Bowie Meets Hammer: the JPSK

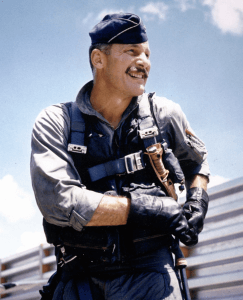

I don’t know who painted this image I pulled off of Pinterest. It features two leaders of men my father flew with over North Vietnam: Chappie James (left) and Robin Olds (right). I believe the painting depicts the aftermath of Operation Bolo, but its hard to tell for sure, because those were some hard-flyin’, hard-fighting, hard-playing fighter pilots, and they frequently celebrated just being alive for another day. One tool that might help keep them alive, should they be downed in the jungle, was the knife on Robin’s survival vest.

The Vietnam War was the hottest manifestation of the “Cold” War. The Cold War, between the USA and NATO on one hand, and the USSR, its Warsaw Pact vassal states, and usually the so-called “People’s Republic” of China on the other, started at the dawn of the jet age.

When my father flew Mustangs in Korea, pilots had survival knives that were, for the most part, left over fighting and utility knives from WWII.

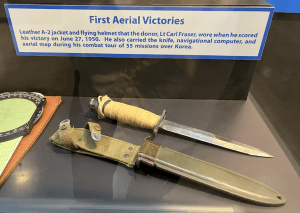

The owner of the M4 (M1 carbine) bayonet above was one of two pilots in an F-82G “Twin Mustang” that shot down a Soviet-built Lavochkin* fighter during the opening days of the Korean war. The string wrapped around the grip was probably in case it was needed for survival tasks.

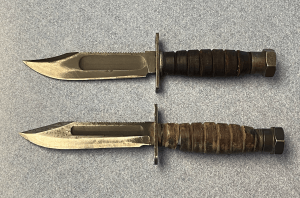

I was a child of the Cold War, but by the time I came around in the early 1960s, the military had procured a knife developed specifically for aircrews: the Jet Pilot Survival Knife (JPSK, sometimes referred to by collectors today as simply a JPK, without the S).

Those knights of the air were, first and foremost, combat pilots. Their lances were the cannons, bombs, and missiles built into or strapped onto their birds. For close-in personal defense, the Smith and Wesson .38 was the officially issued Cold War katana of the sky-samurai. Commonly, their equivalent of a samurai’s short sword was a JPSK.

Actual samurai Miyamoto Musashi famously observed that

“Weapons should be hardy rather than decorative.”

—The Ground Book, in A Book of Five Rings

While form and function are not mutually exclusive, some weapons are longer on usefulness and shorter on looks. A classic example was the USMC Mark 2 utility knife, better known as the Ka-Bar. There’s nothing ornate about a standard-issue Ka-Bar. The design of the Ka-Bar is strictly business (I called my Ka-Bar “NNNO,” for “No-nonsense navel opener”).

If there was ever a more down-to-business weapon than the original USMC Ka-Bar, it was the JPSK.

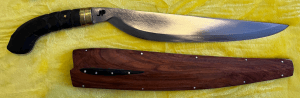

What Americans now call “the rust belt,” from the Great Lakes to Pittsburg and into New England, was once the Arsenal of Democracy, America’s equivalent to the “Street of Steel” in George R. R. Martin’s capital city of “King’s Landing.” One company of very real US armorers was Marble Arms Company of Gladstone, Michigan. When Marble Arms originally designed the JPSK in the 1950s, it had a 6-inch blade. It widened toward the front, nowhere near the broad blade of a Philippine bolo or a Nepalese kukhuri, but every bit a full-bellied, clip point Bowie, in at least its second trimester of pregnancy.

Ejection seats, then relatively new technology, plus an ever-increasing plethora of analog dials and circuit breakers, left little room to spare in jet fighter cockpits.

After some feedback from the aircrews, the JPSK blade was shortened to 5 inches. This gave it a stubbier, even more “practical” (as opposed to “elegant”) appearance. It also, to my mind, moved the center of gravity too far back, which is one reason I never grew overly enamored of the JPSK. Recently, though, a very old and dear friend gifted me one, which caused me to reconsider–and to write this.

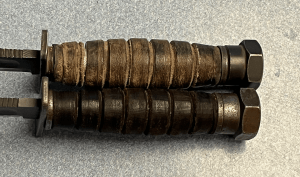

One reason the CG was well aft of the crossguard was the JPSK’s most defining characteristic: its heavy, stout, hexagonal pommel.

