“Stand Your Ground” and “Castle Doctrine” in Arizona

A student wrote to me after a class, asking about some phrases she had heard elsewhere: “stand your ground” and “castle doctrine.” Here are some of the things I explained to her.

STAND YOUR GROUND

The phrase “stand your ground” is often bandied about by the media, and very misunderstood. It should instead be said that Arizona has no legal duty to retreat. Some jurisdictions, particularly on the East Coast, do. There, if you are cornered in your own basement by a man with a knife, you are required to try to climb out the basement window, even if you KNOW that will only get you stabbed in the back. Arizona, fortunately, is not one of those sorry places.

The words “stand your ground” do not even appear in the relevant statutes. Arizona Revised Statute (ARS) 13-405.B states: “A person has no duty to retreat before threatening” [for example, brandishing a weapon and telling the bad guy to leave] “or using deadly physical force pursuant to this section if the person is in a place where the person may legally be and is not engaged in an unlawful act.”

What does that mean? It means that if you can’t exit without being stabbed or shot in the back (say, trying to climb a fence), you are not required to turn your back on the bad guy, because doing so would put you at a significant tactical disadvantage.

What does it NOT mean? For one thing, you can’t use “stand your ground” as a moving force-field to push people around.

ARS 13-404.B.3 states that you cannot use force if you verbally provoked the encounter, unless “(a) The person” [who verbally provoked the incident] “withdraws from the encounter or clearly communicates to the other his intent to do so reasonably believing he cannot safely withdraw from the encounter; and (b) The other nevertheless continues or attempts to use unlawful physical force against the person.”

In other words, you cannot legally pick a fight with someone and then shoot him because you heard Arizona has a “stand your ground” law, although the media sometimes portrays “stand your ground” that way.

For example, you are at a public event and somebody steps on your toe. You yell “Hey, watch where you are going!” The clumsy oaf turns on you, raises his fist, and says “What did you say?” At this point, if you are armed, you MUST attempt to DE-ESCALATE, verbally (“My bad…I thought you were someone else…No offense meant…”) or simply LEAVE if you can. Otherwise, if things spin out of control, you might end up shooting somebody over what started as an avoidable matter of pride.

Also, a bad guy cannot break into your house (an unlawful act) and then, when you tell him you will shoot him if he doesn’t leave, claim he has a right to “stand his ground.” It’s not “his” ground if he has no legal right to be there.

ARS 13-411.A lists a series of heinous crimes that justify anyone, not just law enforcement, using or threatening deadly / physical force to prevent. These are no-brainers such as murder, arson of an occupied structure, child molestation, rape, etc. Section B of 13-411 again reiterates the so-called “stand your ground” language: “There is no duty to retreat before threatening or using physical force or deadly physical force justified by subsection A of this section.”

Here’s why. Let’s say you see someone dragging a kid toward a car. The kid is screaming “You’re not my daddy! Leave me alone!” You and some construction workers tell the man to stop. He claims to be the father, telling you the kid ran away. You dial 911, request police assistance, and then tell the alleged “dad” you would like him to stay there until the cops can verify his story. He does not. Instead, he starts hitting the kid in the face and then kicking the kid, shoving the kid into the trunk. You and the construction workers physically restrain the “dad” / kidnapper. Obviously, if Arizona had a duty to retreat, you could not have intervened on the kid’s behalf in the first place.

Same applies if you hear someone screaming “Rape!” or you see some loon attacking a crowd with a knife and run over there to get a clear shot on the bad guy.

Bill Badger, a 74 year old Arizona resident, had zero legal duty to retreat when a maniac shot him, US Rep Gabrielle Giffords, Christina Taylor Green, and numerous others on January 8, 2011. Good thing our laws are written that way, or Pima County deputies would’ve had to arrest Badger for tackling and beating the snot out of the murderer, saving countless lives.

Joseph Zamudio, who was lawfully carrying a concealed pistol for defense, ran toward the sound of that shooting (not being required by Arizona law to retreat), bringing his pistol with him. Had the shooting still been going on when Zamudio got close enough, Zamudio might have lawfully shot the murderer to stop the killing. Instead, finding Badger, Steve Rayle, Roger Sulzgeber, and Patricia Maisch wrestling with the bad guy, Zamudio chose to go hands-on too.

I strongly suggest you read ALL of ARS 13 chapter 4. I am not a lawyer, and neither are you, but most of it is pretty straightforward and not difficult to understand (as legislation goes). 13-412 (“Duress”) seems somewhat far-fetched; I think the legislators had been watching too many movies. 13-417 (“Necessity defense”) is more complicated than it needs to be, but there, again (in 13-417.B) it states “An accused person may not assert the defense under subsection A” [for example, “I had no other choice! He would have killed me!”] “if the person intentionally, knowingly or recklessly placed himself in the situation in which it was probable that the person would have to engage in the proscribed conduct.” If you walk into Tucson’s landmark biker bar The Bashful Bandit, an hour before closing, and yell “Motorcycles suck!” don’t be surprised if you get a knuckle sandwich. “Stand your ground” will not protect you.

