Slingology

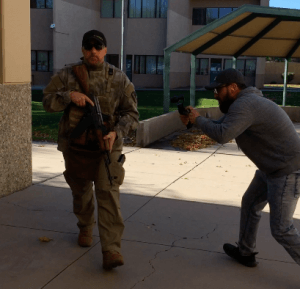

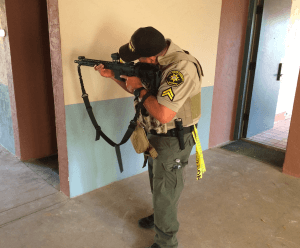

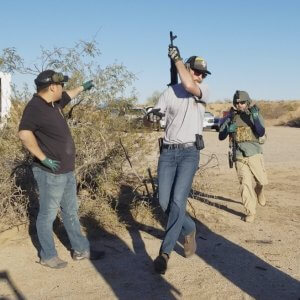

A Ft Huachuca soldier simulates a neck wound while an officer, rifle slung across his back, muzzle down, prepares to apply a pressure dressing, in a Tactical Emergency Casualty Care class.

“Often, we clambered up slopes so steep that guns were slung over shoulders while we clung to the long rattan vines that grew everywhere.”

–John R. White, Bullets and Bolos, a memoir of his years (1901 – 1914) on the Philippine Constabulary, p. 54

In the final analysis, slings are just there so you don’t have to hold a long gun in both hands all the time. They are, as Israeli paratrooper Ian S. says, “the third hand you weren’t born with.” However, somewhat of a tactical cult has grown up around uber cool (and uber expensive) slings and how to use them. “Cross chest” is the new sling arms. But regardless of your sling and carry method, at some point, you’ll need to get your gun off your chest–literally–and back behind you so it’s out of your way when, say, dragging your downed partner, or going hands-on with somebody, or climbing over something.

Before we get into that, here are some terms that everyone who runs a long gun should know, and that will make this article easier to understand. Several are adopted more-or-less verbatim from our Glossary of Gunspeak.

Glossary of Sling-Related Terms

Before we get into these, it’s important to note here that these names, “American,” “African,” “European,” et al, are not handed down from above or definitive. Not every African guide carries in “African” carry. Some Israelis run their sling over the dominant shoulder, rather than in “Israeli Carry.” We use these terms for convenience, so we’ll all be on the same sheet of music when we train.

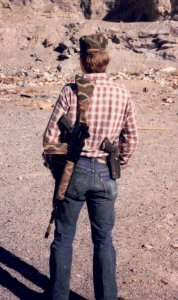

African Carry–One of two preferred ways to sling a long gun behind one shoulder (see Sling Arms) with a two-point sling. In African Carry, the long gun is butt up, muzzle down, behind the SUPPORT SIDE shoulder. It is preferred when it’s rainy, for reasons which should be obvious with a moment’s thought. Of the one-shoulder “sling arms” carries, African is the fastest to engage from, and the least likely to slide off your shoulder accidentally. I believe it was so-called because it is preferred by hunting guides and trackers in the African bush. The Beretta AR70 in this photo is slung in African Carry.

African Carry–One of two preferred ways to sling a long gun behind one shoulder (see Sling Arms) with a two-point sling. In African Carry, the long gun is butt up, muzzle down, behind the SUPPORT SIDE shoulder. It is preferred when it’s rainy, for reasons which should be obvious with a moment’s thought. Of the one-shoulder “sling arms” carries, African is the fastest to engage from, and the least likely to slide off your shoulder accidentally. I believe it was so-called because it is preferred by hunting guides and trackers in the African bush. The Beretta AR70 in this photo is slung in African Carry.

American Carry–The other of two preferred ways to sling a long gun behind one shoulder (Sling Arms) with a two-point sling. When I was in the US military, Sling Arms meant muzzle up carry. If your muzzle is up behind you with the sling across one shoulder only, it should be on the same side as your dominant eye, which is the primary shoulder you should shoot a long gun from, regardless of your handedness, unless field conditions dictate otherwise (in which case you could switch to a Mirror Image hold). Muzzle up behind the dominant side shoulder is called “American” (as opposed to African) Carry, although Aussies, Thais and soldiers of other militaries had hat brims that folded up on one side to make room for a muzzle up rifle. One of several downsides to slinging muzzle up is that it puts a heavy portion of the long gun’s mass over the point where it hooks onto your body, making it more prone to sliding off your shoulder (see below).

Cross-Chest Carry–has the rifle hanging diagonally in front of the operator. The butt is near the dominant side shoulder, while the muzzle points at the ground off to the opposite side. Almost always, the sling is run over the dominant side shoulder and under the support side arm.

Dominant Side–With a rifle, this may or may not correspond to your “handedness.” Instead, it mostly has to do with your dominant eye. For example, if you are right handed but left eye dominant, as my friend and retired Army LtCol Max M is, you might shoot pistol with your right hand but you should primarily shoot long guns left handed.

I say “primarily,” because you may end us switching sides to take advantage of cover or a terrain feature or depending on which way the nearest corner bends. The dominant side is whichever way you are holding the rifle right now. For example, I am right eye dominant. For long guns, in this discussion, my dominant hand, regardless of my actual handedness, will be my right hand. My support side hand will be my left hand. If I am holding the rifle in a left-handed “mirror image” hold to work a corner to my right without exposing myself too much, my left hand might be my dominant side hand while I work that corner, then I will likely switch back.

