Philippine Bolos and Spanish Bolo Bayonets

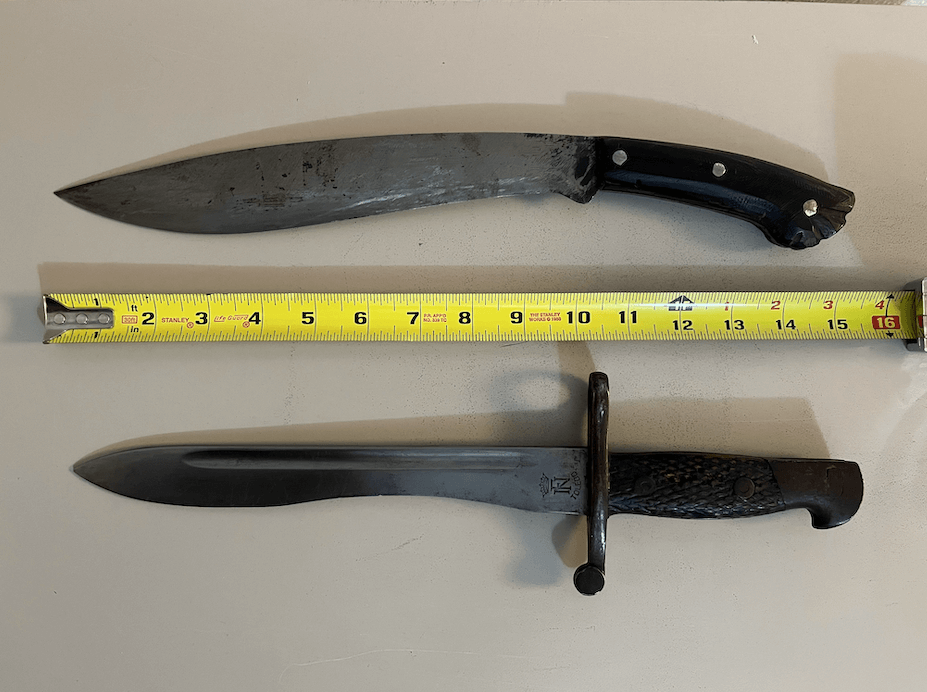

The bayonet on the bottom of this photograph is a Spanish Modelo 1941.

My father probably picked up the hand-crafted knife above it while he was undergoing jungle survival training in the Philippines, at some point during his three tours as an F-4 pilot in Southeast Asia.

The people of Palau call Filipinos chad ra oles, “people of the knife.”

Edged weapons have always been a huge part of Filipino fighting arts. The Moros of the southern Philippines preferred fighting with the wavy, roughly 18″ bladed kris (above) and the kampilan, a longer, double edged, two handed sword (Whitehead, p. 290, and Fulton, p. 127), although they had many different styles of blade.

The bolo

Even before they were colonized by Spain in the 1500s, the peoples of the 7000+ island archipelago that came to be known as the Philippines used forward curving, heavy bladed knives with cutting edges on the inside of their curve to farm, hack paths through the jungle, and chop coconuts.

Filipinos speak many different languages. In Cebuano, this ubiquitous farm and fighting implement is called a sundáng. In Hiligaynon, it’s a binangon. In Tagalog, it’s an iták.

The Moros of the southern Philippines carried a fatter version called a barong.

In form and function (mostly function), it’s not entirely unlike a Malasian / Indonesian parang. Its distant cousin is the Nepalese khukuri.

The Spaniards and the Americans called them bolos.

It’s unclear what influence, if any, the straighter bladed Spanish machete had upon the development of the bolo, and vice-versa. But the dropping point (more or less in line with the thrusting arm of the wielder) and heavy bellied blade of a typical bolo make it both a lethal stabber and a hacker.

Three Types of Edged Weapons Strikes

It’s instructive here to differentiate between hacking, slashing, and thrusting.

In 1884, Richard F. Burton observed that “. . . the cut wounds and the thrust kills” (The Book of the Sword, p. 255). This is generally true, but perhaps an oversimplification.

When I fenced at the Air Force Academy, Capt Worsdale, the JV coach, tried to keep us on point–literally–when lunging (thrusting). We could parry with our foils, but not swashbuckle. “Enough with the hack ‘n’ slash,” he would say in his Northeastern American English, nearly devoid of Rs. “That’s gahbage. Get rid of it!”

