Heckler & Koch P9S DA to SA

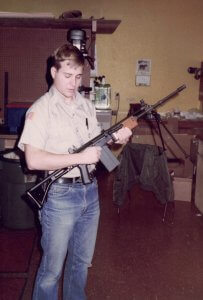

I worked at a civilian firing range from 1984 to ’86. We were armed in the course of our duties. The first year I carried a Smith & Wesson Model 586 (see The Smiths for related info). After that, I carried a GI .45.

Sometimes, when that M1911A1 was visiting the gunsmith or otherwise unavailable, I carried a friend’s H&K P9S in .45 ACP.

The P9S was a double / single; the trigger could both cock and fire the pistol. After the first shot, it cocked itself. It had a side-mounted decocking lever, similar to the SIG P series, except that the lever could also cock the P9S. If memory serves, I carried it the traditional way, with the trigger forward so that the first shot would be double action. I know (because I wrote it down) that I practiced presentations with multiple shots, starting double action. Even then I was a huge believer that:

As ye train, yeah verily, even thus shall ye fight.

The P9S had a slide mounted safety I carried in the “fire” position. Since the first pull was double action, a manual safety would be redundant. After all, the Smith & Wesson revolvers I’d carried for the Air Force, and the Smiths I carried on duty after that (with rounds in all 6 chambers) started with the hammer down; they didn’t have any sort of manual safety whatsoever. Even the AF let me carry them that way–’cause that’s how they were designed to be carried.

Besides, slide mounted safeties are hard to reach with the gun hand (they also tend to get wiped on or off at inopportune times while manipulating the slide).

The Double to Single Auto Pistol Concept

For those of you who don’t know,

the main purpose of double to single trigger action is to make training less important; in actual practice, Double to Singles actually require MORE practice to master.

It can be done, but you have to work on it.

The idea is, the first trigger pull is long and heavy. Not only does this allow you to keep the hammer (or striker) in the “safer” forward position, with the mainspring (or striker spring) at rest; it also means you REALLY have to want the gun to go off to pull the trigger all that far through all that resistance. Since the hammer / striker is already in the forward position, with little or no stored energy from the compressed hammer / striker spring, we can leave a DA–>SA pistol with the safety OFF. That means one less thing to forget (assuming any existing manual safeties haven’t been wiped on by accident, or left on by ill-advised policy). In a moment of intensified stress; you can just point, pull, and pray.

If you just shot your friend by accident, the manufacturers of Double to Singles assume you will take your finger off the trigger, the very best way to get ANY firearm to make fewer loud noises.

If you don’t stop firing, the manufacturer assumes you wanted to, so they use the recoil energy to make it easier for you to hit after that.

Each time the slide of a DA–>SA auto pistol reciprocates, it cocks the hammer for you. It stays cocked, till you decock it (with a decking device, or manually pulling the trigger while controlling the hammer with a thumb or between the thumb and forefinger, as one must with, say, the Makarov).

Downsides of DA–>SA

The reason a DA to SA requires more training is because you have to know and expect two different trigger pulls. Most novices go to the range, chamber a round (cocking the hammer), fire off a box of ammo that way, and leave, thinking they have “trained.” Because they are not accustomed to the heavy DA trigger pull, when they do need the gun to save their lives, the first round goes into the dirt, because they end up cranking on their trigger finger (and by association, their whole hand, including the other fingers) much harder than they expected.

Then, feeling (quickly and subconsciously) that they must mash the trigger hard again, they crank off their second shot (the first lighter SA pull) into the air while the gun is still in recoil from the first shot. People who don’t have the forethought to practice the DA to SA transition by decocking between controlled pairs in practice also tend to practice poor recoil control.

This can be fixed with sufficient training.

For dry practice, remove the ammo from mag well AND the chamber. Point your DA–>SA at something that will actually absorb and stop a bullet, like a planter full of soil. You can do a lot of DA-only to build up strength in your trigger finger (if you’re not used to DA). Later, have a friend cycle the slide for you while you hold the trigger to the rear after the first (DA) pull. Relax your finger till you feel the first click, and practice a relatively gentle SA pull. After scanning your environment (move your head, not just your eyes), decock and repeat.

Karl Walther adopted the DA–>SA for his P38, a standard German sidearm of WWII. I understand that John Moses Browning considered DA–>SA for his GP35 High Power, but then rejected the idea, choosing instead an SA-only with a frame mounted, manual thumb safety.

Function Testing the P9 Series . . . and just about everything else

The P9S was very reliable, but it would be a stretch to even call it a passing fancy; it was just something I borrowed when I couldn’t use my M1911A1.

That job at the pistol range paid minimum wage, but one of the perks was being able to fire a huge variety of other people’s guns that I could not, at the time, afford to buy. I got reloads at wholesale price (and on credit; one time I had to write off my entire paycheck, primarily on what I owed for ammo).

That job at the pistol range paid minimum wage, but one of the perks was being able to fire a huge variety of other people’s guns that I could not, at the time, afford to buy. I got reloads at wholesale price (and on credit; one time I had to write off my entire paycheck, primarily on what I owed for ammo).

An eclectic crowd came into that shooting range. Some (not as many as you might expect) were off-duty cops. Some LE agencies actually had a contract with our range to run their quals there.