European Carry–slinging a long gun, muzzle up, in FRONT of your support side shoulder, with the sling strap across that shoulder only.

Although Jeff Cooper saw hunters carrying “European”-style, he’s the only person I knew who did. There’s nothing wrong with European, I suppose. It takes most of the rifle’s weight off your biceps and onto your shoulder, plus European is very quick to get into action should your quarry suddenly appear.

Israeli Carry–Running the sling across your non-dominant shoulder, with the muzzle forward & down, and the butt back behind your armpit. This gets it out of the way, but readily accessible. I don’t think the Israelis invented “Israeli” Carry, and they are probably not be the only ones who carry that way traditionally, but if you look at photos of Israeli soldiers, most of those who are slung up while hanging around (no pun intended) “in the rear with the gear” still sling that way 99% of the time, even during forced marches.

However, Cross-Chest Carry, running the butt-end of the sling strap over the dominant shoulder, the way we see many Tier 1 operators and domestic cops run their slings, seems to be catching on among the rank and file in Israel, as it has in the US over the last 15 years or so.

Long Gun–For the purposes of this discussion, a long gun does not need to be long. It just needs to be designed primarily for use with two hands, as are almost all shotguns, rifles, carbines, and submachine guns. The gun is “long” as opposed to a handgun, which can easily be used with one hand.

Scarf Carry / Neck Carry / Neck Sling–Running the sling behind the neck and across the top of both shoulders. Although supporting the weight of the long gun with your neck gets old in the long run, in short-term tactical situations Neck Carry gives your muzzle more range of motion than any of the under the arm sling carries. Importantly, Neck Carry is also easiest to duck out of, if somebody grabs your gun and tries to sling you around by it.

The Israelis call Neck Carry kley tzavar, or “scarf dress.” When my friend Ian was in the IDF, they would carry in admin mode (Israeli Carry) most of the time, but when they went into battle they turned up their collars, rolled down their sleeves, hung the sling over their neck, and inserted a magazine.

Rifleman–One who carries / uses a rifle for a living. Like Airman and Able Seaman, the term applies to those with two X chromosomes as well as those who do not. “Rifleperson” would just be silly.

Lyudmila Pavlichenco, a very, very capable and accomplished rifleman.

Lyudmila Pavlichenco, a very, very capable and accomplished rifleman.

Shooting Sling–a long gun carry strap, usually connected to the rifle fore and aft (see Sling below), that has a loop you can wrap around the back side of your biceps to help you stabilize your hold.

Sling–A carry strap that you can use to hang a long gun off your body, while freeing your hands to do other things. Some slings can also be used to stabilize your shooting position as an aid to marksmanship (see Shooting Sling above). There are several different types of sling, the primary ones being

- Single point–Only attaches to the long gun in one place. It may hang off a hook on your load bearing gear, or it may wrap over one shoulder and under the opposite armpit in a loop. The single point requires imagination and / or additional equipment to “holster” (get out of your way). Rifles on single points tend to whack the operator in the genitalia or knees when hanging hands free (the real reason Interceptor vests had an optional groin protector). Single points still have some adherents; they might be useful for, say, a medic who may need to take of a first aid pack and put it back on frequently. Single points have largely been supplanted by adjustable two points.

- Two point–Attaches to the long gun in two places, traditionally near the front and near the back of the long gun.

- Three point–Standard issue on H&K’s 2-hand guns in the 1980s, a 3 point sling attaches to the long gun (or SMG) in two places, but then again back to itself, usually in some sort of sliding arrangement, that lets the operator choose an “angle for the dangle”–basically, which way the muzzle points when hands free. It was a revolutionary idea in its time. However, the three point was overly complicated. Running a three point to maximum advantage often took hours of training time, and perhaps an advanced degree in mechanical engineering. In a fight, simpler is usually better.

Sling Arms–One of several ways to hang a long gun off your body with a strap called a sling. In US military marching drill, Sling Arms meant to put the strap (sling) of the rifle over one shoulder, traditionally the right shoulder (regardless of handedness or eye dominance), muzzle up. Although most tacticool operators sling cross-chest, muzzle down these days, there is still a time and a place for one shoulder slinging. Say, you are manning a checkpoint with hours between contacts, and your sling is too short for (or your back is not happy with) cross chest carry. If you choose to sling across one shoulder, muzzle down on the non-dominant side (African Carry) is probably your best option.

The Pros and Cons of Slinghiking

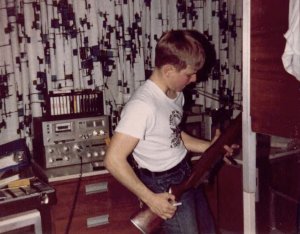

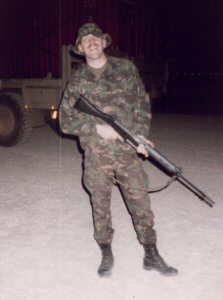

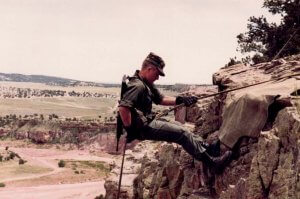

I was a rifleman for most of my adult life–even in school.

