Impact vs Edged: Advantages and Disadvantages of Crenelated Flashlights

I have known many true warrior protectors in my time.

One of the finest I’ve met in the last couple years is a UAV (drone) operator. While we tend to think of those guys as glorified couch potato video gamers, this guy (let’s call him Ay-Ay-Ron) walks the warrior walk. He maintains excellent small arms and empty hands skills.

Another of the better warriors I met at about the same time is T. T was an Army grunt in the GWOT–the Global War on Terror. He was also a deputy on Hawai’i’s equivalent of state police.

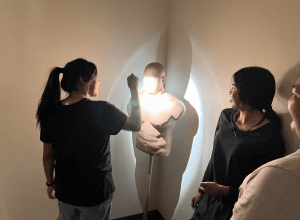

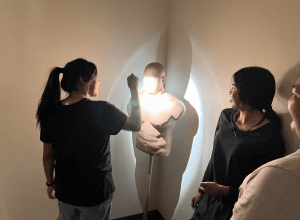

Not too long ago we were teaching a Ladies’ Personal Protection class. Ann, a Heloderm Personal Protection coach, was telling the students the advantages of carrying a small, powerful flashlight on one’s person. Ann is petit, and was showing the student how easily one could be carried, even on a smaller-framed person.

Ay-Ay-Ron pointed out that a small flashlight could be a force multiplier when held in the palm during Hammer Fist strikes we had learned earlier in the day.

Instead of hitting them with the pinkie side of your palm and fist, you could hit them with the bezel (light) end of your flashlight as well (I met a SWAT guy who completely cold-cocked a hostage taker with the bezel end of a small weaponlight).

T pointed out that some flashlights now come with crenelated bezels: the business end has raised portions, like the rampart of a castle wall. These crenelations can rip and tear the flesh of the guy you need to strike with the flashlight.

Question: are those crenelations a good thing, or a bad thing?

The answer is “Yes.”

Background

When I was just starting out in civilian law enforcement, there weren’t nearly as many options in the flashlight department. Most of us, myself included, carried a small AA powered Mini-Maglite for writing tickets on night shifts.

We used bigger flashlights on prowler calls, of course. Larger Kel-lights and Maglites were popular. They were as bright as you could get at the time, and would light up an alley or the side of a warehouse.

The longer C-cell, D-cell, and rechargeables also doubled as truncheons, saving officers the hassle of lugging around both–at least until the Malice Green case (see below). Even if you carried both a baton and a large, heavy flashlight, the flashlight might be what you had in hand if you needed to parry a stab with a knife or a swipe with a pool cue, and immediately riposte (hit back), so flashlights often doubled as a baton or night stick.

Billy clubs and adequately powerful flashlights were so long (before expandable batons and smaller “tac” lights came along) you had to take them out of their belt rings when you were sitting in your car. If you had to bail out of your vehicle fast to chase a burglar at night, you might not have time to slip your (ironically named) night stick in its ring, especially if you had a big flashlight in the other hand.

Billy clubs and adequately powerful flashlights were so long (before expandable batons and smaller “tac” lights came along) you had to take them out of their belt rings when you were sitting in your car. If you had to bail out of your vehicle fast to chase a burglar at night, you might not have time to slip your (ironically named) night stick in its ring, especially if you had a big flashlight in the other hand.

I was issued a rechargeable Kel-light as a law enforcement park ranger, till it got too wet and shorted out while we were searching Glendo lake for a drowning victim at night. Lights with disposable batteries were water resistant, but if you were on a swing or mid shift, replacing batteries got prohibitively expensive.

CPD issued me a rechargeable Maglite about the size of a 4 or 5 D-cell. CPD gave the new guys worn-out equipment no longer wanted by the older officers, and that Maglite was no exception.

The Maglite I got from CPD would last for the first few calls of a night shift before dying. Rechargeable batteries have a limited service life even to this day; after a few years, your cell phone or laptop no longer holds a charge, and that technology has much improved since I was a rookie. I was saving up my meager income for a replacement battery (the department wasn’t about to fess for one) when something happened that changed my approach.

Shots Fired

My first Shots Fired Man Down call on CPD came on the afternoon of a swing shift. We raced over there, bailed out, and ran to the house. I kept the big Maglite by the seat, but it was broad daylight so I left it in my cruiser (that POS, an ’89 Caprice, also had problems; sometimes the electronic ignition would die when you’d key the radio mic–but I digress).

We stepped over the victim’s prostrate body, and searched the house for the suspect. I wound up searching the dark basement with that AA Mini-maglite I carried on my belt. These days, I’d have told the officers I was with to hold at the top of the stairs while I got the equipment I needed out of the cruiser. But I was young and dumb and for some reason the more experienced officers were in a big hurry to find the guy.

The suspect turned out to be a gal, and the guy on the floor of the living room wasn’t even that badly hurt, but the very next day, I dug into the Gall’s catalog (there was no e-commerce back then) and used up my discretionary income for the next paycheck or two ordering a SureFire 6P.

The 6P

SureFire (originally called Laser Products) was one of the first companies providing smaller, durable (and expensive) “tactical” lights. These days, you have many, many more options.

Weapon mounted lights were just becoming a thing, although the idea had been around for a while; I read in A Rifleman Went to War, Herbert McBride’s WW I memoir, that he had found a German Mauser with an electric torch attached during a raid of Hun trenches.

SureFire specialized in weapon mounted lights. They introduced a powerful hand-held light they called the model 6P, using many of the same components. Most of their offerings got their juice from relatively small but powerful (and fairly expensive) CR-123 camera batteries.

