Norm the Navigator

I wish I’d gotten to know him better, while he was still around.

But then, the same could be said for so many of “the greatest generation.”

What I can tell you is how we met, and what little I learned about him. To really understand that, I have to give you a little background: first about how I was raised, and then about what Norm and his comrades did.

Born and Bred to be a Fighter Jockey

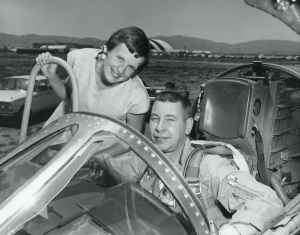

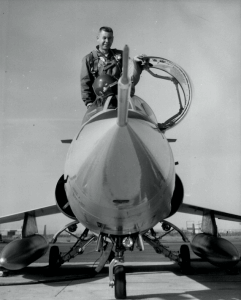

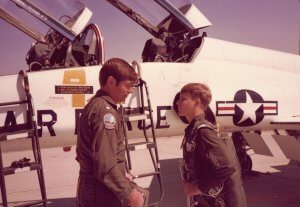

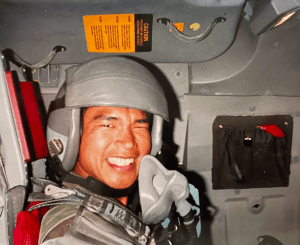

My father flew fighters in three different wars. Between the wars, he was (among other things) a test pilot.

Dad was there, in the hospital, when I was born. I’m the only one of our six siblings who can claim that. For most of us, most of the time, we were lucky if he was in the same hemisphere.

But whether he was home, or a mysterious hero I missed from afar, it’s safe to say I was raised in the cult of the fighter pilot.

Hickam Air Force Base, HI

During the Vietnam War, when my dad was on his first two tours over there, we lived just east of Pearl Harbor, Hawai’i.

Pearl Harbor, of course, had been attacked by fighters and fighter bombers a scant two decades before.

December 7, 1941–and the painful days and years afterward–were still vivid memories for many of those living on O’ahu when we were.

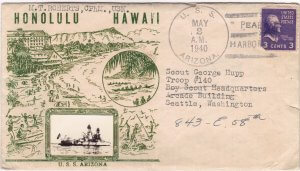

One of our family heirlooms is a letter my dad got from Chief Pharmacist’s Mate McClellan Taylor Roberts, who was a sailor on the USS Arizona. It was postmarked aboard that doomed ship on 02 May 1940. Family lore was that Roberts had been in dad’s Boy Scout troop in Seattle, although the NPS roster of casualties from the Arizona lists M.T. Roberts (there were a few other Roberti who went down with that ship) as being from California. McClellan Roberts was killed, along with 1,176 other crewmen (out of 1,512) when the Arizona exploded.

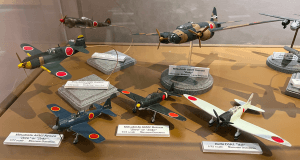

While we were still living on O’ahu, American film company 20th Century Fox and Japanese film company Toei were filming Tora! Tora! Tora! My parents knew some of the pilots flying American T-6s painted up like Japanese aircraft. There were even some genuine Japanese warbirds like the famed “Zero” still flying, although the vast majority of them had been destroyed during the war, or intentionally flown into Allied ships. I remember seeing lots of prop planes with red circles on the wings flying overhead, and watching the movie when it came out.

Aerovac

My mom volunteered for the Red Cross. Aeromedical Evacuation planes on their way from Vietnam (usually via the Philippines) to the ‘States stopped in to refuel at Hickam AFB, Hawai’i. Safety regulations required that those who could get off the plane during refuelling did, but many were too badly wounded to leave their litters. Mom and other Red Cross volunteers would go aboard and give the wounded bed baths, or write letters they’d dictate.

Sometimes, as the spouse of a deployed airman, an essentially single mom, she’d have to take one of her kids with her. Like the time I found one of my older brother’s shaving razors and cut my finger pretty deeply with it. After I got my stitches at the base hospital, it was time for her to meet the plane. I stayed in the lobby of the base Ops building, and did my best to entertain the walking wounded who’d hobbled off the plane to stretch their remaining limbs, by singing songs or doing cartwheels for them. I managed to elicit a few smiles.

By the age of 5 or 6, I knew in no uncertain terms–’cause I’d seen it with my own eyes–that war is no joke, and that soldiers come back mangled from it.

Ironically, two decades later, I wound up as an aeromedical evacuation (aerovac) crew member on National Guard C-130s.

The Hard Corps

In Southeast Asia, my father had been the commander of the 555th “Triple Nickel” fighter squadron, part of Robin Olds’ famed 8th Tactical Fighter Wing (TFW), “the Wolfpack.”

J.D. Covington took this photo of a party “Miss Ruby” Gilmore threw for Robin Olds and Bill Patton in Bangkok, Thailand, on 09 Sep 1968, when the 8th TFW was flying F-4 Phantoms out of Ubon RTAFB. My dad referred to those in this photo as “The Hard Corps.” Here’s what my mom remembered of them:

Back row, left to right:

- Richard G. “Dick” Collins (later a Brigadier General, or B/Gen)

- Red Kimball – 555th Tac Fighter Squadron Commander before my father got to Thailand

- Dad – 555th Tac Fighter Squadron Ops Officer at the time of this photo

- Al Wolverton – Intelligence officer out of San Antonio

- R. Gray – Later what mom called an “A-10 mogul tech rep”

- Kathy Miller – formerly a nurse on Kauai

- George Watts

- Colonel (later B/Gen) John J. Burns – “Our old pal — absolutely great!” said mom

- Colonel (later 4-Star Gen) Chappie James – Vice Commander of the 8th TFW–like Dad, had flown Mustangs in Korea

- Ruby Gilmore – the Wing Commander’s Secretary

- Colonel (later B/Gen) Robin Olds, Commander of the 8th TFW

- Marge “Olive Oyl” Rudolph – the Base Commander’s Secretary

- Whitey Boye

Front Row left to right:

- Bill Poor – a fighter pilot assigned as a Maintenance Officer doing flight test

- Joe Moore (later a Major [2 star] Gen) – His father had been a Lieutenant (3 star) General

- Bill Patton

- Al _____________, – an Intelligence Officer out of San Antonio

- Bill Kirk (later 4-star Gen) – Shot down 2 MiGs, later the Vice Commander of the 49th TFW when my dad was the Wing King

- Estelle Gray – wife of T.R. Gray

- Karl Funk

- Bill McAdoo – Had served with Dad in the 417th TFS, when they’d flown F-86s out of Germany

The Pentagon, DC

Our dad came back from his second tour in SE Asia and got stuck in the Pentagon, an assignment he despised. We moved to Maryland in January, which was a bit of a change from Hawai’i. After about 6 months we moved to Virginia, and stayed there for a few years. Every day Dad drove through DC traffic, past the hippie war protesters, to fly a desk, and read about which of his friends had been shot down the previous day.

Many years later, after I left the Border Patrol to work as a criminal investigator doing ACAP, the Alien Criminal Apprehension Program (which was mostly processing guys just out of jail for deportation), I understood some of my father’s frustration when he had worked at the Pentagon. As Frederick Forsyth wrote in The Dogs of War,

The problem was . . . there was no going back. It was not a matter of getting a job, as a truck driver, a security guard, or some manual job if the worst came to the worst. . . The problem was being able to stick it out. To sit in a dark room under the orders of a wee man in a grey suit, and to look out the window and remember the bush country, the waving palms, the smell of cordite, the grunts of the men hauling the jeeps over the river crossings, the acrid copper-tasting fears before the attack, and the wild, cruel joy of being alive afterward. To remember, and then to go back to the ledgers and the commuter train, that was what was impossible.

But there were some perks to growing up in the DC area. We visited the Smithsonian. We went on tours of the White House and the Capitol Building. Years later, when I was in high school government class in Tucson, I thought “Who doesn’t know this stuff already?” I took it for granted because I’d seen it in person.

We went to Arlington National Cemetery, where we later buried my dad. Being a guard at the Tomb of the Unknowns is grueling–and considered such a high honor, a privilege, that soldiers volunteer for it. If I hadn’t already appreciated the sacrifices our warriors make for us watching the wounded hobble off those Aerovac planes, Arlington would have made it abundantly clear.

A large percentage of our Senators and Representatives used to be combat vets like Dan Inouye. Now very few of them are. They should be required to tour Arlington–it’s right across the river–for several hours before voting on any legislation that puts our boys and girls in harm’s way.

During the three years we spent in DC, we got to watch the USMC drill team spinning their rifles with well practiced precision.

We also toured FBI headquarters. We filed into a gallery behind an indoor shooting range and watched through the plexiglass as a special agent shot tight groups into a target with a submachine gun. Later, they let us onto the range to collect the brass to take to Show and Tell at school.

