Ways to Fight Tunneling In

I’ve always lived most of my life in a mild fog, and it’s only gotten worse as I’ve aged. I’m easily distracted by the beauty in the world around us.

I was not in Naval Special Warfare, and I have not been in many battles. But based on my limited experience, the only plus side of being on the two-way rifle range was, it brought a clarity of focus that had not otherwise existed in my day-to-day world.

The Color of a Deputy’s Sleeves

Once, when asked who had been doing compressions while I was giving breaths during CPR, I said I wasn’t sure. “I know it was a deputy, but I couldn’t tell you which one.”

When asked how I could say with certainty that the compressor was a deputy, when I couldn’t even pick him out of a lineup, I replied that “He had the right colored sleeves from the elbows down. That’s all I saw of him.”

I had been so focused on my friend, the downed agent, that I did not even see those nearby who were not within the bubble of her chest and airway.

This intense focus on what matters most to us at the time, to the extent that we don’t even perceive things of lesser importance, is sometimes called “tunnel vision.” It’s a very common response to life threatening conditions.

The problem is not with our actual vision. It lies in our masterfully designed survival mechanisms, honed through millennia of surviving lethal situations. In the “Fight or Flight” reaction, the synapses in our brains fire faster to process information more quickly. We may perceive this as time slowing down. Of course, time clicks along as it always has, but we are processing stimuli faster, so everything that happens at its usual speed seems to be happening slower.

Our mind also filters out sensory data–sights, sounds, smells–it deems as unimportant at the time. The eyes are still transmitting everything, but the subconscious brain is trying to help us out, by only giving our conscious brain the images it thinks we need to see–usually those things (and only those things) we are looking directly at.

Once as I was locking a front door behind me, I heard a buzzing noise and turned to find an S-coiled, angry rattlesnake on my porch, ready to launch off the short wall it had backed itself against. Denzel Washington could have been standing on my front walk, and I would not have seen him. That rattler had my undivided attention.

When we respond to a medical emergency, we tend to “tunnel in” and go directly to the first patient we see. This can lead to a number of problems, especially in Mass Casualty Incidents (MCIs) caused by Active Violence.

Most importantly, it can cause us to miss hazards, especially those which created the MCI in the first place, which can make us become casualties ourselves.

At an MCI, tunneling in on the first patient(s) we see can cause us to tragically miss patients we don’t see, who may need our help more. A classic example is a vehicle rollover where several unrestrained passengers are ejected and one of them–often a smaller child–winds up in a ditch or behind some bushes. You can’t help someone if you don’t even know they are there.

Once you are actually working on a patient, that patient will be your entire world. Your “radar” will switch from wide-scan to narrow-beam, and your attention will be laser focused on life threatening injuries you find. Which is well and good, except that:

- You may be the best (or only) medically trained person on the scene, and other patients may have a greater need of your skills

- Without anyone watching your “6 o’clock,” it leaves you susceptible to attack should the author of the MCI return to complete his or her handiwork

Here are a few steps that can keep you and your patients alive:

- Look before you leap

- Take your time

- Use your neck

- The Antelope principle

- Delegate whenever possible, to stay global

I: Look Before You Leap

“Scene safe? BSI”

I was an EMT for roughly three decades. Every time we recertified on physical skills, we started our checklist with the mantra “Scene safe? BSI.”

The proctor, or whoever was checking us off on that skills station, would reply that the scene was in fact safe, and mark down on our checklist that before walking into a medical emergency we had at least checked the scene for hazards such as downed power lines, leaking HazMat, crazed killers brandishing machetes, or whatever else might have made our patients go from vertical to horizontal in the first place.

We said it because it was a critical item on the checklist. Sometimes, we actually looked around the room as we said it, as if scanning for hazards, but most of the time we just said it and moved on. We were just going through the motions–actually, not even that. We were just saying it out of habit, without connecting that verbiage to any physical activity, real or imagined.

Any professional who’s “felt a little heat” can tell you, life-saving skills are best learned hands-on, through training, rather than “education.”

Never did the proctor say “There’s a downed power line across the vehicle that hit the pole. Whatchu gonna do about it?” That would have taken time, and time is the training resource that is always in shortest supply. People recertifying want to check some boxes and go home. Which is one of several reasons why

“Qualification is not training, and training is not qualification.”

In other words, we talked about checking the scene before we launched into it, but other than waiting for the proctor to check us off before approaching the simulated patient in that particular skills station, we didn’t really practice it.