And Worsdale was right, of course–if one is fencing with a foil, or reaching past your co-conspirator to puncture Francisco Pizarro’s neck with the tip of your rapier.

John Styers, who codified the USMC’s bayonet fighting style in his 1952 instruction manual Cold Steel, called a smashing parry (what Capt Worsdale called “hack”) the beat.

But when using an axe or a bolo or a khukuri directly on a coconut or an enemy’s head / neck, it would best be described as a chop.

The chop might be followed by a drawing slash, but the slash is an add-on, a nuance, not the main coup. A chop with a bolo was every bit as lethal as a thrust–as many Spaniards (and later Americans, and then Japanese) in the Philippines found out the hard way.

“You develop a style without a style – chop, chop, chop.”

–Filipino escrima master Leo Giron, quoted in Mark Wiley’s Filipino Martial Culture (by Mallari)

So respected were the Filipino bolos, that the Spaniards copied the idea and carried it throughout their empire. The bolo remained, even as the Spanish withdrew from the PI and Latin America. Pancho Villa was said to carry a bolo.

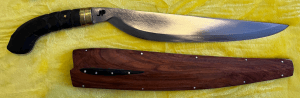

When sheathed at all, rather than just stuck in a belt, bolos tended to be encased in wood scabbards. These were typically made of two slices of hardwood pinned together around the edges.

Bolos Past and Present

The Greek kopis

The concept of a broad, single edged, leaf shaped blade with a forward curve to the point, the spine on the outside of the curve, and the cutting edge on the inside, is far from new. The ancient Greeks called it a kopis (Burton, Book of the Sword, p. 236). The Etruscan (pre-Roman) civilization of the north central Italian peninsula had similar weapons 700+ years before Jesus of Nazareth gave his Sermon on the Mount.

The Spanish falcata

Tribes in the southern Iberian Peninsula (Spain) carried a weapon remarkably similar to the Greek kopis when the Romans invaded in 220 BC. Hannibal’s troops (probably Iberian mercenaries) carried them in the Second Punic war.

Historians have been calling it a falcata (falcon shaped sword) since the 1800s, although that term did not exist in Roman times. The falcata differed from the kopis in that the forward 1/3 or so of the blade was also sharpened on top.

Seneca wrote of a sword that could cleave through a Roman helmet (De Beneficiis 5.24), which he called a machaera Hispana–roughly, Spanish sword. But machaera is also used to describe the short, straight bladed, double edged Spanish sword the Romans adopted as standard issue (the gladius hispaniensis) throughout their armies, as opposed to what we now call a falcata. The Iberians probably had a different word for each.

The Ottoman yataghan (Versak): NOT a Bolo

The Ottoman Janissaries carried a relatively small, S-curved sword called a yataghan (sometimes called a Versak, after the Turkic peoples who made them).

In the late 1800s, swords and bayonets from various militaries were fashioned after the Ottoman Versak sword; they came to be known as yataghan style blades.

Yataghan blades are NOT usually widened closer to the point, as were the kopis, the falcata, and the bolos. Although bolos came in many different shapes and sizes, “A common distinguishing characteristic of the bolo is its blade that widens and curves toward the tip.” (Mallari)

Meet the new boss . . .

Having wrested the Western half of the Continental United States from the Mexicans and the Natve Americans, believers in “American Exceptionalism” continued American expansion and into the Pacific, parts of the Caribbean, and Latin America. The US “won” the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Cuba from Spain in the Spanish – American War at the end of the 1800s, and remained there.

The Filipinos were glad to have US help in ejecting the Spanish, but many were upset that they had traded one set of occupiers for another. The Philippine Insurrection (also called the Philippine – American War), a revolt by many Filipinos against American administration, immediately followed the Spanish – American War.

Bolos at Balangiga

The bolo, if wielded with sufficient skill and motivation at close enough range, is more than capable of doing its job, even against those with rifles. Just ask the troopers of the Company C, 9th US Infantry, who were overwhelmed and almost entirely annihilated by Filipino LtCol Eugenio Daza’s bolo armed insurrectos in Balangiga, on the island of Samar.

