapping on a splint. Because this one tool can do so many different things, it may be there when a tourniquet isn’t.

Remember, “If it’s not within arms’ reach when you need it, it might as well be on Mars,” so a 3″ Ace wrap might be part of you EDC.

Evacuation Care–describes specific protocols for when you are removing a patient and transporting them to definitive care at a hospital. Evacuation Care is ideally rendered in a Cold Zone. Pretty much anything that a bystander, first reponder, EMT, or Paramedic can do day-to-day can be done in Evacuation Care.

Evisceration–An abdominal wound resulting in part of the intestines protruding through the hole into the outside air. Although whatever caused the evisceration might have lacerated mesentery arteries, punctured vascular organs like the liver or kidneys, or even cut the aorta (all of which are VERY life threatening), eviscerations themselves are not usually going to kill your patient. Usually, only a knuckle-sized piece of the bowel, if any, protrudes, but sometimes it can look like something out of Game of Thrones.

What can kill your patient is hypothermia or infection, both of which may result from improperly treated (or untreated) evisceration. Also, if the abdominal muscles pinch back together they can restrict blood flow to the exposed portion of the bowel, which can kill it. The resultant surgical shortening of the patient’s digestive tract may mean that the patient won’t be able enjoy Filiberto’s burritos quite as often as they used to. NEVER SHOVE THE GUTS BACK IN. If you are many hours from help you can try hooking a finger inside each end of the laceration, pulling up on the abdominal wall, and seeing if the guts pull themselves back in. If they do, you can approximate the edges of the wound and tape them together. Otherwise, pile the guts on top of the abdomen, rinse off any gross contamination (gravel, dirt, twigs) with copious amounts of clean lukewarm water, apply a moist dressing, and then wrap the dressing–NOT TOO TIGHTLY!–to keep it moist and in place. Keep them warm. See Field Expedient below for more Evisceration treatment options in austere environments.

Femoral Pressure Points–Two of the four major Arterial Pressure Points where we can slow circulation to a limb by squeezing the main arteries up against an undelying bone. To use a Femoral Pressure Point, push with a fist, knee, or shin on the upper outer corner of the pubic region (the end of the “V” formed by the Inguinal Fold) on the same side as the bleeding leg. Make sure your shin is right along the Inguinal Fold, where the bottom hem of a fairly modest ladies’ swimsuit would be. See Femoral Triangle below for an excellent diagram of what you’d be trying to push (the artery & corresponding vein) against what (the pubic bone in the front of the pelvis, the ring of bones that hold our abdomen up).

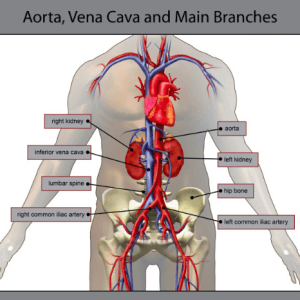

Femoral Triangle–should perhaps be called the “Femoral Wishbone.” The Femoral Triangle is in the pelvic region, from where the Aorta bifurcates left and right into the Iliac Arteries to where the Femoral Arteries enter the legs. It also includes the corresponding veins which mostly parallel those arteries. Pushing HARD on the inguinal fold, where the Inguinal ligament crosses over the artery, to squeeze the vessels against the underlying bone, should slow blood flow to the limb significantly, buying you time to apply a tourniquet.

The Femoral Triangle is also an alternate target if you need to shoot someone but their chest and head are protected by armor or behind a small child hostage. Our landmark to aim for is either or both of the top ends of the “V” of the groin, about where the major vessels cross the pubic bone. Even if you miss the arteries (which is more likely than not) the bullets should get caught in that big catcher’s mitt of the pelvis behind. Shattered bone should disrupt the suspension system of your bad guy. See Where to Shoot a Kidnapper for more.

Field Expedient–An improvised substitute for the real thing. If you don’t have gauze, for example, you can pack a wound with a T-shirt instead.

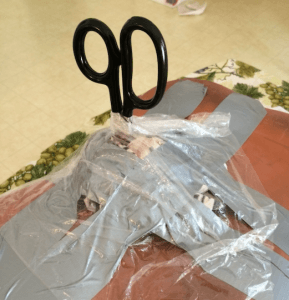

You can keep a dressed evisceration moist and clean and hold it in place with Saran type wrap, a Field Expedient occlusive bandage. But again, don’t wrap it too tight. Make it just snug enough to keep the protruding bowel from spilling out.

Fine Motor Skill–is something requiring dexterity of our fingertips. Before all the advances in robotics and laparoscopy, brain surgery required fine motor skill (it probably still does). The problem is, the deeper we are into the “fight or flight” reaction, the more our body will shunt blood away from our extremities and into our major muscle groups (like your thighs, so you can run farther faster) and our core organs (primarily your heart and lungs, to power those major muscle groups with the oxygen they need and to circulate around all the adrenal chemicals our body is doping us up with). Accordingly, we should avoid training to perform (and counting on performance of) Fine Motor Skills during or immediately after a fight, although some Fine Motor Skills may not be avoidable. Not to be confused with Complex Motor Skills, although some instructors say “complex” when they really mean “fine.” See also Gross Motor Skill in the Glossary of Gunspeak.

Golden Hour, The–Our bodies are designed to compensate when we’ve been injured. After about an hour, though, most Trauma victims will become Decompensatory: their body will lose the fight to keep blood pumping to their vital organs like the brain. Obviously, actual mileage varies with the fitness of the person and the nature and extent of their injuries. We can buy them time by establishing Hemostasis (stopping their bleeding), laying them horizontal in the Recovery Position, and keeping them warm (see Hypothermia). Regardless, the sooner you get them to Definitive Care–a hospital–the more likely they will be to survive. See Transport, Compensatory Shock, and Decompensatory Shock.

Gross Manipulation (of an injured limb)–Moving the body part a great deal. As a general rule, we try to avoid Gross Manipulation of any injured body part, but in a tactical / mass casualty environment, where you may need to move quickly from one patient to the next to the next to the next, don’t be afraid to, say, prop that leg up on your thigh or even over your shoulder to get that tourniquet on or to check the underside of the limb quickly for additional life threatening injuries.

GSW (Gunshot Wound)–Injuries from a firearms projectile (bullet, slug, buckshot, birdshot) that enters the body. If the gun was fired up close (they almost always are), GSWs may include injuries from burning powder (black Stippling around the wound) or from Sabots or Wads that hold the projectile inside the barrel. With contact or near contact shots, there may be Stellate blast injuries from the expanding burning gasses that push the projectile(s) out of the barrel entering the wound.