The 6P had a button type thumb switch on the opposite end from the bezel. It could be locked on by screwing the switch end on tighter, but normally it was backed off about a quarter of a turn past where the light went off. That way, it only came on when you pushed the button, and importantly, turned off automatically (like a Star Wars lightsaber) if you dropped it.

The thumb switch made the 6P ideal for the Harries flashlight technique taught at Gunsite.

The compact size of the 6P meant it wouldn’t get in your way if you left it on your duty belt (or for what later came to be called EDC, every day carry, when concealed under plain clothes). I no longer had to be in the habit of grabbing my flashlight and slipping it into a belt ring as I clambered out of my cruiser, as we did with batons and bigger flashlights.

That 6P became a constant companion through my Border Patrol days, 2 military active duty call-ups, and plain-clothes special agent duty since.

Greg G, a former Marine, career Border Patrol agent, and senior firearms instructor who now volunteers for Heloderm, got his first 6P in 1989. Like me, he was too poor at the time to afford many CR-123 batteries, but the 6P was a dependable backup to his rechargeable Streamlight SL-35 if the latter died or got left in the car.

The Battery Principle: 2 is 1

One corollary to Murphy’s Law states that:

The battery of any device will run out of power the one time in your life you really need it.

Accordingly, we have the Rule of Twos:

Two is one, one is none.

You should carry a small “tactical” flashlight, even if it’s daylight (we spend most of our lives indoors, and sometimes the power goes out). Consider the light in your cell phone a backup to your EDC (every day carry) flashlight.

A Battery Park

To illustrate the usefulness of a small powerful flashlight in broadcasting the message that you are paying attention to your surroundings, I often regale students with an experience I had in a battery park on the north end of San Francisco.

Harbors and bays used to have coastal artillery batteries designed to keep the ships and landing craft of invading navies away. Now many are parks. The north and south ends of The Golden Gate, the ocean entrance to San Fancisco Bay, are lined withsuch parks.

My wife and I and a few friends were headed back to our cars after a long day and evening of playing tourist.

We were walking roughly north-northwest across a battery park, toward a parking lot. I noticed a group of three people, later identified as “military aged males,” at our 7 o’clock. They were headed north northeast, and walking slightly faster. Each time I glanced back they were a little closer. They were on an intercept course.

The lights of San Fran were behind us, and the lights of Sausalito reflected off the waters of the Bay, but it was dark out in the middle of the park. When those guys were about 10 or 15 feet behind us, I flashed the light of my 6P across their eyes.

I didn’t keep them in the spotlight. It was just a quick flash. Not enough to piss anybody off, but enough to let them know I knew they were there.

If I’d been really switched on, I would’ve used that brief moment of illumination to look at their hands, or for any of the other things (mission focus, target focus, number of whites to the eyes, appropriateness of the clothing to the environment, etc) that we observe to stay “left of bang.” Sad to say I didn’t even get a good description of them. Turned out, it didn’t matter.

Ever been to an aquarium or scuba diving or just watching an underwater special on National Geographic, and seen those schools of fish who all, suddenly, change direction at the same time? That’s exactly what happened with those three guys.

One minute, they were headed north-northeast. After I zapped them with the light, they suddenly turned due west and kept going, without saying a single word to one another.

That’s the power of letting potential predators know that you are paying attention. A small but powerful flashlight is cheap and easy messaging in any language that you would not be easy prey.

Understanding Impact Tools

My wife’s side of the family were mostly New York cops, going back generations. During the 1800s and the first half of the 20th century, height and brawn was a major requirement for being a law enforcement officer. The ability to swing a stick, and the command presence to talk down (or wade into) an unruly crowd, were a lot more important than polite speech or investigative prowess.

That began to change in the 1960s and ’70s, when the civil rights movement and anti-war protesters began to paint the police as brutal thugs (that description wasn’t always entirely inaccurate). Law enforcement training was expanded (LE training has continually evolved and improved since then). Each state began to have peace officer’s standards and training (POST) board to certify peace officers, not entirely unlike the way doctors & nurses are licensed.

Use of Force models were introduced, in an effort to make the force used by police proportional to the resistance offered by those resisting arrest. Along the way, the truncheon / Billy club / night stick, standard peace office equipment since Sir Robert Peel introduced modern policing concepts in the 1800s, began to have a dual purpose; it could be either a less-lethal defensive tool, like pepper spray, or a deadly force implement, depending on where you hit somebody with it. Actually, it always had been, but we began to care more about where and how you hit somebody with it, and even what you called it.

When I went through impact weapon training, calling it a “stick” or “club” instead of a “baton” would earn us extra laps or pushups. They didn’t want such evil terms ever slipping from our lips in court (the NRA insists that instructors say “rifle” or “pistol” or “firearm,” but never “weapon,” for similar reasons). A “baton” is a tool for applying appropriate force, as a scalpel is used to cut out cancer. A “stick” is something cave men flogged each other with.

Baton Retention

We also got extra laps if we let it slip from our hands, as golf clubs sometimes do, while we were swinging it around. Obviously, if you lose your baton in a melee, it can be used upon you or your partners. Part of our training was in how to keep batons from being torn out of your hands and used against you.

Retention is something Heloderm can teach you, whether the long thing in your hands is a baton or a carbine. Retention is not so much of a problem with small, hand-held flashlights, because there isn’t much outside your palm for the bad guy to grab.

Rodney King

The Los Angeles police department was issuing side handle (tonfa / PR-24 type) batons on 03 Mar 1991, when King, who was driving drunk (he had also been smoking marijuana) led police on a 117 mph chase. King had been convicted of robbery after (ironically) striking a Korean store owner with a tire iron and stealing $200 on 03 Nov 1989 (there’s gotta be a life lesson about reaping what we sow in there somewhere). He’d served one year of a two year sentence, and was out on parole.

