Hypothermia: Lessons from SERE

I live and do most of my teaching in Arizona. Most of our environmental emergencies are from heat, not cold.

And yet you may be surprised to learn that, paradoxically, Arizona has a higher number of cold related emergencies and deaths compared to other states. One of Arizona’s home-grown American heroes, Ira Hayes, died of hypothermia between Phoenix and Tucson–not a region of the world known for its cold temperatures.

A few reasons why Arizona has such a high rate of hypothermia:

- People who camp or hike in AZ often go to higher Alpine elevations to beat the heat.

- People in colder states prepare for the cold with blankets and candles and extra jackets in their cars; “Zonis” don’t take cold as seriously.

- It does NOT need to be freezing for you to die of hypothermia

Hypothermia 101: Effects and Treatment

HypOthermia, lowering of the core body temperature (as opposed to hypERthermia, too much body temperature) occurs in several stages. As with shock, the first stages are compensatory (meaning, your body is adjusting to compensate); later stages are decompensated (your body can’t keep up with external factors) and if untreated will lead to disability or death.

The first stage is goose bumps and shivering, perhaps with rapid jaw movement leading to “teeth chattering.” Goose bumps are hair follicles standing on end to slow the airflow around your body. Shivering and teeth chattering are your body’s ways of burning calories through exercise, even if you’re sitting still.

Which leads us to our first treatment method: DO NOT SIT STILL. Have your patient get up and walk around, as long as it is not exposing them to the elements (like rain and wind) more. Do NOT let them fall asleep.

As the core temperature drops further and the body loses the battle to stay warm inside, the heart rate slows. The person becomes confused and may do stupid things (like leaving shelter). Eventually they lose consciousness and die.

Treatment for mild hypothermia is to dress warmer or get out of the elements. If hypothermia is severe–you were planning to ice fish but fell through the ice, miles from your car–you need to be more aggressive in your treatment. You CAN survive falling through the ice (I’ve done it lots of times, actually, when I was in Wyoming) but you need to keep moving.

First, seek shelter from the wind / rain / snow. You can build a lean-to type shelter with a blanket or poncho, a few sticks, and 550 (parachute) cord. A cabin with a stove or fire or heater is better.

Strip off any wet clothing (this is no time to be shy, or overly concerned about modesty), dry the patient off with a towel if possible, and then immediately bundle them up in warm dry clothing. Most of your heat is lost though your head and feet, so make sure both are covered if you can.

The first aid manuals say to apply heat packs to their neck, armpits, and groin, where the blood vessels are closest to the surface. Which is swell–IF you have heat packs.

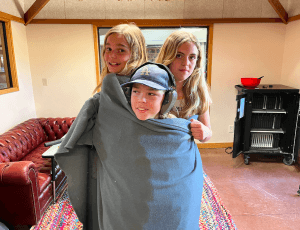

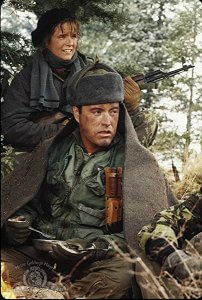

If no fire, heat packs, or other artificial warmth is available, remember that you and your friends are 98.6 degree warming units. Cuddle up under a blanket–or several blankets–with the patient, regardless of their gender / orientation or yours. This isn’t about romance (or lack of romance); it’s about saving their life.

If the person has frostbite, be gentle with their frozen parts. Wrap frozen fingers or toes separately and loosely with dry gauze. Gradually re-warm the person.

Remember also that severe hypothermia can make the person seem dead. They’re not dead till they’re WARM and dead.

SERE

Survival training at the Air Force Academy has gone through several modernizations since I was a cadet there in the early 1980s. In those days, during the peak of the Cold War, most of our planning revolved around repelling a Soviet invasion of Western Europe. It was estimated that within three days of any such war starting, at least half of our pilots were going to be shot down on the other side of the FEBA (the Forward Edge of the Battle Area), either dead, captured, or evading capture.

We were told to NOT expect rescue if we were downed in a European war with the Russkies.

The conventional war scenario in Western Europe revolves around Warsaw Pact armored formations. Outnumbered and outgunned on the ground, NATO must stem a communist advance with tactical airpower: airplanes and helos equipped to kill tanks. In the midst of a continuing battle for general air superiority, tactical aircraft will fight at low level, drawn to battle by the approach of enemy armor. Toss in mobile flak and SAM batteries, plus shoulder-mounted antiaircraft weapons, and you’re in for a real slugfest: high intensity, short duration, extremely lethal.

