Ray and the Jungle Carbine

One of the most profound turning points in my education as a rifleman occurred with an Enfield Jungle Carbine, under the tutelage of a Marine I’ll call Ray.

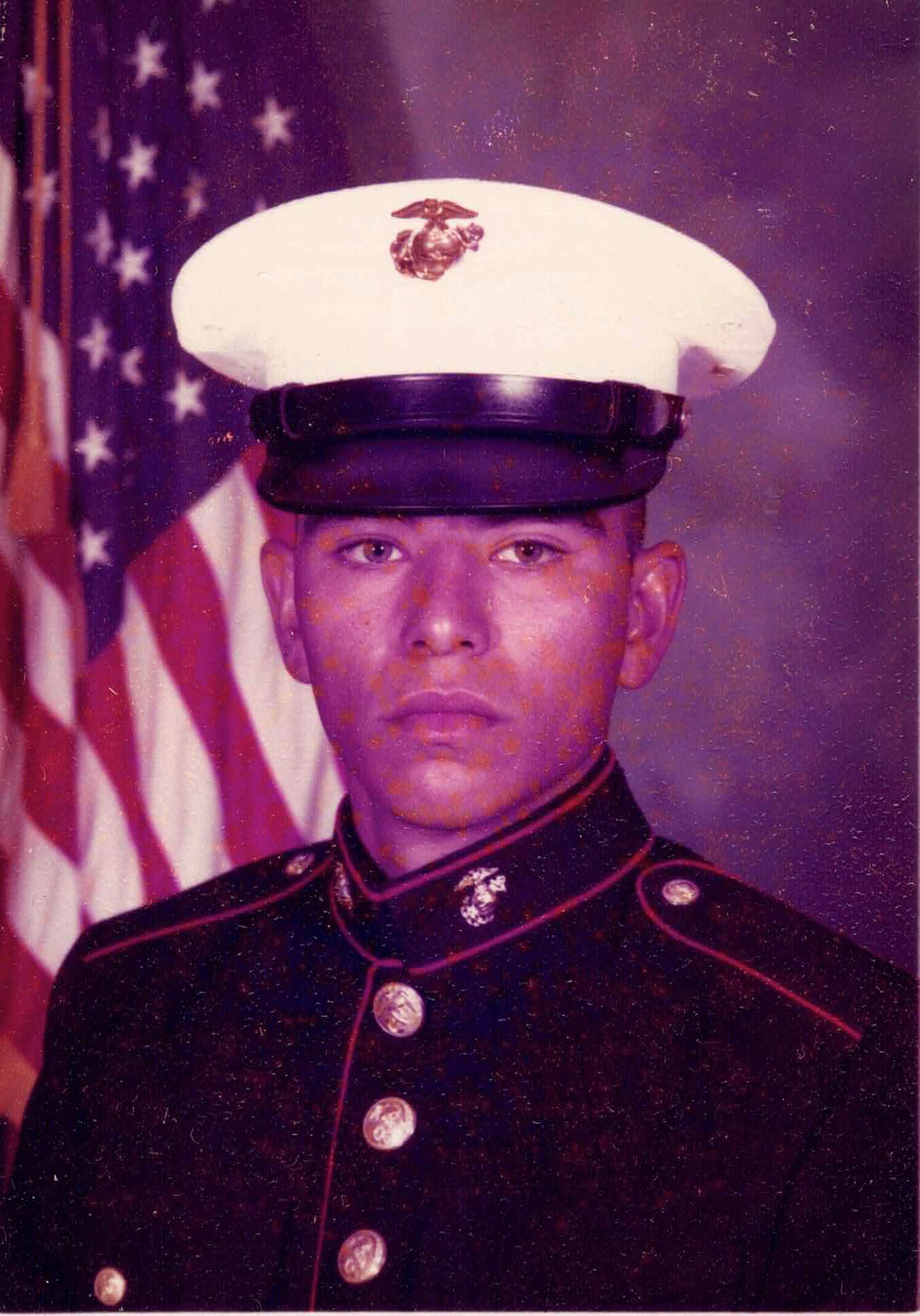

Ray is one of my oldest and closest friends. We’d been team mates in high school gymnastics, though of the two of us, he was the only one with a body to prove it. I was always sleight in stature and build. Ray made it his mission in life to protect me from bullies. He also protected me, throughout my adolescence, from sexually transmitted diseases and teen pregnancies. A ruggedly handsome, smooth operator with glowing cat’s eyes (they’re actually green, although the Kodachrome has faded them to brown in the scanned photo above, which I used to keep on my desk at work), Ray always seemed to be on a direct intercept course with any girl I had designs on.