The college I went to issued every freshman (we called them fourthclassmen, doolies, or “SMACKs,” for soldiers minus ability, coordination, or knowledge) an M1 Garand. The barrel and chamber had been filled with lead, which prevented the chambering of live ammunition and built character by making the heavy rifle even heavier.

We didn’t use our Garands for much, except to carry around during parades and inspections, or on the Bayonet Assault Course. When we did, the sling had to be adjusted so tight you couldn’t use it for anything anyway. I only loosened the sling after hours, to practice my Pete Townsend full arm circle technique while listening to the Who’s “Won’t Get Fooled Again.”

Seniors at service academies (we called them firsties, for first classmen) got to trade in their rifle for a sword–literally.

But I never made it that far. I washed out of the Blue Zoo mid-way through my second class (junior) year.

After that, I became a rifleman for real, in the USAF Security Police, or SPs.

SPs had three types of duty:

- Walking posts,

- Mobile (riding) patrols, and

- Training.

Depending on which duty you got assigned on that day’s roster, a sling could either be a Godsend or a pain in the ass.

A Pie

Walking posts were also called foot patrol, although you might not be patrolling far. With some walking posts, you just stood there (or sat when you could).

Standing with a loaded rifle for hours on end (or what felt like endless hours) made it handy to have a sling. Clint Smith said the sling is to the rifle as the holster is to the pistol. If frees up your hands to do other stuff. However, if that stuff involved any bending, the rifle often slipped off your shoulder, which is why we learned to go to a muzzle down, cross-back carry when necessary (see below), and why even the tradition bound military eventually switched to cross chest carry for most serious work, even for guard duty.

Vehicle Patrol

Unless you were on convoy duty in Iraq or Honduras, you didn’t generally ride around with your muzzles sticking out of windows like gang bangers doing a drive-by.

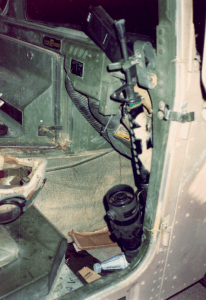

Dedicated military tactical vehicles like the HMMWV had integral clips or mounts for small arms.

Stateside, most of our vehicles were off-the-shelf, fitted with radios and light bars. Most had no provision for weapons, although some had rifle racks in the back window, like a stereotypical redneck pickup truck.

I figured if bullets were flying though the front, back, or side glass, the last thing I’d be wanting to do would be to reach up into that mix to grab my rifle. When driving, I kept mine on the left side of the passenger seat with the muzzle pointed down at the floorboard by the firewall to the engine compartment. My Response Team member kept his or her rifle on the opposite side of the same seat, also pointed at the floor by the fire wall.

I found it interesting that 4 decades later, when I went through “Ambush Alley” at Thunder Ranch in Oregon, Clint Smith also recommended we carry our rifles in the car the same way.

During “15 (troops) in 5 (minutes)” WSA Response Force exercises, I often grabbed my rifle and bailed out of my rig by some cover only to have my rifle ganked back out of my hands halfway through my head-first dive, because the sling got hung up somewhere on the steering column. After a while, I got in the habit of taking the sling off when I worked vehicle posts.

“Unsling those rifles. You’re making too damned much noise.”

–Cling Eastwood as “Gunny Highway,” in Heartbreak Ridge

Training

We trained or exercised a little daily, but I wound up doing combat training much more often than most of our contemporaries because I was on Olympic Arena teams (see Getting Iron for the Bullhorn god).

All afternoon, just about every afternoon, for 6 months out of each year, for several years in a row, we did combat exercises involving protecting nukes from capture by armed terrorists, or recapturing nukes that had been taken by armed terrorists. We did this using MILES, the Multiple Integrated Laser Engagement System. The lasers on our rifles were activated when we fired blank cartridges at the OpFor (opposing forces) role players.

Slings got hung up on the brush and were generally a pain in the butt, but when you needed to drag a “wounded” comrade or help hump the M60 GPMG and its ammo to a better location the sling became invaluable. We had no “QD” (quick detach) technology, so I left my sling on my rifle.

One thing I did do was adjust the sling so it fit snugly under the bottom of an inserted standard capacity (30 round) magazine. As this hooked it under the back corner of the mag, it put pressure on the magazine, tilting it up in front. This helped my M16 to reliably feed M200 blanks, in the days before the M4 came along with its two feed ramps carved into the top of the mag well in the lower receiver. When it was time to switch mags, it was little trouble to pull the sling off to one side.

Slings and Safety

Troops on security duty (such as the Marines guarding the Battalion Landing Team barracks in Beirut, or SPs guarding USAF resources) were, for decades, required to sling off of one shoulder only.

The Army speaks of “risk management.” When an entire division of paratroopers jumps out of airplanes at the same time, the law of averages states that a few of them may be killed or maimed. But they didn’t not train for large operations that might be called for in times of war, just because somebody might get hurt.

Flying planes is an inherently risky occupation, but safety was an obsession in the Air Force, especially in the nuclear-armed Strategic Air Command. They were also optics-conscious way before optics were such a big thing. They avoided even the appearance of being unsafe.

