USAF Revolver Holsters & Ammo Pouches

Clamshell holsters

Sources I’ve read say the Elite Guard at Strategic Air Command (SAC) headquarters, Offutt AFB Nebraska, were the first in the USAF to order the Smith & Wesson Model 15s. Before long, Model 15 Smiths were issued Air Force-wide for APs (renamed SPs, Security Police, in about 1966), missile combat crews, and aircrews.

According to this display at the Strategic Air Command & Space Museum, the SAC HQ Elite Guard at Offutt AFB in Nebraska carried their staghorn handled Smith K-frames in patent leather clamshell crossdraw holsters. As far as I can tell, that’s a real K-frame Smith in the holster. Many if not most museum displays I’ve seen use replica firearms for security and legal / logistical purposes.

This would have been considered a “high ride,” referring to the altitude of the holster in relation to the belt (see below).

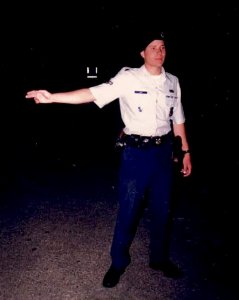

I wore a similar dark blue web belt with a chrome plated buckle bearing the enamel shield of SAC when I worked the Entry Control Points at FE Warren AFB, but since we were not as “ee-light,” our shirts were standard AF light blue shade 1550. We also used strong side Jordan holsters (see below).

When I worked at the gates, I called the Smith Model 15 I was issued “Lieutenant Gorman.” Like the hapless L-T from the movie Aliens, I anticipated that my .38 would be used with good intentions but would probably be somewhat ineffective.

Swivel holster and Bill Jordan holsters

In Southeast Asia, USAF issued a low ride holster, designated the GUU-1/P. It hung from wire hooks that ran though the brass eyelet holes in standard web belts. Because it hung so low, and because Air Force types rode to combat in a cockpit or a jeep rather than LPCs (leather personnel carriers, i.e., boots), the holster had a pivot so it could sit next to you on the seat.

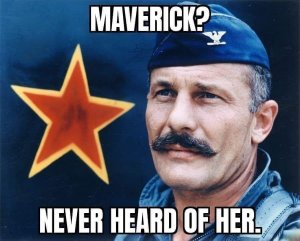

In this famous photo, Robin Olds spray paints a red star on the air intake splitter of his F-4, after downing a MiG-21 on 04 May 1967. Col Olds’ revolver was almost certainly a Smith Model 15. The handgun had to hang low so the butt would be under the pouches on the pilot’s survival vest. The canvas web belt wrapped around the outside of the G-suit’s abdominal bladder. My father served under Robin Olds and Daniel “Chappie” James Jr in the 8th TFW “Wolf Pack.” Image from Lou Drendel’s …And Kill MiGs, p. 11, although it’s probably an official USAF photo and I’ve seen it lots of places.

The revolver was secured in the holster by a leather strap that wrapped behind the hammer, below the spur, and snapped to the side of the holster well below the grip. The Bill Jordan holster the Air Force issued me in 1986 still had that type of strap, albeit slightly shorter and easier to get to. I guess the idea was to make drawing the pistol a deliberate, two-step process (see below for my workaround). Many civilian police holsters had similar straps in the 1950s but by the 1980s, “level 1 retention” usually meant a thumb snap that could be deactivated by holding your thumb stiff and executing a chopping motion as you established a proper grip on the handgun while it was still in the holster.

My old friend Greg G, a former Marine who taught firearms for the USBP (and later, for Heloderm) was digging through one of those dusty cardboard “used holster” bargain boxes you can still sometimes find in mom ‘n’ pop gun stores, and bought me a matched set of ‘Nam era USAF .38 revolver holster and dump pouch. The back of the swivel holster reads:

HOLSTER ASSEMBLY

GUU-1/P

1095-819-8591

J. M. BUCHEIMER CO. 1968

F.09603-68-D-0232

U. S.

The GUU-1/P holster had a small notch in front, just below the rear sight, which I assume was meant to speed up the draw ever so slightly by enabling the user to clear the leather with the muzzle without raising the pistol quite so high.