Incidentally, I read King’s (revised) version of the robbery in his book, The Riot Within: My Journey from Rebellion to Redemption (co-written with Lawrence J. Spagnola; HarperOne / HarperCollins publishers, 2012, pp. 31 – 37). Although King admitted guilt 10 days after the robbery when the cops tracked him down and found a check from the Korean store in his trunk, King’s 2012 autobiography version of the events of 03 Nov 1989 was that his alcoholism had left him broke. He’d gone fishing to put food on the family table that evening, and caught a few big ones but a large rodent had stolen his fish. Despondent, he walked into the convenience store and asked to buy a stick of gum with food stamps. King wrote that the store owner refused to take his food stamps and hit him with a tire iron. King threw pies off a rack at the store owner and ran away. At least, that’s King’s version of the event in which the store owner was severely beaten by somebody.

On 03 Mar 1991, after exiting the freeway, police say King drove through residential streets at 55 to 80 mph. In his book, King said he was only doing 65 mph on those residential streets, and that his Hyundai couldn’t go faster than 100. 65 mph is OK in your neighborhood, isn’t it? King did blast through at least one red light. When CHP and LAPD finally stopped him, King refused commands and didn’t go prone even after being tased. Four officers attempted to control him with empty hands, but he stood back up, shaking them off. He then (this is seldom brought up) charged at one of the officers (Powell).

The side handle baton is capable of being used for arm bars and as a come-along. King was a big man, and the alcohol and THC in his system made him somewhat resistant to pain compliance techniques (they thought he was on PCP at the time), but while King was on his hands and knees, they could have used their side handle batons for leverage to control his arms and take him the rest of the way down into a prone handcuffing position.

I read somewhere that by 1991 the LAPD had a “keep it simple” training philosophy, and did not teach the many (and admittedly complex) come-alongs, takedowns, or vehicle extraction techniques the side-handle baton is capable of (when I went through the Wyoming Law Enforcement Academy, not long after that, they only taught us straight baton techniques, to keep it simple).

If it’s true that LAPD was not teaching officers to use their issued side-handled batons for take downs and come alongs in 1991, that’s kind of ironic.

I have a book called Tonfa: The Side Handle Police Baton, published in 1982 by Officers Robert L. Jarvis and James D. Markloff (at the time, 23 and 7 year veterans, respectively, of the LAPD), with the assistance of the LAPD’s Physical Training and Self Defense Unit. It thoroughly details many different ways a side-handle baton can be used to control a suspect without beating him–as well as ways to strike a suspect if necessary. Two LAPD Captains wrote the introduction, noting that nobody has enough training time to master all of the side-handle’s capabilities, but that the book should help them practice on their own.

I also have an earlier work, published in 1978, called Fundamentals of Modern Police Impact Weapons. The author, Massad Ayoob, is on the cover holding a side handle baton as if to block a strike. On the jacket, it says

Although few police agencies require more than a minimum competence with impact weapons, the skillful use of such arms is perhaps more important in today’s law enforcement climate than ever before. This book places stickfighting in its proper perspective. The author discusses a variety of impact weapons, techniques and tactics for their use, the psychology of the impact weapons, training methods, and legal and moral factors. [emphasis added]

. . . moral factors . . .

The LAPD officers trying to arrest King beat him savagely with their batons.

We might never have heard of Rodney King, except that this happened not far from George Holliday’s apartment. Holliday was a plumber who had recently bought a video camera (no smart phones in those days). He video taped King’s beat-down and shared the video with a news station. He took video from before the beating, of when King was not complying with commands, but the several-second clip that the news showed people, and became iconic (these days, it would have “gone viral”), was of King on his hands and knees, getting whacked repeatedly.

Incidentally, Holliday died recently (on 19 Sep 2021) of COVID-19. These days we would call him a citizen photo journalist. He claimed to never have made any money off the video, although they auctioned the camera he took it with for a starting bid of $225,000.00.

Four LAPD cops (including one who never hit King, but was nearby) were brought to trial and a mostly white jury (a little brown and a little yellow, one “biracial,” but none black) acquitted them. The constitution, after all, guarantees a speedy and public trial by a jury of the accused’s peers, not the victim’s peers. The jury apparently figured that if you’re driving drunk through town at 100 mph, endangering all and sundry (including your own two passengers), while out on probation for beating and robbing someone with a metal bar, you probably deserve to have your skull caved in.

I do NOT necessarily agree, but I once prosecuted a young adult who was making a little scratch on the side running illegal aliens. He had so few in his car, he wouldn’t have met the minimum guidelines in Arizona for prosecution. They’d have taken his photo and prints and told him not to do it again. But when the police tried to pull him over, he ran from them, entering an intersection against a red light at a high rate of speed, and T-boned a family. It’s a miracle no one was killed. Because his actions resulted in injury, and would therefore have an upward departure from the ridiculously low sentencing guidelines for smuggling humans, the AUSAs (assistant US attorneys) were willing to take the case.

As we were waiting for the public defender’s pre-trial folks to interview him, I told him that if he had simply pulled over and stopped, without endangering his fellow citizens, he would have walked, and we wouldn’t be having that conversation. I explained I was putting him away long enough for his brain to mature into making better decisions.

You have ZERO constitutional right to endanger the lives of your fellow citizens by running from the police. As the soulful singer of the intro to the TV series Beretta sang,

Don’t do the crime, if you can’t do the time.

In April of 1992, after the officers who beat King were acquitted (one had a hung jury) on State excessive force charges, a large scale insurrection took place in Los Angeles. Over 50 people were killed, and over 2000 were injured. Approximately 3600 fires were started, 1100 buildings destroyed. Another 2600 or so buildings were damaged. About 45% of the looting, vandalism, and arson was directed at the Korean American community, with about 2300 Korean owned businesses looted or destroyed (see Appendix II for how the Border Patrol helped to safeguard lives and limit the destruction).