Our rifles were half-loaded (fully charged magazine inserted, nothing in the chamber) while we were on duty. I think one reason muzzle-up (American) carry stuck around for so long was because it LOOKED safer than a muzzle down carry. If the gun suddenly discharged (something I never witnessed), the bullet would go into the air.

I guess the powers that be figured if we carried muzzle down in African Carry, and the gun magically went off, the bullet could strike someone in the foot or ricochet off the concrete. Maybe so, but I’m sure my taller comrades would rather take a bullet from my muzzle (which was below the level of their heads) in the toe, or a frag from a ricochet into the side of their boot, than a bullet up the nose.

Besides, even if it missed everybody on the way up, what goes up must come down eventually. Later in my life, as a duty agent, I once had to investigate a .45 bullet that struck a DHS office window from the outside after hours. It went through the first pane of glass, but not the second in a double-pane insulated window. A hole in the cloth awning above the window revealed that the window had not been the victim of hostile, horizontal, direct fire, but rather of descending “celebratory” fire coming back down off its parabolic arc.

Being shorter than my compatriots, I often got the A-frame of a taller buddy’s M16 in the eye in crowded situations. Once, when my Olympic Arena teammate “Chewie” threw me over his shoulder into fireman’s carry, he slung into American Carry first, and I got his muzzle in teeth.

Call me closed minded, but I couldn’t see how muzzle up was a safer way to sling the rifle.

The only time they officially let us sling muzzle down was if it was wet out.

UNslinging from One-Shoulder Carries

From American Carry

From American Carry

To get your rifle into action from muzzle up off the strong side shoulder, hook your dominant hand in the sling, thumb up. Kick the sling slightly out and away from you with your sling hand, while your support hand reaches under your dominant arm to grasp the hand-guard / fore end of your rifle.

From African Carry

From muzzle down off the support side shoulder, grasp the fore end with your support side hand, thumb down. Point the rifle down range while leaning slightly forward, rolling the rifle sights up as you roll the sling off your shoulder.

From European Carry

Kick the rifle out toward the support side till the sling starts to roll off of your shoulder. Push the muzzle toward the target, bringing the butt around in front of you as you reach across to grasp the small of the stock (or the pistol grip) with your dominant hand.

Lean forward, holding your support hand almost all the way out to make room for the butt to pass in front of your chest as you mount the stock to your dominant shoulder.

Cross Chest Carry

Muzzle Up vs Muzzle Down

In the SPs of the 1980s, we were instructed to carry our rifles at Port Arms when responding to alarms. Again, with the muzzle up thing.

In the 1980s, the USAF taught us to chamber a round, when necessary, with two “snake fang” fingers on our dominant hand, which necessitated letting go of the M16’s pistol grip. These days, if we were right handed and chose a muzzle up hold (Port Arms, or one-handed High Port, say, to wade through a crowd fleeing a security incident) we could manipulate the charging handle by rolling our wrist toward us (putting the gun in the “Work Space”) and using a thumb and forefinger grip on the left side of the charging handle (or reaching over the charging handle if left handed) with our support side hand.

When I responded to alarms at ICBM silos, I carried with the muzzle down, diagonally across my chest, with my right (dominant) forearm across the top of the stock, my index and middle fingers resting on the charging handle–ready to charge a round if necessary. Holding it that way was in direct contravention of USAF port arms policy, but those missile sites were in the middle of nowhere, and nobody was around to see it (now days, they have cameras at the remaining missile sites).

When we were patrolling at Army RECONDO school, we had carried our rifles with the butt near our shoulder, and the rifle diagonally across our chests, with the muzzle down and to the side, the way this Army ROTC cadet is instinctively carrying her rifle, 4 decades later.

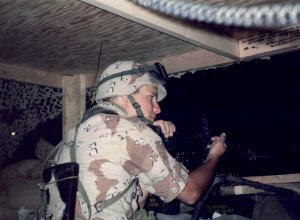

That’s also not unlike the way the Blokes we worked with in Desert Storm carried.

When Clint Smith was in Viet Nam, he noted that radio operators had a very short life expectancy. This was partially because the enemy knew we fought with overwhelming firepower, provided by air support and artillery, and that the radio was the conduit to making that happen. But it was also because that radio antenna bobbed around up in the air like a flag, giving away their position.

To this day, if you take a course from Clint, he will NOT permit you to carry muzzle up, even when near a prone comrade. He and his instructors will have you step around instead.

Cross Chest Slings

Since people were going to carry that way anyway, Heckler and Koch came up with a 3-point sling system that would let the long gun hang off the dominant shoulder with the butt near the shoulder and the muzzle pointing down outside the support side foot. Those had thin, stiff straps and interfaced with a clip on the rifle. The front had a hook that was quick detach and clipped onto an circular eye-bolt on the front of the weapon.

When I deployed to Desert Shield, I ran 550 (parachute) cord from the outsides of my sling swivels over the top of my buttstock and my handguard. I hooked an H&K MP5 sling though it. This would not have passed inspection back in the ‘States, but was considered high-speed, low-drag, and forward leaning when we were off to war.

