“Nobody called off the war!”

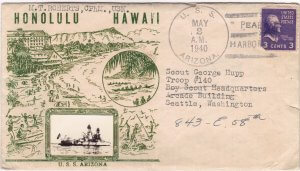

Daniel K. Inouye was a 17-year-old high school student living on Oahu, Hawai’i, on December 7, 1941. When he heard on the radio that Pearl Harbor was under attack, and saw the smoke from the burning ships and the Japanese planes flying overhead, he raced over to Pearl Harbor as fast as he could to help.

Think about that.

Most reasonable civilians would be staying as far away from the falling bombs as possible, perhaps even “heading for the hills.” But Dan Inouye and others like him were citizens. I’m not talking about nationality, or what side of some arbitrary line on a map you were over when you popped out of your mom. When I say “citizen,” I’m talking about a person who feels a part of their community and helps others in their community, even at personal risk. Blowing your leaves into a neighbor’s yard is NOT citizenship. Helping an old lady down the stairs of the burning World Trade Center on 9/11 instead of running for your life is citizenship.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese planes attacked Pearl Harbor repeatedly, in “waves.” Inouye helped at a first aid station that had just been hit.

In 1942, as soon as he was old enough, Inouye volunteered for the military. But he was turned away, classified “4C.” Eligibility for military service was rated on a scale. “1A” was fit for service. “4F” was ineligible due to a medical problem. “4C” was ineligible as an “enemy alien.”

Daniel Inouye was a US citizen. But after the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl harbor, descendants of Japanese were viewed with suspicion. The US rounded up thousands of Asian Americans and stuck them in detention camps. Americans with German or Italian accents might have been looked at askance, but they weren’t rounded up en masse and put in camps.

Daniel Inouye and the other Japanese in Hawai’i were not rounded up–they were a high percentage of the population, and putting them in internment camps probably would’ve collapsed the local economy. Despite Pearl Harbor, the government of the Hawai’ian territory was far less fearful of those with Japanese ancestors than the majority of the mainland US population was.

Inouye and other Japanese Americans petitioned the president of the US to be allowed to serve. Eventually, they were permitted to don the uniform of the United States Army.

The Nisei (a Japanese language word meaning persons of Japanese descent born outside of Japan) were assigned to the European Theater of Operations (ETO) to fight Nazis. That was partially to prevent issues of divided loyalty (federal agents who grow up in trans-border regions are today sent to interior offices to limit cross-border graft), and to spare any the grief of discovering they had killed a cousin, but also to limit “Blue on Blue” from cases of mistaken identity, and to prevent infiltration by actual enemies in the Pacific.

Inouye and his brothers of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team fought in Italy and in France before being sent back to Italy for the final push against the Germans’ nearly-impregnable Green (Gothic) Line. Along the way, Inoyue was promoted to sergeant, and then got a battlefield commission as an officer.

On 21 Apr 1945, Inouye was shot through the stomach but continued to fight. He had taken out two enemy machine gun nests, and had just pulled the pin of a hand grenade to throw into a third, when an enemy soldier shot a rifle grenade that hit Inouye in the elbow, blowing off most of Inouye’s arm–the arm with the hand that had been holding the grenade.

Inouye went down, fishing around desperately for the grenade. American hand grenades had a spring loaded lever, called a “spoon.” The hooked spoon flying up and off is what started the fuse. The spoon was held in place by a pin–the pin Inouye had already pulled out.

Soldiers were trained to place the spoon in the web of their palm as they pulled the pin, keeping the spoon from flying up and off till they threw the grenade. Inouye fished around desperately, expecting the grenade to be somewhere on the ground near him. His men started crawling toward him to help, but Inouye ordered them to stay back, fearing the spoon had flown and it would explode at any second. Then he found the grenade. Along with the spoon, it was still clenched tightly in his former hand.

With his remaining hand, Inouye pulled the grenade out of his now lifeless hand and tossed it into the enemy bunker, silencing the machine gun nest. Then Inouye got shot in the leg, and finally passed out. His men dragged him down the mountain to a casualty collection point. When he woke to find them huddled around him, he was grateful, but he chastised them for leaving their positions. He ordered them to get back to the assault. “Nobody called off the war,” Inouye said.

You may need to slap a tourniquet on in a hurry, but even after you do, your war may not be over. You need to know now, before that happens, that despite the pain and discomfort you can still run and carry friends and fight if necessary to survive and to help others to survive.

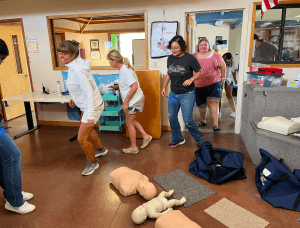

If a tourniquet is not applied so tightly it feels like you are pinching the limb off, you are doing it wrong. In our first aid classes, while students are experiencing that excruciating pain, we have them get up and move around, so they know it can be done if necessary to save their lives.

This does more than just build confidence. It’s also our slightly subversive way of combatting the general wussification which is pervading our society in this sensitive era of helicopter parenting, when kids grow up playing with their thumbs on the couch instead of running around outside and scraping their knees, like they should be.

Inouye was wounded at about 1500 hours (3 pm). It was close to midnight when he got to an aid station. Inouye was triaged as Expectant–expected to die. A chaplain came to comfort him. “God loves you,” the chaplain said. “I love God too,” Inouye replied, “but I’m not ready to see Him.” The docs, surprised that he was still alive, took him into surgery. It took 17 transfusions of blood to keep Inouye alive–every single pint donated by black soldiers of the 92nd Division. In an era when Blacks were not legally allowed to drink from the same water fountains as Whites in many states, allied soldiers of every color were proud to donate and grateful receive life-giving blood. They weren’t too picky about whom it was going to, or who it came from.

After his honorable discharge, Capt Inouye obtained his Law degree on the GI bill. He later served as President Pro Tempore of the Senate, a position third in succession to the President of the United States. His half century of public service was notable for his bipartisan record. In other words, Senator Inouye voted his conscience, rather than in lock-step with his party. That’s what happens when we elect people like Dan Inouye, who had demonstrated beyond any doubt that he chose selfless service over self-interest.

The US Navy now has an Arleigh Burke class destroyer, DDG-118, named after him.

Most of this post originally appeared in the password protected training summary for a Spring 2025 Pediatric First Aid Class.