Judicially, the federal government stepped in to appease the mob. The constitution does say something about double jeopardy, but that never prevented me from indicting someone under federal law when state charges could arise from the same set of behaviors. The officers were convicted under federal civil rights statutes.

They should NOT have beaten King that way. They actually cracked his skull.

If someone is trying to kill you, you have every right to hit them in the head with a stick. If they are not–and Rodney King was not–you can hit them on the thigh or the arm, but NOT on the head.

The meaty part of the forearm is considered an effective strike zone, as is the back of the calf and the side of the thigh about a hand-width above the knee. The latter is called a peroneal strike, as it targets a bundle of nerves, including the common peroneal. Theoretically, peroneal strikes should take a man to the ground.

It doesn’t always work. Brad L, one of my fellow Firearms & Defensive Tactics instructors at HSI, once struck a combative subject numerous times in the peroneal, hard, with zero effect. Brad is a former Marine, who does Cross-fit training. He was putting everything he had into it, and hitting in the approved location on the subject’s leg, but the bad guy just wouldn’t go down.

If a baton is properly and judiciously applied, testimony regarding the strikes might sound something like this:

Plaintiff’s attorney: “How hard did you hit my client?”

Officer: “As hard as I possibly could, sir.”

Plaintiff’s attorney: “Why did you hit him that hard?”

Officer: “Because I didn’t want to have to hit him again.”

Make no mistake: the one person with absolute control over what happened to him was Rodney King. If he had pulled over and done his field sobriety maneuvers and spent some time in jail, he would NOT have been beaten, and his name would not have become a household word.

If King had killed somebody (including his passengers) with his car, trying to run from the police at 117 mph, it would not have warranted a national news headline. Idiots driving drunk murder over 10,000 Americans every year (including hundreds of children)–and your family might be next.

The beating permanently damaged King physically and psychologically, but it also made him far richer than he could ever have become stealing from Korean store clerks after beating them with a piece of rebar. The jury in his civil suit against LAPD awarded King $3,800,000 (+ $1,700,000 to cover his attorney’s fees) of the tax payer’s earnings.

King and Lawrence J. Spagnola corroborated on the aforementioned autobiography, The Riot Within: My Journey from Rebellion to Redemption, which you should read if you want to know his perspective on the beating. On 17 Jun 2012, King drowned in his own swimming pool after doing a little too much alcohol, cocaine, and PCP.

I was just getting in to civilian law enforcement in the early 1990s. After the Rodney King circus, I guessed that as a cop, if it was a borderline call between hitting somebody with a stick (oops–I mean, a baton) or a flashlight, and just shooting them, I’d be less likely to go to jail if I chose the latter.

Malice Green

Important safety tip: if you want your kid to have a promising future, you might want to name him something other than “Malice.”

Maybe his mom could tell right away, like the head nurse in that song by George Thorogood and the Delaware Destroyers. Or maybe his mom named him something nicer and he changed his name to Malice to reflect his outlook. I don’t know.

Malice led a troubled life.

He was an unemployed steelworker when two officers with flashlights in hand caught up with him on 05 Dec 1992, outside a crackhouse in Detroit. He reached under the seat of his car and grabbed something.

Malice had a knife on his person, but that wasn’t what was in his hand. He had a vial of crack cocaine in his hand. The cops couldn’t know that, because he refused their commands and would not show them what he was holding. There was a struggle of some kind (accounts differ) and one of the officers struck Malice repeatedly in the head with his flashlight.

Unlike King, they did not crack Green’s skull. But they hit him hard enough to cause bruising in the brain. When you get a bruise on your arm, it swells up. If the bruise is under your skull, the swelling has no place to go, and it crushes your brain. Green died.

Like King, Green should NOT have been beaten over the head with a blunt object. Like King, it SHOULD not have happened. Like King, it WOULD not have happened, if he’d just shown them what was in his hand, turned around, and allowed them to cuff him.

On most departments, before Green was beaten to death, it was not against policy to use a flashlight as a baton. The problem in Malice Green’s case was not that he was hit with a flashlight, but that he was hit on the head with a blunt object in what the jury believed was a non-deadly force situation.

Speaking of the jury, I have not yet told you what color Malice Green was, because it’s irrelevant to the use of force.

I have sat (or stood) through literally thousands of pre-operational briefings. In one outfit, we called them “Guardmount.” When I worked for a city PD it was “Roll Call.” In the Patrol we called it “Muster.”

At one Guardmount, I was told to be on the lookout (BOLO) for a stolen yellow Pontiac with license plate thus and such (which wound up being my first felony collar). In some Roll Calls, we were admonished that break-ins were becoming more common in the warehouse district, and to increase our patrols in that area. At Muster, the sensor guys would tell us of current smuggling trends, and where the latest sensors had been placed.

Those sensors detected minute seismic disturbances. They did not tell you what color the person walking down that trail was. Same with our radar guns. The ones I was issued only told you what speed that car a quarter of a mile or more away was traveling. Despite all the “Critical Race Theory” rhetoric to the contrary, I have never, ever, sat through a law enforcement briefing in which we were encouraged to go out there and make life miserable for persons of color. I have often been told to be safe out there, but never, ever, ever has the shift sergeant said, “. . . and whatever you do, lets try to kill us some black people tonight.”

Malice Green was black. The officers who beat him were white.