Instead of a notch below the front sight, the “Bill Jordan” type holster the USAF issued me in 1986 had a leather extension that came up to protect the rear sight. The rear sight of the Model 15 Smith was adjustable for both windage and elevation and was probably the most fragile part of the handgun. I didn’t plan on dropping mine, and it only cleared leather when unloaded at the end of the shift for turn in, but during a shift, things tend to get banged around, even in the leather.

There’s an old saw about leaving three security police troops in a room with two bowling balls for an hour. When you come back, one of the bowling balls will be missing, the other will be broken. When you ask them about what happened, the first will say he or she has no idea; they didn’t see anything. The second will claim that they were asleep when it happened. The third will swear, “Man, this post has been like that for weeks”–even if they had relieved you on that same post 12 hours before, and there had been two bowling balls when you left.

So given a choice between a tab of leather to protect the sight (Jordan holster) or a notch in the leather to save me a centimeter or two of elbow motion (GUU-1/P), I guess I’d rather have the protective tab of the Jordan, even with its ridiculous trigger cut out (see below).

The photo above shows the large, silver swivel in the GUU-1/P on the left, where the body of the holster pivoted from the part that hangs from a belt by the wire hooks above it–both of which, along with the snap on the retention strap, are so shiny they seem out of place on a combat duty holster. The pivot on the opposite side, next to the user, is covered with leather, but the outside, which is mostly behind the butt of the handgun, is not. Don’t know if the inside is covered for comfort, or to keep it from rusting, or both.

These photos also show the relative “ride” of the ‘Nam-era (mid-1960s) USAF holster, which would have hung only a centimeter or two higher on a web belt, and the holster from the late cold war (mid 1980s). The newer (or less old) holster on the left would be considered a mid ride. The holster on the right, hanging down below the belt is a low ride, almost but not quite a “thigh” holster like Han Solo’s.

By that time, most civilian LE duty revolver holsters were “high ride,” with the cylinder at about belt level and the butt well above the duty belt. The Bianchi 5BHL I carried the Sarge in at the Marksman Pistol Institute (see The Smiths in Triggers I’ve Known) was a high ride.

The high ride helped with retention (I often would pin my elbow against it if folks got behind me in a crowd). Becasue the thumb could slide against the body without running into leather, high ride also enabled the user to get a complete grip on the handgun in the holster–which saves much time and readjustment after getting the gun out.

If one was wearing a ‘Nam era flak vest, though, even the low ride of the GUU-1/P might not be low enough. The “drop rig” extension pictured below helped get it out from under the flak vest, as well as giving one a low hanging, gunslinger look like Lorne Greene in Bonanza. I don’t know if the drop extension below is home-made or was issued.

We used to cut up spare web belts and hand-sew “Kovach clip” extensions for our duty web belts, for when we needed to take them off our hips and strap them around the outside of a flak vest.

The holster in the photo above, which clearly shows where it pivots (as well as the notch in front), is in a display at the National Museum of the Air Force at Wright Patterson AFB in Ohio. The uniform and other artifacts in that particular display were worn & carried by USAF Security Police Airman First Class (A1C) Ernie Childers, when he was a K-9 handler at Udorn Royal Thai AFB from 1970 – 1971. The handgun in this display is clearly a replica; it’s not likely that Childers’ issued Model 15 had oversized grips like those.

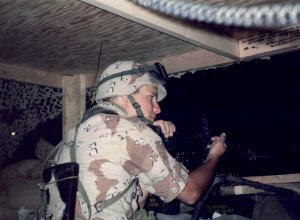

That said, service members tend to get away with more “customization” of their gear in combat zones than at Stateside garrisons. They wouldn’t let me dress Lt Gorman in ergonomic rubber grips when I worked the main gate in Wyoming, but nobody objected to the non-issue 3-point H&K sling I used on my rifle in Saudi, during Desert Storm.