Hemostasis–When blood is going round and round INSIDE the body, rather than leaking out. If someone is bleeding out, and you stop it with a tourniquet, then you have achieved Hemostasis.

Hemostatic Agent–A chemical that speeds up the clotting process. There are basically two kinds:

- Clay-based, and

- Shellfish-based.

Clay-based Hemostatic Agents depend upon the patient having a healthy clotting mechanism. They work fine on soldiers, who tend to be young and healthy. Older people on blood thinners do NOT have a healthy clotting mechanism. Shellfish-based agents work better for them.

The original Hemostatic Agents came in powder form and had some drawbacks. Imagine dumping dirt in a rapidly flowing stream: much if not all of it gets washed away. If it wasn’t yet soaked with blood, the powder on top tended to blow away in brisk winds (such as a landing MedEvac chopper).

It could also blow into a medic’s or patient’s eyes, which was a problem since the volcanic rock-based Quick Clot heated up, burning flesh or eyeballs when it got wet. The shellfish-based powders, initially, may have exacerbated pre-existing shellfish allergies. The burning and allergic reactions are no longer a problem, but there is still the nature of powders to deal with. As we say,

“It’s NOT magic pixie dust.”

Immediately after dumping it into a wound (not sprinkling it on the wound like in the movies) you needed to apply direct pressure with dressing ot T-shirt.

The powder problem was solved by soaking gauze in it and letting it dry (see Hemostatic Gauze).

Hemostatic Gauze–Thin, open-woven fabric or muslin (gauze) impregnated with a Hemostatic Agent (see above). Hemostatic Gaze is currently the best of both worlds. While you might have to hold direct pressure on a packed wound for 10 minutes or more with regular gauze, Hemostatic Gauze might clot the wound in 3 minutes. Biggest downside is the expense. For the cost of one hemostatic dressing you could buy an entire box or regular roller gauze. Plus, they have an expiration date; regular gauze can be used indefinitely.

READ THE INSTRUCTIONS for your particular brand of Hemostatic gauze. Some require you to remove them completely from the wound, if they become saturated with blood. Conversely, standard (NON-Hemostatic) gauze should be left in, with additional dressings or bandages piled on top, if it doesn’t stop the bleeding right away.

High and Tight–A mnemonic (especially useful for Marines, who wear their hair that way) for where to place a tourniquet in TACTICAL situations. Most literature (see, for example the American College of Surgeons Stop the Bleed version 2.0) says to place a tourniquet “2 to 3 inches above the wound.” Which works OK in emergency rooms and well-stocked ambulances, since, if the vessel has retracted above where you place the tourniquet, or it is lacerated internally above where you place the tourniquet but the blood is exiting the limb below it, you can always place another of your 18 or 50 tourniquets above that when it doesn’t work. In the field, in a tactical situation where we may be hiding in a dark closet and unable to thoroughly examine the entire limb and when the subject may have several holes (say, from a load of buckshot) and we may be lucky to have even one tourniquet, IT MUST WORK THE FIRST TIME. So in tactical medicine, we put the tourniquet on High and Tight–as high up as we can possibly get it on the limb.

The higher on the limb that tourniquet is, the more tissue will be affected and the longer it will take the hospitalists to remove it safely. That’s not your problem in a tactical situation. Your job is to get that patient through the emergency room door alive. High and Tight is the best way to do that with the limited resources you have available in tactical situations.

For more, read “Where to Put It: Tourniquets and Other TacMed TTPs,” on pages 46 – 48 of the September 2024 electronic edition of The Blue Press.

HAINES (High Arm IN Endangered Spine)–using the arm of an unconscious person as a pillow to keep their cervical spine aligned when you roll them into the Recovery Position. See Cervical Spine Stabilization.

Hemothorax–blood in the chest cavity.

Hemo-pneumothorax--blood and air in the chest cavity, especially in the pleural space outside the lung.

Hypothermia–Lowering of the core body temperature. Hypothermia is the H of the MARCH algorithm due to something called Cushing’s Triad. The short version is, COLD BLOOD DOES NOT CLOT, and blood loss is the number one PREVENTABLE cause of death after injury. Keep trauma victims warm.

ICSAVE (Integrated Community Solutions to Active Violence Events)–A non-profit organization whose mission is to educate our communities about how to keep the body count low when active killers attack.

For more about ICSAVE, visit ICSAVE.org or read “ICSAVE: Saving Lives, One School at a Time” on pages 46 – 48 of the July 2024 electronic edition of The Blue Press.

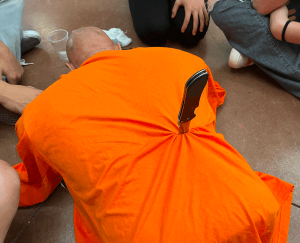

Impaled Object–Anything stuck in the wound. It could be a weapon, or they might have just fallen on a piece of rebar. Theoretically, the impaled object, and any clothing it pulled into the wound, might be Tamponading, or filling up, the hole it made going in. In other words, it might be “packing” the wound, so removing it could make things worse.

So as a general rule, we do not remove Impaled Objects in the field, if we can avoid it. Rather, we use Bulky Dressings (a doughnut or pyramid of material shoring up the object) to stabilize it in place for transport. If you don’t have any bulky dressings, you can cut the patient’s shirt and wad it up around the object, taping it in place to accomplish the same objective.

Remember,

“If you can’t do it with duct tape, you’re not using enough duct tape.”

–Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson

Although it is ALMOST never a good idea, there is no 11th Commandment from the Designer of our bodies that “Thou Shalt Not Remove an Impaled Object in the Field.” If an Impaled Object is blocking the airway, we absolutely must remove it ASAP. Also, if you cannot pack a severely bleeding wound because you keep cutting your fingers on the sharp Bowie knife that is impaled therein and causing more damage each time you try, by all means remove it.

Transport the victim with the affected side down, if possible. Gravity will pull blood and other fluids down, so keeping the affected side down means less compromise to the unaffected side. Also, if the Impaled Object broke any ribs on the way in, transporting the patient with the affected side down will help to splint the ribs against the back seat of your Ex-cab.