The Pentagon gig did give dad some time with the family. On my 7th birthday, my father called me into his room and pronounced, “Well, son, you’re seven now. Have you figured out what you want to be when you grow up?” Kids these days are all about work-life balance, mostly life. They talk about what they want to DO. We spoke about what we wanted to BE.

“I dunno, sir. Maybe a scientist, or an astronaut?” It was only a few weeks before Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were going to set foot on the moon. The Apollo program got a lot of air time and news print. The special agent seed had already been planted (or would be in the next year or so) at FBI HQ, but that seed lay dormant for decades.

“Have you ever thought about becoming a fighter pilot?” When I replied that it hadn’t yet crossed my young mind, he planted a different seed. “Why don’t you think about it?” It was phrased as a question, but commanders don’t really make requests. They give orders. I was dismissed.

I had plenty of opportunities to think about it growing up.

When I was a Cub Scout in Virginia, a guy from NASA came and told us of a reusable payload transporter, called a “space shuttle,” that they had planned for several years in the future.

At that Cub Scout pack meeting, I won two movie tickets in a raffle. Dad took me to see The Battle of Britain. It had a little bit of gore, but nowhere near the meaningless violence for its own sake that too many kids see in movies, TV shows, and video games today. It showed the sacrifice of war, and how 1400 fighter pilots literally saved Britain from invasion.

One evening, dad returned from the Pentagon, grinning from ear to ear. He was getting back into the Phantom cockpit. “I’m going back to Thailand,” he announced. “You will be moving to Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico.”

I was happy for him, but a little bummed out because I was going to have to leave my best friend, Barry Rink. Barry’s back yard was catty-corner to ours. We had no fences. When I broke the bad news, Barry was completely unemotional. “You’ll find new friends. I’ll find new friends.” He was right, of course, but it was a pretty mature thing for a 9 year old boy to tell me.

Holloman AFB, NM

We drove our Volkswagen bus up through Pittsburg Pennsylvania–when the steel mills were still cranking–and to Wright Patterson AFB in Ohio, to visit and stay with friends, along our way to New Mexico.

On my 10th birthday, we were at McConnell AFB in Kansas. I remember looking up and seeing the wasp-waisted, lawn-dart looking F-105 “Thuds” flying overhead.

Dad became the Vice Commander of the 49th Tactical Fighter Wing (TFW), under Wing Commander Wayne Whitlatch, while they flew F-4Ds on combat missions out of Thailand.

Napalm

Our elementary school was on base. Our 5th grade teacher was sweet. She was very opposed to the Vietnam War. Her views were a hard sell on us military brats whose fathers were deployed in harm’s way. When a kid’s dad can’t be there for his little league baseball game, and might not come back in one piece or even at all, moms don’t tell the kid that the war dad’s fighting in is objectionable to some members of our overly-protected society. They tell their children that what dad’s doing is very important.

Essential, even.

More important than his baseball game. These days, of course, it might be a dad explaining that what mom is deployed for is more important than any one of us.

Some kids, like me, took an interest in what our parents were doing, and studied as much as we could about it. I had books about the exploits of Medal of Honor recipients and fighter aircraft and fighter pilots. I bought one of them, Gene Gurney’s Flying Aces of World War I, through the Scholastic Book Club at school. I wonder if it would be available to kids these days . . . probably not.

One day our teacher asked us if we knew what napalm was. My hand shot into the air. “It’s jellied gasoline, ma’am. It’s a combination of powdered aluminum, gasoline, and–”

“Do you know what napalm does?” she asked.

“It’s one of the most effective air-to-ground weapons against entrenched personnel. It works when other weapons won’t reach them, like when they’re in a foxhole or bunker or–”

“It sets people on fire!”

“Yes, ma’am, that’s the idea. My father says that if you build a man a fire, he’s only warm for an hour, but if you set him on fire, he’s warm for the rest of his life!”

There was a brief, awkward silence.

“That was a joke, ma’am.”

“Napalm STICKS to people,” she said, the volume and tenor of her voice rising. “It burns little children, like you!”

“Yes, ma’am,” I replied. “But they would grow up to be Commies.”

I remember the sad way my teacher looked at me. As if I was damaged goods.

Children live what they learn. I didn’t see the picture of 9 year old Phan Thi Kim Phuc fleeing Tran Bang after South Vietnamese Air Force bombs fell short, hitting their own soldiers and civilians, till I was older.

Brats Were Different

Growing up on an air base was like living in a very small “company” town. Everybody’s parents worked for the same boss. Everybody knew everything about everybody else–where they lived, what they did, the names of all their kids.

There were differences between us military “brats” and civilians.

I remember that on base, we didn’t lock our doors, but when we were off base, we had to.

Brats tend to speak the jargon of their forebears. To this day, when my sister didn’t get around to something, she says “Sorry, I got behind the power curve on on that.” Most of the people she works with stare at her with blank expressions, as if she’s speaking ancient Greek.

AF bases were not entirely free from racial bias, but they were far more integrated, far sooner, than America’s civilian communities.

Civilians told racist jokes. Poles, referred to as “Polacks,” were usually the brunt of them, for some reason I’ve never been able to fathom. Poles had fought bravely in WWII, against the Nazis and the Russians. The Polish Winged Hussars had driven the Ottoman army from the gates of Vienna (I had a voracious appetite for military history, and was one of the very few American kids that age who had ever even heard of “winged hussars,” before the metal band Sabaton wrote a song about them).

While we were at Holloman I watched the movie Patton in the base theater. The opening scenes were an agglomeration of General Patton’s actual speeches (with the actual General Patton’s profanity toned down a bit for Hollywood censors).

“When you were kids, you all admired the champion marble shooter, the fastest runner, the big league ball player, the toughest boxer. Americans love a winner–and will not tolerate a loser. Americans play to win all the time. I wouldn’t give a hoot in hell for a man who lost, and laughed. That’s why Americans have never lost, and will never lose, a war. Because the very thought of losing is hateful to Americans.”

–George C. Scott, as General George Patton, 1970

The subtext there, of course, explained why it had been so very difficult to extricate ourselves from Southeast Asia. We wouldn’t pull out til the North Vietnamese would at least say they weren’t planning to invade South Vietnam the moment we left, so we could at least tell ourselves that we had held the line, as UN forces had in Korea–even though the “line” wasn’t nearly as clearly demarcated in that murky war (see Appendix II for more).

Perhaps our cultural distaste for losers had something to do with why there were so many “Polack” jokes by European Americans, about other European Americans. If anybody lost WWII, it was the Polish. After being defeated by the Nazis and the Bolsheviks simultaneously, and then by the Nazis entirely, and then by their alleged allies the Red Army, the Poles were still, three decades after WWII, occupied by the Soviets.

It may also have had something to do with the shameful way many Vietnam Vets were treated after the war. The shameful way they were treated during the war was primarily because the hippies believed they were enlightened and morally superior. Their anger at policy makers like Lyndon Johnson was misdirected at those who had little choice but to execute those policies.

TAC & NORAD vs SAC & MAC Rivalry

Within the Department of Defense, there were of course rivalries between the services–most friendly, but some acrimonious. Even within a given service, there were some sibling rivalries.

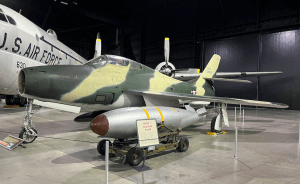

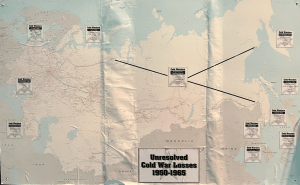

Most Air Force fighter planes were assigned to TAC, the Tactical Air Command. Some interceptors were assigned to NORAD, the North American Aerospace Defense Command, to shoot down Soviet or Chinese or Cuban bombers that might attack the US (see Fighter Interceptors on Alert below).

SAC, the Strategic Air Command, had the bombers and tankers.

MAC, the Military Airlift Command, flew the cargo planes.

On TAC fighter bases, in lieu of “Polack” jokes, we told Navigator jokes.

Fighter pilots poked fun at the navigators, but it was mostly the ribbing that anybody who shares danger gives to their partners. Before 1970 or so, Navs were mostly for the heavies (multi-engine aircraft with large crews) of SAC and MAC (see Two Sets of Eyes below).

I scoffed at anybody who rode anything except a fighter. As a teenager, I got a T-shirt that said “There are two types of aircraft: Fighters and Targets.” I did not know then what I know now, that

You’ve got to be tough to ride the heavies.

I also didn’t realize, till much later, that MAC (later renamed AMC, Air Mobility Command) did more to win wars than TAC and SAC combined. Because, as any serious student of military history can tell you,

Amateurs study tactics. Professionals study logistics.

Logistics like getting fuel to the front, or getting it at all . . . which Norm and his buddies had learned all too well in ’43.

