What you don’t know about Domestic Violence

In the bad olde days, people sometimes hit each other. Even friends and lovers would. The occasional slap or even bar-room brawl was considered unfortunate at worst, and at best, inevitable “boys will be boys” behavior.

I’m not defending that. Just stating historical fact.

Also in the bad olde days, women and children were essentially chattel.

Property.

If a man wanted to smack his wife, or girlfriend, or even the kids around, the powers that be took only passing interest.

Our society has evolved for the better in many ways. As time has progressed, we have become more acutely aware of the long-term effects of Domestic Violence, or DV. But many people who are not in law enforcement still don’t understand the underlying processes of DV.

On the one hand, DV is not rocket science. An angry drunk gets off on hurting those closest to him. He uses violence, or the threat of violence, to intimidate them. He intimidates them to keep them under his control.

But our lack of understanding of the patterns and nuances of violence, particularly domestic violence, doesn’t make it go away. Our ignorance serves neither women nor children nor men.

The Cycle of DV

When most people think of the “cycle of violence,” we are thinking in terms of the cycle of life. A husband beats his wife in front of the children (or beats the children themselves). Those kids grow up normalizing interpersonal violence between relatives and loved ones. They become wife beaters, abused spouses, and / or child abusers themselves, and then exhibit those behaviors in front of their own children. And that chain of events continues unbroken.

But Domestic Violence itself also follows predictable patterns. Our understanding of those patterns is critical to our combatting DV, and to our understanding of how and why historical approaches to DV have been ineffective.

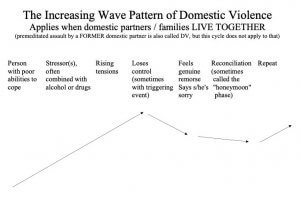

For the purposes of brevity I will sometimes refer to the abuser as a “he,” and the victim of DV as a “she” or a child, as that is most common, while recognizing that DV occurs in same sex relationships as well as heterosexual ones. More and more women are beginning to break the glass ceiling of beating men. But for ease of understanding, as well as in keeping with most historical statistics, the abuser will sometimes be referenced as “he” in this narrative. DV victims will sometimes, again for clarity and simplicity, be referred to as “she.” Fig. 1. This diagram illustrates the archetypical DV pattern.

Fig. 1. This diagram illustrates the archetypical DV pattern.

- A person (almost invariably a male) has anger management issues and / or lack of self control. Alcohol, a disinhibitive (something that allows a person to remove inhibitions on, or self control over, their behavior), may be involved. Crack cocaine, methamphetamines, and certain other “uppers” are know to increase agitation, paranoia, and the propensity for violence. Chemicals are not always involved in DV, but they frequently are.

- Stressors occur. This could be an overbearing boss, not having a boss from not having a job and therefore little income, high bills, a baby that won’t stop crying, or whatever. There is not always a “triggering” event. Sometimes, it’s just been too long since the abuser beat someone.

- The anger reaches a flashpoint, and the person who lacks self control lashes out at the most convenient target: usually a spouse, girlfriend, or child. Again, we like to be egalitarian and say it could be a woman beating a man, or a man beating a boyfriend / woman beating a girlfriend. Things like that do happen. But the vast majority of the time it is a male beating a female or a minor. This is sometimes called the “acute” phase. While the beating and screaming is going on, a neighbor or frightened child calls the cops.

- After the beating, the abuser’s anger is spent. He looks upon the victim with genuine remorse, or at least pity. He may apologize, or even hold the victim gently. This is the only time in the entire relationship when the abuser treats the DV victim as the victim believes they should. This is sometimes called the “honeymoon” phase.

The conciliatory honeymoon phase is, almost invariably, when the cops get there.

Former Responses to DV

Historically, when the police arrived during the honeymoon phase, they spoke with the family. Everybody seemed to be getting along fine. It was considered a private matter that they should work out between themselves. The cops might suggest that she stay with her sister or her mom for a few days. The couple was encouraged to cool off, and then work things out between themselves.