Its sharp 120-degree corners were intended to help a pilot who had crashed to bust through canopy glass.

The pommel, about the size and nearly the density of a typical household hammer, could also be used to drive in whittled tent stakes . . . or to bash in an enemy’s head, points out Cecil “Dell” DelRosario, a legendary USAF SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape) instructor who now trains the SERE trainers.

Originally, the back face of the pommel was painted a light (off-white or sky-blue) color. Later, they were painted black. I read somewhere that the paint was for weatherproofing, to keep moisture from seeping into the pommel along the edges of the tang and getting under the leather washers of the grip.

Believe about 20% of what you read on internet forums, but I suppose that weatherproofing logic does pass a smell test, even though nothing (except for, say, neatsfoot oil or some other waterproofing wax applied to the grip) would protect the leather washer handle from absorbing outside moisture, and retaining it long enough to rust and eventually corrode the tang.

I also read that the light color was intended to make it easier to find in the dark. Not sure I believe that. If it’s on your person, where it should be, it can be located by feel (and probably will be, if you are focusing intently on a close-range threat). I suppose if you set it down in the dark, in an evasion situation, you would not want to turn on a flashlight to find it.

One forum I read said the light color was for Navy, and the black for Air Force. Not true. The JPSKs my dad and his fellow USAF pilots wore on their survival vests in Southeast Asia had light colored pommels. I don’t think it was the other way ’round, either (black for Navy / Marine pilots). I believe all JPSK pommels had light paint at first, and they switched to black paint later. But I could be wrong.

Another signature characteristic of the JPSK is the wide fuller with rounded corners. It was wider on the Camillus (‘Nam-era) produced JPSKs than on the later Ontario production models (see below).

The JPSK was, first and foremost, a survival knife. It had two holes in the crossguard to lash it to the end of a stick like a spear to skewer a fish or feral hog. Those holes in the crossguard are out of focus, but easy to see, in the photo of the pommels above.

The business end–the clip-point tip of the blade–was purpose-built strong enough to punch through an aluminum aircraft skin between the spars, should one find it necessary to cut one’s self out of wreckage.

The saw teeth along the spine of the blade can be used to saw wood or to scale a fish.

The saw teeth are sharply angled forward toward the tip of the blade (unlike, say, the barbed tip of an arrow or harpoon, which is angled backward like the swept wings of a jet) so I would think it would be more difficult to punch through aluminum than if the saw pattern was oriented with the tips of the teeth toward the grip side.

While it might be harder to push in, it is easier to withdraw. I believe the saw teeth of the JPSK (and also the aggressive teeth on the spine of the the Glock 81 field knife) were intentionally oriented that way, harder to push into something (or someone), but easier to withdraw, specifically for close quarters, interpersonal, hand-to-hand combat, rather than as a field survival feature. The teeth oriented like the side edges of backwards-pointing arrowheads in a row meant it would be less likely to get stuck in somebody’s ribs. I don’t know if that ever happened with a JPSK, but here is one instance where it happened with a Recon knife.

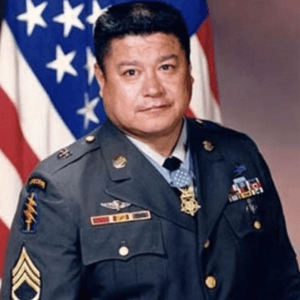

Roy’s Recon

During the Vietnam War, the Counterinsurgency Support Office in Okinawa, Japan procured an unmarked knife for Special Forces operators who had to work in “plausibly deniable” locations such as Laos and Cambodia.

SF MSgt Roy Benavidez was issued one of those “Recon” knives. Benavidez jumped out of a helicopter with ONLY his Recon knife and a medical kit (he was in such a hurry to get there he forgot his rifle and his sidearm) to rescue a team trapped behind enemy lines in a massive NVA bunker complex. A North Vietnamese Army soldier bludgeoned and then bayoneted Benavidez with an AK. Eric Blehm wrote in his biography of Benavidez:

The bayonet blade caught Roy across his left forearm, cutting deeply, but he managed to squeeze the barrel of the rifle between his arm and his left side and trapped it. The NVA yanked his rifle free, slicing Roy on the side. Before he could strike again, Roy wrestled him to the ground and thrust his knife deep into the man’s side. Yanking it out, he drove the knife down a second time into the man’s chest. At last the soldier was still.