Improvised Chest Seal–A short term solution to a long term problem. If you do not have a purpose-built, VENTED chest seal, and IF it would not delay transport, you can temporarily stave off development of tension pneumothorax by applying an occlusive dressing (one that does not breathe, like Saran wrap or a plastic bag) over a penetrating wound of the chest.

To improvise a chest seal, TAPE THE DRESSING DOWN ON ALL 4 SIDES, COMPLETELY SEALING IT. We used to recommend only taping three sides, to create a “vented” improvised chest seal, but that never worked in well in practice as it did in theory. Completely hermetically sealing the hole(s) in the outside of the chest wall DOES NOT PREVENT AIR FROM ESCAPING INTO THE PLEURAL CAVITY through perforations in the lung itself. Accordingly, after applying an improvised chest seal, one should roll the patient on the affected side, and continuously monitor them for signs and symptoms of Tension Pneumothorax:

- Increasing respiratory difficulty

- Absent breath sounds on the affected side

- Bulging neck veins

- Tracheal deviation (Adam’s apple moving off to the side–a VERY late sign)

If any of those signs / symptoms are present, lift a corner of the tape holding your dressing in place and “burp” it, and have them breathe out again, before taping it back down. See also Field Expedient and Vented Chest Seal.

Indirect Threat Care (IDC)–In TECC, we use Indirect Threat Care protocols in the Warm zone. We place tourniquets if necessary and re-evaluate tourniquets that were placed, perhaps hastily, in the Hot zone. IDC protocols allow for better airway management than just rolling a downed patient into the Recovery Position. We might place a Nasal Pharangeal (NP) Airway, or sit patients with facial injuries or chest trauma up to help them breathe. In the Warm Zone, we collect and triage casualties, doing complete MARCH or BATH assessments. We prep the most urgent for evacuation, treat for shock as necessary, and fix the walking wounded well enough to help us protect the Casualty Collection Point(s) or to help us move casualties out to the Cold zone.

Inferior Vena Cava–The lower of the two venae cavae, the largest veins returning blood to the heart (colored blue in the diagram below). The Inferior Vena Cava runs up the back of your body, behind most of your other organs and whatever is hanging over your belt, whether you are pregnant or just look pregnant, like I do. It’s not a good idea to lay semi-conscious or unconscious people on their backs, to protect their airway and to keep weight off of their largest blood vessels. The Inferior Vena Cava runs up the abdomen to the right of their spine, so if the person has a lot of weight in their abdomen it’s a good idea to lay them on their left side to keep weight off of their Inferior Vena Cava (see Left Lateral Recumbent below). Arteries are pressurized and can push past that weight more easily than veins.

Inguinal Fold–the crease at the bend where the abdomen meets the front of the legs. The fold is over the inguinal ligaments running between the two pubic bones and the anterior superior iliac spines, those two bumps on your hips in front where the top of your pelvis takes a sharp downward turn (see diagram at Femoral Triangle).

For most of us except really cut body builders, the Inguinal Fold ends up looking like a V when we stand up, ending roughly at the top outer corners of the pubic region. The femoral arteries run across the pubic bones at the top ends of that V, creating an Arterial Pressure Point.

Junctional Area–a place where the limbs or neck meet the trunk of the body–the shoulders, buttocks, and hips. Because they are full of muscle, bone, and connective tissue, providing some internal structure to push against, Junctional Areas are where we pack wounds if possible (we can also pack limbs, but we prefer a tourniquet on limbs; Junctional Areas are too high up to be tourniqueted).

Junctional Tourniquet–One way to deal with a femoral Laceration that is just a little too high up to be tourniqueted. Junctional Tourniquets apply pressure where the femoral blood vessels cross the pubic bone, at about where the Inguinal Fold (the “Y” of the groin”) ends when most of us are standing. There are two types: purpose built and improvised.

Purpose-built Junctional Tourniquets are probably too bulky to carry in a personal first aid kit, but may be something you keep in the ambulance or trunk. They are expensive, complicated, and time consuming to apply.

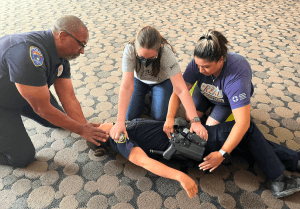

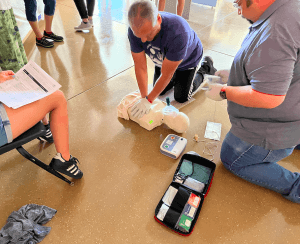

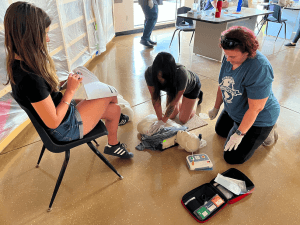

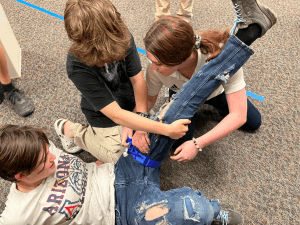

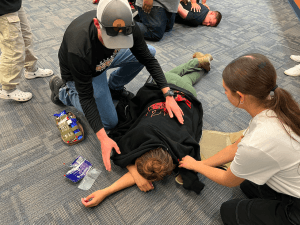

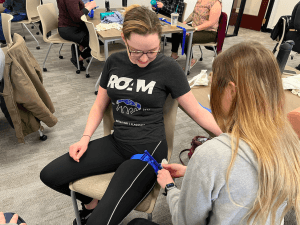

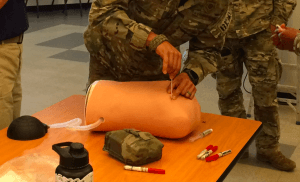

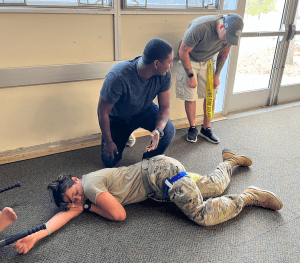

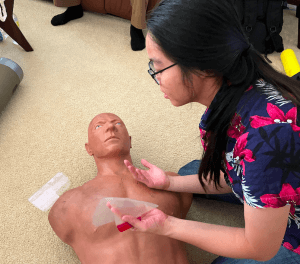

In this top photo, students apply a purpose-built Junctional Tourniquet. The light colored, trapezoidal blocks press down on the Inguinal Fold (the Y of the groin) where the femoral blood vessels cross front of the pelvic girdle, when they are screwed down using the T-handles.