Unless they caught him in the act, or the abuser got stupid with the cops, he usually was not arrested, especially in rural areas (see below). He didn’t even have to leave his house. The only thing he might regret would be not getting hot meals for a day or two.

But the abuser knew she would be back.

Cops who had been to the same residence several times for DV might actually feel she almost deserved it for not learning her lesson the first five times, and leaving him. They ignored raw economic realities when most women did not work and the abuser was also the sole bread winner with some custodial rights regarding the children. Abusers typically kept thier wives from getting driver’s licenses, which would mean freedom of navigation (and to leave).

Police, like anybody else, are and have always been human beings. There are as many different mindsets are there are cops. At the risk of stereotyping police, though, its instructive to see the world through their eyes.

Police stand up to bullies–often much larger and stronger bullies who may be on PCP–every single day. Sometimes, especially in big cities, several times a day. Accordingly, the law enforcement career field is one in which “Type A personalities” can be useful, for dealing with crooks who are, by definition, Alpha wolves. Not every cop is a Type A–I certainly never have been–but being a Type A is certainly a bonus in a line of work in which there is no nice clean neat harmless politically correct way to put handcuffs on somebody who violently resists being handcuffed.

But there is a duality to the “sheepdogs” which does not exist in the wolves. Wolves prey upon the helpless. Sheepdogs protect the helpless and the innocent. People who get into law enforcement often have a bit of a Galahad complex; they want to be the knight in shining armor who saves the maiden from the dragon–especially when they are rookies who are “still pooping their Academy food.” Several years into their careers, it becomes painfully apparent to them that they may or may not get the dragon, but it’s almost always too late for the maiden.

They race around from call to call to call with their hair on fire, but despite their best efforts, they cannot be everywhere at once (nor, in a democratic society, would we want them always looking over our shoulders). As far back as the 1970s, USMC Lt Col “Jeff” Cooper wrote:

“Our police do what they can, but they can’t protect us everywhere and all the time. All too often they cannot even protect themselves. Your physical safety is up to you, as it really always has been.”

—Principles of Personal Defense, pp. 77 – 78

Knowing this in the certainty of their experience, police have little patience for those who will not take measures, even simple measures like locking the door, to protect themselves. They would not live with someone who beat them, and while they had some vague notion that it wasn’t easy for a woman to leave the father of her children, especially for those without a strong support network, they could not understand why a woman would ever stay with a wife beater.

Police would gleefully “tune up” a wife beater caught in flagrante delicto. But the seventh time they returned to the same apartment on a domestic disturbance call, they began to lose patience with the victim as well as the perpetrator. It was NOT the victims fault, but, they felt, the victim kept putting herself in a bad position by taking the abuser back.

Police on larger metropolitan departments were rated by how many statistics they generated (that started to change in the ’90s and early 2Ks, when many departments went to a model of “Why are there so many burglaries in your patrol area?” and high stats became discouraged). Consequently, metro departments were, historically, more likely to effect an arrest for DV.

Rural and small town police officers, who had large areas to patrol with relatively few officers, were more likely to seek non-judicial solutions, as any arrest took a significant percentage of their officers off the road for an inordinate amount of time.

I witnessed this myself, as a ranger patrolling a large state park in Wyoming. Most of our problems happened at a place called Sandy Beach. On weekends, Sandy was essentially a 2-mile, open-air singles bar. It was many miles around the far side of a lake from from the main road to Wheatland, the county seat. It took about 20 minutes on windy, narrow, shoulder-less roads to get from Sandy to the main highway, and 40 minutes from there to the Platte County jail.

Once, when we had several witnesses–and bruising–indicating that a man had beaten his wife, my boss elected to diffuse the situation by helping the couple to relocate their camp away from the other campers, who had threatened their own extrajudicial responses to the wife beater. This had the unintended result of making her more isolated from help and potentially in greater danger. The boss decided that would be less risky for the entire populace than taking half the force off the job for 2 – 3 hours to transport and book a suspect on a very busy holiday weekend.

It wasn’t my call, but in hindsight I wish I had insisted on a jail time for the offender. I was pretty low on the totem pole at the time, but I might have been able to persuade the jefe. We had no further trouble from their campsite that weekend–we monitored it as closely as time and crowds allowed–but the abuser deserved some jail time.