Staggering to his feet and visibly shaking, Roy turned to face O’Connor. “I’m okay,” he shouted.

O’Connor lowered his AK-47 and yelled back, “My interpreter is still alive–make sure they get him!”

Roy leaned down and tried to retrieve his knife from the NVA’s chest, but it would not come free.

—Legend, p. 216. See also pages 193 – 215

The Recon knife had no saw teeth. Apart from being loosely Bowie style, the CSO-issued knife had little in common with the JPSK. Both had leather washer handles, but the turned-down grip of the Recon was burnished smooth, like the US Navy “shark” knife, while the grip of the JPSK had deep, visible grooves like a Ka-Bar to help you hold on to it when it came to a sudden stop (on a tent stake, or against a head, or in some ribs).

An Army helicopter pilot might have to plunk her or his bird down in the middle of a firefight, but the JPSK was originally intended for jet pilots, fast movers who range farther over enemy territory. For most of our opponents during the Cold War, capturing a pilot provided a valuable resource for intelligence, propaganda, and negotiation purposes. An aviator would have a better chance of getting home to his family if he got captured than if he fought to avoid capture, miles from help and surrounded by enemies.

As with every rule, there have been exceptions.

*****

Aircrews Fighting Outside the Cockpit

There was a poem recited by many a pilot shot down in Southeast Asia:

Jolly Green, Jolly Green

Prettiest sight I ever seen

In the summer of ’82, a few of my USAF Academy classmates and I spent three weeks at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, visiting various portions of the A-10 base there. No way to get an incentive ride in a single-seat Warthog, but we did fly in the Jollys of the local rescue squadron.

One of the PJs (USAF pararescue jumpers) I spoke with at Myrtle Beach had served in Southeast Asia. He said that our pilots would go places the devil himself wouldn’t go “in their mach 2 office” (the F-4, for example, could fly at mach 2.23, more than twice the speed of sound). But when they got shot down and, in his words, started “getting hunted like an animal,” many felt out of their element. Here are a few cases where aircrews had to fight back on the ground, the old-fashioned way: face-to-face.

Rodney Allen Knutson was shot down in an F-4B over North Vietnam on 17 October 1965, and actually used his .38 revolver (a USN issued Smith and Wesson Victory Model) to shoot an NVA regular who shot at him with a rifle as he tried to surrender. Navy pilots carried tracers in their .38s. Knutson told us he wondered if he was violating the Geneva Conventions when he returned fire with the tracers in his revolver at the first NVA who was trying to kill him. Another NVA snuck up behind Knutson. The downed aviator shot over his shoulder at the second NVA. Already injured during ejection, Knutson was knocked out my muzzle-blast from 7.62x39mm at point-blank range–the bullet grazed his nose–and he woke up in captivity. But he had killed both NVAs. Knutson survived captivity, but for his trouble he was one of the first American POWs introduced to the North Vietnamese “rope treatment.”

Lt (jg) Frank Pendergast, an RA-5C backseater who got shot down over the surf off a North Vietnamese beach, expended all the tracers in his .38 into the sky for their intended purpose, signaling his location to an approaching rescue helicopter (these days operators use IR lasers pointed into the sky to designate their location), before he got captured in waist-deep water offshore. The NVAs took his revolver away. When an NVA pointed the US Navy issue revolver back at Pendergast at point-blank range and pulled the trigger, the junior-grade lieutenant did NOT stab back with a JPSK. He pulled a backup pistol–a diminutive Colt .25 ACP–from a flight-suit pocket and shot the NVA in the face. He then knocked down his other guard, tossed the guard’s AK in the water, broke away, and ran to the chopper. The second NVA fished his AK out of the surf and chased him. Pendergast turned and exchanged fire with the NVA. Any distance farther than across a dinner table is probably beyond the effective range of those little pocket pistols, but the helicopter’s door gunner covered Pendergast’s flight to the chopper. Thanks to that brave rescue crew, and his backup pistol, Pendergast was free, and back on his carrier that evening.

Red Air Force navigator Ira Kasherina and engineer Sonya Azerkova had to escape and evade (E&E) when their PO-2 wouldn’t fly and their airfield got overrun by nazis in WWII.

The lady aircrew wound up having to use their issued Tokarev TT-33 pistols to shoot their way out of being raped by German soldiers (Bruce Miles, Night Witches: The Untold Story of Soviet Women in Combat, pp. 174 – 180).