Fearing a Rodney King style insurrection, the mayor of Detroit promptly had the two officers who beat him arrested and tried. He even managed to get a member of his staff onto the jury. During breaks, that staff member made sure the jury got to watch Spike Lee’s 1992 movie Malcolm X, which contains some of George Holliday’s video footage of the Rodney King beating.

I love Denzel Washington, who played the title character. Awesome actor. Angela Bassett, too. Apparently the jury did as well, becasue they watched Malcolm X twice during the Green beating trial.

That jury was not composed of those cops’ peers. Not because of their color, but because I’m willing to bet not one single one of them had ever worn a badge, walked a beat at night, or patrolled a crime-ridden neighborhood and been tasked with hunting down and arresting criminals who do not want to go to jail and might even kill to keep from going back to jail. Every single time I have tried to do my civic duty by answering a jury summons, I got weeded out during jury selection because I have worked in law enforcement. So has my wife, for being married to a LEO.

Both of the officers who beat Green were convicted and jailed. Perhaps they should have been. I don’t know, because I wasn’t there when it happened, and I was not given all the evidence the jury was given.

Whether or not Green’s beating was racially motivated, whether or not the subsequent trial was racially motivated, whether or not the jury was racially biased, the conviction of those cops and the lawsuit against the department moved law enforcement policies against the use of flashlights as impact tools. Key words for your purposes: law enforcement policies.

It didn’t matter to Green whether his skull was getting bashed by a flashlight, a baton, or a table lamp.

What mattered to Green, and what should matter to you, if you are deciding to use any blunt object for physical force or deadly force, as dictated by the totality of circumstances as a reasonable person would perceive them at the time, is where the blows are landing.

Get Real

In the movies, people get hit on the head all the time. It always knocks them out with one blow, and they always wake up in the next scene, with no apparent side effects other than a mild headache. In real life, one–even several–blows to the head will not necessarily knock someone out, although even one blow to the head can cause a subdural hematoma that will cause permanent brain damage, and perhaps even kill them eventually, if not treated promptly.

The treatment–drilling through the skull to allow the fluid to drain–is rife with potential for brain damage or deadly infection.

After the Green case, most departments changed their policies; flashlights could not longer be used as impact tools, except in deadly force situations.

“Tonks”

For many years, the US Border Patrol required that applicants be at least 6 feet tall and have all their teeth.*

No idea about the teeth thing . . . Maybe it had to do with image, which can be important. We tend to think that a cop in a clean, pressed uniform is somehow more competent than one who looks like he slept in his.

The 6 foot tall rule reflected a certain reality: BP agents must sometimes arrest dozens of people by themselves, usually in very remote settings, far from backup. The Border Patrol was a much, much smaller organization when that rule was in place. A lone agent needed to be able to cow a crowd that greatly outnumbered him (always a him in those days) through intimidation.

It could be dangerous for the agent, and even for some of the aliens, if an instigator among them pointed out that they vastly outnumbered him and “He can’t take us all.” Agents learned quickly that if one suspect started talking smack, you needed to come down hard on him before the others got any ideas–for their safety, and the agent’s.

Again, we’re talking about the old days here. A whack over the head usually quieted the guy down, and got the message across to the others not to try anything.

Once, when I was a brand-new BP agent, several aliens ran from us, and we gave chase. My journeyman (these days we would call him an FTO, or Field Training Officer) yelled something in Spanish that I didn’t understand. They all came to a screeching halt, and surrendered. “What did you say to them?” I asked, wondering what magic spell could engender such immediate compliance.

“I told them that if they didn’t stop running, the first guy I caught, I was gonna kick his ass.”

If an instigator was inciting a large group to fight, and it was dark, the most convenient tool in hand to whack him was a flashlight. This led to a sardonic joke. They started calling illegal aliens “Tonks,” for the sound a flashlight makes when it hits a head.

By the time I joined the Border Patrol, three and a half years after Malice Green died, using a flashlight as an impact tool was officially verboten, except in lethal force situations.

If the situation was so dire that you were morally and legally justified in shooting someone, you certainly were authorized to whack them with a flashlight, or any other tool.

Even though it was the stuff of “Old Patrol” legend–I never saw anybody hit anybody over the head with a flashlight–the shorthand term “Tonk” persisted. “The Tonks seem to like that trail that runs around the west side of the IBC pump lately,” for example.

“Tonk” is not a racial epithet. I had it on good authority, from some of the older agents, that flashlights make the same noise whether the head they are hitting is white, brown, black, or yellow.**

Indeed, I’ve run up on groups hiding in the brush on the north bank of the Rio Grande, yelling “¡Sientense todos! ¡Nadie se meueva!” only to be met by bewildered, blue eyed stares from the blond haired aliens, who were Polish and did not understand Spanish.

Contrary to popular belief, the immigration laws are not racist.

They are nationalist.

The only South African I ever deported, for example, was white. She was a beautiful redhead, and I wished we could keep her. But she was an alien (the noun written in the federal statutes created and permitted to remain the law of the land by your elected representatives in Congress, meaning a foreign national, a citizen of another country), living in the United States in violation of the law. The adjective for something that violates the law is “illegal.” Hence the phrase, “illegal alien.” When somebody robs a bank, we don’t play word games and say he is “making an unauthorized withdrawal” to avoid offending other bank robbers.

Border Patrol agents in Buffalo, New York might intercept a lot of illegal aliens from Eastern Europe, imported by the Russian mob. In Blaine, Washington, it might be Asians smuggled by Tongs.

The thriving flesh trade on the southwest border of the United States primarily smuggles people from Latin America–as well as occasional Middle Easterners that Hezbollah imports through Brazil.

Consequently, most of the Border Patrol’s subjects are Latin. But I’ve caught people of just about every creed, culture, and nationality on the north bank of the Rio Grande, or in my subsequent career as a criminal investigator / special agent for the INS, and later HSI.

