The ABCDEs of Cover

I first heard about the “ABCs of Cover” from a former Marine, Brad, who was a lead firearms instructor for our office, and a very knowledgeable guy. I added D and E, which are particularly applicable in a civilian, personal protection context.

What’s Cover–and What’s Not

We all know the difference between cover and concealment, and we know that most of the things that work for cover on a movie set in Hollywood don’t really work anywhere else.

Not far from those motion picture studios, LAPD Officer John Caprarelli thought he was behind good cover, a cinderblock wall, during the North Hollywood Bank of America robbery of 28 Feb 1997–till he started getting hit by chunks of the wall, as multiple rifle rounds penetrated through to the other side (Uniform Decisions, pp. 143 – 45).

I took this photo 27 years and four days later, on 04 Mar 2024, at the Bank of America, 6600 Laurel Canyon Boulevard in North Hollywood. Apparently, there had been no privacy screen above the portion of this wall Officer Caprarelli was peering over, from someone’s back yard, when bank robber LP (I avoid propagating the names of criminals) saw and shot at him in 1997. I wouldn’t be surprised if the homeowners installed the privacy screens afterward, to keep cops from using their back walls as cover during gun battles with .30 caliber-toting criminals. I support and appreciate law enforcement, but not everybody, especially in So Cal, does.

LP used a Norinco Type 56 Kalashnikov, almost certainly in 7.62x39mm, and later in the gun battle switched to an H&K model 91, in 7.62x51mm (.308). Not sure if LP had made the switch yet, but whatever he was shooting at Caprarelli and the other officers from the north parking lot (I’m guessing it was .308 from the ’91), it went through the wall AND both sides of a wood and stucco garage behind it.

Obviously, as Clint Smith points out, what constitutes cover is partially determined by what’s trying to punch through it. Many things are “cover” if the enemy is shooting .25 ACP at you. A dumpster or construction equipment might be cover from most small arms. Not many things in our day-to-day environment will protect us from 12.7mm or .50 Browning.

Some things we consider cover, like automobiles, are mostly, at best, shielding–something that might slow or turn a bullet, rather than stopping it.

Cover and Tactical Medicine

During a recent Austere Medicine class, one of the subjects we addressed was Patient Rescue (i.e., rescue in a tactical / kinetic situation, as opposed to a wilderness survival or disaster type situation).

Moving casualties to cover–or moving cover to downed casualties–is one of the three CoTCCC* approved patient treatment options during hot zone / direct threat situations (the other two are tourniquets and rolling a patient onto their side to protect their airway).

“But you can’t go off half-cocked,” as Dick Jonas, who flew in the 433rd TFS when my dad flew with the ‘Nickel, said about killing MiGs over North Vietnam. “It has worked out the other way around.”

You won’t do the patient any favors if you fall on top of them and bleed to death into their airway.

You need a plan.

If a friendly who is downed in the open needs medical attention ASAP–rather than a call to the coroner–and your tactical situation has given you at least a brief moment of opportunity to get them behind something solid, it helps to know that there is more to cover than just cover.

You have other options, or “suitable substitutes,” in a pinch.

The ABCDEs of cover are:

- Accurate return fire

- Body armor

- Cover (actual)

- Distance

- Explosive movement off the X

A: Accurate return fire—you can shelter behind a wall of lead, at least till you run out of ammo and friends with ammo. The only times you can have too much ammo are if you are swimming, or on fire.

“Their carbines were their protection. Concentrated firepower is far more effective than passive barriers in forcing an enemy to keep his distance.”

–Charles K. Mills, Harvest of Barren Regrets, p. 266

Bear in mind, though, that in the ‘States, return fire must be ACCURATE. There is no such thing as “acceptable” collateral damage outside of a war zone, because you are responsible for the final resting place of any bullet you launch. Avoid even saying the words “suppressive fire” in a Stateside context.

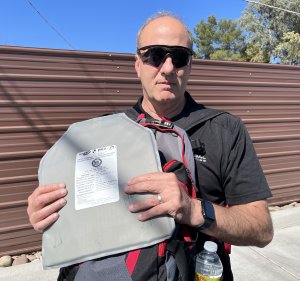

B: Body armor and ballistic shields / helmets–You probably don’t carry a ballistic shield at the mall, but each of my kids had a light panel of Level IIIA armor in their school backpacks. Vests and even helmets are available on the civilian market.

You probably won’t be wearing body armor when you are jumped in a parking lot after work, but if there is a brewing fight, and you have your armor nearby, you can don it before hostilities come to a head.

As long as it doesn’t hinder your access to it in places where you might be attacked, it’s a good idea to SECURE YOUR ARMOR AS YOU WOULD SECURE A FIREARM when you are not wearing it.

But you should be wearing it? (See One More Thing below.)

C: Cover, aka “hard cover”–is something solid that will stop a bullet. The wheels and engine block (which does NOT take up the entire engine compartment) are a good start. If the car is pointing at the bad guy, “tucking in behind a tail light,” as Clint Smith suggested, puts the “cage” of modern (mostly plastic bodied) cars, the narrow A, B, and C pillars, between you and the threat.

The A, B, and C pillars are more bullet resistant than most people realize, but they are also so narrow as to be almost useless. Here, a student tries to put holes in the target behind the van by punching THROUGH the pillars (and the rear passenger door frame). She was unable to reach the target through those barriers with Speer 124 grain 9x19mm +P Gold Dot jacketed hollow points, but a bad guy would probably aim at the part of you he can see–in this case, the head and shoulders of the cardboard target. Don’t be like that target. When Clint Smith said “tuck in behind a tail light,” the key word was “tuck.”