But I don’t recall ever meeting, hearing, or reading about a Nam-era pilot who used his JPSK to silence an enemy. Several accounts tell of downed pilots using their JPSKs for survival tasks.

The JPSK, and knockoffs of the JPSK (most made in Japan), were also popular among ground troops in Southeast Asia, judging by several photos from the era showing the distinctive leather washer handle and hexagonal pommel of the JPSK on the gear of various soldiers and support personnel. One’s utility / survival knife is a highly personal item, and the farther one got out into the bush, the less officers cared (if they had ever cared at all during the war) about standardizing such equipment. Standardization of, say, rifle cartridges is important to the war effort. Utility and fighting knives, not so much.

One can almost hear a conversation between a Navy pilot and his former Annapolis roommate in the USMC infantry. Over a Schlitz or whatever, one starts to admire the other’s blade. The admired gripes that he doesn’t like thus-and-such aspect of his own (blade too long, blade too short, balance too far back, or whatever). He then says he would prefer one like the other has. And thus a swap, a significant portion of the way logistics really happen in the military, takes place.

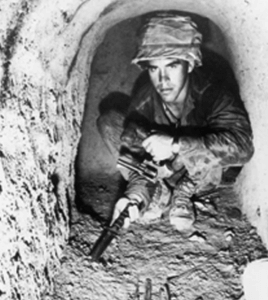

‘Nam GIs used knives and sticks to probe for mines and other booby-traps.

When I went through US Army RECONDO in 1983, SFC Gogurt (we called him “Yogurt,” but never to his face), wore a 5th Special Forces patch on his right shoulder sleeve.

In the Army, if one has served in combat, they may wear the patch of the unit they served in at the time on their right shoulder. The left is reserved for one’s current unit–in Gogurt’s case at the time, the diamond-shaped patch with four ivy leaves (“ivy” being a pun for the Roman numeral IV) of the 4th Infantry Division (mechanized).

Gogurt told me that in Vietnam, on those rare occasions they could pin Charlie to a fight, the VC and NVAs KNEW we had superior artillery and air support, “so they got REAL CLOSE so we couldn’t use it on them.” He added, “That wasn’t any fun at all.”

Early in the war, the NVA and Vietcong learned that the safest place during an air strike was as close as they could get to the American position.

–Eric Blehm, Legend, p. 214

Given the sheer numbers of GIs in ‘Nam and the number of times our remote fire bases got overrun (or at least partially overrun), as well as the then-new M-16’s well documented tendency to go “click” instead of “Bang!” when a Charlie decided to share one’s foxhole or trench, it seems likely that at least one if not several JPSKs or JPSK knock-offs wound up in somebody else’s chest. But I have yet to find a documented account of such an occasion that lists the specific brand of knife as a JPSK.

I was an enlisted Cadet Candidate, and then a Cadet, at the Air Force Academy in the early 1980s. During the Reagan administration, the Cold War wave reached the shallows and began to crest. USAFA cadets were almost all slated to fly. When we went through USAF SERE training, the projected math was that 3 days into the next European war, half of our aircrews would be downed on the other side of the lines. Unlike my father’s generation of pilots in Southeast Asia, we could NOT expect timely helicopter rescue. The Soviets and their allies specialized in air defense. A chopper wouldn’t have much chance beyond the FEBA, forward edge of the battle area.

We were advised to hole-up by day, and move at night. We were to avoid contact with anyone at nearly all costs. But if we had to seek help from a local behind enemy lines, say because we were dying of injury or starvation, we were given several criteria:

- The person we approach should be male. Females might empathize, but do not have as much agency as males in most societies, all the more so back then. That logic might be exactly opposite what a female pilot might need to do, should she be downed, but that was not considered in the American military of 1982.

- We should try to find an older person. In the early 1980s, there were still people around who remembered that we had been on the side of the good guys in World War Two. An older person might be more empathetic than a child who had grown up under the communist propaganda machine. Older people also tend to be wealthier and have more of a say in the local doin’s.

- “Lastly, and most importantly,” the instructor said, “you should approach someone who is alone. In a group, individuals might want to help, but would likely be afraid of getting turned in. Also, if he doesn’t have any friends within earshot, it will be easier to . . .” the instructor paused for only half a beat, before continuing, “. . . eliminate the threat to your security, should he rebuff your advances.”

The students sitting in the audience exchanged glances with one another. “Is he talking about what I think he’s talking about?” one whispered. I nodded. Looking back, I don’t know why we were so shocked. After all, before getting shot down, we would probably be killing people in droves with napalm or cluster bombs.

