Carbines vs Rifles

We often hear those in the know referring to ARs as “carbines.” But doesn’t AR stand for Armalite Rifle? What’s the difference?

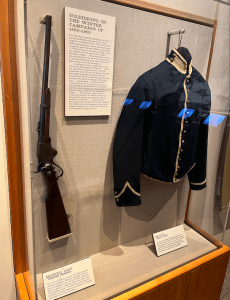

Carbines were originally short rifles issued to cavalry troopers. Troopers generally fought from the saddle with a handgun (or lance, or saber) but used the carbine when they dismounted. The shortness meant less range than a standard infantry rifle, but it was easier to store on a saddle.

In the early days of breech-loaded cartridge weapons, there wasn’t a whole lot of difference between rifle and pistol bullets. Both were fat and round nosed, often with straight walled cases. Pistol cartridges were just a little shorter.

Two revolutions occurred with small arms cartridges near the turn of the 20th Century.

- “Smokeless” powder, enabling much higher velocities and much more consistent velocity (/ accuracy), comes immediately to mind. But equally revolutionary were:

- The smaller diameter, spitzer (pointed), boat tail rifle bullets fired from a shouldered, or “bottlenecked” case. The cases were as wide as their forebears but necked down at the shoulder to put all that smokeless charge behind a smaller faster bullet. These bullets had much less drag. Drag is the rearward force imparted upon a bullet by the air molecules it its path. The pointy tip helped them fly better at supersonic velocities, and their streamlined shape helped them slip through the air with less resistance than their fatter rounder ancestors–like pushing a nail through a stick of butter, rather than smashing the butter with a hammer.

Each side in the Spanish – American War of 1898 had a mix of old and new rifles. Except for a few back-woods guerrillas, all were armed with breechloaders. There were magazine fed, bolt-action repeaters (7mm Mausers and .30-40 Krags) firing faster skinnier bullets, but even the single shot Trapdoor Springfields and Remington Rolling Blocks were much faster to load than muzzle-loading muskets.

Because militaries are often bound by tradition, unhampered by progress, they still did volley fire on occasion, though the accuracy and rapid loading of the rifles had made volley fire unnecessary by the time of the Spanish American war. See the EFK (esoteric firearms knowledge) post about Baron F.W.A.H.F. von Steuben, if you want to understand more about volley fire.

One example (of many): the Lee – Enfield

Although it has several unique features, the manually operated, turn-bolt .303 British Lee-Enfield (SMLE) is typical of this period. It was adopted in 1895, at the end of Queen Victoria’s reign, and versions of it stayed in service with Commonwealth countries till the beginning of Queen Elizabeth II’s. In the 1970s, the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield converted just over a thousand of the SMLEs into sniper rifles (chambered in 7.62 NATO; see below) and the resulting L42A1 stayed in service through the Dhofar Rebellion, the Troubles in Northern Ireland, the Falklands conflict, and the Gulf War.

Within a year of its adoption in 1895, the Brits were issuing a 10″ shorter carbine version of the SMLE to horse cavalry. In the first half of the 20th Century, “carbine” just meant “short rifle”–the cartridge was irrelevant.

The carbine in British service mostly went the way of the horse cavalry (although some were issued to constabularies) till WWII. The Enfield No. 5 Mk I, called the “Jungle Carbine,” came about toward the end of the war and may have seen service in Burma. Later, it was issued to British troops serving in their very successful Malaysian counterinsurgency.

The No. 5 was even shorter than the original Enfield carbines, with lighter furniture, and a flash hider. One problem (of several) with shortening rifle barrels is, the barrel length was originally designed to maximize the interior ballistics of a particular cartridge. In other words, the barrel length is matched to the distance it takes to burn most of the selected cartridge’s powder. When we chop a barrel, some of that powder doesn’t get consumed till after it leaves the barrel. This gives us the double downsides of less bullet velocity, and more muzzle blast (flash and noise).

For a brief, mostly boring but heartfelt anecdote about my first personal experiences with the Enfield Jungle Carbine, visit “Ray” in the Personal Heroes section.