In the 1950s and ’60s, the Strategic Air Command’s bomber fleets (and later, missiles) got most of the USAF’s money. Fighters were considered unimportant and obsolete in the Cold War era of nuclear warfare (as pursuit planes had been viewed in the early 1940s, when strategic bombing was the raison d’etre of the Army Air Forces).

SAC’s motto was “Peace is Our Profession,” and no doubt they kept the peace with the Russkies. See Getting Iron for the Bullhorn god for an inside glimpse of SACs’ contributions.

But when conventional wars like Korea and Vietnam came around, the fighter pilots carried a great deal of the load. In Southeast Asia, the AF world was turned upside down: TAC fighters carried out the strategic bombing of the heavily defended North, while SAC bombers flew tactical air support for ground troops down south (bombers did attack the North near the very end; see Appendix II).

Yes, fighter pilots are a different breed of cat. The true fighter must have that balls-out attitude that immediately makes him somewhat suspect to his superiors. You can’t push for the maximum from your troops, yourself and your equipment and win any popularity contests. You are bound to tangle with nonfighter supervisors and support people up the line who wouldn’t have a job if it were not for the airplane drivers. This they don’t understand in many cases, and fighter pilots don’t know why they don’t understand it. Good fighter pilots move fast, and they do what looks like the thing to do to get the job done. They are prone to ignore the printed word when it conflicts with something real and human and physical. This does not always make them the darlings of all those involved in the defense business, but take a look at the history of aerial warfare and see who is always in there slugging–the fighter guys. War is our profession.

–Col Jack Broughton, Thud Ridge, pp. 92 – 93

I read Thud Ridge, and Michener’s Bridges at Toko Ri, and countless non-fiction books about fighter aces, while I was growing up.

The Pamphlet

While we were at Holloman, my sisters liked to go to a particular book store in nearby Alamogordo. Two doors or so down from the book store was a military recruiting office. I was only ten, but I walked in and checked it out.

Two of the recruiting pamphlets caught my eye, and I took them home with me. One featured paratroopers. The other was about the Air Force Academy.

I looked at that one often. In addition to photos of a gleaming white marble and aluminum university in the mountains, there was a picture of a cadet, a tall young Black man (service academy cadets were all male then) in what I later learned was the parade uniform. The creases in his high white pants were razor sharp. His back was ramrod straight. He wore a high, stiff collared royal blue jacket. But what really got me was his sword.

A sword.

There was a school where you could earn and actually carry a sword if you made it to your senior year.

I was sold on the spot. I wanted to be that guy.

Unforgivable Cruelty

Dad had gotten about halfway through his tour flying into North Vietnam (including Operation Linebacker, I believe), when newer F-111s took the place of their aging Phantoms, and the 49th Tac Fighter Wing rotated back to the ‘States.

One of my 5th grade classmates had a father who’d been shot down and was a POW in Hanoi. If he’d been killed, his family would have had to move off base, but if your dad was MIA or POW you didn’t get uprooted from the community.

One day his son beat me at marbles on the playground, or something. I don’t remember what it was, now, but it seemed very significant at the time. I was very mad at him. We were both out on a hall pass, and I ran into him in the bathroom. I tried to think of the worst way I could hurt his feelings, to get revenge for whatever perceived wrong he had done me. Kids can be cruel to one another, and I was very much so.

“I’ll bet you didn’t even love your dad,” I said.

He picked me up by the collar and held me over a urinal, shoving my back against the pipe. My feet were not touching the ground.

He looked me directly in the eyes. I can’t remember what his face looked like now, but I’ll never forget his cold stare. He didn’t say anything, he just held me there. After some time, not in a yell, not in a whisper, he matter-of-factly told me, “If you had even the slightest idea what you just said, I’d kill you.” He set me down and walked out.

He’d had to grow up fast. I don’t remember ever speaking with him again. There are many, many things I’ve said in my life that I wish I could have un-said, but that one was the worst by far.

I do remember when many of the POWs, including his dad, were repatriated. He and his mom drove with his dad in an open-topped car past our school, while we waved. We’d made “Welcome Back!” signs and held them against the fence.

I felt like a heel, remembering my iniquity–as well I should–but I was very happy for him and his family. Far too many were not so fortunate (see Appendix II).

There Goes the Neighborhood

The Wing Commander and the Vice Commander had identical houses, next to each other, on San Juan Loop at Holloman AFB. In theory, the Vice Commander is an intern studying the current Wing Commander, making lists of what he (or now, she) will do the same, and what they would do differently when they take the reins of command. Unless some character flaw is identified during one’s Vice Commander tenure, or some national crisis arises requiring a shuffling of personnel, the Vice Commander usually takes over as the Commander after a year or two. Thus, the identical houses; for the new Commander’s family, it saves the time and butt-pain of moving next door when the old Wing King moves out and a new Vice moves in.

There was a gate in the fence between our yards. My older brother had a crush on the literal girl next door, and her younger sister hung out with my middle sister.

Other colonels and senior staff lived with their families on San Juan Loop. The base commander, Col Thompson, lived across the street.

I was not doing a good job taking care of my aquarium. The fish kept dying off. Mom said if I couldn’t take care of my pets, I’d have to get rid of them. I decided to give them a better home by selling them on the street, like a lemonade stand, or Lucy giving advice in Peanuts. Mom wasn’t sure I could. Officially, anyone selling anything on base had to be an approved vendor. “Who gives the approvals?” I asked.

“I think the base commander is the final approving authority, although I’m sure he delegates such administrivia.”

I didn’t know what “delegate” or “administrivia” meant, but I knew who the base commander was. I walked across the street and asked him for permission. Col Thompson smiled and said he’d take care of it.

A few days later I got a statement on official letterhead designating me as an approved live fish vendor, signed by the base commander. I kept it with me while I sat behind my folding table with my sign and the bowl of goldfish, but none of the passing SPs stopped to check if an 11 year old was an authorized vendor. If I remember correctly, very few stopped to look at the goldfish, either.

Beth’s Wisdom

My fifth grade crush was Beth Branch, who lived on the corner of San Juan Loop. “I Think I Love You,” and every other Partridge Family song, seemed to have been written specifically about her. When I learned that my dad was going to be the new “Wing King,” I dropped that info into a conversation, attempting to impress her.

“I feel sorry for you,” Beth said.

“Why?” I asked.

“You think you don’t see your dad now? You’ll never see him when he’s the Wing Commander.”

She was right, of course. How did Beth and Barry get so smart at their ages?

When Colonel Whitlatch got promoted to General and moved away, my dad took over as the Commander. Bill Kirk (one of the MiG killers from the Hard Corps photo above), became the Vice Commander and moved his family into the Whitlatch’s old house. Col Kirk’s sons were about my age; one, Kenny, was later a cadet in the class behind mine at the Air Force Academy.

Crashes–a Part of Aircrew Life

Colonel Billingsley, who lived on the other side of San Juan Loop, helped me with a balloon project I was working on.

I was tasked with bringing more firewood from our house to his during the wake, when he was killed in a plane crash. These things were sad but just accepted as part of life for families on airbases.

In March of 1973, while we were at Holloman AFB, at my very first Thunderbirds Airshow, I’d witnessed a different crash. One Phantom had a problem on takeoff. He hit another’s rudder with his nose. The F-4 pitched up violently, rotating around three axes–pitch, yaw, and roll–all at the same time. I was amazed at their ability to fly the plane completely (and obviously) outside of its operating envelope. Till it bashed into the ground and exploded.

Right before it did, we saw parts come flying off the aircraft, as he ejected.

The grace of God alone saved him; the bird was flipping so violently, if he’d stepped out a half-second sooner, he would have come down in the fireball. Any later, and he wouldn’t have had enough altitude for the chute to open.

Crested Cap

The 49th had a rapid deployment commitment to NATO, in the event that the Godless communist hordes stormed through the Fulda Gap in their armor that outnumbered ours something like four to one. Once a year, the entire wing–the largest fighter unit in the Air Force at the time–took off and flew directly to Germany, refueling about 6 times in the air along the way. It was called Exercise Crested Cap (I think because they flew a straight route skirting the arctic ice cap, that looks like a northerly arc on a flat map). Enlisted ground crews and equipment went on C-141s. It was quite a logistical feat, but it must’ve been grueling on the pilots.

Even though I lacked a father’s influence while he was gone, being the Wing King’s brat had its perks. The Wing left for Germany at night. We were driven in a staff car down the parking ramp as the crew chiefs pulled the chocks. To me, the big, ungainly Phantom IIs looked like gigantic bugs about to pounce. Then we parked next to the end of the runway and watched them go, two at a time, with their huge J-79 afterburners searing the night. Modern afterburners are more fuel efficient, with bluer flame. From the Phantom II, especially at night, two slightly down-angled columns of bright yellow flame, easily 20 or 30 feet long, spewed forth.