–A Barrett Tillman quote I wrote down in 1984

USAFA cadets were almost all slated to be pilots.

After the arduous, fourth class (freshmen, or “Doolie”) year, there was one more hurdle we called “the last fourth class haze:” SERE school. For almost all USAFA cadets, Survival, Evasion, Resistance, & Escape school took place during the summer between their fourth class and third class (sophomore) years.

I like to camp, but I also love to eat. Most of us (including me) dreaded having to go through SERE, especially the Resistance phase. But SERE was, in retrospect, some of the very best training I ever got in my 34 year military career. Mainly becasue it was the first time in my young, privileged life I’d ever gone for more than a few waking hours without stuffing something in my face.

The vast majority of Americans, even relatively poor ones, never know hunger (as Bill Maher pointed out, “Even our poor people are fat”). There are too many homeless and truly poor people who experience hunger daily, but the majority of us can’t honestly empathize with them because we don’t know what it’s like. The “Trek” (Survival & Evasion) phase of SERE we went for days without a square meal. We were watered, but not fed, during our days in the “Resistance & Escape” phase, a simulated PoW (Prisoner of War) camp.

Other branches of the military had their own versions of SERE, but the Air Force Academy’s was the only one I was aware of that was part of a service academy curriculum in those days. We got cadets from West Point (the US Military Academy) and midshipmen from Annapolis (the US Naval Academy) who chose to spend part of their upper class (junior and senior) summers with us, taking SERE, just as I later chose to spend the summer of my junior year at US Army RECONDO school. The military academies encourage such “cross-pollination” with our sister services, in preparation for joint duty assignments and combined-arms operations, which are just fancy words for supporting each other and working together as a team.

When I went through SERE, we did our Trek training (Survival and Evasion phases) at Saylor Park, in the Front Range of the Rockies north of Pike’s Peak in Colorado. The first four days or so of our Trek it was cool, and sometimes misty or rainy. The second half of the Trek, it was much colder. It just rained on us constantly.

I wound up on a great Trek team (I was probably the “weakest link”). Although Air Force Academy cadets were 90% male in those days, 50% of the six people on my Trek team were female, as was our Trek team’s instructor. Occasionally, some of us disagreed–we were all “hangry”–but I came to love each of those cadets like a brother or a sister.

My feelings for one of them, whose name was Shelly, were more romantically inclined than the agape-type affection one feels toward a beloved sibling.

Getting it Wrong–in a Simulation

Shelly woke up one morning shivering, with her teeth chattering.

Which was not out of the ordinary.

It was over 9,000 feet up there, and even in early June when it was not raining, we all were bitterly cold in the wee hours of the morning.

Our instructor thought this would be a good “teachable moment,” so she secretly ordered Shelly to pretend to be lethargic (sleepy) and confused–signs of more serous hypothermia.

At this point in the story it’s important to note that, difficult as it may be to grasp in this modern age, same-gender relationships were forbidden in the military in 1982. Not only forbidden; they were literally against the law, the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Furthermore, women had only recently been admitted to service academies. The first class with female cadets had graduated only two years before. The Air Force Academy had very strict rules prohibiting even the appearance of sexual harassment. It still happened, but as a general rule, cadet codes of behavior were vastly more restrictive than those of ordinary college students their age.

So there we were . . . 9000+ feet up in the aspen and pines and everything was cold and wet. Somebody yelled that Shelly wasn’t waking up, and we gathered ’round. We were unable to rouse her. I should have realized that it wasn’t the real deal because our instructor, who was responsible for our safety, didn’t jump in there to save her. But I had quite an adolescent crush on Shelly; my attention might’ve been “tunneled in” on her a bit too much. In addition to being an All-American track athlete, Shelly was a great actor–she had me fooled, at least. She didn’t just play dead; she mumbled a little and acted confused.

We had different ways of starting fires–flint and steel, matches, Bic lighters–but nothing worked. We tried to light a fire near her by every means we had, but it was so wet, every step on the moss or pine needles squished out great gobs of water. All the wood and kindling was soaked through. We couldn’t have lit a fire with a napalm strike.

We all knew what needed to be done. Somebody should have jumped into the sleeping bag with Shelly, to warm her up.

But nobody wanted to.

That’s not true. I really wanted to snuggle up next to her. I’m pretty sure that the other two guys on the team wanted to, as well.

But the guys were all afraid to. We didn’t want to get in trouble, possibly kicked out, for sexual harassment.