Another example: the Mosin – Nagant

In 1891, the Mosin – Nagant rifles issued to Imperial Russian troops were 51.37″ long, with a 31.6″ barrel. The “dragoon” version, issued to the Czar’s heavy cavalry, was only about 2 1/2 inches shorter, at 48.45″ / 28.8.”

In 1930, while Stalin was working toward his historical achievement of becoming the greatest mass murderer in human history (Mao took first place from him later), the Red Army adopted the Mosin – Nagant 1891/30, virtually identical to the Dragoon (1/10 of an inch shorter) except in a few cosmetics, with a sight graduated in meters rather than arshins. The M1891/30 was the standard Soviet infantry rifle till after WWII, when it was replaced by the Simonov self-loading Carbine (SKS; a Chinese copy of which is pictured at the top of this article), and eventually, the Kalashnikov.

In 1910 and 1938, the Russians adopted carbine versions of the Mosin – Nagant, virtually identical to their predecessors (1891 and 1891/30, respectively) except for a 20″ barrel, making the over-all length of the carbines 40 inches. Their final Mosin – Nagant carbine was the M1944, with a 20.4″ barrel and a permanently affixed, side folding bayonet.

Self Loading Carbines and SMGs

Early (WW I era) experiments with self-loading actions often made use of lower powered cartridges, and led to a distinction between rifles, which fired what we would now call big game (as in elk) type cartridges, and carbines, long guns firing pistol cartridges.

A similar split occurred between machine guns and submachine guns (SMGs), the difference being that the latter fired pistol cartridges.

SMGs were issued to paratroopers and tank riders (Soviet desantniki) in WWII, because they were short & handy in tight spots but could crank out a high volume of fire. If one hit from a 7.62 Tokarev cartridge wouldn’t knock a Nazi down in a room, bunker, or trench, the 5 others that hit him almost simultaneously did.

The Soviets mass produced SMGs in WWII primarily for logistical reasons. Because their SMG cartridge, 7.62x25mm Tokarev, had roughly the same bullet diameter (.307) as the Russian service rifle round, 7.62x54mmR (.310), they could chop a Mosin-Nagant rifle barrel in half to make two SMGs.

While researching a paper for a class called Comparative Development of the US and Soviet Armies in the 20th Century, I interviewed a WWII American paratrooper, and 1st generation Polish immigrant, named Wojtysiak. He carried the Thompson SMG when he jumped into Europe.

The Thompson was not as light as, say, a Grease Gun. Like some other SMGs of the era, the Thompson was almost as long as a carbine. But Mr. Wojtysiak said he preferred the Thompson SMG for fighting in the rooms, alleys, and streets of European towns. It sprayed a lot of bullets and the .45 cartridge was relatively powerful at close range.

SMGs lacked oomph at extended ranges. In the isthmus near Darwin and Goose Green, during the Falklands conflict, 2 Para took machine gun and 35 mm anti-aircraft cannon fire from as far away as 4 – 500 meters. Some British paratroopers swapped their issued L2A3 Sterling SMGs for captured Argentine FALs, which had more reach across the open moors of the Falklands / Malvinas islands (The Lessons of Modern War, Vol III: The [Soviet / ] Afghan and Falklands Conflicts, pp. 283 – 84; The Battle for the Falklands, pp. 244 – 45). The Blokes were already familiar with the FAL, which was identical to the British Army’s standard L1A1 battle rifle in most respects. Perhaps ironically, each side had very similar small arms in that 1982 conflict; see Guns of the Falklands War.

The US M1 carbine (not to be confused with the M1 rifle, the Garand) was an attempt to provide support troops with something light and handy that wouldn’t get in the way of their primary job but could reach out and touch people farther away than an M1911 pistol, Thompson SMG, or M3 Grease Gun.

That M1 was a true carbine, firing a round nosed .30 caliber bullet from a straight walled, 33 millimeter long case (7.62×33 mm; see picture under Intermediate Cartridges) with similar but slightly better ballistics than a .357 pistol cartridge (7.62×33 pushes a 110 grain bullet out of an M1 carbine at about 1990 feet per second). While its listed “effective range” was 300 yards, it will actually hit farther out if you do your part. During the Thunder Ranch Old Rifle course, I witnessed M1 carbine operators hitting steel targets out to 500 and even 600 yards. It didn’t have much punch when it got that far out; the round fat bullet has a lot of wind resistance, and slowed down rapidly.