Improvised Junctional Tourniquets are cheap, not quite as effective, not quite as complicated, and equally time consuming to apply.

With either kind (purpose-built or improvised), Direct Pressure should be applied (with a fist, forearm, or shin) to the Pressure Point(s) at the top of the Y on the affected side(s), till you are almost ready to tighten down the Junctional Tourniquet. It takes a long time to apply a junctional tourniquet, even if the rescuers are well and recently trained. It takes no time at all to drop your shin onto the Pressure Point, and accomplishes the same purpose almost as well, at least until it’s almost time to stick the casualty in a chopper. Given that most of us have limited space and even more limited budgets, you’d probably be better prepared for most contingencies if you invested the money you would spend to get a single Junctional on a whole bag of standard Tourniquets instead.

Laceration–a cut, as opposed to a poke (Penetrating Trauma) or a scrape (Abrasion). Like saying “Stat,” referring to a cut as a “Lac” (like “lack,” e.g., “He’s got defensive lacs on both forearms”) can make you sound medicool.

Lateral–the side, specifically of the body, but can be used to mean “to the side” in other contexts.

Left Lateral Recumbent–Fancy medical term for lying down (being recumbent) on the left lateral aspect, or side, of the body. When placing a very pregnant patient in the recovery position, we put them on their left side. If we put them on their right side, the weight of the baby would be pressing down on their inferior vena cava, restricting blood return to the heart.

Lima Carry–Named after an outstanding instructor, the BorSTAR medic who taught it to me, Lima “Carry” is the easiest and most tactically sound of all: having the patient crawl to you, rather than exposing yourself to enemy fire to lift and carry the patient. It should be noted that apart from other immediate members of my instructional circle, nobody else calls it the “Lima.”

Linguini Poisoning–allegorical term for the main cause of most heart attacks: too much food, too little exercise, over too much time.

MARCH Algorithm–A military mnemonic for prioritizing treatment of the injuries or maladies you find on a casualty in the field. When a patient has, say, a sucking chest wound, and a femoral bleed, MARCH tells us which one to treat first. In descending order of importance, the MARCH steps are:

- Massive Hemorrhage (bleeding). We treat major bleeds before any other injuries, because they can kill the patient before other injuries do.

- Airway (the passage from the nose and mouth to the lungs). The airway of an unconscious patient could simply be blocked by the position of their neck, or a foreign object lodged in the throat. If it’s a foreign object (big chunk of hot dog in a kid’s throat), that is an immediate threat to life that must be treated quickly. Abdominal Thrusts (formerly called the “Heimlich maneuver“) are the answer. If you have the time and the tactical situation permits, roll unconscious patients (especially those snoring or gurgling) into the Recovery Position. We must use the Head Tilt Chin Lift, or the Jaw Thrust, if performing CPR (see Respirations), but those methods tie up our hands, which may be needed to return fire in a Hot Zone.

- Respirations (breathing). Although Compressions Only CPR is actually more effective for the majority of situations when the heart has stopped (most of which are caused by Linguini Poisoning), there are situations (drowning, Opioid Overdose) where aggressive respiratory support is the key to success. In some situations (such as medically induced coma / paralysis for RSI, rapid sequence intubation), a patient’s heart may still be beating, but they are not breathing, in which case Artificial Respiration / Rescue Breaths are required. The Respirations phase of MARCH is where we treat Sucking Chest Wounds, usually with a Chest Seal, and / or (if you are qualified and equipped to do so), Needle Decompression. If they are breathing and you cannot find any penetrating trauma (holes in) chest, if nothing else, monitor the patient frequently to make sure they are STILL breathing. If they stop breathing, their heart stopping may have caused it. Even if the heart is still beating when they stop breathing, it will quit soon unless you get air in there. If the heart does stop, we move on to:

- Circulation–If there is no heartbeat nor signs of circulation, CPR, including rapid, forceful chest compressions, is necessary, UNLESS: you have other patients that you CAN save, or you cannot get a pulse because they are leaking out. If you squeeze a water balloon with pinholes in it, you only make the water run out faster. In a Mass Casualty Event, people who need CPR are generally ignored unless and until you have no other jobs for your rescuers, because your chances of a successful outcome for the patient are slim, and CPR takes time and resources away from other patients with life-threatening but fixable injuries.

- Hypothermia & Head Injuries–After you have treated all the above problems, wrap them up like a burrito and keep them warm, because COLD BLOOD DOES NOT CLOT. Head injuries require special consideration. We would not, for example, apply direct pressure to a skull fracture or penetrating injury of the brain.

Although many still use MARCH, the military is drifting toward the simpler BATH assessment.

Mass Casualty Incident (MCI)–Technically, any time there are more casualties than people with medical training to treat them, necessitating triage. If you are by yourself, and you have two patients, that technically constitutes an MCI. Active Violence Events are often MCIs; not all MCIs involve active violence, and not all Active Killer Events result in multiple casualties.

MCI–see Mass Casualty Incident above. Also can be an abbreviation for Multiple-Casualty Incident, which is essentially the same thing.

NAEMT–The National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians

Naloxone (Narcan)–A medicine that can reverse the effects of opioids. Naloxone can be administerd nasally (up the nose) by lay rescuers, and it works great if the person you are using it on is still breathing at least a little. It does not work as well on someone who has stopped breathing altogether. If they are not breathing, you can still administer Narcan, WHILE YOU ARE PERFORMING CPR WITH AN EMPHASIS ON VENTILLATIONS.

Neck Drag–a niche Patient Movement Technique for situations where being vertical can be hazardous to one’s health. An infantry CasEvac method, civilians find it most useful for dragging an unconscious casualty out of a housefire when neither is wearing SCBA (self-contained breathing apparatus). The Neck Drag allows you to keep your airways down below the carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, and other toxic byproducts in the smoke of a burning structure.

If the patient is conscious but can’t move their legs, they can just hang on to your neck like a petite cheerleader might when hugging a tall basketball player. If the casualty is unconscious, you will need to tie their wrists together with something and put their arms on like a necklace.

In the TacMed world, the Neck Drag is useful for staying behind low cover like a fallen log. It may also be useful for confined space rescue, say, from a culvert.

Needle Decompression–Officially known as “Needle Thoracostomy.” It’s a field expedient way of relieving EXISTING Tension Pneumothorax (to prevent or delay the onset of Tension Pneumothorax, use a Chest Seal, which is much less invasive and requires far less training). I reiterate that the skills discussed here are for educational purposes; do NOT attempt any of them without training, and in some cases (like Needle Decompression), certification by competent legally authorized medical authority.