When I was in the Patrol, we referred to all illegal aliens of all nationalities and cultures (unofficially, of course) as “Tonks.” At first, we found it mildly amusing. Then we adopted Tonk into our rookie vocabulary to sound edgy and jaded, like the more experienced agents. Eventually, we used it because everybody else did–except for our sensitive brown bothers wearing BP green, many of whom had thick Spanish accents, as English was their second language. They referred to the illegal aliens as “Tonques” (accent on the second syllable).

The Border Patrol issued us an expandable side-handled baton to use as an impact tool in less lethal situations. We practiced an extensive kata with the side-handle at the BP Academy, and it was a useful device for come-alongs, but even a compact, expandable side-handle, with its grip at a 90 degree angle from the rest of it, tended to get hung up on branches as you chased aliens and smugglers through the brush.

Most of us wound up not carrying it, eventually. It wasn’t heavy. We just wanted to be more streamlined.

Pepper spray (OC) was lighter, took up less space on your belt, and didn’t hang you up as much when you crawled through a barbed-wire fence. But mostly, OC didn’t look as awful on video if you had to use it.

Edged Weapons

. . . or EWs, are anything that cuts or pokes. Obviously, that includes Bowie knives and swords (surprisingly, still used occasionally), but also screw drivers, ice picks, box cutters, et al. We must discuss EWs here, because crenelated flashlights are, in a narrow sense, edged.

Unlike impact weapons, which can be used for either deadly or less-lethal physical force, the use of an edged weapon is almost always considered deadly force.

If a home invader is in your kitchen, and you have reason to believe he is a threat to your life, you can grab a knife out of the butcher’s block on the counter and stab or slash him with it (or both). If you are legally and morally justified in shooting someone, you are legally and morally justified in stabbing them with a knife.

Unfortunately, as with hitting them with a blunt object, one strike from a knife is FAR from likely to stop their lethal aggression. Once more here, our programming from the movies and TV can let us down. The good guy throws a knife, it sinks in through the German army uniform to the hilt, zero blood is shed, and the Nazi sentry immediately falls down without a sound. In real life,

edged weapons can be instantly lethal, with all the attendant moral and legal liability, but are rarely, if ever, instantly incapacitating.

A very well trained knife fighter, using a long enough, sharp enough tool, will incapacitate her or his opponent with a rapid series of slashes to the tendons that enable people to grasp and run. Not something you will be able to pull off with the short, if sharp, crenelations on your flashlight.

In order to get someone to stop stabbing you or bashing you with a baseball bat or dribbling your head off the pavement, if you are instead using your street legal 2.5″ bladed pocketknife, you’ll probably need to stab them multiple times in quick succession. We call that the “Singer Sewing Machine.”

The Singer Sewing Machine can be effective, eventually. If a knife is available and a gun is not, you may have no other choice. But understand, even if it saves your life, the photos they show to the jury will not be pretty.

With EWs, edged weapons, you also need to get and stay inside their arms reach, weathering their blows the whole time. When I boxed with my stubby tyrannosaurus arms, my coach Ty Anderson called that “taking your licks getting in.”

Crenelations on Flashlights

Which brings us to the answer for our question: are crenelated flashlights a good thing, or a bad thing?

The answer is, a little of both.

I believe crenelations first came about as a safety feature. If a light was left on with the bezel (light end) face down of a counter or shelf, you might not be able to see that it was on, and might forget it was. It could eventually overheat, starting a fire or causing lithium batteries (which contain their own oxidixer) to explode.

Crenelations lift the bezel off the surface. Because of the crenelations or gaps, the bezel doesn’t have a “light proof seal” around it. You can see rays of light coming out through the gaps like the spokes of a wheel. Even if you don’t notice, the crenelations allow air to circulate.

Crenelations also change the flashlight’s secondary purpose (the primary being illumination) from impact tool to combination impact tool and edged weapon.

Even the short blade of a box cutter can be deadly if used on a neck, as airline crews found out on 9/11.

If there’s any edged weapon that is not lethal, a crenelated flashlight might be it. The tiny little serrations simply can’t cut deep enough to kill, unless you really work on it repeatedly in the same place. But they can really mess up the soft tissue on a rapist’s face.

Pain Compliance and Psychological Stops

No doubt the cuts from being bashed on the cheek with a crenelated flashlight are painful. The more pain you cause a suspect who is trying to kidnap you, the more likely it is that he will give up and go rape someone else.

However . . .

When someone is amped up on the adrenal chemicals we commonly call “adrenaline,” they don’t feel as much pain. They might not notice pain at all, in the heat of the moment. This is good if the person not feeling pain is you, and bad if it’s the other guy.

3 Ds

Pain compliance does not work as much on assailants who are drunk, drugged, or deranged. Unfortunately, people who are not drunk, drugged, or deranged are less likely to attack you.

The Sight of His Own Blood

When I was a young boy scout, we stupidly thought it was a good idea to sled down a snow covered hill near Tehachapi, California, that had a fence at the bottom. One of my fellow scouts hit the fence hard, cutting his scalp. He seemed to be OK, and said he was, till somebody pointed out that he was bleeding. He touched the spot on his forehead that was stinging a little. He pulled his hand away and saw blood on his glove.

Suddenly, his expression changed.

He ran screaming all the way back to camp.

Showing somebody their own rich red blood can take some wind from their sails, psychologically. There are documented cases of people who were shot with non-lethal, sometimes not physically incapacitating, wounds, passing out on the spot and even dying. We call that a psychological stop. If you shoot me in the foot, I’ll probably fall down and scream to Jesus.