The MP5 sling was designed to be sling over the dominant side shoulder, but I ran mine over the opposite shoulder and under my dominant arm, so I could sling the rifle around behind me when looking under car seats at a checkpoint, or when manning an M60, or whatever (see Holstering the Long Gun below). I stole this idea from the Israelis, who for years had run a simple sling over the support side shoulder so an Uzi could be tucked under the dominant arm, more or less horizontal.

Eventually, a bunch of companies jumped on the 3-point band wagon. They had various clip arrangements to keep them tight till you wanted them to be loose or whatever. Each succeeding generation became more complex, with nylon sheaths over the clip to keep noise down, or short stretches of bungee cord.

Somebody got smart and realized you could do most of the same things with a two point over the dominant shoulder if you could figure out a way to rapidly adjust the length of the sling strap. Slings had always been adjustable to some limited degree, but they were time consuming and required taking the rifle off. The advent of fasteners that allowed for rapid lengthening or shortening of the sling, yet stayed fixed once adjusted, and did not need to be removed to adjust, was a boon.

Ironically, the same USAF that would have punished me for carrying a three point sling at a Stateside base in the 1980s began demanding three point slings for all deployers in about 2005, about the same time anybody with any sense was ditching their three points in favor of rapidly adjustable two point slings. They also stopped punishing people for carrying cross-chest, muzzle down, and began encouraging it. The Air Force was almost always about a decade or more behind when it came to “ground weapons” doctrine.

Over time, Cross Chest carry became almost a cult, or treated as mandatory, like an 11th Commandment. I’ll give you an example.

During the COVID era, we were filming an Active Shooter Response video. As the armorer for the production, I provided an appropriately “bad guy” looking long gun, a Romanian WASR-10 AK clone with a “Hollywood” slant-brake blank firing adapter. It had a surplus Chinese green nylon sling, affixed to the rifle with short sections of leather that (unlike nylon) would not melt if the gun got fired a lot.

The role player who volunteered to be a “bad guy” was former military. Great guy, volunteering his time to keep others safe, but he simply could not wrap his brain around carrying any other way than Cross Chest with the sling over the dominant side shoulder and under the opposite arm. Which was problematic, because the sling was too short. It was made for Chinese troops who are generally shorter and thinner fore to aft than most Americans, including our role player.

He had forgotten that somehow, American troops had defeated Hitler, and Hirohito, and the Kaiser, and pushed the ChiComs back at the 38th parallel, and had given Charlie as good as they got, holding their rifles in both hands with the slings just hanging down, not slung over their strong side shoulders and around their backs under their dominant arms, with their rifles hanging across their chests.

He was surprised (and I was annoyed) when he broke the cheap Chinese Communist produced leather band that held the sling on, trying to make it do something it was not designed to do.

Transitions from Cross Chest

One huge advantage touted for Cross Chest carry is the ease with which it transitions to pistol when the rifle quits. Instead of stowing the long gun behind the support side arm or at least off to the side, one essentially just drops it to transition to pistol.

When I first became a rifleman, we were not generally dual armed with rifle and pistol. “Transition,” to us, was the first part of “. . . to the rifle as an impact tool” or to stab him with a bayonet or to simply drop the rifle and grab a knife or an E-tool (shovel), if the rifle quit for any reason at close range. Obviously, if you’re gong to beat somebody with your rifle, having it strapped across you is going to limit your range of motion.

When I first became a rifleman, we were not generally dual armed with rifle and pistol. “Transition,” to us, was the first part of “. . . to the rifle as an impact tool” or to stab him with a bayonet or to simply drop the rifle and grab a knife or an E-tool (shovel), if the rifle quit for any reason at close range. Obviously, if you’re gong to beat somebody with your rifle, having it strapped across you is going to limit your range of motion.

At the Border Patrol Academy, they also taught us to simply drop the shotgun when it ran out and to drive on with our Beretta 96D Centurion pistols. We took a knee, set the butt on a pad, and literally dropped it.

Of course, lacking a Cross Chest sling arrangement, one can simply hold the long gun in the support hand and shoot the handgun one handed.

It is also possible, with practice, to quickly turn a hanging sling into strapped across your back. Stick your support arm out in front of you, with the rifle over the top and the sling hanging under. Lift the rifle over your head with your dominant hand, and drop it behind you (see Cross Back carry below).

When practicing transitions by simply dropping the rifle and letting it hang on a Cross Chest sling, run the gun dry to signal your transition. This is safer as the trigger can get hung up on things as you drop it and let it hang by the sling. Some schools I’ve been to insisted that you place the long gun selector on “Safe” before dropping it and letting it hang on the sling, and that may not be a bad idea in training. Just remember that the chances of you remembering to do that when your gun quits in the very near presence of your enemy are pretty slim. If you train enough, placing it on safe might just happen out of force of habit, but is making the gun “safe” a combat skill? We wouldn’t be dropping it in extremis if it was still going bang, so placing it on “safe” doesn’t really make it any safer. It does take time you may not have.

You can make your transition drills surprises by loading all your practice mags with two rounds. Then take a third of them, remove the top round, and place it in another magazine. Set each mag aside when you do (take one or give one). In the end, if you had, say, 6 magazines, two mags should have 1 round, two should have 2 rounds, and two should have 3 rounds. Shoot pairs till you run dry–then transition to pistol. Top off your pistol, holster it, and reset the drill with a different random magazine.