Although it’s called needle decompression, it’s really catheterization (inserting a miniature straw); we only advance the needle till it punctures the inner chest wall; then we advance the catheter and withdraw the needle. We typically use a 5 cm long angiocatheter, although if you are sticking Dolly Parton on the mid-clavicular line (see below), you may need an 8 cm angiocath. Shorter needles may not do the job, but longer needles have a higher likelihood of injury. Selecting a better site and direction of insertion is safer for the patient than using a longer needle.

There are three places a trained provider can Needle D:

- Along the mid-clavicular line (a line running down their body from the middle of their Clavicle, or collar bone), between the 2nd and 3rd rib (their “second intercostal space”) or

- The anterior axillary line, which runs down their body from the front of their armpit, just behind their pectoral muscle, in the 4th or 5th intercostal space. This is my personal go-to for needle decompression.

- The mid-axillary line, which runs from the middle of the armpit, in the 4th or 5th intercostal space. Although studies have shown the Anterior Axillary line is most effective, some trainers only teach mid-axillary or mid-clavicular to keep it simple.

The axillary lines are generally preferred in TacMed for two reasons:

- Many humans are overfed, and chest wall thickness is more consistent under the armpit than under the collar bone.

- For practical / tactical reasons, our patient may still be wearing body armor. We can slide the needle past it through the Shooter’s Pocket, the gap in the armor under their arms.

You can find the second intercostal space by feeling the between their ribs, starting at the collar bone, but you may have to press really hard.

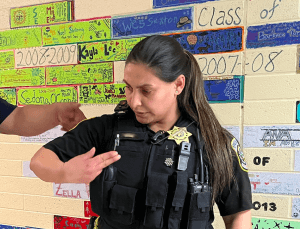

It’s faster to find the correct distance down under the armpit. Stick the PATIENT’s opposite-side hand (NOT yours) under their armpit, index finger side up. Their pinkie side will be at the 4th or 5th intercostal space, and either one will do. Note that in the photo above, my friend Ray’s hand is probably much larger than the officer’s, and hers is the one that will give us the correct distance down.

Regardless of which line you use, feel for the gap between the ribs, and slide the needle OVER THE TOP OF THE BOTTOM RIB. If you go to one of these modern restaurants or work spaces that does not have a false ceiling, you’ll see that power cables for the lights are slung under the roof support beams. Your ribs are the same way: each has and artery and nerves hanging from the bottom of it. Sliding the needle over the top of the rib below it keeps us from jabbing either of them.

One often overlooked but important nuance is the angle of insertion. With Axillary NDs, point the needle slightly upward, toward the opposite shoulder, which keeps us from puncturing abdominal organs such as the liver.

Needle Thoracostomy–see Needle Decompression above.

Occlusive Dressing–something waterproof, that we place over a wound to keep it from drying out, or, in the case of chest or neck wounds, to keep air from passing in and out.

We apply Occlusive Dressings, preferably purpose-built Vented Chest Seals, to any injury from the neck to the navel. This is because the Diaphragm flattens and stretches taut between our lower ribs when we breathe in. Occlusive Dressings can also be useful for keeping Abdominal Eviscerations moist, but do not adhere them directly to a protruding organ. Occlusive Dressings can also be useful with neck Lacerations.

Open Book Fracture–When the pelvic ring is broken in front, causing both sides of a supine patient’s hips to fall away from each other. The knees and toes end up pointing outward, like, well, opening the pages of a hardback book. The hip bones are like a doughnut that has been sliced on one side and pulled slightly apart till it is like a C; we need to make it into a O again. As a general rule with pelvic injuries, we slip a long wide bandage, such as a bed sheet, under their buttocks and wrap it around the hips, and cinch it together to approximate (bring together) the broken ends of the pelvis. There are commercial Pelvic Binders available, but from what I can tell they don’t do much that that Sterile Burn Sheet in your first aid kit can’t do.

Penetrating Trauma–Stabby / Pokey / Shooty type injuries. A stab is penetrating injury, but a slash is not. Unless they barely graze the patient, GSWs—Gunshot Wounds–create Penetrating Trauma.

Perfusion–When oxygen and nutrients are getting to the tissues, especially important tissues like the brain and heart. Lack of perfusion causes Shock.

Pericardial Tamponade–When blood leaks into the space between the outside of the heart and the inside of the Pericardium. The longer this goes on and the more blood that gets in there, the less your heart is able to fill with blood and function properly. The heart ends up getting squeezed literally to death. Pericardial Tamponade can occur from penetrating trauma to the heart (knife stab or gunshot wound), or from blunt trauma to the chest (steering wheel), from a ruptured aorta, or from medical causes.

Pericardium–The tough, fibrous sac that surrounds the heart.

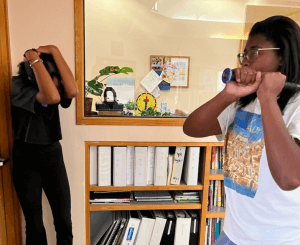

Physical Counterpressure Maneuvers (PCMs)–If you are feeling woozy at the sight of so much blood, you can do any of several different PCMs to drive blood up into your brain.

PCM options include:

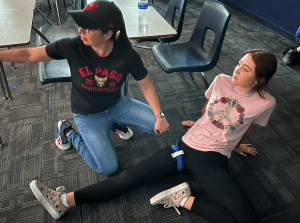

- Crossing ankles while tightening abdominal muscles (“abs”), glutes (buttocks), and leg muscles; this can be done lying down (preferable) or standing up

- Squatting while tightening abs as pictured above

- Clenching fists or squeezing a stress ball tightly

- Touching your chin to your chest and tightening the muscles in your neck

- Hooking fingers and pulling arms apart

Physical Trauma–see Trauma. As opposed to Psychological Trauma.

Pneumothorax–air in the chest cavity. See Sucking Chest Wound.