CASTLE DOCTRINE

The so-called “castle doctrine” is another concept that is treated disingenuously by the media. The phrase itself dates back to 1604 in English common law, when (in Semayne’s case) the Attorney General of England (Sir Edward Coke, if you’re a Trivial Pursuit fan) determined

“…the house of every one is to him as his castle and fortress, as well for his defence [sic] against injury and violence as for his repose.”

Yet, Coke went on to explain, agents of the crown could lawfully break and enter if they had reason to believe that a felon was inside, or there was a crime being committed inside, and they announced their presence and intent. That “knock and announce” rule is in western law enforcement to this day.

Many in the media would have you believe that according to this so-called “legal doctrine,” a person’s mere presence in your home technically gives you a free pass to shoot them. Reporters rail against this (erroneous) concept, and for good reason. Obviously, if it were true (it is NOT), that would be a slippery slope. You could invite someone over for Thanksgiving, then blow them away for saying that the stuffing is dry, with zero legal consequences. It is NOT so.

Here’s what Arizona law REALLY says, at ARS 13-407:

“A. A person or his agent [say, your brother-in-law who’s spending the night, or the clerk in your brick and mortar store] in lawful possession or control of premises is justified in threatening” [that word is important here] “to use deadly physical force or in threatening or using physical force against another when and to the extent that a reasonable person would believe it immediately necessary to prevent or terminate the commission or attempted commission of a criminal trespass by the other person in or upon the premises.

A person may use deadly physical force under subsection A” [what you just read above] “only in the defense of himself or third persons as described in sections 13-405 and 13-406.”

Here are some examples of what that might mean:

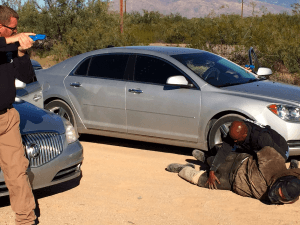

Example 1: A shirtless man broke your window and is climbing into your kitchen. He’s covered in blood from the broken glass. He’s not getting too far, because he’s really drunk. You CAN hold him at gunpoint till the cops get there (that actually happened to somebody I met; it turned out the guy in the window lived two doors down and couldn’t figure out why his key didn’t work). You CANNOT shoot him unless you have reason to believe he plans to hurt you.

Example 2: There is a man in your living room at 0200. You did NOT invite him in. You CAN point the gun at him and tell him to lie down on the floor. When you do, he turns around and leaves. You CANNOT shoot him.

If, on the other hand, he draws a gun while running for cover behind the couch, then you would be justified in shooting him, even if your bullet enters his side or back.

Example 3: There’s a man in your living room at 0300. You DID NOT invite him in. When you order him to leave, he comes at you with a crowbar. You CAN and probably SHOULD shoot him.

Example 4: Your boyfriend is spending the night (you DID invite him in). At 0400 you wake and find him molesting a 12 year old who is living in your house. When you confront him, he pulls out a knife and holds it to her throat. You MAY shoot him, legally; whether you can or should (or not) depends on your skills with a gun, if they are moving, and other moral and physical factors–see Appendix.*

Example 5: You look through your window at 0500 and see somebody breaking into your car. You COULD go out there and hold him at gunpoint, but you CANNOT shoot him just for stealing your car stereo (or even your car). More importantly, you give up a significant tactical / safety advantage (the strong walls and locked doors of your “castle”) if you foolishly choose to go outside to confront him.

Example 6: You hear honking in your yard. Your daughter has locked herself in a car to escape from a date-rape. The guy is breaking into the car. You CAN shoot him to “repel boarders,” as long as you can get a firing angle that does not endanger her or your neighbors. If she can drive away instead, it would be safer if you don’t leave your castle to go out there, placing yourself at a tactical / safety disadvantage.

Clear as mud? Again, I’m not a lawyer, but I spent almost my entire adult life enforcing somebody or other’s rules, so I have some clue about them. When I teach pistol defense classes, we go over Use of Force in better detail, and we do some role playing, which is an important way to help you prepare for such crucial decisions. You are right; there are countless variables.

NOTE: When I quoted the statutes above, I added items in brackets [like this] for clarification; they are NOT part of the quoted statute. Likewise, I highlighted some portions for emphasis. The above information is posted on this site for educational purposes, and does not constitute legal advice from an attorney.

If you own or use a firearm or knife or baseball bat for defense, you have a responsibility to learn the relevant laws and regulations in your jurisdiction, and to think very seriously about use of force issues BEFORE you find yourself in a confrontation. Heloderm can help you with your journey.

–George H, Lead Instructor, Heloderm LLC

Appendix

*Hostage Situations

One final bit of free advice about hostage situations: never, EVER, give up your gun. A hostage taker will say “put down your gun and kick it over here, or I’ll shoot him.”

Think about that.

Historically, when a cop has given up his gun to save the life of a hostage, they BOTH get shot.

When they do not, the cop, at least, gets shot.

It has happened that the bad guy had a fake gun, or no ammo, and the cop giving up his gun only gave the murderously irresponsible bad guy the weapon the bad guy later used to end lives.

Don’t be that guy. Never, ever, give up your gun.

You don’t have to use it. You can (and probably should) delay and talk till the professionals get there. But never, ever, give up your gun.

Are we clear? Seriously–never, EVER.

See Hostage Rescue in the Home and Where to Shoot a Kidnapper for more about hostage situations you might encounter.