The noise, even through the shut windows of the car, was awesome. You FELT as much as heard it, in your bones.

In your soul.

I’ve never been much of a motor head. I’m more of a sailing, watching the sunset kind of guy. Nor did I relish the idea of being cooped up in a cramped cockpit for 18 hours, or however long it took them to fly non-stop from New Mexico to Germany. But at any age–especially at eleven–it’s hard not to be impressed by afterburners, or to want to command that kind of raw power by pushing a throttle forward with your left hand.

I knew about how that worked, because on my 11th birthday I’d “flown” one of the wing’s F-4 simulators. It moved on jacks, and was pretty advanced for its day, giving you the feeling of flight, but it was strictly an instrument trainer. The canopy was opaque. There was no visual like you get in virtual reality simulators today. I also “flew” in a T-38 simulator.

On his way back from Crested Cap, Dad always brought us kids Gummy Bears–hard to come by in America at the time–and he brought mom Mosel wine, which she’d developed a taste for when they’d been at Hahn AB, Germany in the ’50s. In my career choice assessments, I counted duty-free imports in the plus column.

I used to hang out at the flightline, just to watch the birds coming in and out. Nobody seemed to mind me being there, or asked where my parents were. I even carried a Kodak Instamatic, and got away with the occasional snapshot. I could have been a 4′ tall Russkie spy, for all they knew, but nobody leaned on my dream by shooing me off.

My oldest brother Brian was very into making, and was particularly good at detail painting, aircraft models. He was fascinated by the chivalry of the WWI aces. If an enemy’s gun jammed, some of them would yell to their disadvantaged foe to meet them over X church steeple the next day, or whatever. When Brian turned 18 and moved out, I inherited his room, and his collection of WWI fighter models which hung by threads from the ceiling. My favorite was Verner Voss’ green Fokker Dr.1 Dreidecker. Brian didn’t just paint it green; he painted it with streaks of olive drab, just like Verner’s. Verner’s signature eyebrows, eyes, and mustache on the front of the engine cowling was a glued-on decal.

I also had a painting of Capt Roy Brown’s Sopwith Camel behind Baron Manfred von Richtofen’s red Dreidecker during their fatal engagement over the Somme.

Instead of a baseball glove, Dad gave me one of those airplanes with a tiny gasoline powered engine that you flew around in circles on a string (way before RC was readily available). When I was older, I got copies of Sun Tsu’s Art of War and Clausewitz’ On War for my birthday. My dad wrote on the fly leaf of Clausewitz,

For our son George Andrew the basic text for a warrior

In 6th grade, we had to do a report about a job we were interested in. Mine was called “My Career as a Fighter Pilot.” I interviewed MiG killer Bill Kirk about his exploits, and told of them in the report.

Edwards AFB, CA

We moved to Edwards, where the Air Force tests planes, so dad could work on the A-10 test program.

Edwards, like most AF bases, was named after a pilot who’d been killed in a crash. The streets in my neighborhood were named after plants (Candlewood, Sage) but “there are streets at Edwards named after golden arms” [pilots good with a stick] “who died trying to tame the F-100.” (Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War, p. 85)

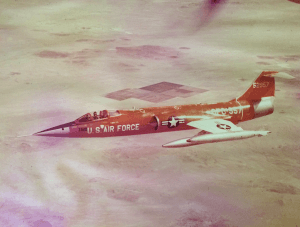

This was our second tour of the Antelope Valley, the high desert of California. Previously we hadn’t lived on Edwards proper, but rather in Lancaster, near Air Force Plant 42, the GOCO (government owned, contractor operated) manufacturing facilities in Palmdale where Lockheed was building F-104s and North American Aviation was making the F-100. It included the “skunk works” where super secret projects like the SR-71 and U-2 were developed.

The Hun

In general construction, the F-100 Super Sabre was like an F-86 Sabre squished flat, with a more powerful, afterburning engine and wings that were swept farther back. Early models (A and C) had no flaps to make the wing more “curved” like a bird (the biological kind) can. Flaps increase both lift and drag at slower speeds, which is why they are used for takeoff and landing.

“The Hun, particularly the A model, was a lieutenant-killer, a widow-maker with a fearsome reputation. One quarter of all the F-100s ever produced were lost in accidents.”

–Robert Coram, Boyd, p. 82

The shape of the wings made the wingtips stall first when the nose was high (that was called a “high angle of attack” relative to the wind coming across the wings–a phrase I learned, along with “transonic buffet” and other fighter-speak, when I was very young). An aircraft is usually designed so that the center of lift, the middle of the lift generated by the wings in their entirety, roughly corresponds with the aircraft’s center of gravity, or CG. The CG is the place it would balance it like a spinning basketball on a Harlem Globetrotter’s fingertip. Engines tend to be heavier than pilots and cockpits, so the CG is often farther back than one might think.

When the wingtips of an F-100 stalled first, that meant that the outermost–but also, importantly, the farthest back–part of the wings was no longer producing lift. The Hun had less lift overall, but the part that still was producing lift was farther forward than the center of gravity. This made the nose pitch even farther up, slowing the bird with the air pushing against the F-100’s flat bottom, and stalling even more of the wing. Pilots would initially try to power their way out of the problem with afterburner, which didn’t necessarily hurt–if the engine didn’t stall–but did nothing to correct the way the wings wanted to tilt up in front, and the way the back end would begin to sashay like a hula dancer.

Eventually, one wingtip would stall more than the other, and the Hun would drop a wing, which the pilot would attempt to correct with the ailerons by rolling the stick left or right (opposite the dropping wing). While the down aileron, on the down wing, gave that wing more lift, the up aileron on the opposite wing would give it less lift. Which was not a problem in and of itself, in fact, it was the intended consequence of rolling the stick left or right. But more lift on one wing also meant more drag on that one wing. And altering the wings’ geometry, specifically the outer (and farthest aft) part of the wings’ geometry, while the outermost / aftmost parts of each wing were stalling, contributed to the stalls in adverse ways. The Hun would not only roll left and right, but it would also yaw left or right, swinging its aft end around like a street racer drifting. Which is fine in as souped-up car on flat pavement. Not so much in a Hun 20 to 30 feet off a runway.

This became known as “the deadly Sabre Dance,” and could result in the bird spiraling in like a Frisbee.

The secret to fighting the Sabre Dance, it was later found (partially through trial and error), was to push the nose over and to use the rudder pedals more than the stick.

Fighter pilots default to controlling roll with left and right motions of the stick. I found out during my first T-38 ride that higher performance, centerline thrust aircraft control their direction more by rolling toward the way they want to go and pulling up (back) on the stick than with the rudder. Rudders are usually more important for coordinating turns with lower powered aircraft (the civil aviation “bug smashers” I’d first learned to fly) and bigger, heavier planes with engines outboard on the wings. But from what I’ve read, the rudder could also be useful with the Hun, to get you out of a jam.

The Bone

The mid-1970s was a heady time to be at Edwards. Most of the aircraft that would be the mainstays of the Air Force for the remainder of the century, and well into the next, were being developed at that time.

When we moved back to the Antelope Valley, Lockheed was still Lockheed, but North American Aviation had become Rockwell. We lived and went to school on Edwards, but we drove over to Rockwell for the “rollout” of the B-1, the first time the first one was made visible to the public. (When I toured those facilities in the early 1980s, Lockheed was cranking out L1011 jumbo jets, and Rockwell was making the space shuttle; I got to walk on a catwalk through the cargo bay of the Atlantis.)

While we were out of school on the winter holiday of 1974, a few days before Christmas, we stepped outside to see the first flight of the B-1, from Air Force Plant 42 in Palmdale to Edwards AFB. The co-pilot on that flight was Col Emil “Ted” Sturmthal, director of the B-1 test project who had also flown the XB-70.

The B-1 looked a lot like a fighter. Mario Campos, who flew in both, said riding in the B-1B was like being in a Cadillac, compared to the B-52, which was like an old pickup truck. But it was still a bomber.

I didn’t want to fly any bomber, no matter how streamlined it was. But I did have a pre-adolescent crush on Col Sturmthal’s adorable brown haired daughter, Robin, who was in my class at Forbes Avenue Junior High School.

I told her how I felt about her at a Halloween costume dance. I can’t remember now where I parked my car 20 minutes before, and I have no idea what costume I was wearing at that dance half a century ago, but I distinctly recall that Robin was dressed as a black cat.

When I suddenly and awkwardly professed my devotion to her, she was taken somewhat by surprise. Robin let me down as gently as her 7th grade social skills allowed.

The Light Weight Day Fighters

Shortly after we moved to Edwards, my family went out to a hangar at night. In it were the YF-16 and the YF-17, two prototypes that were in a side-by-side comparison of capabilities. They let us kids sit in the cockpits.