PCMs–see Physical Counterpressure Maneuvers

Positional Asphyxia–When a patient, especially an obese patient or one with a great deal of greater omentum (panza, or beer belly) lies face-down on their stomach (Prone), the tummy gets pushed flat against the surface they are lying on. This pushes the abdominal organs up under the diaphragm, reduces the ability of the bell-shaped diaphragm to flatten, and thus makes our breaths shallower. This reduces the oxygen to the heart, which slows the heart, in turn slowing breathing. and so on, in a degenerating death spiral. Combative, hog-tied suspects tossed on their bellies in the back of paddy wagons have been known to arrive at their local hospital or jail DOA. Positional Asphyxia is not a new discovery. We’ve known about it since the previous century. Positional Asphyxia likely contributed to the death of George Floyd, two decades into this century. The solution? Roll patients (and suspects) into the side-lying Recovery Position whenever possible.

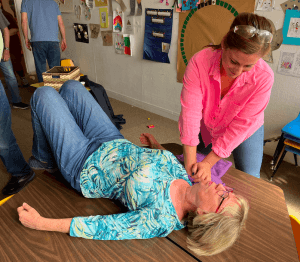

Even if her wounds were real, the Prone simulated patient in this photo from an ICSAVE Rescue Taskforce exercise would not be likely to suffer from Positional Asphyxia, because:

- Her tummy is flat to begin with. Positional Asphyxia mostly affects those with a larger “beer” belly.

- She’s not overdosing on drugs. In almost all cases of police “murdering” suspects through Positional Asphyxia, the patient has lethal or nearly lethal doses of recreational drugs already onboard.

Positional Asphyxia is a separate, complicating factor, or Comorbidity, that may be the “straw breaking the camel’s back,” tipping the patient over the edge. It is not likely to kill the patient in and of itself. If it was, I would have murdered many of my fellow Defensive Tactics Instructor candidates whom I cuffed on their bellies, over and over and over, in DTI school–or they would have murdered me, since I have a large enough belly to be in my second or third trimester of pregnancy.

Preparatory Command (as opposed to a Command of Execution)–Remember in Lethal Weapon II, when Riggs is getting ready to yank Murtaugh off the toilet, but a debate ensues: “Do we go on 3, or is it 1, 2, 3, GO?” When we’re hauling patients, we can’t afford to drop them because we got confused. And what are we supposed to do on 3, anyway? So instead, we use the military system, which is much harder to get wrong:

- A Preparatory Command, which tells everybody on the team what we’re going to do, and

- A Command of Execution, which tells everybody on the team when to do it.

For example, “Prepare to lift,” followed by “LIFT.” Or, “Prepare to lower, LOWER.”

Unless there is an established chain of command (senior medic on scene, or in a hospital setting where Doctor > Nurse Practitioner > Nurse > Paramedic > EMT > Med Tech) the rescuer nearest the head gives the commands. If there are two near the head, the one on the patient’s right (like the position of honor to the right of the head of a table), gives the commands. In this way we all know who’s in charge. The people near the head can see the patient’s face best. The patient’s face can tell us a lot about what’s going on with them.

Pressure Dressing–A Dressing attached to a wide Ace-type elastic Bandage, sometimes with an H-shaped or crescent-shaped plastic yoke for reversing direction of the Ace wrap to apply more pressure. Sometimes called a Combat Dressing, H-Bandage, or Israeli Bandage. In the short term, pressure dressings are unnecessary, as long as you have a spare human to apply pressure for you. However, in order to “package” a person with a profusely bleeding penetrating injury for evac, you will need to replace the person with a device that will continue to apply pressure to the injury during transport to a hospital.

Prone–Face down, on one’s belly. May be useful–or may not–when taking fire. Can sometimes lead to Positional Asphyxia, if other complicating factors (Comorbidities) are present. If a patient is in the open, and you ask them to crawl to your position of cover, they might do so while prone, or pushing themselves along on their side or back, depending upon the nature of their injuries.

Psychological Trauma–can be very real. Sadly, many people claim to have psychological trauma when what they really have is avoidance or inability to cope with the realities of adulting. Surely, having a friend bleed to death all over you is psychologically traumatic (the voice of personal experience speaks). Like physical scars, psychological scars generally get less painful with time and are not usually debilitating. According to psychologist, Army Ranger, and former West Point professor David Grossman, most combat vets have PTS, but only a small percentage have PTSD.

People who mean well, but know little of mental illness, want us to avoid “triggering” people at all costs, because triggers might make people feel bad–even though the medical literature on Anxiety Disorders states that the only way to overcome them is by at least controlled exposure to one’s triggers or stressors.

Too many people hide behind their “mentally scarring” experiences because mental illness has gone from being something shunned (which was bad) to something that is encouraged, lauded, and even, for many, a vocation. It became too much of a good thing.

Everybody has “a little crazy” in them. Most of us used to be pretty good about keeping it in check. Americans are no longer encouraged to keep their crazy in check. They are encouraged to act out, and rewarded for doing so, starting in elementary school. Then we are surprised when they shoot up a 4th of July parade.

We live in a world where people go on stabbing sprees malls, yet some people claim that discussing this aspect of our reality and perhaps even–gasp!–preparing to deal with it, is psychologically traumatizing in and of itself. I don’t know about all that, but I can tell you for a fact that FAILURE TO PREPARE FOR VIOLENCE IS FAR MORE PSYCHOLOGICALLY AND PHYSICALLY DAMAGING WHEN IT HAPPENS, than talking about it before hand.

Purpose Built–A tool designed and manufactured for the reasons you use it. Examples would be a fighting knife, as opposed to kitchen cutlery. You might grab a steak knife out of the butcher block on your counter if there is a home invader in your dining room, but it is more likely to break, and won’t make as wide a wound, as a Purpose Built fighting knife.

Another example would be a commercial tourniquet like the CAT or SOFT-T.

The opposite of Purpose Built is Field Expedient. You can improvise a tourniquet out of split pants legs and a tire iron, but by the time you find all the stuff you need and MacGyver it, your casualty may have already bled out. Purpose Built medical gear can be expensive, but it is almost invariably faster to apply and more effective.

I understand that the military is moving away from improvised tourniquets, and going to simply packing wounds in limbs when a tourniquet is not available: a Field Expedient, suitable substitute.

Recovery Position–A way to lay your patients so that they don’t choke on fluids in their airway. Unlike, say, the Head Tilt Chin Lift, it does not require you to remain hands-on with your patient, and frees you up to perform other tasks. In the Recovery Position, the person is lying on their side (“laterally recumbent“). Their down arm is extended up for them to rest their head on, like a pillow. This also keeps their cervical spine more or less straight (see HAINES, High Arm IN Endangered Spine). Their up leg is out in front with their knee down like a kick-stand on a bike. Their up arm can also be used like a kick stand, with their elbow on the ground (for slimmer patients) or their palm on the ground (for beefier patients). We do NOT want too much weight on their belly (see Positional Asphyxia). We want the face oriented slightly more down than up, but NOT face down on the ground.