Again, the military is often a decade or two behind with tactical gear and training. H&K’s 3-point slings were state of the art in the 1980s, but most serious users had dismissed 3-points as overly complicated and moved on to adjustable 2-point slings in the early 21st Century. About then, of course, USAF began DEMANDING that 3-points be issued on the rifles of deploying airmen.

So it’s not beyond the realm of possibility that A1C Childers’ folks had sent him a nicer set of grips for Christmas.

The swivel probably made it difficult to get a consistent draw. Most tied the bottom of their pivoting USAF issue holster to their thigh with a boot lace, leather thong, 550 cord, or other string. This helped it pivot forward when sitting down, and probably helped with the draw as well. My GUU-1/P does not have a hole in the bottom for a thigh strap (or for letting water out during a SE Asian monsoon).

“I personally wore my pistol and ammo on a holster belt, and this was strapped on next [after donning the G-suit] and lashed to my right leg with rawhide to be sure it stayed out of the way.”

–Col. Jack Broughton, F-105 pilot, in Thud Ridge, p. 64

This arrangement didn’t always work out. USAF Raven Jim Hix had his .38 in “a tie down holster,” but when he ejected from his T-28, the gun and holster got hung up on a canopy rail and both sheared away. His spirits fell as he realized he was floating down over hostile territory without a sidearm. (The Ravens: The Men Who Flew in America’s Secret War in Laos, p. 318)

When I worked at base entry control points in ’86 and ’87, our issued holsters were the Bill Jordan type. Instead of a wire clip, ours had a leather flap that formed a loop over the belt, giving them a mid- to low-ride (not nearly as low as the ‘Nam era swivel holsters above).

Our Jordans did not have a swivel in the middle, for which I was grateful. I worked mostly at the base entry control points, and did not spend most of the time riding around in a dark blue Chrysler K-car like the LE patrols did. I worked on my feet.

Our issued holster had a cutout for the trigger, which was ridiculous; there is no reason to put your finger on the trigger before the gun has cleared leather and the muzzle has rotated to downrange–especially not if the holster didn’t pivot, as its predecessor the GUU-1/P had.

It was not widely understood in those days that placing one’s finger on the trigger took only a fraction of a second and should be saved until gun is pointed at the threat and you have made a conscious decision to shoot. Or should I say, it was becoming known among civilian professionals as schools like Gunsite and Chapman Academy and Lethal Force Intitute and Yavapai Firearms Academy began spreading the Gospel of the 4 Rules of Firearms Safety (#3 is Keep your finger off the trigger, indexed up along side the frame, until the gun is pointed at the target, and you have made a conscious decision to fire).

Since there were no prohibitions against putting your finger on the trigger (even while drawing from the leather), and it was widely assumed that you would anyway, perhaps the cutout was deemed to be a time-saving measure. Obviously, if you are lifting the gun out of the holster with all four fingers, instead of only the bottom three, you could hear a loud noise and feel a burning, stinging sensation in your holder side thigh and / or calf. Thankfully, we have evolved past that type of dangerous gun handling. Refer to Rule 3: You’ve come a long way, baby for more.

A holster with a trigger finger cutout is actually safer during reholstering. Most negligent discharges with handguns on firing ranges occur when the gun is going back into the holster. The operator forgets to pull his or her finger off the trigger, and shoves the gun in as if the first one back in the holster wins. The finger hangs up on the mouth of the holster while the operator shoves down on the butt. Wedged against the finger, or sometimes a piece of shirt hung up in there, the trigger stays in the same place while the gun moves forward–

–Bang!

But then, many if not most police duty revolver holsters, even in the 1980s, did not cover the trigger at all.

My Jordan holster was stamped on the back with the NSN, NATO stock number, 1095-00-480-6807, over B07-44Y. No manufacturer was listed on mine.