After high school, Ray joined the USMC Reserves.

I had first shot .22 rifles at Boy Scout Camp Emerald Bay on Catalina Island. I did well enough to get hooked on shooting sports. When I first shot the US Army qualifying course, I only hit half of the 40 pop ups, which ranged in distance from 15 or 25 to 350 meters. Later, I tried out for the USAF Academy small-bore rifle team, but after the lengthy (nine session) try-out process with Remington Model 40Xs and Winchester Model 52s, I didn’t make the final cut.

A friend at the Academy had an Enfield No. 5 Jungle Carbine. I borrowed it when we went on leave, promising to clean it thoroughly before I returned it to the USAFA armory (I wound up finding a gal Ray hadn’t yet beguiled, and completely blew off cleaning it–for which I beg the owner’s forbearance).

I had read about the No. 5 Enfield Carbines. Some sources accused them of having a “wandering zero:” inability to stay sighted in.

We took that Jungle Carbine into the Sonoran desert, along with several other guns. My performance with it was hit and miss. I mentioned No. 5 Enfield’s notorious wandering zero, and blamed that.

Ray picked it up, settled into prone, and proceeded to nail a medium distance target with it, several times in a row.

“When ‘arf of your bullets fly wide in the ditch, don’t call your Martini a cross-eyed old bitch; she’s human as you are–you treat her as sitch, an’ she’ll fight for the young British soldier.”

–Rudyard Kipling, “The Young British Soldier”

Or, as Clint Eastwood said a few years later, in Heartbreak Ridge,

“There’s nothing wrong with that rifle. Keep it tight.”

Ray got me back behind the butt of the Jungle Carbine, and passed on several lessons he’d picked up in Marine Corps boot camp, where rifle marksmanship is still not a lost art.

One problem with chopping down a rifle with a full-power cartridge to make it a carbine, is that the lighter weight makes for greater perceived recoil. It wasn’t an elephant gun, but that carbine kicked more than I was used to. I already knew a little about sight picture and other fundamentals of marksmanship, but somehow what I’d learned on .22s and .223s wan’t translating well to that .303. Most of my problems shooting that Enfield accurately seemed to stem from my anticipation of recoil.

Ray patiently worked me through not any one thing, but several aspects of rifle marksmanship the manuals call the “integrated act of firing.”

The Air Force and the Army, for example, had taught me to focus on the front sight only. Which is not a bad idea, in and of itself. But Ray taught me to look at all three things in turn.

First, the target. Where was that front sight on the target? Start with your sights beside or below the target, rather than on it. Focus hard on the target (if your eyes are still young enough to see it) and slide the front site over it exactly where you need to. Where that is might change depending on distance (hold over or under) or Kentucky windage, especially on older rifles with sights that don’t adjust easily.

Then, Ray said, focus hard on your rear sight. Where, exactly, is the front sight IN that rear sight? With peep sights, most of us simply ignore the rear aperture and assume that our eye will naturally center the front sight in it. Ain’t necessarily so. In fact, our perception of where the center of that peep is changes depending on the distance of our eye from it, which is why a consistent cheek weld is so important (something I learned from Butch Rupert, another excellent rifle coach).

Throw your support hand fingers over the stock between your nose and the rear of the receiver. How may fingers will fit between should be the same every time. With a standard rifle stock, like on the jungle carbine, it could be the width of your whole hand. With AR series rifles (including the M16s and M4s), I put two fingers between my nose and the charging handle; that kept the distance between my eye and the rear peep the same as when I was wearing a gas mask and ran my mask all the up way against the charing handle.

Later, I attended a rifle clinic with Bev Spungen of the Wyoming Army National Guard, first female all-Army rifle champion. Bev shot M16A2s with her nose touching the charging handle, also for consistency.

Those two things, where the front sight is on the target, and where the rear sight is around the front sight, are frequently flubbed with iron sights. Get them right. Then, and only then, pull your hocus HARD to the front sight.

Of course now, most folks have some sort of holographic, illuminated reticle instead. Iron sight expertise is fading from the world. With a “red dot,” even one that isn’t red, try hard to focus on the TARGET, not the reticle.

From that day under Ray’s tutelage on, my rifle marksmanship greatly improved. I wound up representing my base in command-wide rifle competition, and out-scoring all the other rifle shooters in my Security Police Academy class, as well as my small arms instructor (USAF “Combat Arms”) class. I had some great coaches along the way. But I really owe it all to Ray, and that Jungle Carbine, for starting me down the path to success in rifle marksmanship.

Thanks, my friend.

–George H, lead instructor, Heloderm LLC