“As the soldiers began their Sunday breakfast, the police chief approached a sentry, then suddenly pulled a bolo and cut him down. A mob of bolomen charged out of the church and the tents [in which many members of the local populace had been confined], cutting and slashing the stunned soldiers. [Capt. Thomas W.] Connell and his subordinate, Lt. Edward A Bumpus, were struck down; desperate soldiers fought off their attackers with Krags [rifles], kitchen implements, and even cans of food. A handful of men under veteran noncoms retained their composure and managed to fight their way to the beach, where they set out on a desperate voyage by banca to the closest garrison at Basey. But forty-eight officers and men died in the attack or during the escape.”

–McAllister Linn, pp. 310 – 311

See Appendix to learn the fate of the bells which may or may not have signaled that attack to those in the tents. See The Evolution of Different Trigger Types for more examples of bolo combat (or better yet, read all of The Philippine War and Moroland).

Just about every Filipino household had at least one bolo. Those who worked in agriculture used bolos on a daily basis. When the vast majority of the populace lived literally off the land, it might have been possible to get the impression that each Filipino child was issued a bolo at birth–just as every adolescent Italian male seems to have been issued a Vespa and a lovely lady to tote around on it. According to legendary Philippine martial arts master Dan Inosanto, Filipinos who joined American units were instructed in American close combat methods, until it was realized that the bolo fighting styles they already knew, having grown up with one constantly at their sides, were far more effective (Mallari). The only thing harder than learning a new art or habit is UNlearning an old one, so why change what works better?

“In hand-to-hand combat our soldiers are no match for the Moro. If our first shot misses the target, we rarely have time to get off another.”

–Capt Cornelius Smith, Medal of Honor recipient (Fulton, p. 111, quoting from C. C. Smith Jr’s Don’t Settle For Second, p. 48)

The American military, having learned of the bolo’s effectiveness from the receiving end, issued bolos in both world wars, primarily (but not exclusively) to medics. American issued bolos had broader, more leaf-shaped blades similar to the Philippine Moros’ barongs (also spelled borongs), which looked like a cross between the elegantly curved bolo of the northern Philippines and a broad western meat cleaver (Whitehead, p. 212).

I chose not to italicize the word bolo in this article, as it is now commonly used in English to describe a variety of Philippine farming and fighting implements.

Henry Johnson’s bolo

On the night of 15 May 1918, then-Private Henry Johnson and Private Needham Roberts of Company C, 369th Infantry, 93rd Division, AEF were on sentry duty when they spotted at least 12 German trench raiders approaching.

Both sentries were wounded. Despite multiple injuries, Johnson leapt out of his position and attacked the Germans, cleaving through the skull of at least one with his bolo, repulsing the attack.

Bolos in WWII

Bolo-armed Filipinos fought a guerrilla campaign alongside Americans against the Japanese occupation during the second World War.

Rifles (primarily M1917s, the “American Enfield” made at Eddystone) were more plentiful among the Philippine Scouts and other native fighters in WWII than they had been at the turn of the century. But just about everybody, American and Filipino alike, also carried a bolo or barong as standard equipment, according to guerrilla memoirs like Whitehead’s and Richardson / Wolfert’s.

Before the war, Arthur Whitehead had been an officer in the 26th Cavalry Regiment of Philippine Scouts, which was well armed with modern M-1 Garands and M1911 .45 pistols. Officers and enlisted troopers alike carried the .45s, which they practiced firing at man-sized silhouettes from horseback (Whitehead, p. 44). After Whitehead escaped from Japanese occupied Luzon, he joined the 63rd Infantry Regiment on Panay, and formed a horse-mounted scout unit:

“Each cavalryman carried a [M1917 Enfield type] rifle over his shoulder, a long bolo on his belt, and a light blanket with uncooked rice and a mess kit around his middle.” (p. 141)

While scouting the nearby island of Negros in search of horses, Whitehead noted that the commanding officer on Negros “had fewer troops and less arms and ammunition than we did on Panay. Many of his men were armed with .22 caliber rifles, shotguns, and palteks (a native homemade shotgun with a length of plumbing pipe for a barrel). Some of his companies were armed only with bolos” (p. 142), as were Filipino home guards on Panay (p. 128).