But there are also documented cases of “determined opponents” who have an almost zombie-like countenance. An Islamist extremist on a stabbing spree in a crowded mall might see his own blood and smile, knowing he’s on his way to Paradise, and redouble his efforts rack up the body count in his last moments on earth.

Does this mean that we should not bother causing the bad guy pain, or bloodying his face?

Of course not. It might give you an edge. If nothing else, it leaves his easily found DNA at the scene.

Just don’t count on it working on him like it would work on me. I’m a total wussy when it comes to pain and my own blood. Maybe you are too. In The Book of Five Rings, the great Samurai swordsman Miyamoto Musashi warned of the dangers of assuming the bad guy thinks like you do.

As I see the world, if a burglar holes up in a house, he is considered a powerful opponent. From his point of view, however, the whole world is against him; he is holed up in a helpless situation. The one who is holed up is a pheasant; the one who goes in there to fight it out is a hawk.

–from “Becoming the Opponent,” in The Fire Scroll (Thomas Cleary translation, p. 40)

The Bottom Line on Crenelated Flashlights as Impact Tools

If you are a man–especially if you are a big man–when a guy in a bar breaks a bottle on a counter and starts swinging at another patron, you might be morally and legally justified in whacking the aggressor in the face with your flashlight, while the target of the attack wrestles with the bad guy over the broken bottle.

However, if the flashlight is crenelated and the bad guy’s face looks worse than the victim’s wounds, a jury might be inclined to view the incident as “mutual combat” rather than the defense of others.

If, on the other hand, you are a female–especially a petit, young, or elderly female–who is attacked in a parking lot after work, and you mess up your assailant’s face with your crenelated flashlight, a jury is likely to look at his hospital or booking photos and smirk, thinking. “You go, girl! I’ll bet that schooled him!”

He need not be armed. If you are female, and a guy who is as strong or stronger than you is dragging you by your elbow to his car, no jury in the land (except, maybe, in California or Massachusetts) will hold you at fault for bashing him hard in the nose with your flashlight, crenelated or not.

Final Logistical Consideration

Some crenelated flashlights have sharper serrations than others. IF you choose to carry a crenelated light, be mindful that they can pinch or even cut you when you bend over, or cause wear and tear (literally, tear) on cover garments. You might want to get a flap-over belt pouch or some such to carry it in.

–George H, lead instructor, Heloderm LLC

*Appendix I: About Having All Your Teeth

Later (I believe during Jimmy Carter’s presidency), Civil Rights activists challenged the “6′ tall, all your teeth” requirement, stating it was not a BFOQ for being an effective Border Patrol Agent.

In Equal Employment Opportunity, a BFOQ, bona-fide occupational qualification, is a permissible form of discrimination for hiring one type of person over another.

Fighter pilots, for example, must be in a certain height range. The pilot must be able to see over the instrument panel. Her or his feet must be able to reach the rudder pedals. But they can’t be so tall that their helmet hits the canopy. There is only so much room in a cockpit, only so much adjustment in the height of an ejection seat, we can only move the rudder pedals so far forward or backward. My height and the length of my legs barely made the BFOQ cut. Others were not so fortunate, but short (and overly-tall) people are not a protected class under federal civil rights statutes.

Hooters restaurants serve bar food. It’s not bad as bar food goes, but the type of customer Hooters’ business model aimed to attract was not overly concerned about fine cuisine. Like many businesses in Japan, Hooters’ business model was to make money from primarily heterosexual male (or occasionally, homosexual female, or bisexual) clientele who preferred the ambience of an attractive female server pretending to be amused by their jokes. Thus, being young, female, attractive by popular contemporary standards, and shapely was a BFOQ for Hooters wait-staff (I understand that was later struck down by a court).

In the early 1980s, a young and otherwise well qualified man sued the Air Force Academy under civil rights statutes. He’d been denied admission after a physical revealed he had sickle-cell anemia. With sickle-cell, the red blood cells cannot transport oxygen as well as normal RBCs which are Frisbee shaped. Only black people can get sickle-cell, so the young man’s lawyers argued that screening out applicants who had it was a discriminatory hiring practice.

The Department of Defense countered that cadets at the Air Force Academy must undergo physically strenuous training at 6000 feet above sea level. Being able to carry sufficient oxygen was not only a BFOQ, it was essential for survival through the rigors every cadet, male or female, black, white, yellow, brown, or red, went through. I’m white, but my blood, which always runs a little anemic, almost disqualified me (I’m often turned away at Red Cross blood donation centers to this day, for the same reason). Unlike the unfortunate black applicant, who could not change the shape of his red blood cells and lost his case, I was able to get produce more RBCs by switching from a primarily pizza and yogurt diet to liver, spinach, and other high-iron foods.

Most of the Border Patrol’s work is along the Southwest Border (drugs move across both borders, but the distribution of wealth is far better balanced in Canada, and as a result, most Canadians are not desperately seeking better economic opportunity in the USA). Hispanic Americans, many of whom grew up bilingual, had a lot to offer the Border Patrol, but were denied entry by the 6 foot tall, all your teeth requirement.

They argued–successfully–that brawn and perhaps even height conferred certain advantages when one is outnumbered by those one is arresting, but that having all your teeth was not a BFOQ. It excluded a large number of Latin applicants, who might not have had access to quality dental care growing up. As did the height requirement, since the descendants of Conquistadores and Native Americans tended to be shorter than the descendants of Vikings. The court agreed, and now, a very large percentage of Border Patrol agents are Hispanic. Many bring invaluable knowledge of the culture, mores, and languages of the people they are policing into the Patrol with them.

**Appendix II: DFWI

Red is not in that list because the Border Patrol has a “hands off” policy regarding Native Americans of the trans-border region, at least when it comes to nationality determination.