II: Take your time

Don Your PPE

The “BSI” of “Scene safe? BSI” meant we had taken basic Body Substance Isolation (also called “Universal”) precautions, such as gloves, masks, and / or eye shields, to protect ourselves from any number of diseases (we jokingly referred to them as “gono-syphi-herpe-litis”) the patient might be spewing into the environment.

We rarely had to actually wear eye pro, masks, or even gloves during our skills testing.

Pausing to put on (“don”) gloves and eye pro also gives us a moment to look around for things we might miss rushing in there too fast. Or, as the crusty older paramedics used to tell us FNGs, “Check your own pulse before checking the patient’s.”

But the Pappa bull says “No, son, let’s walk down . . .”

–Robert Duvall as LAPD CRASH Officer “Uncle Bob Hodges,” in Colors

Firefighters and EMTs walk, rather than run, into potentially hazardous scenes. A main reason for this is to reduce the chance that they’ll miss anything on the way in.

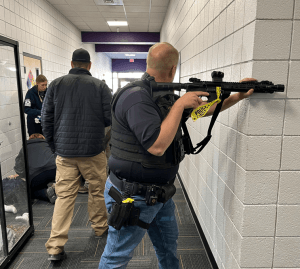

If you are responding to a shooting, say, as a member of an ad-hoc rescue taskforce, you may need to move fast across open areas, but never outrun the guns that are supporting you (see Movement to Contact for details).

III: Use Your Neck

If you haven’t read “Dealing with PESTS,” by Randy Harris, you should. FAST, the third chapter of Harris’ PESTS EAT FAST trilogy, stands for:

- Fight

- Assess (Is he Down? Is He staying down?)

- Scan left, right, and behind you (Does he have any friends trying to flank me?)

- The T stands for the Wyatt protocols, which start with T (for example, Top-off your weapons system; see TacMed Terms for a more complete listing of Ts)

After a shooting, it’s a good idea to scan the area around you for additional threats. More than half the time, a bad guy has friends. After we put him down, and we’re sure he’s staying down, at least for the time being, we “put our head on a swivel” to tear our focus away from him.

This can help break you out of your tunnel vision in medical situations as well.

The theory is, if you are focused only on that which is in front of your eyes, to the extent that your eyes don’t even swivel around in their sockets, you can fight that by moving the face your eyes are in to point in different directions.

But when training yourself to do this, beware of the Front Sight shake.

Most firearms training exercises used to end the moment the last shot broke. About 20 years ago, knowing it’s better to practice what happens after a shooting as well, advanced shooting schools started having students look left and right after each shooting string. But the obligatory “scan” can lead to a somewhat amusing phenomenon we used to call the “Front Sight head shake” (Front Sight was a training center SW of Las Vegas, Nevada, that is now under new management). Students rushed through the steps after each drill, including turning their heads left and right rapidly, without even looking at, much less seeing, anything to their left or right.

Be Holmes, rather than Watson

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s iconic investigator used to complain that his wingman Watson “looked, but did not see.”

One way to fight the Front Sight shake, and instead to actually perceive clues about danger (or additional casualties at an MCI) is to mindfully, intentionally practice it beforehand.

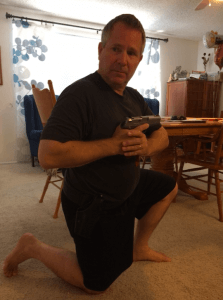

When I dry practice, I go through a series of AST / Wyatt Protocol steps after each drill. When I scan for additional threats, I turn my head to one side, looking for, in this order,

- People

- Open doors & thresholds to hallways

- Dead space

- Closed doors

These are all things that (in a real lethal force situation) might kill you if overlooked. Their likelihood of killing you is in descending order of importance. If you just got into a shooting, a person standing off to your right or left should be examined first for IFF (Identification: Friend or Foe?), since he might be a partner of the guy who just tried to kill you, and therefore is a greater threat to your safety than whoever may or may not be behind a closed door.

If that person is your partner, or a bystander, you need to communicate with them about what to do next.

When practicing scanning, I might say to myself, “There’s my wife reading a book; not a threat. There’s the hallway. I can’t see behind the kitchen island. The back door is closed.” It helps me to not just look at, but to actually perceive, my environment, identifying or disregarding potential threat areas in the proper order.