One of our regular customers had been a WWII OSS operative. He used to walk in once a week with a bowling ball bag full of different handguns; even such esoteric offerings as a Sauer 38H, which had been issued to Luftwaffe pilots in WWII. I wondered how he got it.

One red bearded customer, I figured out, had been a mercenary; he never identified his vocation but said he used to travel a lot. He shot a Browning Hi-power and wore a faded cammo bush hat.

I got to see different shooting styles.

I learned that some of the pistols touted as awesome in gun periodicals were really only mediocre. I also got to see which ones, like the H&Ks, were truly reliable.

I got to take the Beginning and Intermediate Defensive Pistolcraft courses we offered, taught by a Gunsite grad, for free. In all, I was blessed that my girlfriend had been perusing the want adds and found that job for me. It set me up on the path I followed for the rest of my life. Almost like the Universe has some grand plan tailored specifically for each and every one of us . . .

P9 Variants

The P9 (without the S) was a single action only version of the same pistol.

Th P9 series could also be chambered in 9x19mm, as well as .45 ACP (11.43x23mm).

H&K Innovations Showcased in the P9 Series

Polymer Pioneer

The H&K P9 series, along with their VP70, were among the first polymer framed pistols. Polymer is lighter and does not rust. European plastics were still somewhat fragile; the front of the trigger guard on that P9S was cracked (as were the dash boards on many European sports cars after a few years in the Southwestern heat). Gaston Glock improved on that idea, developing stronger, longer lasting polymers and better ways to embed structural supports within a plastic frame.

Polygonal Rifling

The Heckler & Koch P9 & P9S were some of the first widely produced modern pistols using polygonal rifling, which is to say there are flats, instead of lands & grooves, inside the barrel that impart the stabilizing twist. Polygonal rifling results in a more air-tight bullet to barrel fit. With traditional land and groove rifling, the grooves have to be wider than the bullet diameter. The lands have to be narrower than the bullet so they can bite into the projectile and twist it somewhat violently. Polygonal barrels also rapidly impart a stabilizing rotation to the bullet, but they do so by squeezing it on several sides, rather than biting into it. This may or may not result in less bullet deformation, but it does mean that, with polygonal rifling, less of the propellant gasses will blow past the sides of the projectile. This results in higher velocities for any given load, compared with the same load in a conventionally rifled barrel of the same length. Polygonal rifling also does not wear out as rapidly as conventional land and groove rifling.

Polygonal rifling is also easier to clean, as less of the bullet is shorn off and left in the barrel.

Gaston Glock used polygonal rifling on his 17th design, the Glock 17, which was far more successful than the H&K P9, P9S, or PSP / P7.

There are drawbacks to polygonal rifling. Polygonal barrels, while easier to clean, are not maintenance free, they still must be cleaned out. Because there is a more hermetic bullet to barrel fit, cartridges with a steep pressure curve (like .40 S&W) will spike to even higher pressures in a polygonal barrel. When boring out 9mm barrels to accommodate 10mm (.40 S&W) bullets became the rage, some IPSC competitors who shot thousands of lead rounds through .40 Glock barrels (higher pressure cartridge, less metal around it) blew up some Glocks by not cleaning them regularly enough.

Another drawback of polygonal rifling is that it may not stabilize the bullet enough, particularly some lead 9mm loads. I never had that problem shooting .45s through that P9S, but the 2nd Generation Glock 19 I used when I went to the Wyoming Law Enforcement Academy did not work well with my agency’s issued lead practice reloads. I frequently got keyholes as close as 7 yards. This would have freaked me out if I had not witnessed the same phenomenon with certain lead bullet / barrel combinations when I worked at that pistol range a decade before.

Perhaps ironically, the latest generation of Glocks have eschewed the polygonal rifling which was originally touted as one of their advantages, in favor of increased accuracy from traditionally rifled, slightly tighter chambered barrel. Whether the “marksman” barrels are more accurate enough to make up for the potential loss of reliability in the field remains to be seen.

Cocked Hammer Indicator

The P9 and P9S had a hammer, but it was entirely encased in the back of the slide (when forward) and the back of the frame (when cocked). A pin protruded from the back of the P9 / P9S showing you when the hammer was cocked.

I’m guessing the internal hammer was meant to keep the mechanism from collecting dirt, dust, and lint. A little pin was not necessary to see if the hammer was cocked on my M1911A1–because you could see it.

Loaded Chamber Indicator (LCI)

The P9 / P9S a loaded chamber indicator above and to the rear of the chamber, about where the extractor of a Luger is.

LCIs are quite common on modern pistols. For first time buyers who don’t know much about guns, they seem like an important feature. For those who check their chamber before they strap on a pistol, and don’t treat an “unloaded” gun much differently than they would a loaded one, LCIs are a nice to have, not a need to have. To me, most LCIs (except those which are really extractors that stick out a bit more when there is a round in the chamber) are just one excess moving part that can break.

Still, the H&K P9 series had an LCI when most pistols did not.

Roller-Delayed Blowback

Quite unusually for a pistol, the P9 series used the same stamped construction methods and roller delayed blowback type locking system as the H&K MP5 SMG and the CETME / G3 series rifles. As with the Walther PP series, the Makarov, the H&K VP-70, and the H&K P7 / PSP, the recoil spring of the P9 series wrapped around the barrel.