Had Shelly been the only woman there, maybe one of us might have jumped in there with her (I’d have certainly volunteered for such a sacrifice). But since there were two other women on our Trek team (plus a female instructor), the guys felt it might be more appropriate for one of the ladies to slide in with her.

The females, on the other hand, were reluctant to jump in there with her, because they did not want to indicate even the possibility that they might be “into” other women. Again, homosexuality was strictly forbidden in the military.

The worst part was that we were afraid to bring it up. We were teenagers, though we were legally adults. We’d all been through the classroom portions of Survival school; we all knew what needed to be done. But we didn’t even mention one of us jumping in with her while we were discussing our options. It was the “elephant in the room” that everybody knew was there, but nobody wanted to talk about.

So we knelt there, vainly trying to light a fire till our instructor, in disgust, finally threw her bush hat on the ground, screaming “She’s dead, you idiots! Because of you!” Shelly suddenly got much better. That’s when we realized it had been a simulation, rather than the real thing–and thank God for that; I think we really would have killed her through our reluctance to share body heat. There may have been some pushups or “dead bugs” involved, to drive the instructor’s point home.

The lesson here:

Don’t be bashful if you need to use your own body heat to warm somebody up.

It can be done platonically. I found that out a few days later, during the “Evasion” phase of our Trek.

Getting it Right–Out of Necessity

After the Survival portion of our Trek, our group broke up into two 3-person Evasion teams. A smaller team is easier to hide. The boys were on one Evasion team (mine), the girls on the other.

During the Evasion phase of the Trek, the main goal was to not get caught.

We also had to cover X number of miles per day, to make it to certain “checkpoints.” A person who is really shot down might have to get to an area where the anti-aircraft threat is not so high, in order to be picked up by a helicopter. Obviously, the threat was high wherever they got shot down, which is why they had to “hit the silk” in the first place.

If you were being aided by a partisan network, as the 8th Air Force airmen shot down over Nazi-occupied France often were (think of Powers Boothe’s Eagle Driver character linking up with teenaged guerrillas in Red Dawn), those who did not make it to their checkpoints on time might be assumed to have been captured, tortured for information, and replaced with impostors. You could be shot on sight for being late. So we had to do some distance.

At the same time, you had to be careful not to get caught. There were roving patrols of SERE cadre combing Saylor park to find us. The Air Force called such Opposing Forces (OpFor) role players “aggressors.” If they caught you, bad things would happen (probably including more pushups and dead bugs).

Whit, one member of our three-person team, just wanted to get to the next checkpoint via the shortest route possible, as soon as possible. The sooner we got to our final checkpoint of the day, the sooner we could build our evasion shelters (essentially a sleeping bag camouflaged under a pile of sticks, pine needles, and scrub that was supposed to look “natural”), and get some rest. We were burning calories at a prodigious rate, covering miles, up ridges and down canyons and over creeks, and trying to keep warm. But we were taking in hardly any. At least if you were horizontal under a pile of twigs you were burning less of your precious remaining body fat.

I, on the other hand, was obsessed with evading the aggressor cadre. I insisted on traveling “nap of the earth,” sticking to what we called the military crest, about 3/4 of the way up the side of a ridge or canyon (but not on top, where you might be silhouetted against the skyline). I wanted to crawl, rather than crouch, when we had to cross over the top of terrain features.

There had to be a healthy balance. My way was too slow; Whit’s was too fast. Dale, who grew up in Missouri, shot on the USAFA rifle team, and was easily the most competent woodsman among us, tried his best to speed me up and to slow Whit down. He also played peacemaker between us. After six days or so of starvation rations, Whit and I got on each other’s frayed nerves a lot.

Our last night in Saylor Park, we were in our evasion shelters when mine sprung a leak. Summer weather in the Front Range of the Rockies and the western plains frequently has “widely scattered afternoon and evening thundershowers,” but a wet weather system had parked over us for days, and stayed there. I could feel the wet spot growing in my sleeping bag. We’d done a good job of keeping them dry in water-resistant carry bags before that. I felt like the commander of a sinking submarine.

Whit’s sleeping bag was also getting soaked. The “fart sacks” were the old kind, made out of cotton canvas and goose down, not the modern magic synthetic sleeping bags you can bury in a snow drift and still keep warm.

I made a command decision (even though I wasn’t in command) and started building us a rain shelter with the small remaining section (the tip of two “gores”) of parachute I still had on me. Almost all of our gear had started out as a parachute, its harness, or in an aircrew survival kit. Whit and I were both really wet, really cold, and getting hypothermic. Our ACTUAL survival was now at stake, rather than our simulated survival. I no longer cared if the aggressors in the SERE cadre saw my pitiful little A-frame shelter or not. I figured any of them with any sense would be riding out the weather in their own shelters or heated vehicles, anyway.