Even in the bad olde days, when an abuser was caught in the act or had severely beaten someone or if it was aggravated assault (say, with a hammer, tire iron, or some other weapon), the cops would put usually the “habeas grabbus” on the abuser. The blue knights who had, in their minds, just rescued the maiden from the dragon were often confused and annoyed–sometimes injured or killed–when the DV victim then came to the abuser’s aid (see Bizarre Coping Mechanisms below).

Why That Paradigm Wasn’t Working

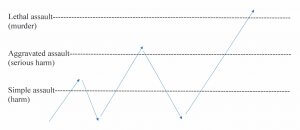

The problem is, for people with a propensity toward violence, the release of striking someone is like a drug. It satisfies a craving, for a time. Fig.2: As with a drug, abusers build up their tolerance. It takes more and more violence to satisfy their violent urges. What starts out as punching her in the stomach becomes kicking her in the face, beating her with a golf club, or drowning her in the toilet.

As with a drug, abusers build up their tolerance. It takes more and more violence to satisfy their violent urges. What starts out as punching her in the stomach becomes kicking her in the face, beating her with a golf club, or drowning her in the toilet.

The abuser might recognize that their urges are wrong and inwardly battle against their desire to punch a domestic partner. The problem is, the longer they resist, the greater their level of anger when they lose that battle. The pot is boiling hotter by the time the dam bursts, so their rage is more explosive, resulting in greater injury to the victim(s).

The longer the abused victim waits to leave the relationship altogether, the greater their peril. When left unchecked, DV almost always becomes fatal.

Bizarre Coping Mechanisms of DV Victims

Humans are the ultimate survivor species.

Survivors of DV typically cope with it in two ways that might not seem to make much sense to people who have never been beaten by a family member:

- Picking a fight, and

- Siding with the abuser.

Picking a Fight

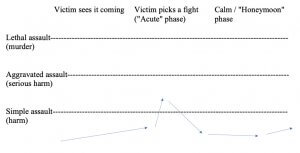

Those who have been living under the yoke of Domestic Violence for long enough will recognize the signs that another beat-down is coming. Realizing, perhaps subconsciously, that the longer they put it off, the worse the beating will be, they create their own precipitating event to get it over before their domestic partner has gotten too worked up. They pick a fight over something trivial. They literally goad the abuser into beating them. Fig. 3:

Our instructors told us about this coping mechanism when I went through the police academy in 1995. It explained something I had witnessed with my own eyes a few years before.

When I went through Med Tech school for the Air Force, one of the “pipeline” (straight out of basic training) students was a young airman I’ll call “Sarah.” Sarah was married. Sarah would come into class late sometimes, with a black eye and a puffy face.

The cadre spoke with her. They had mandatory reporting requirements, and were dealing with it through official channels.

Later, I heard a rumor that some of the pipeliners in our class had been smoking marijuana. Nobody in the civilian world seems to care about that these days, but back then, among military personnel, it was a big deal. As the old man (I was 30), I was the designated class leader. I, too, had mandatory reporting requirements. Before reporting it to our leadership, I had to know what to report. I went to various students to ask if they knew anything about it.

Sarah was living with her husband in separate quarters, but she was hanging out with two of the other airmen in the barracks when I questioned them. Sarah became irate and abusive. I was an NCO doing what NCOs are supposed to do, but she railed at me. She got right up in my grill and screamed–I could feel her breath on my face. She actually dared me to hit her.

Seriously? Hit her?!?

Yup.

Why she thought I would strike a subordinate–especially a woman (call me a chauvinist pig if you want)–while conducting an inquiry as to who may or may not have done what, when, I did not know. It wasn’t till I was in Peace Officer Basic three years later that I began to understand why Sarah was literally trying to goad me into violence. That was how she dealt with any form of confrontation. Get the fight started, so we can get it over with before it turns really bad.

Of course, some people are just psycho. But Sarah wasn’t crazy in class. She seemed like a normal person to me during our day to day interactions.