If you have plenty of ammo and time, you can make it more of a surprise by starting with 3 or 4 or 5 rounds or whatever in each magazine.

Downsides of Cross Chest

Cross-Chest can be problematic if the sling is too long, as the rifle may hang down horizontally behind you with the muzzle pointing back toward your friends. This is why adjustable two points are so awesome.

If you are switching shoulders to a Mirror Image (reversed) hold in order to slice the pie around a corner to your dominant side, running the sling under your support side arm can strangle you.

In addition to limiting your range of motion with the rifle, if you’re close enough to beat the bad guy, even with your muzzle, he’s close enough to grab you and sling you around with it, if it’s strapped across your chest.

While a range officer might command “Safe ’em and let ’em hang,” a rifle strapped across you chest is NOT holstered securely from anyone who is close in front of you.

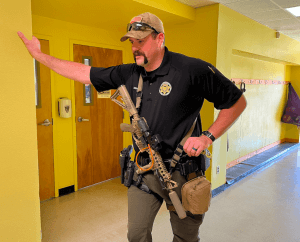

The Cheyenne Incident

Two Cheyenne PD SWAT officers had captured a suspect and were preparing to cuff him. One simply dropped his Cross Chest slung rifle and let it hang from the sling. As they bent the suspect over a couch to cuff him, one of the suspect’s hands found the pistol grip of the rifle dangling around in front of the officer, between him and the suspect. He wiped it off safe and squeezed the trigger, striking an officer in the foot.

Moron. He turned his misdemeanor arrest into felony endangerment at best, and more likely assaulting a police officer. But he sure stuck it to the man.

If you’re going to go hands-on, you need to get the rifle slung around behind you.

Holstering the Long Gun

Cross Back carry

There are times when it’s a good idea to have your rifle slung across your back diagonally, including (but not limited to):

- When you need to go hands-on with somebody (not every bad guy needs to be shot)

- When you need to drag or work on an injured partner

- When you are rappelling

- When you need to cross an obstacle by yourself

If you take a hunter’s safety class, you will learn that it’s safest to hand the rifle to a partner, cross the obstacle, and then have your partner hand you your rifle (and theirs, so they can cross).

Cross-back, muzzle down, keeps it ON your back, and out of the way. Here, for example, over the strong side shoulder kept “Rosa Linda,” my Army issued M16A1 (sn 5322415), out of the way of the rappelling rope.

Here, a student uses cross-back, muzzle down to rescue his partner from a bad guy (the “Jean Luc Picard on Steroids” manikin) in a wrestling match. In the movies, he would simply shoot the bad guy in the back and the bullet would ALWAYS stop in the bad guy. What horse puccy. If your partner is rolling around on the floor with somebody, this is probably not a job for the rifle (unless you chose to use the butt as a club). You might be able to grab the bad guy by the hair (if he has any) and crank his head out of the way to get a clear line of fire for a contact shot with a handgun. That’s why gang bangers so often shave their heads.

If you are fortunate enough to have friends, especially big, hairy friends, you can have one of them go hands-on while you cover, or vice-versa. Whoever is going to get close to the suspect can even hang the sling of his / her long gun over a covering partner’s shoulder while approaching the subject.

Transitioning to Cross Back carry

There are essentially two ways to get your rifle into Cross Back carry when it is slung Cross Chest from a two-point sling:

- Time Permissive (Muzzle Down)

- Hasty (Muzzle Up)

Time Permissive

Ideally, you have a partner covering for you as you get closer to kick the bad guy’s gun or knife farther from him or whatever. If you do, you’ll have time to Swim Out and Swim In.

First, swim your support arm out from the sling on that side. This should leave your rifle sling hanging off your neck (see Neck Sling below). Then simply swim your dominant side arm into the sling and push the rifle around behind you. The muzzle stays pointed at the floor the whole time.

This is safe and effective. Most importantly, the muzzle doesn’t flag everybody in the room.

But the main advantage of muzzle down has to do with the locations of the rifle’s sling attachment points, in relation to the weight distribution of the carbine.

The forward sling attachment is usually (but not always) somewhere along the handguard. The rear attachment point is either at the back of the receiver (near the castle nut of ARs–popular for single points) or toward the rear of the buttstock (more likely with two point slings). The balance point for most carbines is just forward of the magazine well. The heaviest part of the rifle, the barrel, extends beyond the end of the handguard (especially with “M – fourgeries”). This means the barrel of a muzzle up rifle, pulled by gravity, WANTS to fall of the shoulder, while a muzzle down rifle wants to stay there.

I’m here to testify to the stability and effectiveness of a Cross Back Muzzle Down carry.

Once, during an exercise on the Tactical Leadership Decisions course (TLDC) “Thud Ridge” lane, I had played a sniper about 60 feet up in a pine tree (as I recall, it was a Douglas fir).

After a hapless TLDC student got most of his squad killed, I started to climb down. I had the students doing the dead bug while I chewed out their student leader. I had my back to the trunk so I wouldn’t have to berate them over my shoulder. “I hope you don’t screw up like that when you’re my wingman over the Fulda Gap–” I started to say, when I stepped on a portable hand-hold. “–Shit!”