That said, distinguished firearms instructor and USMC combat veteran Clint Smith’s go-to rifle is an M1 Carbine.

The M1 carbine is light and handy. Clint notes that at typical engagement distances, Soviet 5.45mm won’t penetrate a car door and have anything left on the other side, but that the M1 carbine bullet does. He also notes that SLA Marshall, who studied combat extensively, was not fond of the M1 carbine, but that Medal of Honor recipient Audie Murphy, who was IN combat extensively, liked it well enough.

In his book, To Hell and Back, Murphy frequently mentions using an M1 carbine to dispatch Germans. He also said he preferred the carbine to the Garand for fighting in the woods.

Assault Rifles

For those of you who never read Edward Clinton Ezell’s Great Rifle Controversy, suffice it to say that German research leading up to and including WWII determined that most soldiers on the battlefield did not need an elk cartridge capable of connecting at 900 meters–but they could use something that would reach out to 250 or perhaps 350 meters. They developed a shortened version of the German 8mm Mauser (7.92x57mm), called 8mm kurz (7.92x33mm). 8 kurz had the reach to 350 without excessive muzzle climb on full automatic.

Automatic fire was almost never used, but it was useful (usually in short bursts) to keep enemy heads down while you were storming or “assaulting” enemy positions. A vertical pistol grip helped soldiers fire from rib level while running along next to a tank. Detachable box magazines were handy so you could top off before jumping into the enemy trench or bunker (close combat was the other time automatic fire was useful). To suit those purposes, the Germans invented the sturmgewehr, rifle for storming, or “assault rifle,” with the aforementioned features. The Soviets followed suit with the AK47, and we eventually did with our M16.

In my day we called the M16 a “rifle.” Jeff Cooper called them “mouse guns,” owing to their tiny bullets, but when he was feeling more charitable he referred to them as “carbines” (lest we forget that they didn’t fire more manly cartridges). The name stuck, especially after the GAU-5 / M4 style shorties became commonplace.

Intermediate Cartridges

Like the 7.92×33 (8mm kurz), the other intermediate cartridges could effectively reach where a pistol bullet would not, as far as they needed to (out to 350 or so), but not a great deal farther. Effectively is the key word there, because effective range–where most soldiers can put 50% of their bullets on a non-moving, man-sized target that is not trying to kill them–is NOT the same as maximum range, how far the bullet can travel when fired at an optimum angle up.

Unlike 7.62×33 (.30 carbine), the pointy intermediate cartridge bullets lose less velocity along the way, so they shoot flatter, and hit harder when they get there, than the .30 carbine.

Still, on the receiving end, intermediate cartridges are not as hard-hitting as the typical “big game” cartridges of earlier 20th Century battle rifles. I was always told that the reduced power of intermediate cartridges was intended to injure, rather than to kill, thus removing three enemy combatants from the battlefield (1 wounded + 2 to carry him back to the casualty collection point).

Not true.

That idea implies a level of control over lethality that simply does not exist, and never really has–neither on the battlefield, nor in the minds of military planners.

Any bullet from any cartridge can kill. Or wound. Or miss (most do, under the dynamic, chaotic conditions of a firefight). Penetrating injuries from all projectile launching weapons can have effects ranging from minor to fatal. While some cartridges can deliver more energy to their targets than others, the main determinant of lethality (or not) is where the person is struck and which blood vessels, bone structures, nerves, or vital organs are damaged or destroyed (or not).

Intermediate cartridges do have two genuine advantages over bigger cartridges:

- Intermediate cartridges weigh less, and take up less space. This means soldiers can hump more of them up and down the trail, logisticians can fit more of them on a pallet, and planes and helicopters can airlift more of them to the front.

- Intermediate cartridges have less recoil. That makes them more controllable in fully automatic fire. This is not hugely important, as full auto is rarely used (in Western rifle doctrine), and when it is, it is used in short bursts. Less recoil also makes it easier to train new soldiers how to shoot.