“One time I got clipped with a bayonet. I blocked the samurai sword coming down toward my shoulder, and a rifle bayonet went by my side from another Japanese shoulder [sic from the original article; did he mean “soldier”?]. I cut the hip of the bayonet thruster and then the triceps of the one with the sword. After that I just keep charging and fighting the next ones. It’s up to the guys behind me to finish the job because there are too many more coming.”

–US Army boloman Leo Giron, quoted in Mark Wiley’s Filipino Martial Culture (by Mallari)

The bolo issued by the USMC in WWII had a rounded tip–even more so than the US Army’s M1917 bolo of both World Wars. The USMC bolo was strictly a chopper, thicker and more solid that a butcher’s meat cleaver.

I’m not sure why medics needed this item of equipment (any more than anybody else in the Pacific jungles). One imagines that it could have been useful for hacking field expedient litter and tent poles. I doubt it was used for amputations, although I guess it would have done the job quickly, if not precisely. I have zero doubt that, in extremis (for example the last-ditch Japanese bayonet attack of 07 July 1944 on Saipan), one or two USMC bolos may have split a Japanese helmet, with the occupant’s head still inside.

Bolos in Vietnam

American B-52s flew combat missions into Southeast Asia from Clark AFB in the Philippines during the Vietnam War.

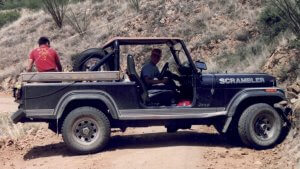

American pilots serving in Southeast Asia went to “Snake School,” jungle survival training, in the Philippines. Many picked up home-made Philippine bolos while they were there. These were often made from the springs of old Jeeps, and had wooden scabbards. Fighter cockpits did not have much room for a machete, so fighter pilots in Southeast Asia mostly carried the shorter (5″) bladed jet pilot’s survival knife when they flew, instead.

After the USAF lost several F-105 fighter bombers to North Vietnamese MiGs, Col Robin Olds and other tacticians of the 8th Tac Fighter Wing came up with a classic bait and switch: F-4 fighters armed with missiles instead of bombs would fly F-105 routes at F-105 speeds and altitudes. When the MiGs popped up through the clouds to attack what they thought were bomb-laden F-105s, they found instead missile armed Phantoms ready to fight. Seven MiGs were shot down with zero American losses that day, 02 Jan 1967.

American pilots had so much respect for the bolos as concealable weapons, capable of surprising the enemy with a lethal close range counter attack, they named it Operation BOLO.

I used to think the FCP (or possibly FCF) stamped on the right side of my dad’s Vietnam era bolo were perhaps the initials of a previous owner who may have no longer needed it. Now I’m pretty sure they were the initials of the Filipino panday (metal smith) who forged it (see JP Blacksmith in pinalingkod below).

When my dad died in the mid-1990s, the hilt his bolo was a light, greyish tan. When I rubbed some linseed oil into the hilt, it turned black. I don’t believe ebony wood is native to the PI; but perhaps there is a similar wood there. Many bolos have hilts made of carabao horn.

Modern bolos

The legacy of the bolo lives on. Muslim Moro tribesmen who fought US troopers in the PI after the turn of the 20th century would have been proud of the motivation, but disappointed by the poor performance of, a radicalized 19 year old Islamic convert who attacked NYPD cops with a bolo or khukuri shaped blade on 31 Dec 2022.

Three officers were injured. The payaso who attacked them was shot and taken into custody.

He clearly didn’t have any clue what he was doing. Any self-respecting Moro on a juramentado would’ve killed at least two of his enemies, and forced the third to completely martyr him, before succumbing to gunfire.

The pinalingkod

This bolo was made recently by JP Blacksmith, which as far as I can tell from their YouTube videos, are from the Philippine island of Bohol, in the Visayas.

Their pinalingkod has a wide, clearly delineated bevel, although it (like the Phrobis M9 bayonet) is only beveled on one side.

Note the JP initials inscribed or stamped just ahead of the hilt’s brass collar. This bolo is hand made, solid, and one serious chopper.

In their YouTube advertising, JP Blacksmith says they got the pinalingkod’s design from their grandfather, so it’s possible that very similar blades were carried by Boholano guerrillas during the Japanese occupation.

Bohol was attacked by the Islamist extremist Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) on 12 Apr 2017.