The YF-16 and YF-17 had been “demo” planes to exhibit what a lightweight “day” fighter with relatively large wings for tight turning in a dogfight might do. It was one of two projects the Air Force didn’t realize it wanted that was forced upon the service, over the objections of many, by John Richard Boyd and his “fighter mafia” (the other was a Stuka-like attack aircraft to provide close air support to troops in contact on the ground: the A-10).

The YF-16 and YF-17 gave validity to Boyd and Tom Christie’s “Energy – Maneuverability Theory.” Later, when I was in high school, an enlisted troop tried to explain to me why bigger heavier jets like the F-14 and F-15 didn’t do “knife fighting” (close-in dogfighting) well, because “specific energy = thrust minus drag divided by weight, all multiplied by velocity.” I found that hard to wrap my brain around. “After the first turn or two, an F-14 loses much of it’s speed, and it’s so heavy it can’t get fast again quickly in a fight.” That I understood.

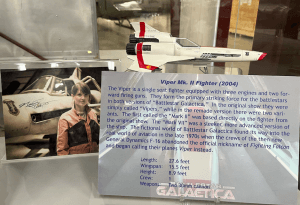

The YF-16 vs YF-17 flyoff became a “fly before buy.” After examining the performance of both, and the potential for developing new technologies with either, the Air Force selected the F-16. The Air Force called it the Fighting Falcon, but after Battlestar Galactica came out a few years later, the pilots called it the Viper.

The Vipers in the TV show were small and quick, like the F-16, but the moniker is a little ironic, since the Galactica was essentially a naval aircraft carrier in space.

My sister babysat–and sometimes dog-sat, for “Duke” Johnston, the fourth pilot ever to fly the YF-16. Duke’s son Mark was in my class at Forbes Avenue Junior High. At parties, Duke played the Eagles’ “Take It To the Limit”–virtually the job description of test pilots–over and over and over.

Are Two Engines Better Than One?

Northrop, who had developed the twin engined YF-17, later sold the plans to McDonnell-Douglas, who put bigger landing gear on it and sold it to the Navy & Marines as the F-18. The Navy only wanted something with twin engines, for safety during takeoffs from carriers, but the reason the F-16 had only one engine was to keep it lighter, so it would turn tighter.

Joe Bill Dryden Sr was another of the YF-16 / YF-17 test pilots. Like my father, he had flown Phantoms in Southeast Asia.

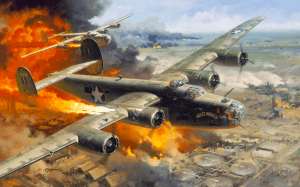

I remember a conversation Joe Bill Sr had with my dad. Joe Bill was describing the F-15 (which was as big as a WWII B-25) as a “flying billboard. You can see it for 30 miles.”

Joe Bill went on to say “those Eagle jocks brag about having twice as many engines, but two engines never saved my ass.”

“Yeah, they did,” my father corrected.

“Hmmn?”

“Don’t you remember that time you were coming off of ___________ ?” [He named a target somewhere in North Vietnam’s Route Package V or VI; I can’t remember the specific location now.] “You got hit and lost an engine and had to recover at NKP” [Nakhon Phanom, an air base in northern Thailand].

Joe Bill thought about it for a moment. “Oh, yeah. But other than that time, two engines never saved my ass . . .”

I was astounded that they had been shot at–and had their aircraft hit–so many times, they couldn’t remember them all. They spoke of it so matter-of-factly, like it was just another day at the office. Which, I suppose, it was.

Joe Bill’s daughter Debbie was in the class behind mine at Forbes. I was attracted to her, not only because of her pretty face, but because of the way she talked. She had a slight southern drawl, but it wasn’t so much how she said it as what she said. She understood some about her father’s work and said things like “tuh-bow fan” and “longitudinal acceluh-ration” and “mach one pont faahve.” I was smitten.

Before my crush on Debbie, I had been in a pre-adolescent “relationship” that crashed and burned. All the cool kids in school were “going steady” with someone, and I wanted to be like them, but I didn’t exactly have the mojo of my Star Trek role model Captain Kirk. For one thing, several of the girls in my school had hit their adolescent growth spurt, but I had not (and would not, until my late teens). I also had no idea what to do, but I asked flaxen-haired Karen Jeglum if she wanted to be my girlfriend.

Karen was pretty smart, which must have been in her genes. Karen’s dad had a PhD in Aeronautical Engineering. Col Paul Myron Jeglum had flown OV-10s in ‘Nam, and wound up directing the Air Launched Cruise Missile program.

My dad, on the other hand, had barely graduated from high school. He joined the Air Corps in ’43, when the hiring standards for pilots were good eyesight, a heart beat, and being able to survive pilot training; according to aviationarchaeology.com, 15,000–15,000!–USAAF personnel were killed in crashes in the United States (mostly in training accidents) during WWII. My dad said the other guys he entered pilot training with were smarter and more athletic, had better eye-hand coordination, and such. Dad got through, he told me, by not making the same mistakes twice.

Grade wise, this apple didn’t fall far from the tree.

Despite the disparity in our IQs, Karen said yes–she would go out with me. But I never actually took her out anywhere. I kissed Karen twice at parties–one of those was on her ear–but neither was that magical, magnetic, first blush of mutual attraction embrace. Rather, they were like airstrikes. I launched at her face from halfway across the room, grabbed her by the head, gave her a quick peck and then dashed away, embarrassed. Eventually, Karen got tired of “dating” a guy who didn’t date, was far from a good kisser, and barely tried to make it to first base. She dumped me, as any self-respecting teen would.

Years later, I was in line at the Air Force Academy BX, and a smiling, blonde lady behind me said “Remember me?” It was Karen, who wound up in the class ahead of mine at USAFA.

Aware of my previous lack of luck with love, my mom and older sisters encouraged me when I said I liked Deb Dryden. They took us to a theatrical play, and to a dance.

If anything, I was even more reserved with Debbie. Too reserved, it turned out. After we walked into the dance, I was so nervous I didn’t know what to do next. I found some guys I knew and hung out with them. I had to laugh years later when I was watching a Harry Potter movie; Harry and his friend took a pair of lovely twins to a dance but then didn’t know what to do and pretty much ignored them, as I had with Deb. What a putz I’d been.

Later, when I came back to Edwards for a T-38 ride, my dad and I dropped in to visit the Drydens. Joe Bill was testing the General Electric F101 engine in the F-16 at the time. Debbie was on her way to work as a lifeguard at the O’club pool, but Joe Bill wasn’t home yet so Debbie, properly raised southern belle that she was, stayed on to entertain us till he got there. She was very gracious to both of us. If she remembered the way I had left her hanging at that junior high school dance, she gave no indication.

Two Sets of Eyes

In the 1950s & ’60s, the target acquisition technology had not yet caught up with the increasing speed of the jets. The century-series fighters had the highest pilot loads (things the pilot had to know and do to keep it in the air) in history. The F-100 was the worst.

“The Hun was one of the most unforgiving airplanes ever built. It had to be flown every second; one wrong control move, one moment of inattention, and the F-100 would “depart flight”; that is, it quit flying and assumed the aeronautical attributes of a brick.”

–Robert Coram, Boyd, p. 82

Computers had not yet taken much of that load off (now, fighter pilots must practically be computer programmers). GPS would not really be a thing until the 1980s.

Jack Broughton wrote of being hit during a strafing run in an F-105. The resultant damage caused high-G left and right oscillations. While flak was bursting around him, and his bird was pointed at the ground at about 500 knots, he had to remember which circuit breaker (of several hundred in the plane) would short out the malfunctioning electrical stability augmentation gear in his damaged tail. Then he had to reach back behind him and locate that particular circuit breaker by feel, and pop it out with his fingertips (Thud Ridge, pp. 241 – 45). All while still flying the plane and getting thrown around left and right in the cockpit.

Some aircraft which normally had one seat got two for special missions. The Misty FACs (F-100Fs) and the Wild Weasel F-105F/Gs had weapons systems officers (WSOs) in the back seat to stay focused on the radar, and operate various additional systems.

The Wild Weasels had a special mission: to take out surface to air missile (SAM) sites after they’d been built. President Johnson would not let our aircrews take out the SAM sites AS they were being built, which any sane warfighter would do, because Russian technical advisors helped the communist North Vietnamese set them up.

Asinine.

No–not asinine. Criminally negligent. Dereliction.

Johnson didn’t want to be the president who started World War III by killing a few Soviet technicians.

He could have told Soviet Premier Kosygin that if Alexei didn’t want his technicians hurt, he should keep them out of war zones, and tell them not to set up SAMs to kill our pilots. Kosygin would likely have ignored that promise and sent them anyway. Vietnam was, after all, a proxy war. But Johnson did not understand the Soviet mindset, their willingness to stoically suck up losses to achieve an objective.