Dale (not to be confused with Dell) offered to help Whit and me, but we told Dale to stay dry in his sleeping bag in case we got really bad and he had to go for help. No cell phones (and no cell phone GPS) in those days. No Gore-tex, either. We had wet cotton field jackets, wet wool socks, wet fatigues, wet wool caps, wet underwear. The suck wasn’t nearly as bad as those GIs in the Battle of the Bulge had it, but it sucked plenty bad enough for me at the time.

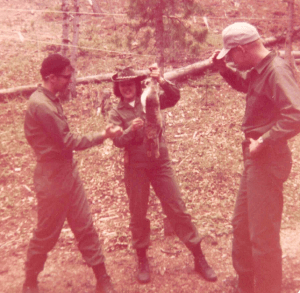

Whit was telling no one in particular that the cold was making his hands hurt. I told Whit to hold the angle-head flashlight where I could see where I was stringing 550 (parachute) cord between two trees and cutting it with “Roland,” my survival knife. I hung the tip of the teepee-like A-frame of parachute nylon from the string between the two trees. They issued us folding knives, but I had cheated and brought a Gerber Mark II, which was razor-sharp and really held an edge.

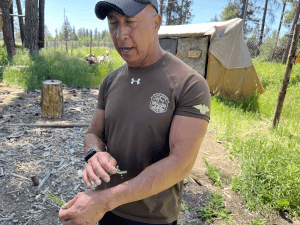

Roland was named more for Warren Zevon’s “Headless Thompson Gunner” than after the Frankish lord of the Breton March . . . and perhaps a little for Dr. Hook’s “Roland the Roadie,” whose luck with the ladies was almost as bad as mine back in those days. Other versions of the Gerber lacked the serrations on the back half of the blade. I found the serrations to be indispensable during SERE, especially for cutting parachute, which is–by design–very tough to rip or cut. Therese was using Roland to field-dress the rabbit in the photo closer to the top of this article.

The small, slab-sided folding knives they issued us in SERE didn’t even have locking blades. Bear and cougar attacks were exceedingly rare, but not unheard of in the Rockies, and both species lived in Saylor Park. I thought Roland’s blade might be long enough to get into a big cat’s vitals, in the unlikely event I or one of my comrades was ever caught in a set of giant feline jaws and getting shredded by claws. In retrospect, it might even have been worth the risk to be attacked by a large predator–we all could’ve eaten our fill, if we lived through it! But that night, we were far more concerned about not freezing to death than we were about the gnawing pits in our stomachs, which we were almost used to by then.

Our rain shelter, such as it was, consisted of two narrow triangles of silky nylon fabric, each little more than a foot and a half wide at the base, and about 3 to 4 feet tall, adjoined together on the long side. The planes of each triangle were about 60 degrees off from one another, so it formed 2/3 of a narrow triangular pyramid. I built it over a small section of water-soaked log, barely long enough for two starving, skinny post-adolescents to sit on side-by-side.

It was open on one side, and not really wide enough for both of our torsos and two arms apiece. In order to fit in, we had to wrap our closest arms around the other guy’s back. We squatted on the wet log, shivering, with our soggy socks in boots hanging out of the shelter in the rain.

We had no prayer of starting a proper fire (add two more days of rain to the water-logged forest since the adventure with Shelly above). My Bic lighter still had some juice, though, so I held it close to our faces and sparked it up. Whit cupped his free hand around it (and mine) as I held down the lever with my trembling thumb. When our faces, which were side by side, warmed up a bit, I would doze off from exhaustion (and / or from hypothermia), sometimes singeing one of my eyebrows, which would wake me up. Then I’d have to spark it up again.

To this day the distinct smells of wet canvas, wet nylon, wet wool, or burnt hair take me back to that miserable night.

The lighter didn’t contribute much to our overall store of caloric content, but we clung to it like a pair of rats to a floating plank from a shipwreck. After a while, the meager warmth of our nearly conjoined bodies made us slightly less miserable–or maybe we were just getting numb.

We didn’t like each other much at the time. But we were arm-in-arm, keeping each other alive.

After spending what must’ve been hours like that, Whit said, “You know, we should go out for a beer after this.”

–George H, Lead Instructor, Heloderma Medical

The first part of this post was excerpted from the training summary for a Heloderm Pediatric First Aid, CPR & AED class.