“The great body of our citizens shoot less as time goes on. We should encourage rifle practice among schoolboys, and indeed among all classes, as well as in the military services by every means in our power. Thus, and not otherwise, may we be able to assist in preserving peace in the world . . .. The first step–in the direction of preparation to avert war if possible, and to be fit for war if it should come–is to teach men to shoot!”

–President Theodore Roosevelt, in his last message to Congress

.308: Not Intermediate Enough

The first US attempt at creating an intermediate cartridge, the 7.62x51mm, was merely a shortened .30-06 (7.62x63mm). The advent of ball powder after WWII meant that nearly the same power could be generated in a case with less volume. 7.62×51 kicked and weighed nearly as much as its older brother. Which was just as well, as old-school Army types who did not understand the assault rifle concept, or that logistics are more important than tactics, demanded that our new “intermediate” cartridge must be able to pierce a steel helmet at 500 meters. That most of those using it could not hit a helmet at that distance, much less identify whose army the helmet belonged to, was not considered.

In the US, 7.62x51mm is more commonly called .308, the diameter of its bullet in English units. Other cartridges shoot .308 bullets, though. For example, the .30-06, pronounced “thirty aught six”–the thirty caliber bullet adopted as an official cartridge by the US military in 1906 (“nineteen aught six”). There’s less potential for confusion if we use the more cumbersome convention of naming a cartridge as the diameter of its bullet “by” (written “x”) the length of its case, both in millimeters. Thus, the .30-06 would be 7.62x63mm.

We (the USA) were the main source of supply for NATO, so after we adopted 7.62×51 in the 1950s, other countries followed suit, calling it the “7.62 NATO” cartridge. It is still in use today, in general purpose machine guns (GPMGs), designated marksman rifles, and some sniper rifles. More powerful, flatter shooting, longer range cartridges are available, but 7.62 NATO is not small enough to qualify as an intermediate cartridge.

In modern usage, rifles that shoot 7.62 NATO are just that–rifles–and would not be considered “carbines,” even if they have chopped barrels.

The popularity of rifles firing genuine intermediate cartridges led to a further distinction between “carbines” firing short pointy rifle cartridges, and “pistol caliber carbines” firing fatter, rounder, pistol cartridges.

I often use the terms “rifle” and “carbine” interchangeably, because most of my students shoot 5.56x45mm, 7.62x39mm, or pistol caliber long guns such as the Skorpion redux. Perhaps I should call them two-hand guns, since with the advent of the “brace” they are not so long any more, and are for all practical purposes SBRs (short barreled rifles–US law defining a “rifle” as having a butt stock and a non-smooth bore over 16″) without a tax stamp. Some of my students / RSOs have registered SBRs.

It really doesn’t matter what we call them, as long as everybody understands what we’re talking about. Now you know, if you didn’t already.

Summary

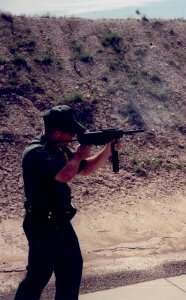

Both of the above have typical “assault rifle” features, including a detachable box magazine, and a pistol grip separate from the stock.

Both of the above have typical “assault rifle” features, including a detachable box magazine, and a pistol grip separate from the stock.

Pop quiz: No, it’s not “Which of the above is a carbine?” Duh, the one on the left is. The question to test your understanding is, WHY? What makes one a carbine and the other not? If you guessed “Size,” you would have been correct in the first half of the 20th Century. In modern usage, though, you’re only partially correct, and not even mostly.

It’s not just size that makes the short barreled AR on the left a carbine, and the longer FN FAL on the right a rifle. The FAL is chambered in 7.62x51mm, a round powerful enough to qualify as an elk cartridge (albeit on the lower end of the “big game” spectrum). The AR on the left is chambered for the diminutive 5.56x45mm cartridge–THAT’s the main reason we call it a “carbine.”

A few of the paragraphs above were excepted from my password protected Alumni post, “RSO Instructor Development, 19 Dec 2020.” I explained it to the RSOs because they will occasionally get that question from their students. “Rifle” and “carbine” are only semantics, but in training, semantics sometimes matter, to get everybody on the same sheet of music.

–George H, Lead Instructor, Heloderm LLC