Place UNCONSCIOUS, BREATHING patients in the Recovery Position, and then monitor them often to make sure they are still breathing. Time and circumstances permitting, you can roll a patient into the Recovery Position during the Care Under Fire phase of TCCC / TECC, or any subsequent / higher echelon care. OTHER INTERVENTIONS (BLEEDING CONTROL, CHEST SEALS TO THE FRONT OF THE TORSO) SHOULD BE PERFORMED BEFORE ROLLING THE PATIENT INTO THE RECOVERY POSITION. Raking the back to find less obvious wounds, or applying a chest seal to the back, is easier AFTER the patient is rolled into the recovery position.

Rescue Breaths–Also called Artificial Respiration. Using one’s own breath (about 14% O2), room air through a BVM (about 20+% O2), or a BVM with supplemental oxygen (up to 100% O2), to push air into a person’s lungs when their own ability to breathe has been compromised. Rescue Breaths are often, but not always, done in conjunction with CPR.

Rescue Taskforce (RTF)–A combined team (or teams) of medics (firefighters / EMS) escorted by law enforcement officers (LEOs) sent into the Warm Zones of Mass Casualty Incidents (MCIs), particularly Active Violence Incidents, while patients are still bleeding out, rather than after the entire scene is declared “Cold,” by which time the patients may have bled to death.

An RTF is NOT there to hunt for killers; that job belongs to a Contact Team (or teams). Instead, the RTF looks for victims, and treats the wounded they find.

Shock–means different things to different people. Often the word is used to describe when a person is hung up in the Orientation phase of the OODA cycle, during “shocking” situations. It also refers to receiving a sudden jolt of electricity travelling through part of the body, leaving an entrance and exit burn, and possibly stopping the heart. Medically, though, Shock is a lack of Perfusion–blood bringing oxygen and glucose–to the tissues, especially critical tissues like the brain.

SOFT-T (Special Operational Forces Tactical Tourniquet)–One of the more effective tourniquets available during the GWOT (Global War on Terror). The SOFT-T has a no-BS metal Windlass. The original SOFT-Ts had a narrow band that fed through a jaw-like clip. The clip was difficult to thread the squared-off, narrow end of the strap through, and would pop open (possibly killing the patient) if the back of the clip was bumped before the medic could tighten a screw that held it closed. The first problem was eased by cutting the end of the narrow strap at an angle, leaving it with a pointy end easier to poke through (like wetting the end of a thread and pinching it into a tiny point to run it through the eye of a needle).

Other complaints against the earlier SOFT-Ts were that the fabric of the band was somewhat flaccid, which made it difficult to put on one’s opposite arm one handed. It was especially difficult, with only one hand, to put the end of the windlass through into one of the triangle shaped rings that kept it from unwinding. Later generations solved this problem by using a C-shaped clip (licensed from the CAT people, I’m guessing) which is easier to lock the windlass into, if you only have one hand.

Later versions of the SOFT-T are sometimes called the SOFT-T Wide, since the entire strap is now wider than the “tail” of the strap on the earlier versions.

Sucking Chest Wound–Also known as Pneumothorax (see). A penetrating injury to the chest that goes through the chest wall into the Pleural Space. “Sucking” Chest Wounds may broadcast sucking or gurgling sounds. If a penetrating injury to the chest leaves a hole larger than a nickel, the path of least resistance to the Pleural Space will be through the hole in the chest or back, rather than through the mouth, nose and throat and eventually into the Alveoli, where the oxygen / carbon dioxide exchange with the blood is supposed take place. Left untreated, Pneumothorax can lead to deadly Tension Pneumothorax.

SWAT-T (Stretch, Wrap, and Tuck Tourniquet)–a glorified exercise band, but it works.

SWATs work better than most other tourniquets on small children and pets, although it must be said that with smaller children, direct pressure almost always works to control bleeding from a limb.

The SWAT-T is firefighter-proof. It’s almost special agent proof. The instructions are printed right on it. Make your first two wraps snug only. Then stretch it till the zipper marks printed on it look like checkerboard squares.

Keep stretching and wrapping the SWAT-T till the bleeding stops. Then wrap it snugly over a pair of your fingers. On the next wrap, tuck the end under the most recent wrap where your fingers were. Done.

Tactical Mechanical Tourniquet (TMT)–a tourniquet design that is somewhat of a cross between the SOF Wide and the CAT. Like a CAT, the TMT has a plastic windlass and Velcro. Unlike the CAT, the Velcro of the TMT is not an essential part of its function. Rather the Velcro of the TMT is just there to keep the loose or working end of the strap from flailing about after it is applied. Like later generations of the SOF, the TMT uses a cinching buckle and is very wide (wider is better with tourniquets; think stepping on a garden hose, rather than pinching it between your finger and thumb).

The TMT is easier to self-apply one handed than the SOF, though not, in my experience, as easy as one-handed self application of the CAT.

The signature characteristic of the TMT is its unique locking clip that keeps the windlass from unwinding under pressure. The locking clip is probably the part that takes the most hands-on training to figure out, although after you have worked with it a few times (from both directions of windlass rotation), the TMT clip is simple to use, if not completely intuitive.

Tamponade (noun)–See Pericardial Tamponade

Tamponade (verb)–to fill a void preventing or reducing blood loss from the void. Packing a Junctional Wound densely enough with gauze can Tamponade it. An Impaled Object wedged up against a lacerated vessel can Tamponade the wound, which is why we avoid removing Impaled Objects in the field, if we can.

TECC (Tactical Emergency Casualty Care)–Stateside, civilian counterpart to the TCCC protocols.

TCCC (Tactical Combat Casualty Care)–A set of medical protocols for patient care when taking, potentially taking, or having recently taken hostile fire. Designed for the military, various aspects of TCCC have been adopted (as TECC) for use in certain similar civilian combat equivalents, such as Active Violence Events.