In 1965, when straps as were found on the GUU-1/P holster were also found on most police duty holsters (before thumb breaks became in vogue), famed pistolero Bill Jordan wrote:

“Most officers normally carry the weapon with the strap over the hammer, removing it only when they feel that quick action might be imminent. This process should be reversed, and the gun snapped in only if strenuous action–running, crawling, climbing a boxcar, etc.,–is anticipated.”

—No Second Place Winner, pp. 25 – 26

Jordan preferred duty holsters that had a snap on the back side that the strap could be secured to when not retaining the gun in the holster, which in Jordan’s world was most of the time. When Bill Jordan was on duty, he considered the snugness of a well fitted holster as retention enough for most of his social work. Which is OK as long as the holster retains its friction grip. One downside of leather is that it wears eventually–some makers sooner than others. I have seen an H&K USP-C fly out of a worn open topped holster from just running around on the range. Not really dangerous, with firing pin catches and such, but hard on the sights and the finish and worst of all embarrassing.

I, too, climbed into a lot of box cars in the Patrulla Fronteriza, but at 5’4″ it was more gymnastic for me than it probably was for six and a half foot tall Bill Jordan. The obstacle course at the FLETC Border Patrol Academy even had an obstacle that was the same height as jumping into, crossing through, and then jumping out the other side of a railroad box car. By the time I was chasing smugglers around rail yards, though, the Patrol had cashed in their revolvers for .40 caliber Beretta 96D Centurions in holsters with thumb break snaps.

In the Air Force of the late 1980s, even unsnapping the strap was considered an elevated use of force, so I trained to unsnap it as part of the draw. I unsnapped the strap with the base of my thumb, sliding my palm up the holster before establishing a grip on the handgun. A pain in the bum, to be sure, but I got used to it.

A consistent grip, which is critical in a proper presentation (draw), was difficult to obtain with those wooden stocks, not to mention the leather next to the grip getting in the way. More modern, higher riding holsters have a “jacket slot,” partially to tuck your jacket into, but also to get the grip of the handgun a little ways out from you, so you can squeeze your thumb in there to establish a proper grip in the holster.

I got in the habit of hooking my pinkie under the bottom of the grip. It was not comfortable and gave me less control over recoil, but it did make for a consistent placement of my hand on the grip, and for trigger pull in line with my forearm. Recoil control was not a huge issue during qualifications anyway, as the courses were more about shooting a small group at distance with generous time limits than they were about getting multiple hits on an assailant in a hurry. Regardless, I compensated for the lack of gun-hand control with my support hand, using a Weaver stance.

The USAF was still teaching Isosceles. When I asked my combat arms instructor if I could use a Weaver stance during qualification fire on 28 Aug 1986, she didn’t even know what that was. Two years later, the Air Force adopted Jeff Cooper’s Modern Technique of the Pistol, including its Weaver stance. The Modern Technique remained the USAF’s official handgun doctrine well into this century; refer to Grip, Hold and Stance for details.

I addition to unsnapping the strap, the Air Force considered it an elevated level of force to even place your hand on the grip of the weapon. We were (quite stupidly) instructed that we were not to pull the pistol until it was necessary to shoot it, more than three years after Dennis Tueller published his landmark article “How Close is TOO Close?” And six years after Street Survival was published, citing instances where having the gun out already not only kept the cop alive but often upped the ante till the armed bad guy surrendered without bloodshed.

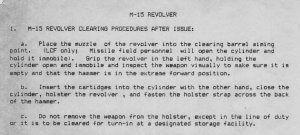

In this set of procedures for the “M-15” revolver, printed on tractor paper in a dot-matrix printer, the third section states: “Do not remove the weapon from the holster, except in the line of duty or it is to be cleared for turn-in at a designated storage facility.” That phrase “in the line of duty” was somewhat narrowly defined by most of our supervisors and trainers.

So, in accordance with USAF policy, I did not point Lt Gorman at the suspect during my first felony bust . . .

First Felony Collar

At Guardmount (the USAF Security Police equivalent of Muster or Roll-call) on 02 Dec 1986, they told us to Be On the LookOut (BOLO) for a canary yellow Pontiac Sunbird.