Spanish Bolos and Bolo Bayonets

As you can see from the image at the top of this article, some Spanish bayonet designs were clearly adapted from the bolo.

Machete Modelo 1907

The Spanish military issued their own bolo knife, ostensibly for artillerymen, the Machete Modelo 1907. It had a 11.75″ blade, and a downward curving pommel. The ends of the cross guard had two large, flat-sided finials offset to opposite sides (forward on top, and rearward on the bottom), giving the straight crossguard an S-curved appearance.

This image of a Spanish M1907 bolo above is from International Military Antiques (ima-usa.com)

A finial is a ball or circle on the tip of a ricasso or cross-guard. I’m not sure if the term would appropriately be applied to the little ball of metal at the tip of many metal sheaths.

Note the similarity between the cross guard of the M1907 to that of the M1894 artillery sword shown earlier in this article.

Machete Bayoneta Modelo 1941

The Spanish M1941 bayonet for Mauser rifles was a shorter (not quite 10″ bladed) version of the M1907 machete, with a straight hilt so it could be mounted to a rifle. The top of the crossguard had a muzzle ring. It retained the long lower quillion with the large, flat sided finial, only the finial is offset to the front (opposite the offset of the lower guard on the Spanish Modelo 1907 artillery machete and the M1994 artillery sword).

One thing I admire about the M1941 is that the hilt and the scabbard are dark, so as not to give away a soldier’s position when it was sheathed. The blade, in contrast, is made of bright shiny naked steel–as a bayonet should be, for full psychological effect.

This particular bayonet was made in Toledo, Spain, a region with a long tradition of blade making excellence. So was the Spanish artillery sword nearer to the top of this article.

When my father was stationed in Europe in the 1950s, he purchased a fine cup hilt rapier made in Toledo. A real one, with a sharp, strong, flexible blade. Many was the cardboard box skewered by that swashbuckling sword when my dad wasn’t looking–especially after I saw Michael York playing “d’Artagnan” in the 1973 – 74 Musketeers movies.

The Modelo 1941 appeared on the scene well after the Spanish Civil War in which fascist Francisco Franco, aided by the Nazis, took power in Spain. Spain was officially neutral in WWII, although Spanish “volunteers” served on the Eastern Front. Unlike, say, a German Mauser or British SMLE or Japanese Arisaka or Russian Mosin bayonet, any given Spanish M1941 probably never got very close to the proverbial Elephant.

The above photo is titled “Corporals at Sidi Ifni.” While it may have been taken before (or after) the Ifni War of 1957 – 58, it’s apparent that Franco’s Spanish forces in North Africa used leftover WWII era equipment, including Mauser rifles and coal-scuttle type helmets, during the West African decolonization wars. The helmets in the photo are probably Spanish M42s or Modelo Zs, copies of the German M35.

A Spanish M1941 bayonet in your collection may have seen action there. Judging from the sparse vegetation in the background, it’s not likely to have been used as a bolo for cutting vegetation, although a soldier cutting branches to camouflage his position might just as well hack as saw.

I used to drive a Jeep Scrambler. I loved that bucket of bolts, although truth be told, it was too long to be a Jeep and too short to be a truck.

Similarly, the M1941 was probably never the bolo it was intended to model. Real bolos came in many different shapes and sizes, but all shared a heavy, thick (and wide) blade that gave them sufficient momentum for chopping. Like my Scrambler, the M1941 was just too light for really effective chopping, and too curvy to be a knife. The blade was too irregularly shaped for common cutting tasks, and probably difficult to consistently sharpen.

That said, I’m sure that machete modelo 1941 staring at you through the glass case of the pawn shop, begging to come home with you, may very well have been a source of comfort for some lonely, cold soldado on sentry duty.

Machete Bayoneta Modelo 1964

You may see this listed as a “Spanish M58 bayonet” in mom ‘n’ pop gun stores or online. That’s because it was made to fit the Fusil de Asalto Modelo 1958, the CETME.

Some of the German engineers who had produced small arms during WWII (including Ludwig Vorgrimier) escaped to Spain after the war, where they produced the CETME rifles, ancestors of the StG45(M) sturmgewehr, and predecessors of the H&K G3. In addition to the CETME, the M1964 bayonet fit on the Spanish FR-7 and FR-8 rifles (see below).