The Air Force Academy upperclassman I respected most was Michael J. Wermuth, Class of ’83. Wermuth had been an enlisted US Army soldier who went to West Point’s prep school before receiving an appointment to USAFA. Wermuth told me that Air Force pilots “don’t have to look a man in the eye when they kill him.”

I’m glad I never had to choose between the life of a stranger trying to stay out of hot water with communist occupiers and my own freedom. If I had, a JPSK might’ve raised less of a ruckus than a pistol shot.

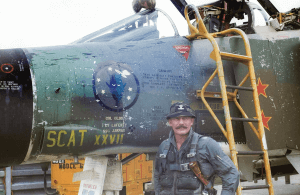

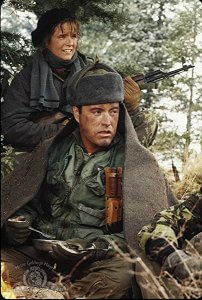

In the mid-1980s movie Red Dawn, Powers Boothe played a downed American F-15 pilot. The JPSK was such an iconic piece of aviator survival gear, the Red Dawn costumers made certain to include one on his vest.

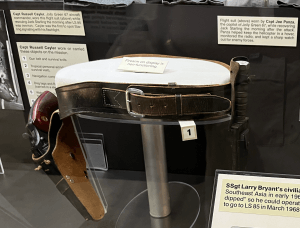

By the 1980s, a squared-off sheath with a black metal (sheet steel? aluminum?) end cap had replaced the original pointed leather sheath.

Here’s what the sheaths look like from the other side.

*****

My JPSKs

I started collecting knives long before I was old enough (or had enough money) to collect firearms. In those days (the 1970s), a bayonet from the early 1900s, or even the late 1800s, could be had from a military surplus store (when surplus stores actually sold surplus) for $10 or $15. Just to keep it in perspective, gas was a buck a gallon, and you could take your honey to McDonalds for less than $5 back then.

Holding a butt-heavy JPSK never gave me the same magical feeling Luke must’ve felt when he first switched on his father’s light saber, which is perhaps ironic, since my dad was a pilot like Darth, and a JPSK was probably his blade.

But there were certain staples I felt belonged in any serious military knife collector’s collection, including

- The Ka-Bar

- The JPSK

- The US Navy “shark” (or deck) knife

- Some version of the Fairbairn-Sykes commando dagger, perhaps its cousin the USMC Raider’s stiletto

Commercially available Gerbers, similar to the one pictured below, had also been carried in Vietnam.

My ‘Nam-era unicorn was (and still is) a Randall. Custom-built Randalls had been carried by those serious about edged weapons in Southeast Asia. Some Randalls got their inspiration from the MACV-SOG Recon.

I bought my first JPSK from a surplus store or a garage sale when I was a teenager. The stacked leather washers of the handle, and the sheath, were of a light orange, almost yellow tan. I named it Karen Lynn, after my first girlfriend, whose flaxen hair nearly matched the leather. The blade and pommel were parkerized a dull light grey.

Can’t remember now whom I gave Karen Lynn to when I went back on active duty in 1986. I was moving and needed to lighten the load, but I would never have sold it at a garage sale. Weapons have special significance to warriors, and bestowing a weapon upon a friend is the only way to properly dispose of one. It is an act signifying special faith and confidence that they will handle it wisely and well.

The 5″ bladed JPSK remained an issued item, in more or less its original configuration, well into the following century. Although I wound up as an aircrew member on C-130s in the 1990s, I was never issued a JPSK. They gave us “switchblade” folding knives with a rescue hook for cutting parachute cord and seat belts, instead.

A few years ago I bought my second personally owned JPSK, the black-handled one pictured above, for about 8 times what I paid for the first.

My second JPSK was from the ‘Nam era. The end of the hexagonal pommel still has some light colored paint visible. Manufacturing data was stamped on the left flat of the pommel. The letters are right-side up when the blade tip is down. That one says

Or, if you find that hard to read,

CAMILLUS

N.Y.

1 – 1967

The last line of numbers, designating manufacture of the JPSK (or at least its pommel) in or about January of ’67, are offset slightly left of center to make room for the 10, 11 and 12 of October, November and December when they came around.