The branch I’d been standing on snapped, and I, having forgotten the climber’s dictum of “always 3 points of contact,” began to fall from about 40 feet up.

I had lettered in gymnastics in HS, and had a fairly well tuned inner ear for three dimensional motion. As I began to fall face first, I could sense my body was going to be head down, just past vertical, when I hit the ground.

I had only one thought, as things seemed to happen in slow motion.

They’re gonna laugh.

I’m gonna face-plant and break my fool neck right in front of these guys I’ve been chewing out, and they’re gonna laugh.

I did not even think about flailing, or grabbing for the branches I was falling through on the way down. I could only think of the face I was going to lose, literally and figuratively. But as I passed between two of the larger, lower branches, my gymnastic training from the rings kicked in subconsciously. I turned my palms outward, grabbing the branches, and tucked my chin, rolling over and finding myself hanging by my hands, with my boots bouncing down to within inches of the ground.

It’s not clear who appeared more startled. The students, their TLDC cadre Don H, or me. The supine students had stopped wiggling their dead bugging limbs and stared at me, stupefied, astonished that I had pulled it out of my butt like that. My M16 was still slung across my back muzzle down, right were it had started, even though I had done a complete 360 degree summersault while crashing through branches, accelerating at 9.8 meters per second squared.

After a long silence, during which the branches eventually stopped bouncing, I let go, landing on my feet like I had planned it. I continued the ass-chewing, as if I hadn’t screamed in a high-pitched, little girl voice on the way down.

“As I was saying, when people’s lives are in your hands, you do not have the option of screwing up . . ..”

Swimming Out and Swimming Into Cross Back Muzzle Down carry does take time.

You may not have much time. If you are moving fast for a reason, and must climb a fence or otherwise negotiate an obstacle, it helps to have both hands free.

Hasty Holster of a Long Gun

This one is not difficult but YOU MUST REMEMBER TO ALWAYS “GO AGAINST THE GRAIN” OF THE TRIGGER. In other words, always move the rifle toward the butt, not toward the muzzle. That way, if the trigger gets hung up on something, it does not go “Bang!”

Likewise, it’s best to practice this with an inert firearm. You can take out the bolt carrier group or at the very least install an empty chamber flag. The muzzle will end up covering half the people in the room, so we must have additional safeguards.

The moves themselves are simple:

- Take your support hand and grasp the handguard over the top, with your thumb on the side closest to your body.

- Let go of the pistol grip with your dominant hand.

- Pass your support side forearm, and the rifle, over your opposite shoulder.

- Tighten the sling as necessary.

This leaves the rifle across your back behind you WITH THE MUZZLE UP, which can be problematic, because the rifle’s center of gravity is up, which makes it want to slip off your shoulder, especially during gymnastic activity.

Here, we were running drills in which the operator had to sling up, cross an obstacle, and then run to a van and shoot through it to rescue a hostage (loading the rifle on the run after clearing the obstacle). Heloderm Coach Nick, who had been exposed to both methods of getting a long gun across his back (see Revolver and AR, 10 Aug 2020), chose to go with the “rapid holster” method of pitching his Kalashnikov, butt first, over his strong side shoulder.

This was faster and easier, but left him with the heaviest part of the rifle up, making it more likely to fall off his shoulder or bean him in the head as he went over the wall. It slipped off his shoulder as he crossed the top.

Not the end of the world, but it can get hung up on the obstacle. It would be embarrassing to try to jump down only to end up hanging by the sling because the rifle got tangled up on the top of the fence or whatever. Everybody must eventually die. Nobody wants to die embarrassed.

Holstering a Long Gun on a Single Point Sling

When a single point is attached to the front of your gear, it’s best to have a quick detach method (I used a simple D-ring / mini ‘biner on my last deployment).

I was capable of slinging it across my back, with the butt up over my shoulder, by swinging the muzzle in an arc over my shoulder and then running the muzzle through a ring for a D-cell flashlight on my belt near the small of my back. This was time consuming at best, and I ended up muzzling my palm as I threaded the barrel into the ring. If I leaned toward the shoulder that the sling ran over, it would sometimes slip off my shoulder. It was imperfect at best. But by that point in my career I had many younger fitter airmen to got hands-on while I supervised with the rifle in my hands, ready to provide lethal cover as necessary.

I ran the single point because I often carried a medic pack and if I used a two-point sling, whichever one I needed to take off first (pack or rifle) would inevitably be under the other.

Many single point sling arrangements are an actual loop of fabric that goes around the operator in a miniature version of a cross chest two point sling. The difference is that instead of connecting to the long gun fore and aft, it only connects at one point. Here Taylor, another Heloderm coach, pushes his carbine on a single point sling back under his support side arm to get across an obstacle.

This got Taylor’s “SBR” / “SMG” sized carbine out of the way far enough for him to scale the wall.

Getting the Long Gun Back in Action: Single Point

As he cleared the top, Taylor paused to swing his carbine back around to his front and leapt off the wall with his primary in hand, ready for action.