The Russians had killed millions of their own people (estimates run upwards of 20 million) in the run up to, and during, WWII. That number does NOT include the 20 million or so killed by the Nazis. The Red Army marched people across minefields to save their precious tanks. Soviets were heartless, they were atheists, but they were not stupid. They would not have ended all life on the planet over the loss of a few Russian SAM techs, any more than we would have nuked Russia over our (considerably greater) losses in Vietnam. Any president who could not see that was unfit for office.

So only after a SAM site was up, running, and deadly, could our aircrews go after it–and sometimes not even then.

The Wild Weasels played a very dangerous game. They got the SAMs to “paint” them on their radar. Then they would fire a missile that tracked on the radar that was painting them back to the Fan Song fire control van in the middle of the SAM site.

You see the inherent drawback to this plan, don’t you?

It was like standing in the dusty street, facing down the outlaw, waiting for him to “clear leather” before trying to beat him to the punch (which only happened in Western movies, by the way; none of the real cowboys and lawmen of the 1800s were that stupid).

Because the Sam Suppression mission was so dicey, and the new radar hunting technology was so labor intensive, Weasels had a dedicated “scope dope” in the back seat who did nothing but monitor for enemy Fan Song radars and run the weapons systems.

Just flying the planes alone was getting too labor intensive in the ’50s and ’60s. The F-4 Phantom was designed from the start for two pilots. If nothing else, the GIB–“Guy in Back”–was an extra set of eyes that could watch for SAMs, and break his neck “checking 6” (o’clock) for MiGs.

The AF policy, when they first got the F-4, was that both the front seater and the back seater would be qualified pilots. Junior pilots started in back before eventually being moved to the front seat, just as an airline pilot starts as a co-pilot in the right seat.

Air Force Phantoms (Cs and Ds when my dad flew them, later the Es and Gs) had flight controls, including stick, rudder pedals, and throttle, and many of the necessary instruments to fly the plane, in the back seat as well as the front.

The Navy’s F-4B, F-4J, and F-14 did not. The RIO, Radar Intercept Officer, in the back of the F-14 (think “Goose”) was just along for the ride. If for whatever reason the pilot was out of action, the RIO had no option except to bail out. The Navy’s contention was that it would not do to have two people trying to fly the plane at once, which makes some sense.

That’s why, when I was learning to fly in tandem cockpit (one seat behind the other) aircraft, whoever was taking charge of the flying responsibilities would shake the stick (and thus, the aircraft) while saying “My plane”–so everybody knew who was supposed to be driving. Basic CRM (crew resource management).

Sometimes the GIB was the aircraft commander and sometimes he was the mission commander, but it was usually the other way around. There may have been some friction or misunderstandings in the “two pilot days” but I’m unaware of any that led to the loss of an aircraft or mission compromise. The fundamental tenet of CRM is that everybody should focus on their own job, not their crew mate’s. When my dad would discipline us kids growing up, he called it a “roles and missions briefing.”

Toward the end of the Vietnam War, fighter pilots were getting harder to come by. For one thing, the WWII era pilots–of which there had been a great gracious plenty–were mostly retirement eligible by 1965. Just about all fighter pilots in the USAF had rotated into and out of the theater for at least one 100 mission tour. There were many warriors like my dad–Karl Richter comes to mind–who just kept coming back for tour after tour, mission after mission, at least until they wound up dead or captured. Others had been there, done that, got the T-shirt, and were losing interest in getting immolated for what was clearly not appreciated on the home front. They never did it for the recognition, but it was demoralizing when their own leadership did not prosecute the war to win it, or as if their lives even mattered at all. Administrators attempting to fix our current nation-wide shortage of law enforcement officers, which gets worse by the day, could stand to learn this lesson from history.

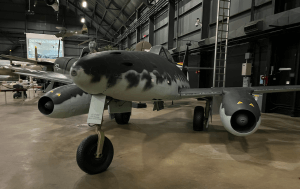

The USAF said it needed more fighter crews to keep their mainstay Phantoms and Thuds manned. Some tanker, bomber, and transport pilots cross-trained into fighter cockpits. B-52 Navs, already accustomed to being “talking baggage,” were pulled to be F-4 WSOs. There was much more light in a glass-canopied fighter cockpit, and many more Gs, than they were used to.

Toward the end of the 1960s or in the early ’70s, SecDef MacNamara decided that new navigators could become Phantom WSOs without prior experience in SAC or MAC.

After initial Nav training at Mather AFB in California, they went to Tactical Navigator, or TAC Nav, school. Then they went to RTU, the replacement training unit, for their specific weapons system (usually the Phantom II). This whole process was still less time consuming and expensive than sending a student pilot through undergraduate pilot training (UPT) and RTU. Pilots in the back seat were officially designated PWSOs; those who came up through the navigator track were simply WSOs.

It got more butts in the back seats faster, cheaper. The hard math–the kind MacNamara excelled at–was, if many of them were going to be cannon fodder anyway, why spend more to train them? Those who survived OJT–on the job training–over North Vietnam were bound to become just as good.

In that (for once), he was right. Nav WSOs may not have been quite as qualified as pilot back seaters on their first missions (studies gauged their combat effectiveness, on average, as slightly lower than PWSOs for up to 30 combat missions or so), but after that there was no appreciable difference.

This mirrored studies of World War II fighter pilots; if they survived their first five combat experiences, they were vastly more likely to survive the remainder. Experience also correlated with combat effectiveness, but did not correlate as well with survival, for bomber crews in WWII. A more experienced pilot might have a better chance of bringing back a damaged plane, but the more combat time he had, the steadier he flew his bird on the bomb run. Flying straight increased your chances of putting your bombs on target, but it also increased your chances of being hit by flak.

Any pilot with any sense gave his back seater flying lessons anyway. There was a very real possibility that the front seater might wind up out of action. I know of one IFE (in flight emergency) where an Air Force Phantom back seater–a Nav–landed the plane and saved the life of the pilot after the front seater had been knocked unconscious by a bird strike.

In 1986, my Civil Air Patrol friend Ray E. Smith Jr became a navigator, and then went on to become a WSO in F-4Gs (which had taken over the Weasel role from the obsolescent Thuds) and eventually in F-15E fighter bombers. Ray had to fly the bomb and fuel laden plane for his front seater when the pilot got spatial disorientation in the dark on the first night of Op Desert Storm. Eventually, the pilot got his inner ears’ equilibrium back on the straight and level. Ray’s intervention at the controls saved their part of the mission and possibly their lives (Strike Eagle, pp. 89 – 90).

Our highest scoring ace in Southeast Asia, with six MiG kills, was actually a Phantom back seater, Capt Charles B. “Chuck” DeBellevue, who started as a navigator. After the war, they sent him to pilot training. It must’ve been weird, being trained by instructor pilots, some of whom may never have seen combat, when he was already a fighter ace with many combat missions and hundreds (or thousands) of flight hours.

Two seats did make planes heavier than single seaters. But Phantom jocks felt lonely without a partner.

My dad had some vinyl record albums by Dick Jonas, a PWSO from the 433 TFS (part of the 8th TFW Wolfpack). Jonas sang a twangy country ode to the F-105s and their drivers. It poked fun at both in an admiring way.

I love my Thud; it is my plane

It is my body; I am its brain

My Thunderchief loves me, and I love her too

But I get the creeps with only one seat, and one engine too . . .

By the time I was learning Navigator jokes, Navs had been part of the fighter community for years. But pilots still poked fun at them. Navs told pilot jokes, too. I recall one about pilots wearing great big watches, to make up for other inadequacies. But I wanted to be in the front seat, or the only seat. I actually thought (as did those who promoted people to the highest ranks in the Air Force in those days) that those who were not “rated” as pilots were somehow lesser mortals.

Higher Faster: The F-104 Starfighter

The single seat A-10 was pretty much the polar opposite of the Starfighters my dad had tested when we lived in California the first time. The F-104 had been sleek and fast, the very definition of “high speed, low drag.”

The Starfighter had thin, stubby, trapezoidal wings. You could cut steak on the leading edges. The wings had so little camber (the rise in the top surface that generates lift), exhaust from the engine was blown through small slots across the top of the wings to keep the air from tumbling over the top (stalling) when it had to slow to only a couple hundred miles an hour for landings. The ‘104 was one of the first aircraft with such “boundary layer control.”

You don’t take a Formula 1 racer to the store for groceries. Similarly, the Starfighter was never meant to fly slow. Nothing in the world could out-turn it supersonic, but unless it was going really fast those wings could barely hold it in the air. They were more like fins on a rocket. People called it the “manned missile.” The pilots called it “the Zipper.”