But it gets redundant after a while, since I only dry practice in a few specific areas, pointing my gun in a safe direction that will stop an errant bullet (there shouldn’t be any ammo in the gun, but if shouldn’t always meant wouldn’t, teen pregnancies would never happen). Other than my son possibly raiding the refrigerator, the view to my right is the same every time. To keep it fresh, and to keep my mind consciously engaged (rather than just going through the motions), to SEE, rather than just looking, the last thing I do each time is to identify AND NAME a different object. The first time I look to my left, that object might be “Vase on the piano.” The second time, it might be “Blue chair in the corner.” And so on.

This exercise can be time consuming, but it really helps improve your awareness of your environment. You do not need to do it in conjunction with dry practice. Set up the timer on your phone to alert you after X number of minutes (say, 18, or 36, or an hour and a half, or whatever). When it beeps, stop and look around, naming each of those threat areas and a random object to each side.

Unfortunately, our necks only turn so far. We might need to turn our bodies to see 360 degrees around us.

Search Systematically

So you didn’t see any other casualties strewn around the wreck when you turned your neck. If the one(s) you have found are getting care, or you haven’t found the victim yet, consider a roving, systematic search. You could walk in an expanding spiral around the accident site till you find the driver in the ditch. Ask anybody who might know how many people had been in that car.

IV: The Antelope Principle

When I guarded a nuclear weapons storage area (WSA), a SRT (security response team) would patrol the area outside the WSA. SRT was the most exciting security gig in the whole response force. You got to watch grass grow. And look at the antelope. There were two or three herds of pronghorn antelope grazing around the outside of our WSA at any given time.

“Did you ever notice,” my partner (I think it was Ken Tharman) asked me one day, “that whenever antelope bed down, at least one is always looking the other way?”

I looked at the nearest herd, and sure enough–one was facing the opposite direction of the others.

“That’s probably just a fluke,” said I.

“I s__t you not,” he continued. “I’ve been looking at them for years. Every single time I’ve seem ’em bedded down, at least one’s always looking the other way. Prove me wrong.”

I tried, over the next several years of living in Wyoming, where there are more pronghorn than they know what to do with. He was right.

My father was a fighter pilot. When fighter jocks write to each other, they might close their correspondence with a check mark, followed by the number six (like this: √ 6). The six was shorthand for “your six o’clock” (the nose of the aircraft points to 12). The phrase “Check six” meant “Take care, my friend, and watch out for what’s behind you.”

My dad flew Phantoms, twin seat fighters, in Southeast Asia. He had a “GIB,” “Guy in Back,” to watch his six.

You need your own GIB.

Before you get tunneled in on a patient, ask a bystander to watch out behind you. This is easier said than done. The drama is happening where you are working on the patient. Even professionals find that very distracting.

V: Delegate – Delegate – Delegate!

Better yet, don’t get hands-on at all, if you can avoid it.

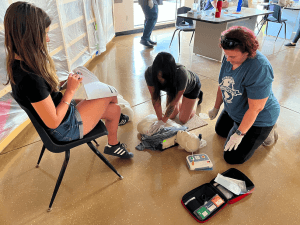

The best thing you can do, if you have any medical knowledge in a mass casualty situation, is to teach others what to do.

You don’t need to be a doctor to learn how to apply direct pressure, or even to pack a wound. People want to help. Most just don’t know what to do. And for some reason, they need the permission of someone who appears to be in charge, or at least who knows what they are doing.

You will be teaching while you are delegating, so be explicit. NOT “Somebody help this person,” but more like:

“YOU! Yes, YOU. Can you help this lady? I need you to press down really hard on her hip here, where it’s bleeding. No gloves? Here–stick your hand in this grocery bag. . . You here, yes YOU. I need your shirt right now. Can we have it please? Thanks! Here, use this. Cram it in that hole, and when you can’t cram any more in there, press down as hard as you can on top. She needs your help! You can save her life doing this. I have to check on the others. Have you got this? Thanks!“

If the patient in the grey shirt is a friend or relative of the lady in the red shirt, asking Red Shirt to help apply direct pressure or hold C-spine stabilization or whatever frees up this blue-shirted medic’s hands to take vitals, do blood sweeps, or look for other patients to help. Or she could find more bystanders and ask them to assist Red Shirt as necessary. Plus, even if Grey Shirt dies, Red Shirt will be able to look at herself in the bathroom mirror every morning for the rest of her life, and know she did what she could do. The rest of it was up to a Higher Power.

Staying on your feet, flitting from patient to patient and bystander to bystander should help you to stay global.

–George H, TECC / TCCC instructor

All injuries pictured in this article were simulated.