Unholy Alliances

Another DV coping mechanism that is perhaps easier to understand is siding with the abuser.

Throughout the last half of the 20th Century, and well into the 21st, British prime ministers came and went, but Queen Elizabeth was always there. Similarly, police come and go, but the abuser is a constant in the DV victim’s life.

Even if the cops are taking the abuser away to cool off in the drunk tank at jail, the DV victim knows he’ll be out before they can finish the paperwork. This was true even before COVID and BLM. Now booking is literally a revolving door.

As mentioned above, police perform cuddleus interruptus when they barge in on the post-beating honeymoon phase. Pehaps they get into a fight with the then-conciliatory abuser. Even if they get there during the beating (which is rare), the victims know their tormentor will be back. The victim seeks to form an alliance by pointing out a common enemy: the police.

DV victims have been known to stab cops in the back with kitchen knives as they try to cart away the handcuffed abuser.

When I was a rookie cop, my FTOs (field training officers) told me to never put on my seatbelt till I was at least a hundred yards away from the scene of an arrest. “Breadwinner may lose his job when he doesn’t show up for work tomorrow,” they said. “As soon as she realizes the paycheck is going away, she may come out with a shotgun. You don’t want to be stuck in this car if that happens”

As with criminals who smuggle people, abusers often intimidate their victims into not testifying against them. It’s frustrating for police and detectives to take the time and effort to conduct an arrest, book the suspect, build up a case, gather evidence, maintain the chain of custody, conduct interviews, get affidavits and warrants if necessary, and go through trial prep, only to find the abuser and the DV victim have just reconciled and are on vacation in Tahiti.

Police are only human. Sometimes, frustrated cops give up, at least with certain types of cases. They want to make sure that their efforts will bear fruit, so they ask the DV victim if they will be there all the way through the process or if they are going to change their story. They put DV victims in a very uncomfortable position when they ask, sometimes even in front of the abuser, “Are you willing to press charges?”

Like many (perhaps most) aspects of law enforcement, the misused term “pressing charges” is misunderstood. Frustrated, overworked (or sometimes, lazy) cops who’ve been to the same apartment for DV several times occasionally capitalize on the public’s ignorance or the law and police procedure by using the phrase “are you willing to press charges?” to get out of making an arrest.

The phrase is practically meaningless, in legal terms.

Criminal charges can be filed (or not) irrespective of the desires of any victims. Criminal charges are not and have never been dependent upon the desires of the victimized. Criminal charges are between the state and the accused alone. But sometimes investigators use the phrase (“Now, the store owner says he’s not planning to press charges as long as you agree to pay for the damage”) to elicit a confession, or to seek a civil, as opposed to a criminal, resolution.

Or to get out of making a fruitless, time consuming DV arrest, when they know she’s just going to take the abuser back, often before the end of the day.

May versus Shall

While they may not have been aware of these patterns of violence and LE response to DV, many legislators could see that domestic violence is not going away, and may in fact be getting worse.

One effort some legislatures have made to combat domestic violence was by changing language in statutes regarding DV arrest from “may” to “shall.” Instead of an investigating officer deciding whether or not to make an arrest based upon the totality of circumstances they can see with their own eyes on the scene, the officer is now obligated by law to arrest someone, if there is any evidence that anybody had hit somebody else.

Which is OK with most people. But the devil is in the details.

As with most legislation, the switch from “may” to “shall” was well intended, but had some unintended consequences.

One was a chilling effect on women defending themselves from abusers.

Every culture throughout the world recognizes that human beings have the right to use force if necessary to defend themselves from serious assault. But when the switch was made from “may” to “shall,” we abrogated that right, for victims of domestic violence.

Abusers, like active killers, are for the most part cowards who only prey upon the weak. At the first sign of serious resistance, they often wilt, or choose a different victim.