Tension Pneumothorax–is a very dangerous, life threatening condition. When air enters the pleural space outside the lungs (Pneumothorax, or “Pneumo”), it can eventually crush the lungs and even the heart (Tension Pneumo). Signs and symptoms of Tension Pneumothorax include:

- Increasing respiratory difficulty

- Absent breath sounds on the affected side

- Bulging neck veins

- Tracheal deviation (a VERY late sign)

Tension Pneumo can be alleviated, at least temporarily, by Needle Decompression. Onset of Tension Pneumo can be delayed by applying a Chest Seal (or sealS, if there is both an entrance and an exit wound in the torso). It can be delayed longer or even prevented by early application of a Vented Chest Seal.

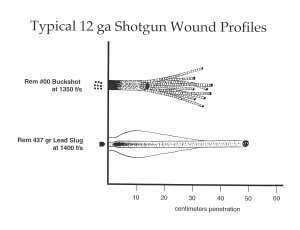

Terminal Ballistics–are what happens to the bullet after it hits a target (the intended target, or otherwise). If you have ever hunted large ungulates (big game) you may have some idea how unpredictable Terminal Ballistics can be, despite all the fancy ballistic gelatin tests and the fantastic claims of ammunition manufacturers.

Threat Actor–fancy term for a bad guy. A person (of any gender or orientation) who chooses to harm others, or threaten others with bodily harm.

TMT–see Tactical Mechanical Tourniquet

Tourniquet (TQ)–A band of material wrapped around a bleeding limb between the laceration and the heart, which, when tightened enough, keeps blood from leaking out of the wound. Usually, but not always, Tourniquets make use of a Windlass, a stick twisted to tighten the constricting band. Tourniquets are vastly misunderstood. Placement of a tourniquet does NOT mean the patient will lose the limb below where the tourniquet is. If a tourniquet is removed after it has been in place for some time, without taking certain precautions, the resultant flood of CO2 rich, oxygen starved, rhabdomyolysis clogged blood CAN kill the patient if they take the tourniquet off too fast. However, with proper treatment, Tourniquets can now be removed IN THE HOSPITAL quite safely. Unless you are in the wilderness or a full-scale military battle and cannot reasonably expect to get hospital-level care in the next 48 yours, NEVER LOOSEN A TOURNIQUET IN THE FIELD. Do NOT use a Tourniquet for minor bleeding, but if a limb is bleeding severely enough to be life-threatening, or if you’re not sure if it is or not, don’t hesitate to place a tourniquet.

The parts of the CAT, a typical tourniquet, in this photo are, from top to bottom:

- The Loose, or Working End / strap

- The Buckle

- The Windlass

- The C-shaped Windlass Clip, and

- The white Securing Band or Time Stamp. These come in different colors.

One tourniquet may not completely stop the bleeding, especially from a leg. If you have a second tourniquet and the bleeding has not stopped, put a second tourniquet adjacent to the other (the literature says “immediately above the first tourniquet, but if you are really high and tight, you won’t be able to place another tourniquet above it). It may help to offset the windlasses so the second does not get hung up on the first as you tighten it.

If you don’t have a second tourniquet and it is still bleeding, consider Wound Packing.

Trauma–Damage to part(s) of the body caused by force, rather than disease. When we talk about Trauma in Tactical Medicine, we’re usually talking about physical, rather than mental, damage (Psychological Trauma).

Transition to Police Control (of the Scene)–If you come across a downed law enforcer and it is relatively safe to do so, please render them any and all aid within your repertoire. Just be prepared to FREEZE and, if instructed, back away from your patient, at least temporarily, if and when it will keep you from getting shot by the responding good guys. All they will know at first is that you are leaning over a downed officer (or other victim of violence).

You must think about the end game in tactical medicine. Once you start treating a casualty, your attention will be tunneled in on them and you may be experiencing Auditory Exclusion. Even if you sense the uniforms approaching, you will not be inclined to stop treating your patient, until they are in an ambulance on their way to the nearest trauma center. Just remember that if you get shot and fall across your patient, bleeding into their airway, you haven’t done the patient any favors. Plan to pause long enough for the cops to sort the good guys from the bad. See also Wyatt Protocols.

Transport–evacuating a patient to a higher level of care. For injuries to the head or torso, the best treatment you can give your patient might be applying diesel or gasoline to the engine of your car, with them in the back. The pedal on the right makes it go faster. In EMS we have something we call The Golden Hour (see). Studies have found that gang-bangers injured in drive-by shootings (excuse me, I meant “members of ongoing criminal organizations who use vehicles to facilitate their homicides”) have a higher survival rate than innocent victims. This is because good guys, having nothing to hide, lay there on the pavement and bleed until the cops have cleared the scene, and then till the paramedics arrive and do all their magic. They may get to a hospital in 50 minutes or more. In contrast, the driver who sees that his or her gunner was hit by return fire during the drive-by races to the nearest hospital, boots their homey onto the curb outside the Emergency Room, honks the horn, and drives away. The wounded gang member ends up under hot lights and cold steel in a surgical suite 20 minutes after the injury. Transport in an ambulance is usually preferable but if you are in a rural area and no helicopters are available, you may be able to cut transport times by meeting the ambulance halfway.

Transport is sometimes called CasEvac (pronounced “CAZ-evac,” for casualty evacuation to a higher echelon of care) in the military.

Triage–Sorting. Especially, sorting in order of priority. In tactical medicine, triage is dividing patients into the following groups:

- Those who can be patched up enough to return to the fight ASAP

- Those who need evacuation to a higher level of care

- Those whose poor likelihood of survival does not warrant the time you will be spending away from the 1s and 2s trying to save the 3s.

When evacuation from the area becomes possible, the 2s are broken down further into two groups:

- Those in need of immediate care (such as surgery), and

- Those (with, say, broken arm bones) for whom a hospital visit will eventually be necessary, but are less likely to die if they are not evacuated right this second.

Tunneling or Tunnel Vision–Part of the Fight or Flight Reaction. Medics are particularly susceptible to tunneling in on their patient, and missing not just sights but sounds and other stimuli in their environment outside patient, who becomes their entire world for the duration of the life-threatening emergency. See Ways to Fight Tunneling In.

Vena Cava–singular form of the plural venae cavae (see below).

Venae Cavae (plural of vena cava)–the two largest veins in the body, which return deoxygenated blood directly into the heart (specifically, into the right atrium). Veins are like rivers that grow larger as they are fed by tributaries (smaller veins and venules). The mouths of the two largest venous “rivers” in our bodies flow into the “ocean” of the heart. The superior vena cava brings blood from the north (the head, arms, and upper body); the inferior vena cava brings blood collected from the south, or legs and lower 2/3 of the body.