Thus, a dead-stick landing (gliding in after the engine flamed out, without boundary layer control) required a steep approach angle and great skill. Only a handful of pilots–including my dad and Bernie Fisher, who later earned the Medal of Honor in an A-1 Skyraider at A Shau, Vietnam–have ever attempted to dead stick a ‘104, and lived to tell the tale.

Although he was the first to log 1000 hours in them, my dad was not among the very first to fly the Zipper. Lockheed kept a list of Air Force pilots (not including company test pilots) to join what it called “The Order of the Starfighter,” those who had flown the Manned Missile, more or less in order. About a hundred test and operational pilots were ahead of my dad in The Order. Several of them, like Chuck Yeager (number One in The Order), were quite distinguished stick and rudder men.

But the ‘104, like the Hun, was very unforgiving, and many of them, like the redoubtable Korean War fighter ace and X-2 test pilot Iven Kincheloe (number 24 in The Order), perished flying the Starfighter. My mom buried three–count ’em, three–pilots from separate Starfighter accidents on one day. I think she said it was a Saturday. Mom said she kept her stoic supportive pilot spouse face on throughout the first two funerals, but when the third missing man formation flew by, she broke down and cried.

Being an “acceptance” test pilot–Dad would take them off the assembly line for their first flight and check them out before the Air Force accepted them into its inventory–he got to log more hours in the airframe, faster, than most operational interceptor pilots.

Low and Slow

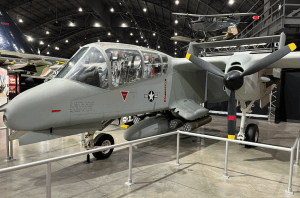

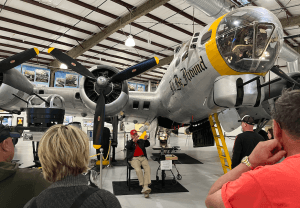

The A-10, on the other hand, was low-speed, high drag. It had straight Fokker type wings. I believe it was the first retractable gear aircraft the AF had procured since the WWII B-17 and C-47 in which the wheels of the main landing gear didn’t even go all the way into the airplane.

The A-10, officially named the “Thunderbolt II,” is an incredible aircraft, purpose built for war. Like the P-47 Thunderbolt it was named after, the A-10 had numerous features designed to make it more survivable in combat.

Pretty, the A-10 was not. For that reason, nobody who flew it or worked on it referred to it a Thunderbolt. They called the A-10 the Warthog, or simply, the ‘Hog.

The A-10 was controversial when it was developed, but hundreds if not thousands of American soldiers now owe their lives to the Hog. I have met infantrymen who called that ugly airplane the prettiest sight they ever saw.

A-7 pilots in the Tucson Air Guard (the 162nd TFG) were admonished to be nice to A-10 pilots they might meet at the O-club at Davis-Monthan AFB, because Hog jockeys were the only ones who flew something slower and uglier than the A-7. They called the A-7 the SLUF, for Short Little Ugly, uh, Fellah.

The A-10 deserves its own article. Suffice it to say that it was much slower and lower powered than what my dad was used to. After he flew it for the first time, my mom asked him how he liked it. “Well, the good news is, it can take a lot of hits,” he said. “The bad news is, it’s gonna.”

Columns of Smoke

Just about every air base had a pit with an old, burned up aircraft, or a welded-together sheet metal facsimile of an aircraft, sitting in the middle. Periodically, the fire / crash / rescue folks would fill the pit with jet fuel, spark it off, and then practice foam-hosing a path to it and ganking out the melted crew manikin(s). Pretty early on, Air Force brats learned where the crash rescue pit was at their base. We would periodically see a column of thick black smoke rising from it.

When a column of thick black smoke rose from another part of Edwards Air Force Base, we knew what that was, too.

Edwards had a supersonic corridor just north of it. From time to time sonic booms would rattle our windows. Every once in a while, you could hear and see columns of flame from Rocket Ridge, where they tested space boosters.

Triple Four Yankee

While we were at Edwards we had a time-share in a general aviation (civilian bug smasher) aircraft, a butterfly tail Bonanza. It was the first plane I ever had my hands on the controls of in flight, over Bakersfield, CA. When Dad flared out for a landing, he was so smooth, you felt the rubberized filler pushing up between the sections of concrete–bump, bump, bump–before the wheels touched the runway.

Rocket Man

While we were at Edwards, they were also testing the F-15. They were setting time-to-climb records with the Eagle, which had more thrust than it weighed. I remember being on the soccer fields of Forbes Avenue Jr High, and hearing a roar. Looking up, I saw an F-15 completely vertical. It kept accelerating as it went up (the Eagle could beat a Saturn V to 30,000 feet or so). Eventually, it was barely visible. I would’ve lost track of it, but it got so high up it started pulling a completely vertical contrail.

Again, I wanted to be that guy.

Later, when I was a cadet on my first T-38 ride, the pilot said, “OK, hit the burner and crank the nose up about 30 degrees.” I felt like Luke Skywalker in his X-wing. Looking down, I thought of some kid who might be on a soccer field looking up at us. That’s right, I thought. Hear MY noise.

Davis-Monthan AFB, AZ

Dad brought the A-10 to Davis-Monthan AFB in Tucson, Arizona in 1976, for its initial operational test and evaluation (IOT&E). We lived off base for the first time in years.

Sam Nelson, A-10 Test Pilot

My godparents were Howard “Sam” Nelson and his lovely wife Jackie. Though he was not a relative by blood or marriage, we called him “Uncle” Sam (we had several “Air Force uncles”). He’d gotten out of the Air Force and was a test pilot for Fairchild, the company that made the A-10. When I was in Jr High, I sent a fighter design to Fairchild for evaluation. They no doubt got some amusement from my crude drawings. When I didn’t hear back, Uncle Sam told me that sometimes hypersonic jet proposals are evaluated by men who move at the pace of arthritic snails.

In June of 1977, my mom got a call from the wives’ network. We turned on the TV to see Sam crash an A-10 (while Jackie watched) at the Paris Airshow. He was killed, but not right away. The titanium bathtub that surrounded the cockpit to protect the pilots from Soviet 23mm protected most of his body when the bird hit tail first and flipped. It was only his top 1/3 that got crushed. We found out later that he actually got to say goodbye to Jackie, and died literally in her arms. It was a rare privilege for a pilot’s spouse. They usually found out they were widows when a staff car pulled up in front of the house.

I comforted mom as she cried, and was a little puffy-eyed myself.

When my dad got home that evening, he looked the same as any other day. “Didn’t you hear about Uncle Sam?” I asked.

“Yes. So?”

I must have looked at him like he was some kind of monster. We all knew pilots who’d been killed, but Uncle Sam was one of dad’s very closest friends.

“Son, Sam Nelson died doing something he loved to do,” he told me, “and the same thing could happen to me any day, so you’d better get used to the idea.”

There Be No Greater Love Than This

I started high school when we got to Tucson. My dad retired in ’78, so I got to go all four years to the same school.

One of my jobs in HS was delivering the afternoon paper. We would get them in bundles and I would read the headlines while I wrapped the others in rubber bands and stuffed them into the bags I wore fore and aft across my shoulders.

On 27 Oct 1978, the headline read that an A-7 had crashed at 7th Street and Highland in Tucson the previous day.

Due to unalterable prevailing winds, approach to the runway at Davis-Monthan AFB led right over the University of Arizona, and still does.

Capt Fredrick L. Ashler had lost his engine on approach (only one engine in an A-7) and stayed in the bird till he was well below minimums for safe ejection, trying to drop it onto an empty practice field across 6th Street from the U. When he thought it would hit where he wanted, he bailed out. He got out at about 200 feet AGL (above ground level). But when he left the controls the bird slipped off to the right, narrowly missing Mansfeld Junior High School.

A 22 year old woman in a car was killed, and her sister severely injured. Others nearby suffered less serious injuries.

Capt Ashler survived, despite having ejected at suicidally low altitude. These days, they have “zero zero” ejection seats. You can pull the handles at zero altitude and zero speed and a rocket in the seat will get you high enough and another device will fully deploy the ‘chute and you can survive, as long as you don’t drop down into your own fireball. They did not have zero zero seats in SLUFs when Capt Ashler bailed out. I think he did the very best he could with the cards he was dealt. But he had to live out the rest of his days–likely still does–knowing that young lady (and I think, later, her sister) died.

On the one hand, I was fatalistic about it. You can look both ways before entering an intersection, and wear your seatbelt religiously, but if an airplane drops on you, it’s probably your day to go. God is calling you home.

But somebody had at least partial control of the outcome, and it wasn’t the young ladies in that car. I had grown up around crashes and knew they happened sometimes, but that was when I realized the awesome responsibility pilots have, not only for the lives of every soul on their plane, but for anyone it might drop onto. I vowed to myself, and before the Lord, that if my bird was ever out of power over a populated area, I would ride it in, rather than taking that chance.