One had gone missing from a local car rental agency, shortly after an airman had returned it.

Apparently it was a common (but not too bright) scam to rent a car, copy the key, return the car to the rental agency, and then come back later to boost it. How anybody expected to get away with that in a small town like Cheyenne, Wyoming, I’m not sure, but we only catch the stupid ones.

I don’t have much mental capacity; I can only “multi task” on non-multiple tasks. I wasn’t even sure what a Sunbird looked like, but a canary yellow Pontiac I could remember, and I had little else to do while checking IDs and waiving traffic.

About midnight, while I was working in the traffic lane, a yellow Pontiac Sunbird rolled up to the gate. I stopped him, radioed the LE desk, had them verify that the plate was our missing rental, and that the BOLO was still active.

As I said, because of stupid USAF policy, I did not draw Gorman and point it at him. Had he freaked, and come out shooting, he would have had the drop on me. I just asked him to step out of the car, and he complied. As salty trainers tell peace officer basics at law enforcement academies,

“Fortunate outcomes reinforce poor tactics.”

A1C “Woody” Woodhall backed me up, and took over traffic while I escorted the suspect into the visitor center to await LE transport to the base cop shop.

Woody served with me on the Olympic Arena team (see Getting Iron for the Bullhorn god), before separating from the AF and going to work on Pittsburg PD’s Team 5. Since retiring from PPD, he’s been working patrol in a bedroom community.

Woody is still about as fit as he was back then (I’m not). These days, Woody packs a SIG P229 instead of a Smith Model 15. He doesn’t share my nostalgic crush on that old wooden handled wheel gun.

Woody and I have put cuffs on a few other bad guys in the ensuing decades, some not nearly so anti-climactic as the detention of that GTA suspect. But you never forget your first felony bust.

Or your partners.

Spare Ammunition

In the SPs, we were issued 18 rounds of .38 Special: six in the gun, and two six-round reloads we kept in dump pouches on our belts. The dual dump pouch I was issued in 1986 was stamped on the back:

REVOLVER AMMO CASE

62B4016

1095-00-491-8487

OKLAHOMA LEATHER PRODUCTS INC.

F09603-82-C-3824

US

The dual dump pouch Greg G found with the ‘Nam era pivoting holster was stamped on the back:

HOLSTER ASSEMBLY

GUU-1/P

1095-819-8591

J. M. BUCHEIMER CO. 1964

AF 09(603) 48707

U. S.

This left-justified stamp was virtually identical to the pivoting holster listed above, including the designation (GUU-1/P) and the stock number (1095-819-8591). The only differences were the year of manufacture and the second to last line, which may be some sort of lot number. This leads me to believe they came from the manufacturer as matched sets (holster and dual pouch) and were intended to be issued as such.

Apparently that had changed by the mid 1980s; my issued “revolver ammo case” had its own designation. Two digits had also been added to the stock number, which was by then a NATO stock number.

Dump pouches were originally designed to do just that: dump 6 loose rounds into the shooter’s hands. This required some fine motor skills. A true pistolero could load the cylinder by hand without dropping the other cartridges in the dirt, but it took practice.

An officer behind cover could extract the two or three empties he (or rarely, she) had just shot at a suspect, and “tac” load individual replacement cartridges into the empty chambers.

Bianchi made “speed strips” for rimmed revolver cases. These protected the primers while holding the cartridges in a relatively flat, concealable, and easy to transport package. Most importantly, the speed strips held the cartridges in line, which made them easy to stuff (up to two at a time) into chambers. A cartridge laden speed strip took up more space in your palm, using grosser (or less fine) motor skills, than a bunch of individual cartridges.

We kept our spares in issued Bianchi #580 Speed Strips. The combination fit into our Oklahoma Leather Products pouches. They came out easily. Regular cartridges in speed strips are too long; they do NOT come out of those dump cases easily when they are in a speed strip. But we were using shorter cartridges.