I’ve spent much of my life teaching small arms to airedales (airmen). Would that they all were so comfortable and competent with what the USAF calls “ground weapons” as Taylor is. It’s more than just style points. Navy Commander John Byron said:

“A warrior’s instincts make him a student of his craft. The best warriors regard skill with their weapons as high art. However we frequently find two substitutions for this belief in fundamentals: first, the involvement with technical specialization at the expense of personal skill; and second the complacent assumption that the burden of victory rests on the weapon, not it’s wielder. The fact remains that skill with weapons is the essence of the warrior’s craft.”

–Quoted in Tiger McKee’s Book of Two Guns, p. 22

Getting the Long Gun Back in Action: From Muzzle Up Hasty Holster

This is very similar to what you saw Taylor do at the top of the wall. Grasp the stock of the rifle with your support side hand, thumb pointing down. Then bring your thumb around to your front, sticking it–and the stock of the long gun–into your dominant side shoulder pocket.

Again, it’s a good idea to practice this with an inert gun. You WILL muzzle everybody in the room.

Getting the Long Gun Back in Action: From Cross Back Muzzle Down

Is nearly as simple. Simply Swim back out of the sling with your dominant arm, as you bring it around your front, then swim in with your support side arm.

Unless you want to stop half-way through the process and simply hang the gun off your neck.

Scarf Carry / Neck Sling

To reiterate, the primary disadvantages of a Cross Chest sling (i.e., rifle in front of you, sling over your dominant shoulder and under your support side arm) are twofold:

- It limits your ability to traverse the long gun, and

- It makes the long gun into a big Samsonite handle a bad guy can sling you around with.

Both problems can be solved by simply hanging the sling over your neck, instead of hooking the sling under your support side arm.

If it’s hanging over your neck when a bad guy gets control or your long gun, simply duck out from under the sling and drive on with your handgun or knife.

I would not want to hang the gun off of my neck without supporting it with my hands for along period of time. If you’re serving at a roadblock at the entrance to your neighborhood during a period of protracted civil unrest when the police are overwhelmed, and you don’t have the long gun in hand, hanging it off your neck would get old fast.

Likewise, Neck Slinging is not my first choice when climbing over obstacles. This hasty neck sling works here, but cross-back might get that long shotgun out of her way better while climbing this ladder.

I learned about the Neck Sling method from Louis Awerbuck in the early 1990s. I didn’t fully understand its elegant simplicity and effectiveness till it was explained to me by fellow ICSAVE volunteer Ian, formerly of the IDF.

Any more, when I run a long gun standing up, I sling it with a two-point adjustable over my neck alone, unless I’m going to be standing around for a long period of time. Or unless I need to “sling in” to reach out and touch something at distance.

Slings as an Aid to Marksmanship

No discussion of rifle slings is complete without addressing “slinging in.”

One (of several reasons) most people can be more accurate with a long gun than a handgun is because there are more points of contact with the instrument.

Front to back, they are:

- Support side palm to handguard,

- Dominant side palm to pistol grip (or the “neck” of the stock),

- Cheekweld to stock, and

- Butt plate (or pad) to shoulder pocket.

Using a shooting sling adds a fifth point of contact, or at the very least stabilizes the first.

We all know (or should have learned in elementary school) that the triangle is a very stable shape–which is why you see a lot of triangles in bridge construction, for example. Your support arm forms two sides of a triangle supporting the front of the rifle. When you are “slung up” or “wrapped into” the sling, the sling forms the third side of that triangle, which helps to steady your hold.

There are two types of slinging in:

- Deliberate, and

- Hasty.

Deliberate

A Deliberate sling has a split in it that you stick your support side biceps into and then cinch it down. I run one of those on an AR-10 I use as an ASR rifle (see ASR Rifles and ASR Med Kits), in the very unlikely event there is a distant threat harming people beyond the range of typical defensive systems.

With a Deliberate sling, there is a 5th point of contact.

Here, Thunder Ranch Instructor Eric demonstrates a Deliberate sling with a braced (supported) kneeling position.

When I tried out for the USAFA Intercollegiate Rifle team we wore thick leather shooting jackets that had multiple attachment points for Deliberate slings, whether it was for Air Rifle or Rimfire (.22 LR). When the whole kit was properly adjusted, during the natural pause between breaths, the only thing that moved was the bounce of one’s heartbeat.

Hasty Sling

A hasty sling, on the other hand, is simply wrapping your arm though a standard sling in such a way that it steadies your grip upon the rifle. There is a science to it. One can completely relax one’s support side palm, and the rifle will stay right there.

Here Eric demonstrates a Hasty sling, again from a kneeling supported position. A Hasty sling may or may not add a 5th point of contact, but it locks that first point of contact to the rifle like a vise.

I didn’t make the final cut for the USAFA Rifle team, but years later I did represent my base in command wide rifle competitions. We experimented with slinging in, but opted against it because the original M16 “pencil barrels” were not free floated, and so thin that slinging in tightly would actually change the barrel harmonics, and hence, our zeroes.

Many of the AR handguards are free floated these days; if yours is, cranking into the sling should not affect your point of impact downrange. Also, the barrels are thicker and therefore stiffer.

Portions of this article were excerpted from the after action reports for Revolver and AR, 10 Aug 2020, as well as RSO Instructor Development, 19 Dec 2020.

–George H, lead instructor, Heloderm LLC

From American Carry

From American Carry