The M1964 bayonet retains some of the curvature of earlier bolo bayonets, but the curve is significantly reduced, possibly in response to complaints about the extreme curvature of the M1941.

The minimalist guard is bolted through the blade / tang junction with two pins. The checkered black scales of the grip are plastic. The pommel is also held on by two pins.

The left side of the ricasso (the flat part of the blade, behind the edge and in front of the hilt) is stamped with the serial number, and the gear-behind-a-sword emblem of the INI, Instituto Nacional de Industria, Empresa Nacional de Santa Barbara de Industrias Militares: loosely translated, “National Industrial Institute, National Business, Santa Barbara Military Industries” (Ezell, Small Arms Today, pp. 179 -80).

The left side of the ricasso (the flat part of the blade, behind the edge and in front of the hilt) is stamped with the serial number, and the gear-behind-a-sword emblem of the INI, Instituto Nacional de Industria, Empresa Nacional de Santa Barbara de Industrias Militares: loosely translated, “National Industrial Institute, National Business, Santa Barbara Military Industries” (Ezell, Small Arms Today, pp. 179 -80).

Much of what I learned about the M1964 came from WorldBayonets.com, an excellent resource for bayonet identification and nomenclature.

The plastic grip is checkered with mild, rounded finger grooves.

Unlike the M1941, the M1964 has no fuller.

This bayonet was also made in Toledo.

The right side of this M1964 bayonet’s ricasso bears the crest of Toledo: an eagle with a crown over its head, and a cross (or cruciform short sword) on its breast.

One unusual feature of the M1964 is that the receptacle for the bayonet lug is a rectangular hole, rather than the inverted T-shaped mortise slot found on most knife bayonets.

In my ignorance, believing a previous owner had butchered it by grinding a divot in the rear 2/3 of the blade, I used this M1964 as a throwing knife for years. Throwing knives is next to useless as a tactical skill, but I enjoy it a lot more than golf.

When I finally got curious about this particular bayonet, I found that the Spaniards had intentionally shaped the blades that way, somewhat like a bolo. That’s why they called it a machete bayonet.

The CETME M1958, a modern assault rifle, was adopted in (duh) 1958, but the Spaniards chose to supplement their limited supply of CETME assault rifles by upgrading their existing Mausers at about the same time. Spanish M1893 and M1943 Mausers (the M1943 is essentially a German ’98) were re-chambered in 7.62x51mm (as was the CETME Model C). They added a flash hider and a bayonet mount to fit the Machete Modelo 1964. The ’93 became the FR-7, and the ’43 (’98) became the FR-8.

These quasi-modern bolt action rifles were issued to home guards. During the Spanish counterinsurgency against Basque separatists (the ETA) from 1959 to 2011, it’s likely that Guardia Civil forces may have secured the sites of bombings, kidnappings, and assassinations with FR-7s and / or FR-8s and / or M1958s. When they did, M1964 bayonets may have been dangling from their belts or even mounted to their rifles.

The Modelo 1964 almost certainly saw service with M1958 CETME rifles in the Western Sahara revolt of 1973 – 75.

If your version of the M1964 bayonet, unlike mine, has smooth grips, a black plastic scabbard, and an oval mounting hole in the pommel, it was made for export. The Guatemalan Army, for example, ordered Spanish CETMEs and M1964 bayonets in 1969 and 1973. Yours may have been issued during the tragic Guatemalan civil war which lasted from 1960 to 1996.

Appendix I

The Bells of Balangiga

This photo shows Bells of Balangiga, which allegedly rang on 28 Sep 1901 to signal the attack (one imagines an insurrecto in the bell tower watching for the Filipino police chief to take out the American sentry, and then hanging all his weight on the rope to the bells), while the American troops ate breakfast. The bells were captured later, when Balangiga (and much of Samar) was retaken (and practically razed). As with the British response to the Sepoy Mutiny, many of those punished in retaliation had little or nothing to do with the massacre of Company C.

The Bells were kept as war trophies at Fort DA Russell (later FE Warren AFB) for a century.

To contemporary American Army troopers, the bells were a monument to their fallen comrades, and a reminder that their deaths had been avenged.