PGU-12/B

K-frame Smiths like the USAF’s Model 15 were not designed to handle .357 magnum pressures all the time. The Border Patrol, for example, managed to break several of their Smith Model 19s & 66s by firing full house .357 through them during every qualification and practice session (the BP practiced and qualified a LOT). But the Model 15, chambered in .38, could certainly handle higher pressures than the aluminum framed M13s they had previously issued to aircrews.

Saddled with a round-nosed, jacketed projectile for fear of violating Geneva protocols, USAF had the ammo manufacturers shove a 130 grain jacketed round nose projectile deep into the cartridge case. They crimped the case mouth over the ogive (rounded shoulder) of the bullet till only the top 1/3 stuck out, giving the cartridge a stubby, “uncircumcised” appearance.

This literally over-the-top crimping not only compressed the powder charge. It also held tighter to the projectile just a few nanoseconds longer, allowing the pressure to build up more before the bullet broke free and jumped into the barrel. This resulted in much higher (+P or even +P+) pressures, with correspondingly higher bullet velocities.

I don’t know if it was just a happy coincidence that the shorter PGU-12/B cartridges in Speed Strips fit perfectly in those pouches, or if the dump pouches were designed for regular sized cartridges without speed strips. It’s possible that the pouches were specifically designed around the PGU-12/B & Bianchi Speed Strip combo, but I doubt it.

At the ECPs, we carried six PGU-12/Bs in the guns and two zip strips with six rounds each in our pouches, for a total of 18 rounds per gate guard.

We were NOT issued speed loaders.

Speed Loaders

I had gotten quite proficient with speed loaders when I worked at a pistol range from ’84 to ’86. Even after I traded up from “the Sarge” to an auto pistol, I still practiced with “Mortimer,” my girlfriend’s Model 65 Smith. Speed loaders are harder to conceal but our pistols were meant to be seen. We did NOT use speed loaders when we qualified twice a year.

My father had taught me, by example, never to violate regulations or orders–unless it was the right thing to do. Especially if it accomplished the mission more effectively with less loss of life. Never volunteer information, he taught us, but if you’re caught, own it.

When I packed a revolver for the Air Force after 1985, I always kept a few speed loaders with privately purchased hollow points in my jacket pockets. I figured that if the problem were big enough–say, a coordinated attack by multiple terrorists trying to get a vehicle bomb through the gate and into the interior of the base–and I burned through all 18 rounds of my issued round nosed ammo, even the unforgiving Strategic Air Command couldn’t fault me for having prepared logistically ahead of time, on my own dime. A Mercedes truck laden with explosives had rolled into the USMC barracks in Beirut only a few years before.

The FBI’s infamous Miami gun battle, in which an estimated 140 – 150 rounds were exchanged, and agents were gunned down while reloading, was still in very recent memory. It happened on 11 Apr 1986, the day before I reported to the Security Police Academy (see Edmundo & Elizabeth Mireles, FBI Miami Firefight: Five Minutes that Changed the Bureau, p. 133).

I worked swing shift at the gates. One night an OSI special agent came by, telling us to be ready to close the gates on short notice. They were going to do an undercover buy / bust in the BX parking lot. If the bad guy(s) ran for it, we were to lock them in.

SPs carried an “A-Bag” when they went to post. It contained a flak vest, gas mask, and other items that might be necessary if the ThreatCon increased. When the OSI agent left to conduct the buy / bust op, I reached into my bag and started handing out spare ammo to the troops. The ammo had hollow points and was in speed loaders. I taught the ones who weren’t familiar with speed loaders how to use them. I instructed them not to use my ammo unless and until till they had burned through all of their issued ammunition.

Before that night, I had kept it to myself that I carried extra ammo. To err was human, but to forgive was not SAC policy. But I never caught any flak for it.

The buy / bust must’ve gone OK (or not gone at all), because we never got the order to slam the gates, and it did not turn into a scene from Miami Vice.

–George H, TSgt, USAFR (ret)