This is not always the case; with some testosterone dripping neanderthals who “like it rough,” moderate resistance only encourages them. Only serious resistance (e.g., rolling pin to the head, shot with a firearm) will make those abusers stop abusing. But let’s consider a hypothetical from the first group mentioned (probably the majority of abusers):

Let’s say Abuser A beats Victim B until Victim B finally says “Enough is enough.” She socks him right in the nose. He gets the message and backs off. Her single, carefully placed use of force has ended the domestic violence incident, perhaps even caused A to reconsider his outlook on violence as a means of resolving domestic issues.

B didn’t start it. It’s not B’s fault. She’s covered with cuts and bruises in various stages of healing, and he only has a temporarily bloody nose.

But when the cops get there, thanks to that tiny little word “shall,” B gets arrested, and thrown into the same jail as A. Their kids go into the custody of CPS, perhaps even foster care, because she now has a record of violence. That she was modeling how to stand up to bullies is not relevant. ALL violence, even in self-defense, is now a mandatory arrest offense. B gets a permanent DV criminal record. That means, among other things, that she can never own a firearm (see Lautenberg, below), even after the divorce when he begins stalking her and leaving death threats on her answering machine.

DV Criminal Damage

If your 40 year old cassette player just ate your favorite Allman Brothers tape, and you want to take it into the garage and beat it apart with a lead pipe so it will never massacre another defenseless work of art again, you have that right. It may be ecologically unsound, and you may regret it afterward. It’s probably smarter just to clean the heads. But it’s your boom box, and your business.

Just don’t do it in front of anyone you live with, or where they can hear you. At least not in Arizona.

Arizona has a “DV Criminal Damage” statute. Actually, if you commit any of a series of crimes, including criminal damage, in front of your family or paramour, you can be charged with Domestic Violence.

Lemmie ‘splain.

Criminal Damage includes a wide range of vandalistic activities, including “tagging.”

Crimes are either misdemeanors or felonies. Misdemeanors are minor offenses. Serious misdemeanors are punishable by up to 364 days in jail. Felonies are serious crimes. The most minor felony is punishable by over a year in jail.

DV can be a misdemeanor or a felony. Slapping a husband who stumbles in drunk with somebody else’s lipstick on his neck is a misdemeanor. Setting the same philandering husband’s bed on fire as he sleeps off his bender (it’s been done) is a felony.

A person who has so many anger management issues that they punch holes in walls, it’s a safe bet that eventually they will punch somebody. Picture an angry man intimidating his spouse by smashing a watermelon, and saying “This is gonna be your head!”

Attempting to prevent DV before it happens, the Arizona state legislature opted to include criminal damage in the list of crimes which, if committed in front of a domestic partner, roommate, former lover, or relative, is a crime of Domestic Violence.

So neighbors hear people arguing and hear bottles breaking against the wall. They call the cops, who get there as the potential abuser is punching holes in the wall. They arrest him for DV criminal damage, possibly averting injury to the spouse. Chalk one up for the good guys and gals.

But picture this. You and your boyfriend are having an argument. He locks you out of the house. YOUR house. You’re going to be late for work, so you knock a window pane out of the door (YOUR door). He doesn’t even live there (although, since you previously invited him to spend the night, he wasn’t legally trespassing). He has his own place, and you’re not married (AZ is a community property state). You grab the keys, don’t say a word to him, and head to your car to go to work–only to find it blocked in the driveway by police cruisers, because the neighbors heard the argument and thought cops should get there before things got out of hand.

They separate you and interview you both. Nobody hit anybody. Who broke the window? they ask. You did, you admit, explaining how he was being an ass; he would not let you in or even throw the keys out to you, it’s not even his house, and you need to go to work. OK, they say. Turn around please. They cuff you and cart you off to jail for DV Criminal Damage.

No, I’m not making this story up.

DM Criminal Damage is the most minor of minor DV offenses. People who have more time than money are likely to plead nolo contendre (no contest) to such minor charges. That means they’re not going to fight it. Nolo contendre is not admitting guilt, but they still get convicted. They get a fine, perhaps some court mandated Anger Management counseling. Unless they need a security clearance for their job, many people never fight misdemeanor DV charges after getting into a spat with their spouse. It’s not worth the time and treasure to them.