Easy to say or even to swear. Probably not so easy to do. Fortunately, I never had to find out if I truly had the spirit of sacrifice, of service before self, to be a man of my word in that department.

Many bomber pilots in WWII had to find out. When their aircraft were too damaged to get home, hundreds–perhaps thousands–of pilots stayed at the controls of their stricken bombers, fighting to keep them from stalling or spinning long enough for their crews to get out. When the last crew mate was away, many pilots went to bail out themselves, only to be pinned against the inside of the fuselage as she tumbled out of the sky.

CAP

When I was a freshman in HS, I joined Civil Air Patrol, which I liked better than Boy Scouts. For one thing, there were girls in CAP. Pioneering and smart Wendy K. Girton, one of our CAP cadet squadron leaders, was later admitted to the third Air Force Academy class to accept ladies (’82), and became their first female falconer.

In the summers, our CAP squadron had an activity called “Operation 4th Lieutenant.” Before getting commissioned as 2nd lieutenants, Academy (and ROTC) cadets visited a real operational air base over the summer as a taste of what they might see and do. It’s called “Operation 3rd Lieutenant.” Our CAP version of that experience was mostly sponsored by the enlisted folks–some of whom had kids in our squadron. It allowed us to hang out at and tour various functions on base.

I remember helping to change engines on the flightline. DM still had older A-7Ds, which were being replaced by the A-10s. It was hot on the flightline in the Arizona summer, and the insides of those aircraft were even hotter. The A-7 sat close to the ground, as did its burning kerosene exhaust. Us smaller kids got to crawl up inside and connect or disconnect hydraulic line and fuel line hoses. If we were reaching up to connect or disconnect a line, the hydraulic fluid ran down our arms. Sometimes it ran into our eyes and stung (gloves and eye pro were for wussies in those days). We scraped our knuckles turning wrenches. I gained a special appreciation for all those who labor to keep our aircraft flying.

My dad had told me that when I flew for a living, the very first thing I should do when I got out of the bird after a mission was to thank the ground crew that I came back. After working on the flightline, I had some idea why.

We also got to hang out in the control tower. I remember how boring it was–till a B-52 blew some tires on landing. Then it suddenly became a flurry of activity. I’d been watching it land through binoculars when I saw a puff of smoke by the front gear, and she lurched to one side. Somebody ganked the binos out of my hands. There were lots of frenetic phone calls and radio activity. The Fire Crash Rescue trucks raced over there. DM’s air traffic coming in to land got diverted to Tucson International Airport. Then, five or ten minutes later, the controllers were back to boredom, smoking and looking at the view as if nothing had happened.

I found out it was not unusual for older birds to lose tires on landing, or to declare IFEs (in flight emergencies) on the way in. Older aircraft came to DM on their last flights before being relegated to MASDC, the Military Aircraft Storage and Disposition Center–i.e., the boneyard. Before that final flight, crew chiefs from all over their last base would come by replacing any new components on the retiring bird with older worn out components (including tires) from their own. They took volunteers for that last ride.

Gear Down and Locked, Check

There was also a small control tower–little more than a glass-walled shack–in a trailer at each end of the runway. Pilots had to sit in it all day, every day, one of those “other duties as assigned” that went with the job description, but which was enjoyed little more than being the guy who made sure the squadron snack bar was well stocked.

Their sole mission was to check approaching aircraft to make sure their landing gear was down and locked. Lowering the gear was rarely forgotten–aircrews had checklists to make sure they didn’t forget important things like that–but sometimes it malfunctioned, and that was something the pilot should know before she or he tried to set it down.

As a CAP cadet, though, I loved hanging out in that shack.

Visions of Fire

Once, after spending an afternoon at that end-of-the-runway shack, I opted to hike back instead of waiting for a ride. I walked past the burn pit where the DMAFB Fire Crash Rescue crews had BBQed an F-100. Other bases welded together culverts as fuselages with sheet steel for wings as a suitable substitute for an aircraft to set on fire. But DM had a virtually endless supply of real mothballed aircraft in the bone yard, many destined to be sold for scrap, from which to draw.

Not caring about smudging my fatigues with carbon, I climbed into the cockpit to check it out. Plastic was melted, glass cracked, rubber hoses charred. It had a very peculiar combination of smells.

I thought about my dad’s friend Bill Reed, who had been horribly burned in an F-84 crash.

My mom had told us of sharing a room at the Fairchild AFB hospital with burn victims from a B-36 crash.

I tried to think of what I’d have to do if I’d crashed and the bird was on fire. First, jettison the canopy. Next, unbuckle and disconnect the G-suit and O2 hoses. My overactive teenaged imagination took over and I had visions of the visor melting, the oxygen in my mask catching fire. It gave me the heebie jeebies.

Suddenly, I had to get out of there.

Fighter Interceptors on Alert

In the 1970s Davis Monthan AFB had a detachment of delta-winged NORAD F-106 fighter interceptors, to shoot down any Nicaraguan bombers that might try to bomb Phoenix. In ’78 NORAD was run by 4-star General Chappie James, who had flown with my father in the 8th TFW Wolf Pack.

One day I stepped out of the end-of-the-runway shack to snap some photos of a Delta Dart taking off, and got a rude surprise. I had been spoiled by the A-7s and A-10s which constituted the vast majority of DMAFB’s traffic. Neither one had augmented thrust–an afterburner.

The A-10’s General Electric TF34 engines where what they called “high bypass ratio” turbofans. Like on modern airliners, most of the thrust came from the front fan which blew around the engine. That kept it cool. Cooler burning engines were considered desirable on the A-10 because down in the weeds where the Hog was expected to operate, the Soviets had a lot of SA-7 MANPADS (shoulder launched SAMs) that they freely shared with communist revolutionaries throughout the world. The SA-7 tracked on heat.

One of my dad’s few complaints about the A-10 was that it was under-powered. Its high bypass ratio turbofans were also very quiet.

But the F-106, on the other hand, was powered by the Pratt & Whitney J-75 engine, which could augment its thrust with an afterburner or water injection. I had stepped out of the shack without ear muffs or plugs, and when the water injection kicked in, only fifty meters or so away, it was ear-splittingly loud. I dropped my camera.

My CAP squadron also got to tour the alert facility where the F-106 pilots hung out. Mostly they played pool while waiting for an order to “scramble,” a fighter pilot tradition since the Battle of Britain. Once a day or so they would practice running to their jets and going through the pre-flight procedures.

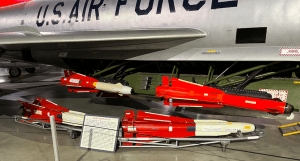

The Delta Dart had triangular wings, and an internal missile bay. When they fired a missile, doors would open up under the interceptor like the bomb-bay doors of a bomber. Racks holding the missiles would pop out into the airstream under the plane long enough to launch the missile(s), and then pop back in as the doors slammed shut. Internal weapons made it more streamlined.

They opened one up to show us the live Falcon air-to-air missiles they had in there. That was one of the few times I was told not to take pictures. Don’t know if they had nuclear tipped AIM-26As or some other version of the Falcon, but the Falcon was nuclear “capable.” Official USAF policy was to neither confirm nor deny the existence or location of nukes. DM was a nuclear target because it was the support base for Titan ICBMs buried in launch silos around Tucson.

Most NORAD interceptors were stationed along the northern tier of the country. If Soviet bombers were heading over the polar ice cap with nuclear bombs for American cities, an AIM-4 or AIM-26B Falcon with its conventional warhead might take one down, or might just damage an engine. On the other hand, you could take out an entire squadron of Soviet nuclear bombers by making them fly through the 250 ton explosion of a nuclear AIM-26A (or the 1.5 kiloton blast of an unguided Genie rocket).

I’m guessing, though, that the live missiles I saw slung in the missile bay of the F-106 on alert were AIM-4Fs or AIM-4G “Super Falcons.”

President Eisenhower had authorized the use of fighters launching air-to-air nukes to defend us from Soviet bombers in 1956 (Command and Control, pp. 164 – 66). According to the 9/11 Commission Report (pp. 16 – 17), NORAD had fighter interceptors on alert at 26 locations during the height of the Cold War, but after the Wall came down and the USSR became the NQSEATUBE (Not Quite So Evil As They Used to Be Empire), that number reduced to seven locations, nation-wide, with two fighters on alert at each.

285,470,000+ Americans, give or take one or two, protected by fourteen fighter planes. The Air Force had many more fighters, of course, but only a handful were ready to defend the continental US on a moment’s–or even 20 minutes–notice.

Post-cold war NORAD planned mostly to counter cruise missile attacks by non-state actors. Few people planned on terrorists weaponizing airliners, although the idea had been in American pop culture for 7 years before 9/11. A suicidal pilot crashing a 747 into the US Capitol building was the climax of a Tom Clancy novel, Debt of Honor, published in 1994.