Believe it or not, the Border Patrol does not just enforce Title 8 of the United States code, our nation’s immigration laws. Certainly the vast majority of their arrests are for illegal immigration, just as the vast majority of a highway patrol officer’s tickets are for moving violations.

In Arizona, the highway patrol is called the DPS, the Department of Public Safety. We jokingly call them “the Department to Prevent Speeding,” but of course the DPS does far more than write tickets. They patrol rural stretches of road–not just the freeways–far from civilization. Troopers assist at accident scenes, and save many lives. They look for lost elderly drivers and kidnapped kids. In some smaller towns, highway patrol officers are often the ONLY law around, especially in counties where most of the sheriff’s deputies are essentially city cops, patrolling the unincorporated periphery of a municipality, leaving the rest of the county practically unguarded.

Similarly, BP agents patrol the border region. They are often the only law enforcement around, or a lone deputy’s only LE backup. Some states and counties cross-designate BP agents as Peace Officers, specifically because BPAs are often the only law (literally) West of the Pecos–or east of it. BPAs look for and render medical aid to lost hikers in Big Bend National Park. They back up Park Rangers in gun battles with bandits in Organ Pipe National Monument and the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge. Border Patrol assists at scenes of accidents, disorder, or emergency.

Once, on the old military 2 lane that parallels the Rio Grande northwest of Brownsville, I rolled up on the scene of an accident. The drivers, two middle aged Tejanas, were not seriously hurt, but were about to come to blows.

As someone who got most of a minor in Anthropology, I can tell you that there is far more variation in individual behavior within any given culture than between cultures. We are all, after all, individuals (except for that one guy who said “I’m not” in Monty Python’s Life of Brian). But it’s not stereotyping to say that within any given culture or subculture there are expected norms.

In many Latin American cultures, it’s not unexpected–indeed, it is considered normal, acceptable, and even encouraged–to have an effusive outpouring of emotion after an accident, tragedy, or dangerous experience. My Latin friends call it “Mexican Hysteria.” In this case, the two women were a little shaken up by their accident, but that was expressing itself in raised voices and raised fists.

I intervened between them, facing the one acting the most agitated, saying “Calmense” and “Tranquilo” in as soothing a voice as I could muster. She suddenly collapsed into my arms, sobbing into my ballistic vest.

Just then, several of my coworkers, leaving a fundraiser golf tournament for the families of fallen agents, drove by.

I got no end of flak from them afterward.

During the aforementioned Rodney King riots, arsonists began to shoot at firefighters to keep them from undoing the arsonists’ destructive work. The Border Patrol sent about 400 agents to help contain the insurrection. Heloderm instructor Greg G was one of them.

I’m told some of the Border Patrol agents “rode shotgun” on fire trucks with BP issued rifles during the LA riots. Mostly they rode around in two agent radio cars. Greg remembers that the issued M16A1 he carried during the Los Angeles insurrection was made by the Hydramatic division of General Motors.

About 20% of Arizona’s border with Mexico is on the Tohono O’odham Native American reservation. A great deal of drugs are run through the reservation, and not surprisingly, many of the facilitators on this side of the border are Native American. It is, after all, happening in their yard.

A Border Patrol special operations commander was interviewed about this Wild Wild West action by a national periodical. When asked for percentages, he replied, quite correctly, that most of the persons BP catches running drugs out of the reservation are Native American. Of course the magazine got it wrong, quoting him as saying that most of the Native Americans on the reservation are running drugs.

That gaffe was not nearly as famous as Rob Pittenridge’s quote in the news media. Rob was a Shadow Wolf, a member of a small, elite US Customs unit tracking bandits in SW Arizona. All Shadow Wolves are Native American. Although white, brown, yellow and black people can learn to track, and have become very successful trackers, being at least part red is a BFOQ for the Shadow Wolves, who patrol the Tohono O’odham Nation.

Rob was quoted in a national publication as saying that even though the FBI had jurisdiction over violent crimes committed on the Res, “The FBI couldn’t track a menstruating elephant through a snow bank.”

Later, I worked with Rob in internal affairs. He had a Newton – Azrak award on display in his office. Newton – Azrak is the Border Patrol’s highest award for gallantry. Rob got his by crawling into a burning car and pulling out a family near Wellton, AZ.

When I asked Rob if he’d been misquoted by the media, as so many are, he replied that for a change, they got it exactly right.

Word for word.

After the Federal Law Enforcement re-organization which created the Department of Homeland Security, the Shadow Wolves were placed in Customs and Border Protection, along with the Border Patrol. Many of the Shadow Wolves resented their association with the Border Patrol, whom they mostly viewed as glorified immigration officers. As far as Native Americans were concerned, the non-native Americans are the illegal immigrants.

Throughout history, and pre-recorded history, different Native American tribes lived and hunted in different areas. Those areas changed over time. Periodically, they moved in and displaced other Native American groups. When the US and Mexican governments negotiated the Gadsden purchase, they drew the line right through the middle of territories then occupied by aboriginal peoples, who then became either “Mexican” or “US” citizens with the stroke of a pen. The same thing happened to Native Americans of the Northern Plains, who might find themselves as US citizens or subjects of the Queen, depending on which side of the 49th parallel they were on when that line was drawn in 1846.

Nationality law is the second most complicated set of federal codes (the only federal statutes more complex are the admiralty laws). When learning the convoluted ways that a person can derive US citizenship, Border Patrol Academy cadets encountered “DFWI” in capital letters. A little farther on, in the same Nationality textbook, they might read the phrase “Again, DFWI.”

Figured it out yet?

It was shorthand reminding young Agents that it is neither polite, nor prudent, to dig too deeply into the “nationality” of Native Americans.