To Cold War missile troops at FE Warren AFB (including me), the Bells were a tangible part of FE Warren’s fascinating history. Before I read Brian McAllister Linn’s The Philippine War 1899 – 1902, I was unaware of the unjust brutality of the retaliatory campaign on Samar. As a member of the American ICBM force, tasked with the somewhat inglorious, however necessary, job of guarding America’s nuclear deterrent arsenal on the windy Northern Plains, the Bells were a proud reminder that one should never mess with the US military.

But to many Filipinos, particularly those on Samar, the Bells were almost sacred, having been taken from a Catholic church, and as symbols of Philippine “David versus Goliath” resistance to more powerful colonial occupation. Similar to “The Wall” in American politics, “The Bells” became a sound-byte substitute for an entire outlook in Philippine politics. One 21st Century Filipino politician ran almost exclusively on a platform of demanding their return.

Return of the Bells had been requested many times during the previous century. It was resisted by US veteran’s organizations well into this century. The vets saw repatriation of the bells as not much different than ripping a gravestone out of the ground and handing it to the dearly departed’s murderer, or at best as another example of cancel culture.

During the Trump administration, the American veterans groups were overruled, and the Bells of Balangiga were repatriated to the people of the Philippines. As I recall the story related to me by the NCOIC of the FE Warren AFB Public Affairs office, the SecDef simply appeared at Warren in person and cut through all the red tape. Within a week, the bells were packaged up and on the way. There was no time to cast replicas of them to remain in the US, as had been the previous plan.

US Special Forces had been working with the Filipinos during the post-9/11 GWOT (Global War on Terror), and still are, combatting the ASG.

Appendix II

The Fencers in That Photo

Junior Varsity fencers during my freshman (4th class, or “Doolie”) year at the AF Academy.

Back row, standing, L to R: Dave Stockwell, Clive Paige, “Wild Man” Cunningham, Steve Visel, Carl “Soviet” Sovenic, Capt Worsdale (in dark blue sweats; pretty sure Worsdale got promoted to Major before I left the Academy).

Middle row, standing, L to R: Assistant JV Coach Capt Avila (in dark blue Class A uniform), Skodis, unk (he punhced out), Martin, Jeff VanHavel (if memory serves, he wound up busting Iraqi tanks from an A-10), Eric Gunzelman (prior enlisted munitions specialist), Greg Anders, Neil Billings, Varsity Coach Capt Bereit (in dark blue sweats).

Front row, kneeling, L to R: Jim “Coops” Cooper, Josh “Hoser” Jose (probably our best with a foil), some snot-nosed punk, Marlene Lopez, Arnie “Barbaric” Farbarik (sabre, probably the best overall fencer on the JV team), Wendell Burke.

Selected Sources

Richard F. Burton, Book of the Sword (Chatto and Windus originally published this in 1884; my copy is the Dover revision of 1987). This was originally intended to Part I of a three volume work; and only covers the development of edged weapons from the dawn of civilization through roughly the Roman occupation of Briton. Sadly, Burton died in 1890 and never published the other two volumes.

Robert A. Fulton, Moroland: The History of Uncle Sam and the Moros 1899 – 1920 (Tumalo Creek Press, revision of 2016).

Perry Gil S. Mallari, “The Bolo: A Filipino Utility Tool and Weapon” (Filipino Martial Arts Pulse, 31 Aug 2009).

Brian McAllister Linn, The Philippine War 1899 – 1902 (University Press of Kansas, 2000).

John Styers, Cold Steel (Paladin Press; originally published in 1952).

John R. White, Bullets and Bolos (originally published in 1928; my annotated version was published by Constabulary Books in 2021). This is a memoir of White’s service in the Philippine Constabulary from 1901 – 1914.

LtCol Arthur Kendal Whitehead, Odyssey of a Philippine Scout (Arizona Lithographers, 1989). This was published in Tucson, AZ and is available from Whitehead’s descendant Leslie Parr, who may be reached at philippinescout315@hotmail.com, or (520) 297-4833.

Ira Wolfert, American Guerrilla in the Philippines (Simon and Schuster, 1945). Wolfert was a WWII war correspondent; the memoir Wolfert co-wrote is of US Navy Lt Iliff David Richardson, who served in the “expendable” Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 3 before its last PT boat sank. Richardson spent the rest of the Japanese occupation fighting on land.