The Lautenberg Amendment

Technically, it’s a misnomer to call it THE Lautenberg Amendment, although most people (including I) do. It’s like saying “THE science,” as if scientific research is some monolithic thing that is already set in stone, we already know everything, and there won’t be any new discoveries to challenge to our current theories tomorrow.

Frank Lautenberg amended several federal laws during his time as a US Senator.

One of them amended Title 18 of the United States Code, specifically, 18 USC 922(g), which is a list of persons prohibited to possess firearms. Lautenberg’s amendment added anyone who had ever been convicted of misdemeanor DV to the list.

On the face of it, the Lautenberg amendment to the Gun Control Act of 1968 makes a great deal of sense. People who can’t control their anger and assault their sig-Os really shouldn’t have a gun. I couldn’t agree more.

Lautenberg has withstood some challenges in lower courts, including at least two on the basis of it being ex post facto. That’s when somebody does something that’s not against the law, and then somebody changes the law to make it illegal, and then convicts the person who did something that was legal when the accused did it. In the case of Lautenberg, a person who had a misdemeanor DV conviction was allowed to own a gun and ammunition. Then Lautenberg became law in 1996; that same person became a federal felon with the stroke of President William Clinton’s pen. Perhaps they would have mounted a more serious defense, or paid for an attorney, if they knew a misdemeanor conviction would eventually make them a felon and deprive them of civil liberties.

Technically, after Lautenberg took effect, they were not even allowed to transfer the gun to somebody else, forcing them to remain a felon. I suppose they could charter a fishing boat and throw the gun in the ocean miles from shore. But if they once opened a box of .22 ammo upside down, and one of the cartridges wound up lost under a couch cushion, they’re still a felon, as 18 USC 922(g) prohibits the possession of a firearm OR ammunition.

Article 1, Section 9, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution states:

No Bill of Attainder or ex post facto Law shall be passed.

At least one of those Lautenberg cases, US v. Brady, was denied certiorari by the higher court. That means they chose not to review it. Probably they refused to grant certiorari because, quite frankly, Lautenberg is blatantly ex post facto, and they would have had to find it so, if they chose to review the case. Like those judges and the rest of the voting public, I certainly don’t want wife beaters to have guns.

Thus far at least, Lautenberg has withstood lower court challenges. I believe Lautenberg will continue to be upheld, or little challenged. Not many people are willing to go to bat for wife beaters (or even perceived wife beaters) in the name of civil rights. Accusations of DV, like child molestation, never play well to a jury.

Speaking of, one technicality of Lautenberg is that the misdemeanor DV conviction must have been triable by a jury, even if the case never went to court. In many municipal courts, minor misdemeanor offenses are not considered worth the time and effort of jury selection.

Many in the military and law enforcement lost their jobs after Lautenberg passed, because they could not possess a gun–not even a gun that lawfully belongs to Uncle Sam, who only loaned it to them while they were on duty (most members of the military only handle firearms once a year during annual qualifications). Some of those people were wife beaters who really shouldn’t be allowed to serve. Others, though, had gotten into a lover’s spat, got arrested on a misdemeanor DV charge, and didn’t have the time, money, or inclination to fight the charges for such a petty crime. A misdemeanor conviction was no big deal.

Then–wham!–in 1996, they became unemployable.

Again, I am totally behind the spirit of Lautenberg. But as with almost all federal (and most state) legislation, Lautenberg “measures with a micrometer but cuts with a chainsaw.”

Think back to the lady who broke her own window to get into her own house that she’d been locked out of by an asinine boyfriend. The same way you might bust your own window, if you’d locked your keys in the house and had to get to work or couldn’t wait to feed the dog or whatever.

Now let’s say that decades later, that same person with a misdemeanor conviction for DV criminal damage is working as a caregiver for an elderly veteran who owns a gun or guns. His noggin is still sharp as a tack, but he has a caregiver to help him with chores around the house, as physically, his body parts are getting past their expiration date. And no, I’m not making this part of the story up, either.