Several cars between you and the bad guy(s) are better than one.

Try not to “crowd” your cover. Been there, done that. I know that even a few inches of reverse slope can be comforting when bullets are buzzing past you. But no matter how warm and fuzzy it makes you feel, try to stay back from it, and away from walls too, when problems are being solved kinetically.

D: Distance–Most bad guys can’t shoot worth a darn. Even if he knows what he’s doing, the farther away you are, the harder you are to hit.

Do NOT run directly away, if you can avoid it, as doing so leaves you on the railroad tracks of his attack.

If you must, because your exit path is channelized (for example, in a hallway), try to zig-zag IRREGULARLY (pilots call that jinking), not following any particular pattern. This goes hand in hand with E, below.

E: EXPLOSIVE movement off the X–YOU MUST MOVE NOW, especially if you are close, as you most likely will be when you are ambushed. You don’t have to run directly away; you just need to get off the X, since all bullets are sent to your last known address. This movement must be “explosive;” not a saunter, walk, or a jog. Drop down into the sprinter’s blocks (we call that a Pekiti takeoff) and MOVE.

When we first learn movement, of course we start slow till we get the motions down. Crawl –> Walk –> Run. We gradually speed up as your proficiency increases. Eventually, you need to practice at full speed.

So there you have it: cover, plus four suitable substitutes for cover. The ABCDEs. Just thinking about it makes me want to throw some of my old Jackson 5 vinyl on the turntable.

One More Thing,

For Those of You in Uniform

If you work in a job where you wear a big target on your uniform, like law enforcement, security, or even EMS these days, you should be wearing armor. You will not likely get an engraved invitation before the next time somebody tries to kill you. Trying to put it on after the gunfight begins didn’t work out so well during the FBI’s Miami gun battle.

On 11 Sep 2004, USAF Security Forces Airman First Class Brian Kolfage stepped out of his tent at Balad and a 107mm rocket landed 5 feet away, removing his legs and right forearm. There had been no “incoming” warning. Like I said, no RSVPs.

As I prepped to leave my civilian job for my last active duty deployment, I got some advice from Walter D, who had taught my agency Field Armorer courses. “Wear your body armor every day,” he said. “Every single day.”

Wally had been a SEAL in Vietnam. His son was in the Sand Box.

That deployment to Kuwait started in the Spring and ended in the Fall, with a hot Middle Eastern Summer in the middle. I wore by body armor from the moment I left my hardened billets till I got back to the bunks at the end of my shift. It darned-near killed me, especially at first. Between the armor and the ammo I weighed 60 lbs more with it on, and the temps were well into the triple digits. But eventually, it didn’t bother me.

I was an area security supervisor. Most of our posts and patrols were inside the wire. Our regs only required us to have our vest and helmet with us, not on us. When I got there, the biggest danger facing us was our own complacency, a pervasive assumption that nothing bad ever happened outside of Iraq and Afghanistan. Expeditionary readiness (ExpeRT, formerly Silver Flag) pre-deployment training for Gulf States was shorter, and taken less seriously by students and cadre alike.

Instructor tip: When you are teaching survival skills, some of your students (especially those were voluntold to be there, by their duty supervisor or their spouse), may not be overtly enthusiastic. But if you don’t give a rat’s, NOBODY in your course will.

The vast majority of Kuwaitis–at least the ones I met, who invited us into their homes for chai or meals–loved us. All had lost relatives to the Iraqis back in ’90 and ’91. As far as they were concerned, killing Iraqis was the Lord’s work, and in those days the US was in that business.

While compared to a few miles north in Iraq, or to Afghanistan, being “in the rear with the gear” was relatively tame, but US military personnel had been killed by Tangoes in Kuwait, and one of the 9/11 hijackers had been a Kuwaiti.

Khobar Towers was a lot farther from “the front” than we were. How’d that work out for them?

The kids I supervised, most of whom had not been born 28 years before, when I enlisted, figured that if wearing my vest all day, every day didn’t kill me, it might not kill them either. After a while, perhaps not wanting to be outdone by the old man, or (I like to think) seeing the logic of my “no engraved invitation” postulate, most of our SF troops were wearing their armor all the time, too.

Mindset

Perhaps more importantly than the ballistic protection it provided, wearing it front-loaded the idea into their brains that today might be the day it’s needed. Not wearing it had programmed the opposite of vigilance and diligence.

Deterrence

If nothing else, seeing us wearing it through the wire might even have made potential enemies think, “Let’s hit al Mubarak, instead of Ali al Salim. The security here is switched on.”

Domestic Tranquility

Stateside, wearing your armor is as much so your spouse can feel you wearing it when they hug you on your way out the door, as it is for the ballistic protection it provides.

You don’t get shot at all the time, but your marriage needs reinforcement every single day.

When you deploy downrange, seeing photos of you in your armor helps them sleep better at night.

Most spouses can handle the uncontrollable risks, provided they know you are controlling the risks you can.

–George H, lead instructor, Heloderm LLC

About half of this posting is from the training summary, or after action report, for the Austere Medicine class of 19 Mar 2022.

*CoTCCC is the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care, which directs and updates the TCCC curriculum.