My third and final JPSK isn’t nearly in as good shape as the ‘Nam era one. SERE students used and abused it ’til it was declared non-serviceable and surplussed. The washer handle was split by the thin but strong inner strands of paracord (“550,” or parachute cord), I assume when it was lashed to a stick. The blade has been used as a pry-bar till it literally bent at a (very slight) angle from the tang / grip.

But JPSK #3 is far more precious to me. It was a gift from an old and dear friend who was a SERE instructor. It probably accompanied many a SERE student, or SERE instructor candidate, or both, through much fatigue, cold, and privation. Most of the parkerized finish has been worn off the blade by the many young men and women who sharpened it on the tiny stone that came in the sheath. If only that JPSK could tell the story of each and every blemish and scar . . .

That JPSK is post Cold War. It’s a GWOT (Global War on Terror)-era piece of military hardware. Stamped on the lower right flat of the hexagonal pommel (again, with letters and numbers oriented to be read with the blade tip down) is:

. . . meaning its parts were made in March of 2011, though possibly assembled a month or two later. OKC, the Ontario Knife Company, started turning out knives in a water-powered mill in 1889. They are still a supplier of US military knives.

There are some interesting differences between my ‘Nam-era Camillus JPSK and the GWOT-era Ontario. The fuller is wider, deeper, and trapezoidal on the Camillus. The fuller of the Ontario is longer but narrower, shallower, and symmetrical.

The sides of the Camillus blade are rounded; the various surfaces of the Ontario blade are flat, with sharply delineated edges.

The grip or handle of the later (Ontario) JPSKs are actually slightly longer, by about half the width of the octagonal portion of the pommel.

I’ve since passed the Camillus JPSK on to a friend who used to serve in the USAF Security Police, and as an officer on the Ft Worth PD. He mentors Civil Air Patrol cadets and has an appreciation of the JPSK’s history. The only JPSK left in my collection the one made by OKC.

*****

But is it Art?

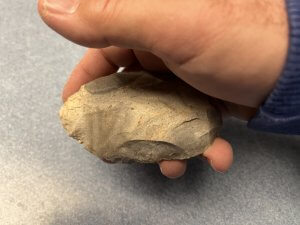

The ability to make and use tools is what brought humans out of caves, and has brought us near to extinction on a few occasions. Another thing that separates us from most animals is art. Humans have made many great works of art through the ages. Some of the most beautiful and enduring works of art are tools, including weapons.

Some (most of whom are not likely readers of this website) may scoff at the notion of weapons as art. In their eyes, nothing designed for taking life can be beautiful. A master automobile craftsman may be forgiven for preferring one brand of tools over another, but is not likely to hang a Snap-on wrench on her or his wall to look at when the long workday, and all the days of work, are done.

And yet, museum tours reveal that throughout history, some weapons have been forged or flaked by master craftsmen who appreciated them as works of art, as well as functional tools. Anyone who is a warrior at heart has an appreciation for well-made weapons.

Don’t Say that Word!

The NRA and the USCCA would prefer that we strike the word “weapon” from our lexicon, because it has negative connotations. They (and their lawyers) would prefer that we use terms like “firearm” or “cutting tool” to win battles of words against the hoplophobes, who are masters of Orwellian word-twisting.

But I feel avoiding the word “weapon” when referring to items clearly designed for combat is disingenuous. I for one am not ashamed to call weapons weapons, in the interests of clarity and truth. I will own that they are purpose-built to be dangerous. As Jeff Cooper would say, “they would be of little use otherwise.”

Although the JPSK was designed as a survival knife, survival might involve fighting, so that makes it a weapon. JPSKs have almost certainly been used as weapons, at some time or other, whether or not I personally have found accounts that will testify to that almost inevitable fact.

I think Glocks are downright ugly, but the Glock was my go-to duty pistol through much of a long and occasionally terrifying law enforcement career. A Glock is my go-to off-duty companion to this day.

As a child of the ’60s & ’70s, who grew up loving the Blues and Soul of the Motown sound, I at first did not consider Rap an art form. I have since decided Rap is an art form; but I’m still not entirely convinced it’s music.

I never thought of the JPSK as lovely, though I’m sure those who actually needed one hold it in high esteem. I’m coming around to the idea that it may also be a work of art.

–George H, former aircrewman, who barely survived survival school

*****

*Possibly an La-9 or La-11, though it was ID’ed as a La-7, and sometimes as a Yak-11. According to one source, the North Koreans & Chinese never had La-7s. The M4 bayonet in that photo was on display in the Korean War exhibit at the National Museum of the Air Force.

Leave a Reply