There is a legal term called constructive possession. I once put a prohibited possessor, a very bad man, in jail with constructive possession. The 9mm was under his car seat, but he was wearing a holster that fit it. We were able to establish beyond a reasonable doubt that he was in constructive possession of the firearm, even though it was not on his person at the time of the arrest. He’d been tried unsuccessfully twice before, for murder and kidnapping, but the witnesses kept disappearing. We were able to put him in jail as a prohibited possessor, using constructive possession.

Is our caregiver with the misdemeanor DV conviction in constructive possession of her patient’s firearms while she cleans his house?

If I go over to that house to train him, I can help him dry practice, but I’m skirting the edges of Lautenberg if I put one of those guns in her hands, even temporarily and under supervision, to show her how to safely unload it and lock it away it if he becomes incapacitated and must go to the hospital (which happens to the elderly from time to time). If she knows the combo to his safe, so she can put it away after he’s been handling it, she’s a prohibited possessor in possession of a firearm–a federal felony.

Is any valid civil purpose served by her ignorance, her lack of hands-on safety training with a dangerous instrument that is in her workplace, just because she broke her own window decades ago? Does she need to lose her job because he owns a gun?

It is possible to get old convictions for minor offenses expunged or set aside, if one has been behaving since then, as she apparently has. That takes time and money.

Lots of money.

Indeed, most of the so-called “common sense” legislation that has been experimented with for decades in high-crime states like California, and has failed to control or even limit violent crime, but is still being proposed nation-wide, is really just expensive red tape designed to discourage firearms ownership by making it too much of a hassle to jump through all the requisite hoops. The wealthy can afford attorneys to jump through those hoops for them. The poor (who are disproportionately minorities)–well, they’re just outta luck. And the poor are more likely to live in areas with high rates of violent crime.

I’m guessing that lady who helps the old man can’t afford a high-priced lawyer on a caregiver’s salary.

Again, I’m not anti-Lautenberg. I don’t want wife beaters to have guns. But we need to recognize that all legislation, however well intended, has unintended consequences.

Something must be done to curb this world-wide sickness of people wanting to hurt and maim and kill one another. We can start by understanding violence and learning its root causes. But more and more, people who really need to learn how to defend themselves against violence, with their bare hands if necessary (school teachers, for example), don’t even want to talk about it. They just want politicians to pass legislation restricting the tools murderers use.

We need to control killers, and their actions. Attempts to control the tools used by murderers–if that’s even possible–only force killers to obtain their tools illegally, or at best to choose different tools.

I’ve been on the receiving end of gunfire, but the closest anybody ever came to killing me when I was a street cop was with a Bic lighter, in a studio apartment full of natural gas.

In 2022, I visited Waukesha, WI, where a nut job had driven through a Christmas parade at 40 mph the year before, intentionally striking over 60 people, killing victims aged 8 to 81. He had been let out of jail a few days before, after hitting his ex-girlfriend with the same car. He had previously been released on a signature bond (i.e., no bond) for a domestic violence incident several months before that–and then failed to appear in court. Yes, you can still bond out of jail in this country, even when charged with failure to appear after bonding out before. It happens all the time. God bless America.

Our current approaches only encourage more violent crime.

We must focus our efforts on people’s behavior, rather than their tools. We should probably repeal parts of HIPAA that keeps critical mental health information out of NICS (the National “Instant” Criminal background check System for lawful firearms purchases). We must once again put violent criminals in jail and keep them there. That includes armed drug dealers who plea their possession with intent to distribute down to mere possession.

And we must be willing to discuss violence, even with people who feel differently about the solutions than we do.

–George H, lead instructor, Heloderm LLC

About our cover model

No animals were harmed during the making of this film. The lady with the black eye at the top of this article actually bashed her face on the pavement in Paris, France while she was trying out her recently rebuilt knee.

Sadly, Alexa Bartell, the young lady in the bottom photo, was in fact killed by a large rock intentionally thrown through her windshield on a freeway near Denver, CO, in what appears to have been a rock hurling spree. See “20-year-old fatally struck by large rock while driving, 1 of 5 similar incidents,” by Peter Charalambous.

I created those diagrams (figures 1, 2, and 3) for our Ladies’ Personal Protection and Violence Avoidance and Survival classes.